Most people believe that getting promoted is a reward for past performance. This is absolutely false.

Employers are not rewarding strong performers for their past contributions; they are investing in their future contributions. The sooner you grasp this fundamental truth, the closer you will be to getting promoted.

So, no matter what you have done in the past, the boss really doesn’t care. What she cares about is what you can do for her (and the company) in your new position. Your past only serves as an indication of what you might do in the future, one piece of evidence, at best. It is only what you may do in the future that drives the promotion decision.

One of the worst political campaigns I ever saw was for a local politician who had signs all over town that said: “Vote for X. She’s earned it!” as if getting elected were something you earn. You do not earn a promotion by past performance. You prove you are the optimum choice to deliver future performance.

This was basically Bob Dole’s campaign for president in 1996. His campaign could be reduced to this slogan: “Vote for Bob Dole. It’s his turn,” the presidential equivalent of “He’s earned it.” The voters chose a future with clearer definition, and Bill Clinton went on to an eventful second term.

So you don’t bank Brownie points to get promoted. If you’ve been working hard and are still waiting to be noticed and rewarded, you may be in for disappointment. Promotions are the ultimate case of “What have you done for me lately?” In fact, employers really don’t want to know what you’ve done, even lately. They want proof that you can deliver a specific, clearly targeted future.

Right now, all over the world, there are angry, frustrated people who have been passed over for promotions—passed over in spite of their loyalty, performance, skills, and belief that they’d earned it and it was their turn.

To get promoted, you have to offer the best future out of the available options.

Companies don’t hire the best person for the job; they optimize the outcome of the staffing change. So not only are you competing with all the other people who may want the new job, you’re competing with the company’s impression of the benefits of leaving you where you are versus the risks of giving you the promotion.

If you’re more valuable where you are, you won’t be getting that promotion.

Even if you have the entire skillset they need for the new position, there are several reasons you might be more valuable where you are:

Promoting in-house creates two staffing changes; hiring from the outside involves only one.

Promoting in-house creates two staffing changes; hiring from the outside involves only one.

Your skills may be rare and difficult to replace, while the new job requires skills that are rather easy to procure from someone else. (This may be true even if the new job pays significantly more.)

Your skills may be rare and difficult to replace, while the new job requires skills that are rather easy to procure from someone else. (This may be true even if the new job pays significantly more.)

If you have created a feathered nest with your personal stamp on every aspect of what you do, staff that is loyal only to you, procedures known only to you, and so on, dislodging you could be too disruptive to the organization.

If you have created a feathered nest with your personal stamp on every aspect of what you do, staff that is loyal only to you, procedures known only to you, and so on, dislodging you could be too disruptive to the organization.

You may be in the middle of a critical, high-value project, and your removal would be too disruptive.

You may be in the middle of a critical, high-value project, and your removal would be too disruptive.

External customers may be addicted to you, and your reassignment could exact too high a cost from those relationships.

External customers may be addicted to you, and your reassignment could exact too high a cost from those relationships.

You may be so efficient and cost-effective where you are that managers fear your removal may invoke large and unpredictable costs.

You may be so efficient and cost-effective where you are that managers fear your removal may invoke large and unpredictable costs.

Cost has many factors. Some of the most significant costs associated with staffing changes are recruiting and onboarding a replacement as well as disruption to the existing functions managed by the employee who might be promoted.

Human resources professionals have gotten pretty good at estimating direct recruiting and onboarding costs for hiring different levels of staff: At the executive level, a common H.R. rule of thumb is that it will cost 1.5 times the annual salary to recruit and onboard a corporate officer or function head. Even a receptionist can cost thousands of dollars in recruiting and agency fees, testing, management time for interviewing, training, and so on.

If it costs more to replace you than to hire someone else, they’ll hire someone else.

One way to tip this analysis in your favor is to keep the company from running two simultaneous placement efforts—or any at all. Offer yourself for the promotion before a search is launched for the desired position so you can cite those savings as part of your rationale. If possible, identify someone ready, willing, and qualified to replace you to further reduce the cost of promoting you.

The cost of the disruption of your leaving a current assignment is harder to estimate and often much greater than the cost of outside recruitment. The loss of productivity when a strong performer is taken from a unit can have a significant impact on that unit’s bottom line, and even a talented incoming manager may face a long learning curve before hitting his stride in a new assignment. (If companies had accurate data on these costs, they’d spend a lot more time and energy on retention.)

Because the costs of staffing adjustments are not easily estimable, most managers just throw them into risk analysis. But cost and risk are not the same thing. Costs are estimable, finite, and numeric; they’re not scary. Risks are, by definition, scary, unknown, and unpredictable. A manager who might not at all fear the cost of promoting you, might blanch at the risk of promoting you: What is the worst thing that can happen if we promote Karen? Will she succeed in the new unit? Will her old unit fall apart? Is she gunning for my job? Will she leave the company anyway?

The risks associated with promoting you must be manageable and perceived as less horrific than the risks associated with hiring or promoting someone else.

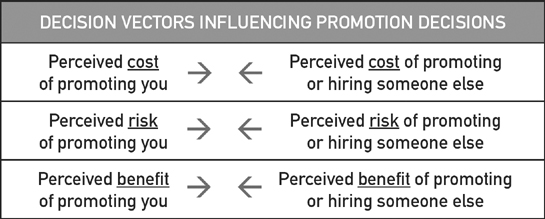

You must provide more benefits and fewer costs and risks than the other choices your manager has. Most people seeking a promotion pay more attention to promising benefits than they do to alleviating costs and mitigating risks, but all three are critical in any decision to promote from within.

You must pass all three of these vector tests to be promoted. Sometimes an internal candidate passes two of the three criteria: Perhaps she can be replaced at modest cost and promises to be a strong contributor, but the risk is too great.

Top performers are often passed over because of the risk factor. Top performers are by definition not like the rest of us. Many are difficult and temperamental people. They’ve lived in a world designed for the averages; they are often frustrated, or they may be rule breakers. Are you known as reliable? Or are you a strong contributor with a tragic flaw, like a hot temper or a habit of blowing off assignments that don’t interest you? When managers do risk analysis, they must project worst-case scenarios. If the risk is too great, all the benefits in the world will be passed over in favor of a less risky alternative.

Also, note the use of the term “perceived” in Figure 1.1. Perception is reality when it comes to management. If management perceives you as risky, highly talented, diligent, or prone to gaffs, then that perception is your reality. So you need to worry about how others perceive you at least as much as you worry about your work. We’ll have more to say about this in later chapters.

Why Buddy Didn’t Make Sales Manager

Buddy R. was the top salesman at a Ford dealership. He sold twice as many cars as any two other sales reps. Buddy had three talents that made him number one: First, he had a knack for establishing rapport with customers of any background. He could sell a new Crown Victoria to a neurosurgeon in the morning and a used F-150 pickup to a construction worker with limited English that afternoon. Second, he had the ability to remain focused on one sale at a time, giving him a high one-visit sales rate and reducing the need to share commissions with other reps who might end up taking over a handoff. Third, he had a genius for spotting buyers. He could look across the lot and tell you who was just a tire kicker and who would buy a car that day. Buddy only approached buyers.

So why was Buddy passed over for sales manager? Buddy came in late, he skipped “mandatory” sales meetings, he ignored his assigned floor duty, and walked right past customers he didn’t think were going to buy, in effect dumping them on the other reps. Buddy was an unapologetic prima donna sales god who got away with behavior that would get other reps fired. They all resented Buddy. And one of them got promoted instead of Buddy.

Why Buddy Didn’t Make Sales Manager

Madison D. was an attorney at a Manhattan-based boutique firm specializing in complex family trusts and estates. She was a star performer, seemingly with the whole package. She worked long hours. She was good at staff development and ran a tight team. She was one of the firm’s top billers and a rainmaker. All of this should have put her in the running to make partner. So why was Madison passed over again and again?

Ironically, it was because of her rainmaking technique: Madison trolled for new clients in bars frequented by Wall Street types.

The partners loved all the new accounts, but they worried about her drinking. Since the firm specialized in services for high-net-worth families (trusts and estates), they were particularly sensitive about their reputation. So, again, a top performer was denied promotion because of a risk analysis.

Suppose you have no fatal flaws, you’ve anticipated and acquired the needed skillset, and you are a well-regarded standout among your peers. So how could you be passed over for promotion? Simple: You may be the best person for the job, but you may not be available to take the job! Whether a promotion involves filling a new position or replacing an existing one, the organization is going to want that job filled on a specific schedule. There may be some flexibility, but if you cannot be extracted from your current duties to achieve a smooth handoff within the window of opportunity, someone else will be getting the new assignment.

Ambitious people tend to get critical assignments. But if having a full plate keeps you from appearing available when a new opportunity arises, you’ll be passed over, possibly in favor of some laggard who appears to have plenty of time to take on new duties.

People who get promoted again and again tell me that working the clock is a critical skill. You might get lucky once or twice in a career and have your availability magically coincide with an internal opportunity, but the most successful people systematically make themselves available as opportunities arise.

Three factors come into play here:

You need to know about internal opportunities before they’re posted. Once an opportunity is posted, several things have already happened: A lot of competition will have been alerted to the opportunity, and you will have to be demonstrably better than anyone else to get the assignment. Worse than that, H.R. will have gotten involved. A position description and skillset analysis will have been written that may not favor you, and there will be a process and a timeline assigned for making a placement that might not match your availability. So waiting for a posting has definite downsides.

People who manage their careers, as opposed to just experience them, process more information than other people. They see beyond their own tasks and job. They see an intertwined network of internal and external forces working on sectors of the organization. They anticipate senior management moves.

In short, they have a nose for change, and they place themselves in front of that change, ready to capitalize on it and contribute to the organization’s response to that change.

Whether the change is positive or negative is not that important. It’s the change itself that creates the opportunity for advantage. An aggressive careerist can turn even an apparent disaster to his advantage. For example, if the company is going to move an entire business unit offshore, most of the people in the unit would consider that a disaster. But a real careerist would see it coming and either jump to another unit before the RIFs begin or become the person managing the offshoring process and perhaps even continue as an HQ liaison to that overseas function.

How Mary C. Got Promoted to Assistant Dean

Mary worked in administration for an old-line college on the East Coast. She had had several assignments of increasing responsibility in both housing and student affairs but just couldn’t break out of the “coordinator” and “administrator” title cluster. Through her many connections, she began to hear rumblings that the president thought the institution had too many layers of administration and too many career employees whose hearts weren’t really in service delivery.

So on her own she researched organizational consultants who were active in higher education and called same-level colleagues at other institutions and asked them what had happened in reorganizations. While most employees ignored the president’s signals, she got on his calendar, dropped the names of several consulting firms, described events at other institutions that had addressed administrative stagnation, and even volunteered to do a white paper if he was interested, making it sound like it would be no big thing. He was interested. When she presented her findings on best practices and academic restructuring, she made it clear that she was interested in managing such a project, and sure enough, when a pilot restructuring project came up, Mary C. got the assignment, along with the title of ‘acting’ assistant dean. When the project turned out to be a success, she got the “acting” dropped. In the end she restructured the entire student services function.

She accomplished her long-term goal by taking a series of small steps: She anticipated institutional needs, developed a knowledge base on her own and ahead of anyone else, volunteered to solve a problem before anyone else got the assignment, and thus had already proven her future value when the opportunity to pilot the project arose.

She got promoted in a bureaucratic, seniority-laden system, while older workers with better credentials were still “waiting their turn.” Hers is a textbook example of how to get promoted.

We’ll talk more about how to get this information in the next chapter, but for now, let’s consider changes that are typical in any organization and how they might affect you. Their power to impact you depends on where you are in the org chart. If you are a senior person, you need to worry more about potential staffing changes at the top, external forces, competitors, and the economy as a whole. If you are just starting in your career, you need to worry more about your department, your immediate work area, and the personalities of the people closest to you. And everybody needs to worry about the alignment of one’s duties with organizational strategy and priorities. If you’re working on something that becomes unimportant, you’re at risk whether you are a strong performer or not. On the other hand, if you succeed with a project that is critical to advancing an organizational goal, that contribution will get noticed.

So the question is: Are you avoiding learning something that you need to know to make it to the next level? Has your boss dropped any hints about further training to acquire a new skill? If so, you’d better pay attention. The alternative to advancement is not always stagnation—sometimes it’s removal.

The following are some examples of observations that, if acted upon, can give you the edge.

Your competitor is about to launch a product or service similar to the one you’ve been working on.

Your competitor is about to launch a product or service similar to the one you’ve been working on.

A critical worker is about to retire.

A critical worker is about to retire.

Your company’s revenues have tanked, and budgets are going to be a problem.

Your company’s revenues have tanked, and budgets are going to be a problem.

You hear through the grapevine that a coworker interviewed with another company for a job.

You hear through the grapevine that a coworker interviewed with another company for a job.

A new manager is coming on board one, two, or even three levels up from you.

A new manager is coming on board one, two, or even three levels up from you.

A critical worker one or two steps up from you is pregnant and may be taking maternity leave during a time a critical project is due.

A critical worker one or two steps up from you is pregnant and may be taking maternity leave during a time a critical project is due.

The company bought a competitor or vendor and needs to integrate or reorganize the acquisition.

The company bought a competitor or vendor and needs to integrate or reorganize the acquisition.

Your boss gripes about a problem, or your boss’s boss gripes about a problem.

Your boss gripes about a problem, or your boss’s boss gripes about a problem.

The company wants to commercialize a product, enter a new market, start exporting, install CRM, become ISO certified, or the like.

The company wants to commercialize a product, enter a new market, start exporting, install CRM, become ISO certified, or the like.

Of course you should read the internal job postings on your company’s intranet every day with your morning coffee, but it is anticipating organizational needs that drives a true competitive advantage. Once that posting is public—even internally—you’re going to face competition, an existing job description, and managers who have envisioned a solution that may not look like you.

Once you hear about or conceive of a possible opportunity, to position yourself to execute a solution, you will need to establish three things with your boss:

When it comes to skillset, have a little confidence in yourself! Don’t over-estimate the requirements. Getting a friend to show you how some software works may enable you to grab an opportunity, while waiting to take a training program may allow the window of opportunity to slam shut.

Of course you should go to training classes and conventions, but the point is, don’t delay pitching yourself for an opportunity, because timing is so critical. If you wait to develop deep expertise, you’ll be useful to the person who was hired to solve the problem while you were gaining deep expertise.

And you have to have more than skills, anyway. You have to bring ideas to each endeavor. There are plenty of employees who make great soldiers implementing someone else’s plans. But the people who advance quickly bring ideas and can create plans. So when you approach a boss about a problem, offer yourself as the solution to that problem.

Always provide more than one possible solution to a problem. Don’t hesitate to walk into your boss’s office and say, “I wonder if we could solve this problem by _______ or _______ or _______.” Be flexible in the give and take of decision-making. Don’t love any one idea more than you love solving the problem! Let your boss participate in the solution, developing your idea into one she can own. The smartest subordinates can walk into their boss’s office and say, “I think we should paint the walls green, the color of money!” and before they leave, they’ll have convinced their boss that the whole thing was the boss’s idea in the first place. More commonly, the boss will take your idea, change it, and begin to formulate a plan to implement it. Do your best to be the instrument of that change.

Being available can be crucial. A friend of mine was up for advancement in the H.R. department of a large bank. She was a superstar who everyone thought was being groomed to be the future head of the department. But she missed a key promotion because she was put in charge of a headquarters move that made her unavailable for one full year. Right in the middle of that year, her dream assignment came up but was awarded to one of her rivals.

During that year, the bank went global, putting its first branches in Taiwan and Singapore, hiring its first offshore workers, and setting up its first offshore H.R. function. That was the assignment she missed. A headquarters move is critical, but not sexy. Going global is sexy, and she missed out.

You have to be able to draw your work into some kind of closure, and hand it off, to be promoted. If a rival is ready and you’re not, she may get the nod while you are passed over.

The savvy careerist intentionally finishes projects just as a promotion becomes actionable. He’ll speed up, slow down, hand off, or whatever it takes to make the timing work. Managing time in concert with the needs of the larger organization can make a huge difference in career advancement.

You want to be the person senior managers think of automatically when new opportunities come up. You have to be seen as someone who can finish projects. Follow-through, completion, and being ready to pick up the next project—this is the description of you that you want in the minds of the decision makers.

In order to minimize any problems associated with leaving your old assignment, as well as maximize your attractiveness for the projected new assignment, never be irreplaceable.

Irreplaceable people are never promoted. You may be on a critical assignment that makes you temporarily irreplaceable, but in every organization there are some irreplaceable people who are intentionally so. To make themselves feel important and indispensable, they withhold critical data from others, refuse to delegate anything but the most mundane tasks, and retain all decision-making authority. They actually create a scenario in which their absence from work, for even a day, brings their unit or department to a halt until their return.

They are often talented people actually working at assignments below their abilities. By creating complexity in a function that doesn’t necessarily require it, they appear indispensable. Or they may be limited in their organizational and procedural abilities, preferring to embody in themselves all the structure that their function may require. Over time, they’ve come to be their position rather than serve in it.

Irreplaceable people are the long-tenured accounts-payable clerk who refuses to train anyone in his function; the trust officer at a bank who just “knows” all the accounts and all their arcane rules; the foreign sales rep who refuses to introduce any junior people to his accounts; the project engineer who withholds key information from her teams and thus will always be a project engineer; the legal secretary whose boss cannot get along without her. None of these people can be promoted.

To be a fast-track person you need to make yourself easily replaceable. To accomplish this you will need to:

Document your job.

Document your job.

Train and develop your subordinates.

Train and develop your subordinates.

Cross-train your lateral colleagues to cover your position.

Cross-train your lateral colleagues to cover your position.

Pick a lieutenant and be sure she is ready to step into your shoes.

Pick a lieutenant and be sure she is ready to step into your shoes.

Documenting your job means that you have written procedures for everything you do, ready and available for your replacement. Policies, procedures, techniques, decision triggers, suppliers, vendors, the secret sauce recipe, all of these can be compiled in binders or intranet files. These, plus the assurance that you will be available to answer questions, can be a one-way ticket to advancement.

Be generous training and developing your staff. As your staff becomes better able to cover for one another, your organizational systems will be more successful. Relying on structures to get work done is safer than relying on personalities. And anybody who relies on heroes or irreplaceable people is at their mercy.

I once had a contract with AT&T to teach internal job-seeking skills to all the workers in a business unit. I thought the unit manager was crazy, that he would lose all his best people. He pulled me aside and said, “AT&T has just decided that a major identifier of executive talent is going to be how well we develop subordinates to take on leadership roles after they leave the unit. I’ll take care of training and developing them, and you be sure they get promoted. I’ve got some really good people right now, and I think this can be a breakout move for my career.” And it was.

In case you’ve never thought about it, teaching is a critical executive skill. CEOs spend a lot of their time making presentations, giving speeches, conveying ideas, and arguing against bad thinking in the organization. They are teachers in the truest sense of the word. Teaching, training, developing, guiding, and mentoring your subordinates can be career-advancing practices. And if you can’t do this yourself, if you’re not naturally a teacher, outsource the function to others within and outside your organization.

And you do not have to have a big staff or an important leadership role in order to implement this career strategy. You can start to become known as a trainer and developer of staff. If a new janitor is hired and you’re already a janitor, volunteer to train the new hire. Training is a promotable skill, and it becomes more important, not less, as you rise up in the org chart.

You need to have your own succession plan. Who will replace you if you are promoted? If you have someone in mind, you can bring this information into the promotion equation. If you can be easily replaced because of timing factors or because you’ve done a good job of developing a subordinate or you have someone else in mind who could take over, you may get the nod even if your rival for the promotion is a much better performer.

Remember, organizations optimize the outcome of the staffing change. They don’t hire or promote the best person for the job. Being easily and smoothly replaceable is, in fact, a major part of reducing the resistance to promoting you.

High performers are like engineers. They’re always working themselves out of a job. There’s an old joke among engineers: An engineer and a priest die together in a car accident. The priest is absolutely delighted with the afterlife. “This must be Heaven,” says the priest. “Look at this magnificent city of gold.”

“No, Father,” says the engineer. “This surely must be Hell, for I can see that everything already works perfectly here.”

INTERVIEW WITH AN

ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE IN

PUBLIC RELATIONS

Since I knew you were coming over today, I came up with my own Top Ten career points for the overly ambitious.

That’s everything I know about getting promoted, but I’m learning more every day. Come back and interview me again in a year.