Empedocles of Akragas (c. 495–435 bce) is famed as the first presocratic to give us a four-element theory of earth, water, air and fire and for his conception of a cosmic cycle. His work presents no small difficulty though. The problem is that some fragments seem to give us a naturalist account of the cosmos, its origins and fate along with the origins of life, with some interesting innovations but very much in the periphusis tradition. On the other hand, some fragments talk of the transmigration of the soul, of magic, of purification of the soul, of bringing back from Hades the strength of a man who has died, of Empedocles himself as some form of god among men and as some form of divine prophet.

One solution, emanating from Diels, is to suppose that Empedocles wrote two poems, one On Nature, the other On Purifications and to allot the ‘scientific’ fragments to the first poem and the ‘religious’ ones to the second. One might then date On Purifications as later or earlier than On Nature, with Empedocles developing his thought between the two.1 This is now seen as seriously outdated and relying on a nineteenth-century historiography of an antithesis between science and religion.2 Editors have also failed to agree how to distribute the fragments between the supposed two poems.3 This can be used as a strategy for elision as well. Assuming two poems, we privilege the On Nature poem. On Purifications can then be thought of as an earlier work, with Empedocles progressing from a religious/magical view to a more scientific one, or On Purifications can be seen as a later work, with Empedocles declining in old age. In either case we privilege On Nature and marginalise or ignore the religious/magical evidence of On Purifications.

With the discovery of the Strasbourg papyrus, which gives us some new material on Empedocles, and the breakdown of the ‘conflict’ historiography of science and religion any boundary between the two supposed poems has become further blurred. Inwood now doubts that there were ever two separate poems and indeed the evidence in favour of two poems is remarkably thin,4 though Primaversi finds new ancient evidence for two poems of differing sizes.5

As far as this chapter is concerned, I am not worried whether there were one or two poems. Even if there were two, we have no a priori grounds for treating them in a different manner, as representing different phases of Empedocles’ thought or being written for two different audiences. We have to deal with the fragments on an even footing and we have no grounds for, e.g. placing all the fragments compatible with a naturalistic interpretation in one poem, all the rest in another and then having some explanation why the rest do not represent the true thought of Empedocles.

Empedocles wrote in hexameter poetry, which does not make the task of interpreting him easier. Even in the ancient world, there was a dispute about the nature of Empedocles’ poetry. Plutarch tells us that:

It is not Empedocles’ habit to adorn his topic with vacuous descriptions, akin to some bright flowers, to create a beautiful style, but rather he gives a precise illustration of all substances and powers.6

Aristotle, on the other hand, is rather more disparaging:

Homer and Empedocles have nothing in common except metre, so while it would be just to call the former a poet, we should rather call the latter a physical philosopher.7

One issue in Empedocles will be how much licence we have to see references to gods etc. as poetic representations which can be given a naturalistic interpretation.

Empedocles’ ontology

It is possible to make a case for Empedocles being a naturalist. Let us begin with his ontology. To a certain extent, Empedocles agrees with Parmenides in that there can be no generation from nothing. So Empedocles says that:

There is no birth of mortal things, nor do any end in some unhappy death, but there is only mixing and interchange of the mixed, birth being the name given to these things by men.8

He also says that:

It is not possible for something to be generated from the non-existent and that something which exists should be destroyed cannot be accomplished and is utterly unheard of.9

Pseudo-Plutarch also tells us that:

Empedocles affirms that nature is nothing else but the mixture and separation of the elements.10

This then looks like standard periphusis tradition material. There are some basic entities which do not come into or go out of existence and what we understand as change is the mixture and separation of these basic entities. Empedocles Fr. 135 is also interesting in that it says:

This law for all extends through wide ruling air and through the boundless light of the sun.11

This is generally taken to refer to the prohibition on eating meat or beans. However, it is expressed in a physical manner and we might take it to be an expression of universal physical law instead.12

Empedocles and meteorology

As presocratic meteorology has been a major theme for this book, we ought to look at what Empedocles has to say. Aristotle in his Meteorologica informs us that:

Some say that in the clouds there is fire. Empedocles says this is the sun’s rays trapped in the clouds … Lightning is this fire flashing through the clouds, thunder the noise of it being quenched.13

So some novelty in that the sun’s rays are involved in the explanation of lightning and thunder but we do have a natural explanation and no sense of any of this being caused by the gods. Seneca in his Natural Questions, discussing hot springs says that:

Empedocles says that there is fire in many places which the earth covers and which heat the water.14

Empedocles himself says that:

Iris brings from the sea a wind or great rainstorm.15

So the rainbow (or the phenomena associated with the term Iris) is associated with bad weather. There is no explanation for the rainbow here but no sense it is a portent sent from the gods either. Given that we have a good number of fragments from Empedocles, lots of testimonia and that Pseudo-Plutarch and Stobaeus reference Empedocles a lot, this is actually not very much on meteorology compared to other presocratic thinkers. However, the explanations are natural with no sense of these being caused by the gods,

Empedocles’ cosmogony

The details of Empedocles’ cosmic cycle have been much debated and there have been several different ways to think about how the cycle may work. I am going to offer my own view here but not defend it in any depth or detail. I hold the orthodox or symmetrical view (so called because it sees the roles of love and strife as symmetrical) with a few minor variations.16 What I want to show here is that it is possible to have a view of Empedocles’ cosmic cycle where there are only natural entities and processes.

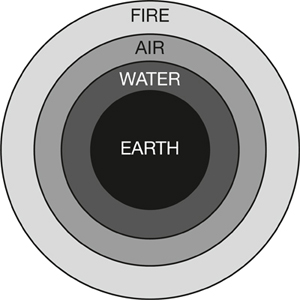

Empedocles’ cosmic cycle can be broken up into four phases, though it ought to be emphasised that Empedocles does not make these divisions. As the process is cyclical, the numbering of the phases, and the point at which one starts is entirely arbitrary. The key processes are that love associates the four Empedoclean elements of earth, water, air and fire into a homogeneous mixture, and then strife dissociates the elements into four separate groups. So the four phases are:

1)The complete domination of strife, where the four elements are entirely dissociated and there is no mixing.

2)Increase in the influence of love, such that the elements become increasingly mixed with one another.

3)The complete domination of love, such that there is a perfect mixing of the elements.

4)Increase of the influence of strife, such that the elements become increasingly dissociated from each other.

There is cosmogony and zoogony under the increasing influence of love, working by association of the elements. However there is also a destruction of the cosmos and living things as love nears complete domination. Similarly, there is cosmogony and zoogony under the increasing influence of strife, working by dissociation of the elements. Again there is a destruction of the cosmos and living things as strife nears complete domination. When love is completely dominant there is rest. It is not clear how long this lasts for,17 but at least long enough for Aristotle to complain about the conceptual difficulties involved in restarting motion in the universe from a state of total rest.18 When strife is completely dominant there is maximum motion, although it is unclear what that might amount to. This is momentary and love begins to increase its influence directly after the high point of strife.19 Technically this gives us only three phases as the dominance of strife is only momentary, but it has traditionally been counted as a phase in the orthodox interpretation. This, or something close to it, is shared by those who opt for the orthodox or symmetrical view of Empedocles’ cosmic cycle. All that is required here are the four Empedoclean elements and the two principles of Love and Strife. So this can all be understood in an entirely naturalist manner.

My own view of Empedocles’ cycle emphasises the role of chance in cosmogony for Empedocles and the differences between successive cycles rather more than other accounts. Some interpretations have the distribution of the elements at total strife like this:

An alternative view is that total strife is more like a 1960s lava lamp, where one might have the four Empedoclean elements represented by four different coloured immiscible liquids. At total strife, each liquid is in one drop and not many, but the drops may have all sorts of shapes and distributions, the above diagram being merely one possibility. If the above diagram happened every time, then the next phase of the cycle might be identical every time. With the lava lamp model, it may be radically different each time.

Total love does give us the same thing each time, but there is a question of how determinate the cosmology is. Aristotle tells us that:

Empedocles says that air is not always separated out upwards20 but according to chance – he says in his cosmogony ‘Thus at one time it ran by chance, but many times it was otherwise’ – and he says that the parts of animals are for the most part generated by chance.21

If this evidence is reliable, it is of considerable significance because the separation of air is absolutely fundamental to Empedocles’ cosmogony.22 So I agree with Trepanier who says that:

Empedocles’ cosmic cycle did not consist of a completely identical pattern of recurring events, as in the later Stoic doctrine of the cosmic cycle.23

The lack of teleology and the strong role for chance in Empedocles’ cosmogony militate against any divine intervention in the cycle. It also allows us to understand why the cycle repeats. With a strong role for chance and different contents for each cycle, there need to be repeats in order that we eventually get a world like ours. Empedocles does diachronically what the atomists do synchronically with multiple cosmoi.

Empedocles’ zoogony

Empedocles is famous, perhaps even notorious for his explanation of the origins of life. There are several stages to Empedocles’ zoogony, beginning with the generation of body parts. We then get their chance association and ultimately the formation of creatures which are viable in themselves and are able to reproduce. At the first stage:

Earth came together by chance with these in roughly equal quantities, Hephaestus, rain and shining air, anchored in the perfect harbours of Kupris, either a little more or in more of them. From these were generated blood and the types of flesh.24

And kindly earth received in its broad melting-pots two parts of the glitter of Nestis out of eight, and four of Hephaestus; and they became white bones, marvellously joined by the gluing of Harmonia.25

Hephaestus in the first passage is generally taken as a poetic expression for fire, so we have the four Empedoclean elements of earth, water, air and fire coming together to form blood and flesh. Kupris is symbolic of love. In the second passage, Hephaestus is again fire while the ‘glitter of Nestis’ is taken to be water and air. Once we take the poetic names away, we have earth, water, air and fire coming together by chance in certain proportions to make blood, flesh and bone.26 Here one would reasonably suppose that there were many other occasions where these ingredients came together, but not in the right proportions, and so blood, flesh and bones were not formed. Pseudo-Plutarch gives us an overview of the generation of life for Empedocles:

Empedocles believed that the first generation of animals and plants were not generated complete in all parts, but consisted of parts not joined together, the second of parts joined together as in a dream, the third of wholes, while the fourth no longer came from homogenous substances like earth and water, but by mingling with each other.27

So at the next stage we then have the dream (nightmare?) scenario of:

On the earth there burst forth many faces without necks, arms wandered bare bereft of shoulders, and eyes wandered needing foreheads.28

Many sprang up two faced and two breasted, man faced ox progeny, and conversely ox headed man progeny.29

These things fell together, encountering each other by chance, and many other things were constantly being produced.30

So the parts of bodies join up in an accidental fashion and there is no mention of any part being played by any other agency. Aristotle then says:

Whenever everything happened as if it were generated for the sake of something, then they survived, having come together accidentally in a suitable manner. Where this did not occur, however, they perished and are still perishing, as Empedocles says concerning his ‘Man faced ox progeny’.31

Ultimately the result of this process are species which are capable of having viable offspring. The process in itself can be seen as an entirely natural one. The elements come together by chance to form body parts, they come together by chance to form viable species.

Love and Strife

Sometimes Love and Strife are referred to as forces.32 I have very strong reservations about this and would much prefer to call them principles of association and dissociation. Love and Strife are entities on their own rather than properties of matter. They do not generate attractive or repulsive forces between matter, they just effect association or dissociation. Contrary to what we understand as forces, their effect varies over time. Their effect also discriminates between different types of matter.33 It is better to refer to love and strife as principles of association and dissociation respectively. This is not to single out Empedocles, as I have reservations about using the word force in this sense in relation to any of the presocratics. As we will see with Leucippus and Democritus, I also object to calling the like to like effect a force. It is not, it is a sorting principle which operates only when the correct type of motion (vortex motion) is happening.

I take the view that there is no teleology in Empedocles. I have argued this in some detail elsewhere, so will just note the main points here.34 One might question whether there is an end state for Empedocles at all, given the cyclical nature of his cosmology. If there is to be an end state, it is difficult to see just one on the symmetric model. Total association and total dissociation are the effects of Love and Strife so would be the main candidates but that gives two end states. A cosmos is both generated and destroyed by both Love and Strife so could hardly be an end state but that looks odd in relation to Greek teleology generally. Teleology is generally associated with intelligence and the good but that looks odd when Love and Strife destroy the cosmoi they create.35 Some passages appear to indicate teleology in relation to the generation of the eye,36 but one can commonly find even modern biologists and biology texts employing explanations which look as if they imply intelligent design when no such implication is intended. One might quite easily say, when explaining the function of the eye, that ‘the eye is designed such that …’ while remaining a staunch evolutionist.

If that is so, cosmology for Empedocles is the action of the two principles of Love and Strife on the Empedoclean elements and that looks to be entirely natural for both entities and processes. I recognise that there are many other viable views of Empedocles but these are not problematic for the naturalist view. If there is teleology for instance, that is unlikely to be problematic given what we have seen with the Milesians. There are other views about the succession of phases in the cycle but again these do not make any part if the cycle non-natural. There are though significant similarities between how Love and Strife work and the idea of sympathetic interaction. As Kingsley has pointed out:

These forces of love or attraction and strife or repulsion are the fundamental governing principles of magical operations both in the ancient Greek world and elsewhere.37

Sympathies may be part of the magical view, but that does not make them of necessity anything non-natural. To quote Plotinus again:

How is there magic? By sympathy, and that naturally there is a sympathy between like things and an antipathy between unlike things.38

Aristotle certainly saw Love and Strife as natural agents:

Strife is no more the reason for destruction than it is for being. Similarly, nor is love in relation to being. For drawing everything into one it destroys everything else. At the same time he gives no account of the reason for change, except that it is natural – ‘When great strife had grown strong in the limbs, and sprang to its realm as the time came, which was appointed for them in turn by a broad oath’ – as if change were necessary. But he gives no reason for this necessity.39

One can then build a strong case for Empedocles employing only natural explanations if we restrict ourselves to a certain set of fragments.

Empedocles does talk about gods in the context of the cosmic cycle, these gods seeming to be long lasting rather than immortal. As Trepanier has pointed out, long life rather than immortality is adequate for a god in Empedocles. If there are no immortal entities, this lessens the tension between the theology and the physics.40 Material from the Strasbourg papyrus tells us that:

But in Love we come together to form a single ordered whole.

Whereas in Hatred, in turn, it grew apart, so as to be many out of one,

From which come all beings that were, all that are, and all that will be hereafter:

Trees sprang up, and men and women,

And beasts, and birds, and fish nurtured in water, and even long-lived gods, unrivalled in their prerogatives.41

We get something similar in Simplicius:

In anger they have different forms and are all apart,

But in Love they come together and are desired by one another,

For from these come all beings that were, all that are, and all that will be hereafter:

Trees sprang up, and men and women,

And beasts, and birds, and fish nurtured in water, and even long-lived gods, unrivalled in their prerogatives.42

One strategy here is to look for ways in which something which Empedocles would recognise as a god could come about through the physical processes described here, such that we have natural, long-lived but not immortal gods.43 Primaversi has argued that the sphere which results when Love is completely ascendant is referred to as a god by Empedocles.44 Primaversi has also argued that, at the other end of the cosmic cycle, while the elements are immortal, the four pure groups they form when Strife is completely ascendant are long-lived but mortal and can be considered in some sense as gods.45 Empedocles’ mythology mirrors the cosmic cycle and can be explained in terms of it,46 in a similar way to that in which Homer’s gods were taken to represent physical entities.47 So in Fr. 115, when a god is expelled from the companionship of the other gods for trusting in Strife, this mirrors the break up of the Sphere by Strife as the complete domination of Love ends.

With the mirroring analogy, it is notable that the view pursued is that the theology mirrors the physics and that we can explain the theology in terms of the physics, so gods are really elements, etc. However, the mirroring analogy could be taken in reverse, such that the physics mirrors the theology and the elements are really gods. Again, this mirroring can be thought of in terms of privilege and elision. If the theology mirrors the physics, the physics is primary and to some extent we have managed to marginalise or downplay the theological aspects of Empedocles’ thought. Reverse that, and say the physics mirrors the theology and we might have a radically different picture of Empedocles. This is not to advocate such a view, merely to raise its possibility and to question why we privilege the first model over the second. One might try to do that in terms of similarity to ancient interpretations of Homer, or perhaps out of historical generosity to Empedocles. So we try the mythology mirrors the physics line first. If that cannot be made to work, though, the second line might be worth thinking about.

Empedocles’ magic?

There are some difficulties for a naturalistic reading of On Nature in that the final fragment, Empedocles Fr. 111, says that:

All the remedies (pharmaka) which exist as a defence against evils and old age

You will learn, as for you alone will I accomplish all these things

You will stop the might of tireless winds which over the earth

Sweep and destroy fields with their gusts

Then again, if you wish, you will bring on the requiting winds

You will make, from a black rainstorm seasonal drought

for men, and out of a summer drought you will generate

Tree nourishing streams that dwell in the aether

and you will bring back from Hades the strength of a man who has died.48

In the first line we have pharmaka. pharmaka is best rendered ‘remedies’ rather than potions as it leaves open the possibility that different types of therapy are involved here, as LSJ give as a possibility for pharmakon ‘enchanted potion, philtre: hence, charm, spell’.49 Weather working was seen as part of magic, and was sometimes attacked as such, as we saw with On the Sacred Disease and the comments on ‘If a human by magic and sacrifice can bring down the moon, eclipse the sun, make storm and good weather.’50 The final line appears to assert the existence of Hades and the possibility of necromancy. On why this knowledge is ‘for you alone’, Kingsley argues that the relationship of mage and apprentice has traditionally been a secretive one with the knowledge of magic privileged between them.51

There are a number of strategies one might try to argue that this passage is naturalistic. Diels’ view is that this passage promises nothing more than modern science does, the content of the laws of nature such that nature can be controlled.52 Even if we take pharmaka simply as medical remedies, this looks rather strange though. It is difficult to see how science will give a single person the ability to control the winds or to create rainstorm and drought. There are also considerable magical resonances here.

One might then try to think of this in terms of a natural magic.53 Betegh, talking about a passage in the Derveni papyrus, comments that:

The obvious parallel here is Empedocles, and especially his promise at B111 to impart knowledge of controlling nature in an extraordinary, but not supernatural way.54

On this approach, we treat pharmaka simply as medical remedies or natural magic remedies. We take the view that ‘to you alone’ is poetic emphasis, as it would be odd to advertise privileged knowledge in a poem. The weather working we take as natural magic based on an enhanced knowledge of the elements and Love and Strife. The difficulty though is the final sentence. Bringing back the strength of a dead man from Hades can hardly be construed as natural magic. Whether that is done by a spell or invocation from here or whether in involves some form of spiritual or physical travel to Hades,55 I do not see how this can be done naturally, if we take the last line literally. If the final line was a single line fragment on its own, one might attempt to read it as something to do with metempsychosis, the cycle of reincarnations being hell. The context of the claims leading up to the final line are very much against such a reading though. One might try a reading along the lines that we are already in hell in our ordinary lives, and the fragment is about education and being lifted out of that hell. The fragment offers to do that for you and you in turn will be able to do that for other people.

Alternatively, one might read the final line as an allusion to resuscitation or aiding recovery from some near-death experience where someone’s life force might be thought, poetically, to have departed for Hades. So there need be no commitment to Hades existing or our travelling there or summoning souls in the manner of Odysseus in Odyssey XI. In favour of that view one might argue that this fragment begins with something medical and now ends with something medical and that matches the cyclical patterns and themes that can be found elsewhere in Empedocles’ poetry. Also in favour of this reading is that Empedocles is supposed to have written extensively on medicine, although those works are now lost.56 What one might also argue in terms of setting is that Empedocles gives us a strongly natural account of cosmogony, zoogony and the cosmological cycle in general. That then gives us a licence to interpret this passage in natural terms if it is possible to do so. Curd comments that:

In B111 Empedocles holds forth the promise of remarkable and seemingly supernatural skills, yet embeds this promise in the naturalistic account of the roots of all things, of the forces that combine and separate these roots and the consequent formation of the kosmos and living things.57

There are some other less effective strategies here. We could move this fragment from On Nature to On Purifications and employ some strategy to lessen its effect. It is difficult though to see how ‘and you will bring back from Hades the strength of a man who has died’ fits as a mirror to any part of the cosmic cycle. There is also an issue of justification and pre-judging the sort of Empedocles we want. Wright has Fr. 111 as the last fragment of On Nature,58 Inwood has Fr. 111 as his fifteenth passage so there is no consensus to move the passage away.59 Kingsley argues that Fr. 111 should be close to the beginning.60 The attempt by van Groningen to excise the passage on the grounds that there is nothing comparable elsewhere in Empedocles is unconvincing.61

I will reiterate a point I made in the chapter on Plato and Aristotle. It is perfectly possible to be interested in philosophy and magic or natural science and magic. It is perfectly possible to theorise and philosophise about the nature of magic. The basis for magical disciplines is there in Aristotle and Plato and there are many examples of how that was developed in later antiquity and in the Renaissance. Just as the historiography of permanent antithesis between science and religion has broken down and had consequences for Empedocles scholarship, so has the historiography of permanent antithesis between science and magic. A further issue here is whether Empedocles was a philosopher with an interest in magic or whether magic formed a fundamental part of his thinking.62 It should be clear that with Renaissance thinkers such as Kepler and Harvey,63 aspects of magic were fundamental to their thinking and indeed to the revolutionary theories they put forward in astronomy and anatomy. We cannot immediately dismiss the idea that Empedocles had magic as a fundamental part of his thinking.

Empedocles as a shaman?

Dodds claims that:

Empedocles represents not a new but a very old type of personality, the shaman who combines the still undifferentiated functions of magician and naturalist, poet and philosopher, preacher, healer and public counsellor.64

The last line of Fr. 111, ‘you will bring back from Hades the strength of a man who has died’ has led some commentators to compare Empedocles to a shaman.65 However, I would disagree with Kingsley who comments that:

There can be no possible justification for avoiding the literal meaning of this remarkable statement or trying to interpret it away allegorically.66

It is one possibility to take this line literally, but given that Empedocles wrote in poetry and other parts of his poem are clearly allegorical, we can at least consider other ways to interpret this line as I have above. Certainly, communing with the spirits of the dead is one thing that shamans are supposed to do. However, one similarity does not make an identity and there are differences between what we know about shamen and what we know about Empedocles. One might add though the usual conception of a shaman includes the ideas of divination and healing and we get these in Fr. 112. There is no sense here though that Empedocles believed in the need to enter into some state of altered consciousness in order to commune with the dead, if that indeed is what is meant by this line. As with Pythagoras, it is one thing to say that they share some of the traits of a shaman, another thing to say that someone was a shaman.

Empedocles’ claims

Empedocles Fr. 112 may also make some claims which are problematic for a naturalistic reading. Guthrie comments that in fragment 112:

The same arrogance and claims to supernatural powers appear in his promise to Pausanias in his poem on nature (fr. 111).67

Indeed it is hard to construe Fr. 112 in an entirely naturalist manner:

O Friends, who live in the great city of the yellow Acragas,

in the highest part of the city, caring for good deeds,

I greet you. I am a divine god to you (humin), no longer mortal

I go around honoured by all, as is fitting

crowned with ribbons and festive garlands

I am revered by all I come upon as I arrive at flourishing towns,

men and women. They follow me

in countless numbers, asking for a short cut (atarpos)68 to profit (kerdos),

some eager for divination (mantosuneôn), some for diseases

of all kinds seeking to hear an oracle (baxin) of healing,

for too long having been pierced by pain.69

Empedocles claims to be a god and no longer mortal. His actual claim is theos ambrotos, ouketi thnêtos. Now ambrotos can mean ‘immortal, divine, of persons as well as things’ (LSJ). What I have translated here as ‘profit’ (kerdos) can also have a sense of ‘cunning arts, wiles’ (LSJ),70 which may fit well if we are going to take divination and healing oracles in a magical sense.71 If the learning process for magic was supposed to be long, one can then see why the masses would ask for a short cut to knowledge of ‘cunning arts, wiles’, though even if we take atarpos in the sense of route the crowd may still be asking for magical knowledge rather than simply material gain. Empedocles also at least appears to make the claim that he is able to engage in divination and is able to give oracles of healing.

Again, one can attempt a naturalistic and deflationary reading of this passage. On this reading it is the crowd, the credulous masses, who are eager for divination and a healing oracle and nothing is said on whether Empedocles can supply these or not. Alternatively, one can take divination here in the sense of prognosis, perhaps in the way that the Hippocratics took prognosis to be properly grounded foresight and the proposed healing to be natural, or perhaps magical in some sense and natural.72 The crowd would like a route or a short cut to profit simply considered financially with no magical sense here.

The real problem is Empedocles’ claim to be a god and no longer mortal. One might argue that Empedocles does not claim that he is an immortal god, but that he is an ‘immortal god to you (humin), a very different proposition. You, the credulous masses, may be wrong, especially given Empedocles’ view of the masses.73 That he is honoured ‘as is fitting’ need not imply he actually is a god, but that it is fitting that he be honoured if the masses think he is a god.

Against this deflationary view, Empedocles does claim to be a god in several other passages and claims to be superior to mortal men.74 Presumably he does not die and is in some sense a god. We can also look to Empedocles 146:

In the end they are prophets (manteis) and minstrels and doctors and foremost men among those who dwell on earth, they then rise up as gods of highest honour.75

The standard view of fragment 146 is that Empedocles lays claim to all four of the activities mentioned here and so sees himself as someone who has risen to be a god. That he mentions prophecy here is not problematic if again we take the Hippocratic line on prophecy, though here one might worry that he means prophecy rather more broadly than medical prognosis. The question then is whether Empedocles’ physics can accommodate gods and the process of becoming a god.

Metempsychosis

Empedocles seems to have believed in metempsychosis, the transmigration of the soul from one body to another after death. This is most simply stated in Empedocles Fr. 117:

Prior to now at some stage I have been boy and girl, bush, bird and a mute fish of the sea.76

That needs to be put in a broader context though and it is notable that Empedocles says that he has been many things before but does not assert universal metempsychosis. In relation to this one might read Empedocles Fr. 113 in a different light:

I am superior to mortal men who die many times (poluphthereôn).77

poluphthereôn here is ambiguous between dies many times or can be destroyed in many ways. So one might read this as Empedocles being immortal and being superior to men who have a cycle of reincarnations, or as Empedocles being subject to reincarnation while men die once, being destroyed once and for all in many different ways. Fr. 115 sets a background to metempsychosis with the breaking of an oath followed by exile for 30,000 years and undergoing a cycle of reincarnations of mortal forms.78 Empedocles admits:

I too am one of these, a fugitive from the gods and a wanderer, having placed my trust in raving Strife.79

Again, there is an ambiguity here though. Empedocles may be the only one, or one of a few to break the oath and so his reincarnation cycle is an exception among humans. Alternatively, if we are reading this allegorically and what is happening at one level is the breaking of the sphere by strife and all the elements are then exiled, then metempsychosis may apply to all human beings. There is also an issue of immortality for Empedocles. Gods who are ‘long-lived’ might be accommodated in the physics, their lifespan ending with the total dominance of Love or Strife. Genuinely immortal gods though would be more problematic. In Fr. 112, we noted that Empedocles’ claim was theos ambrotos, ouketi thnêtos. So while he is no longer mortal, if we take ambrotos as divine, he does not claim the stronger form of immortality either. However, Fr. 147 comments on:

Sharing hearth and table with other immortals (athanatois), being free of the woes of men and untiring.80

That looks more problematic unless we take it that in all places immortal simply means long-lived for Empedocles with no contrast between the two.

Related to the belief in metempsychosis was a prohibition on eating meat. So Empedocles asks in Fr. 136:

Will you not end this noise of slaughter? Do you not realise you are eating each other on account of your careless thinking?81

Empedocles includes himself in this:

Woe that the pitiless day did not first destroy me, before for my lips I devised the cruel deed of flesh eating.82

Clearly there are similarities with the Pythagoreans here, and Empedocles is also adamant that one should not eat beans:

Wretches, utter wretches, keep your hands off of beans!83

The breadth of these prohibitions, especially Fr. 136 would suggest that all humans are subject to metempsychosis and so if Empedocles thinks himself above humans, he may well think himself to be immortal. Much of the analysis of Pythagorean metempsychosis is going to apply to Empedocles as well. We have very little definite information on the nature of Empedoclean metempsychosis. We have little on Empedocles’ account of the soul and we do not know if the entire soul or only part of it was supposed to transmigrate. We have nothing at all on the nature of the actual transmigration, of how the soul moved from its previous host body to the next host body. We do know some more with Empedocles on what sort of living things could host a soul, including a bush, a bird and a fish. Whether the soul was immortal for Empedocles is also a difficult issue. If the soul is some natural entity, or is emergent from natural entities the soul will be destroyed in the cosmic cycle when Love and Strife come into their respective completely dominant phases. However we do not know the nature of the soul for Empedocles and as we have seen, he seems to think that he can make the jump from being a mortal to being a god. Whether that is possible for everyone and whether, if it is possible it happens to everyone are questions we do not have enough information to decide. This uncertainty makes it very difficult to say whether anything non-natural was involved in metempsychosis.

This section brings out one of the major issues in Empedocles scholarship. If there is an ontology of the four elements, Love and Strife, then anything composite will be destroyed in the cosmic cycle. Gods are acceptable within this ontology, natural even if they are generated naturally by the elements, Love and Strife as long as they are long-lived but not immortal. There are though passages, as we have seen, where Empedocles seems to posit immortal gods. If such gods do exist then a fortiori they are going to be outside nature. The attraction of having a unified account of Empedocles’ thought, with the unification taking place around the natural philosophy of the cosmic cycle and the four elements, Love and Strife ontology is very strong.

In many of the presocratic thinkers we have looked at, we find some targeting of Homer and/or Hesiod on the issue of natural explanations, or the targeting of interesting, important or difficult-to-explain phenomena. Although we have a couple of comments on meteorology in Empedocles,84 I do not think we see the targeting of Homer and Hesiod, or of interesting, important or difficult to explain phenomena in the same way. I want to suggest that Empedocles does target Homer, but to emphasise what he believes humans can do rather than to assert natural explanations. Empedocles certainly targets other of his predecessors. It has often been recognised that Empedocles alludes to passages in Parmenides. So Parmenides says that:

With this I finish my reliable account and thought concerning truth. Learn now the beliefs of mortals, listening to the order of my words.85

Empedocles seems to be speaking directly to this when he says:

Listen to the undeceitful passage of my words.86

It is arguable that Empedocles also targets Heraclitus.87 So Fr. 3, ‘Not holding sight to be more trustworthy than hearing’ may be a comment on Heraclitus Fr. 101, ‘Eyes are more accurate witnesses than ears.’88

Empedocles fragment 111 is very important in the context of a critique of Homer. As we have seen, winds and rains in Homer and Hesiod are under the control of the gods. In many of the presocratic thinkers we have looked at, they are seen as entirely natural phenomena. In Empedocles though, there is a claim that humans can have control of the weather. There is also an important point in this line of Fr. 111:

Then again, if you wish (ethelêistha), you will bring on the requiting winds

As Kingsley has pointed out, this phrase is used frequently in Homer and Hesiod in relation to the divine powers of the gods.89 Empedocles then seems to be saying that these powers are not the prerogative of the gods and that humans can exercise them as well. In most of the thinkers we have looked at, there is no realm where the dead have some form of afterlife. Empedocles though seems to believe that Hades exists, and moreover that he can in some way journey there and bring back the strength of a man who has died. That a mortal can do that certainly breaks with Homeric ideas.

Fragment 112 is also important, depending on quite what we consider that Empedocles claims here. If he claims to be an immortal god and we take that as a progression from fragment 146 where ‘prophets and minstrels and doctors and foremost men’ become gods, then certainly that breaks with the Homeric distinction between immortal gods and mortal men. Empedocles may also make a claim to divination and oracular healing and to be able to teach ‘cunning arts, wiles’. If so he is claiming considerable magical powers for himself. That in turn might lead us to reconsider pharmaka in fragment 111 line 1 as claiming some magical medical power rather than simply employing the potions of natural medicine.

The metempsychosis fragments are also significant in this context just as they were for the Pythagoreans. After death there is no longer simply the worthless shadow life,90 but there is the promise of reincarnation.

Empedocles then does not seem to want to emphasise natural explanation in contrast to the views of Homer and Hesiod. Rather, he seems to want to emphasise human power and ability against Homer and Hesiod. So humans can control the weather and bring back from Hades the strength of a man who has died. Humans can become gods and gods can be caught in a cycle of reincarnation. Humans can achieve divination and magical healing. It is possible to argue that Empedocles only argues for what humans are able to do naturally (so e.g. the Hades passage is about medical treatment of near death, rather than necromancy), but if that is so it seems secondary to his emphasis that humans can do what is usually attributed to the gods.

Pythagoras, Empedocles and the canon

In the past few chapters we have looked at Pythagoras, the early Pythagoreans and Empedocles. These are the best candidates from within the standard canon of presocratic philosophers for people who did not entirely reject the non-natural in favour of the natural. If we take the view, for example, that Pythagoras and/or Empedocles did not fully reject the non-natural, is that damaging to what I want to argue in this book? There are two related replies to this. First, primarily this book is an investigation into what natural and non-natural meant for the presocratics and how the views of various presocratic thinkers relate to that distinction. As I said in the introduction, it is not the agenda of this book either to cleanse or to implicate the presocratics or some group of presocratics in relation to belief in the non-natural. Second, part of the outcome of this investigation is that I do indeed want to argue that there is a group of presocratics who rejected the non-natural in favour of the natural. However, this group is not co-extensive with the standard canon of presocratic philosophers. It includes some more people than that canon – many, perhaps all of the Hippocratic writers, possibly some more medical writers like Alkmaeon, the commentator on the Derveni Papyrus and maybe more in their tradition, Thucydides, possibly some playwrights and elements of their audiences. It is quite possible that, without detriment, it includes a few less people than that canon as well, such as Pythagoras and Empedocles.91 Indeed, in one way that would strengthen one thesis of this book, that we need to look carefully on a case by case basis at what each presocratic thought, rather than make broader assumptions on supposed group affiliations.92 That, as we have seen, applies not only to a broad group such as the canon of presocratic philosophers, but sub-groups such as the Hippocratics and the early Pythagoreans as well.

Conclusion

It is possible to make a case that Empedocles used entirely natural explanations, based on his ontology of the four elements along with Love and Strife. It is quite possible to construe the actions of Love and Strife as entirely natural, even if we believe them to act in a sympathetic manner. We can take a deflationary view of Fr. 111 and Fr. 112 such that nothing non-natural, at least from Empedocles’ point of view, is being asserted. That there is such a strong natural account of cosmogony, zoogony and the cosmic cycle indicates that this is a strategy we should at least consider. It is also possible to understand Empedocles’ references to ‘long-lived gods’ on this account, as part of the cosmic cycle who live many times the lifespan of humans but perish when Love or Strife become completely ascendant.

However, there are passages where Empedocles appears to posit immortal beings and even passages where he claims to be a god himself. As nothing natural can be immortal for Empedocles, that seems to put these entities outside of nature. Fragments 111 and 112 can be read as claims to divination, magical healing, being able to control the weather and being able to bring the strength of a dead man back from Hades. There is also the consideration that if Empedocles claims to be a god and claims to be able to control the weather, in contrast to the tradition we have traced from Anaximander on, Empedocles has the gods controlling the weather.

Empedocles seems to have had a different agenda in relation to Homer and Hesiod to many of the thinkers we have looked at so far. Where many presocratic thinkers targeted Homer and Hesiod and gave natural explanations for important phenomena, Empedocles appears keener to emphasise the abilities of humans relative to the accounts of Homer and Hesiod. Those abilities seem self-consciously magical and it is very hard to see them all as natural magic.

How far did Empedocles’ influence spread among those who did not take him to be a natural philosopher? There is the tale that Empedocles died by leaping into the volcano at Etna, with variations of the tale having him wearing a bronze sandal which the volcano spits out again.93 Whether he did so or not (and personally I am sceptical) the important thing is the symbolism of the tale for his followers. The leap into the volcano can be taken as symbolic of ritual purification and a voluntary descent into the underworld. A single bronze sandal was the symbol of a magician.94 Those who generated or embellished this tale clearly took this side of Empedocles seriously. That is an important counterpoint to the way that the philosophical tradition, following Aristotle, took him to be a natural philosopher. As with the early Pythagoreans, we have no way of knowing how widespread this view of Empedocles was.

My conclusion here is somewhat cautious as Empedoclean scholarship is in a state of flux. Recent work has made interesting attempts to understand the status of the long-lived gods as part of the natural physics of the cosmic cycle.95 It may be that we can understand the claims of Fr. 111 and Fr. 112 in a natural manner, especially given the extensive natural explanations of cosmogony, zoogony and the cosmic cycle in general. Despite (what appear to us to be) the idiosyncrasies of Empedocles’ system, he may have considered it himself to have been entirely natural. If we cannot deflate or explain the claims of Fr. 111 and Fr. 112 though Empedocles does make claim to non-natural abilities. One concern here is his agenda in relation to Homer, which does not seem to want to emphasise natural against non-natural explanation, but that humans can do what had previously been attributed to the gods.