Fortune favors the prepared mind.

—LOUIS PASTEUR

Lifelong learning used to be the province of medical doctors and scientists, but now it is a requirement for all careerists. What’s different about fast-track people is that they anticipate the needs of their organizations. They are true lifelong learners, acquiring new skills on an ongoing basis with a strategy in mind: to have the skills they need for their next assignment before that assignment is even available to them.

Social scientists agree that we are living in a period of rapidly increasing complexity. Skillsets that used to get you into senior management now won’t grant you success in middle management. Do you have a strategy to obtain the skills you will need to advance to the next level, to be ready to be promoted, and to be ready to perform if you are promoted? Perhaps we should forget about advancement and promotions for just a moment and talk about survival. Do you have a strategy to keep up with changes in your current field, or will change overtake you?

The days of leaving learning at the edge of the university campus are over. College and even graduate degrees are a smaller part of the formula for success than ever before. It is the ongoing, nimble, responsive and anticipatory learner who has a career advantage over others. Those who can design their own educational process, who teach themselves what they need to know, are known as autodidacts. We are entering the age of the autodidact.

Even if you have no degrees at all, you can be an autodidact. The only thing degrees confer is the imprimatur of the institutions that grant them. They indicate learning, but it is the learning itself that is critical to success.

Lifelong learning is a smorgasbord approach. You have to take it from wherever you can get it. Here are just a few of the sources:

Internet. Search topics important in your business, taking care to sort out the garbage.

Internet. Search topics important in your business, taking care to sort out the garbage.

Read several newspapers a day.

Read several newspapers a day.

Read all the trade publications for your field, trade, or discipline.

Read all the trade publications for your field, trade, or discipline.

Structure library learning on a topic of interest.

Structure library learning on a topic of interest.

Get advice from or even consulting with subject-matter experts.

Get advice from or even consulting with subject-matter experts.

Develop in-house or external soft skills, such as leadership or EQ.

Develop in-house or external soft skills, such as leadership or EQ.

Develop in-house or external hard skills, such as changes in GAAP, or Sarbanes-Oxley compliance or how to speak conversational French.

Develop in-house or external hard skills, such as changes in GAAP, or Sarbanes-Oxley compliance or how to speak conversational French.

Get vendor training or certification classes.

Get vendor training or certification classes.

Join a trade association and attend their training conferences and/or conventions, and subscribe to their member journals and newsletters.

Join a trade association and attend their training conferences and/or conventions, and subscribe to their member journals and newsletters.

Attend management or executive retreats addressing a relevant topic or concern.

Attend management or executive retreats addressing a relevant topic or concern.

Pursue executive development provided by the top business schools on topics of interest, such as globalism or developments in supply chain logistics or economic trends impacting an entire industry (generally considered post-MBA in content).

Pursue executive development provided by the top business schools on topics of interest, such as globalism or developments in supply chain logistics or economic trends impacting an entire industry (generally considered post-MBA in content).

Read your organization’s in-house materials, such as manuals, product information, policies, and procedures, and discover secrets deeply hidden in obscure pages of its intranet.

Read your organization’s in-house materials, such as manuals, product information, policies, and procedures, and discover secrets deeply hidden in obscure pages of its intranet.

There are graduate and undergraduate degrees and certificates, offered by colleges and universities, coming in a complete range of formats: online (asynchronous or synchronous), distributed learning with intensives offered at various times of the year followed by periods of self-study, weekends or evening programs (cohort or noncohort), classes offered onsite at your employer’s or offsite in a hotel, or more traditional residential programs with semesters or quarters and classes that begin with a bell.

There are graduate and undergraduate degrees and certificates, offered by colleges and universities, coming in a complete range of formats: online (asynchronous or synchronous), distributed learning with intensives offered at various times of the year followed by periods of self-study, weekends or evening programs (cohort or noncohort), classes offered onsite at your employer’s or offsite in a hotel, or more traditional residential programs with semesters or quarters and classes that begin with a bell.

Evening and weekend courses are available from seminar companies in every major city.

Evening and weekend courses are available from seminar companies in every major city.

Enroll in Toastmaster’s International to develop your speaking skills.

Enroll in Toastmaster’s International to develop your speaking skills.

Find and talk to people who know what you need to learn.

Find and talk to people who know what you need to learn.

What else? Be creative!

What else? Be creative!

Do You Read the Newspaper?

Most young people today get their news from the Internet, but news sites contain approximately one twenty-fifth of the words in the news sections of a newspaper. So you may be missing a lot of information critical to your success.

Warren Buffet, the Oracle of Omaha, self-made billionaire, and at last count the second richest-man in the world, reads four newspapers a day to keep up on news and trends.

Howard Schultz, CEO of Starbucks, reads three newspapers a day with his morning coffee, and it seems to have helped him run a successful company.

I’ve been reading three or four newspapers a day for decades—so far to no effect.

Education has changed tremendously over the last twenty years, with an explosion of options never before available to working people. Now it is possible to pursue all kinds of educational attainment even while employed, and even if you have kids and a spouse, travel a lot, or have a big and active life outside of your job.

You can even obtain a Ph.D. while working full-time, through such wonderful, accredited options as Fielding Graduate University of Santa Barbara, California, and similar institutions offering a distributed learning model where you meet occasionally throughout the year and complete the rest of the program through distance learning. These types of programs didn’t even exist until recently.

But it is not just whether you are learning constantly; it is also important what you are learning—and how relevant it is. This is why it is a huge career advantage to be an autodidact. You can obtain critical skills on the fly, as needed, and on short notice. You can obtain the right skills and the needed skills in a timely manner.

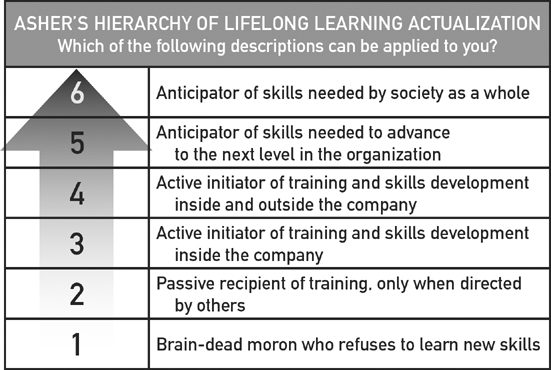

For example, are you active or passive when it comes to obtaining new skills? Do you reluctantly attend training classes as directed by your boss or by H.R. mandates, or do you seek out the training and skills development you need to advance to the next level? Are you willing to spend your own money to join critical trade organizations, attend association meetings, or obtain outside vendor training important for your own success and advancement? Most important of all, both to yourself and to your employer, do you anticipate your organization’s future needs, obtain those skills on your own, and then offer them when your employer needs them?

Here’s how H.R. professionals design a skillset intervention for an individual manager or for any class of workers:

Obviously, you need to do this yourself, before your boss or H.R. manager does it. As important as H.R. is, it is basically a reactive function. You need to be prescient, anticipatory, and ahead of the curve. Look at step number one above. Do you habitually do this?

Remember, you don’t necessarily have to be expert to win an assignment! Exposure may be enough; knowing the jargon may be enough; a few lunches with a pal who has experience in the target issue may be enough. But timing is everything. You need to act fast, before anyone else, because once H.R. gets ahold of it, a Ph.D. may be required.

One critical indicator of how committed you are to your own self-development is whether you will spend your own money on it. If your employer won’t pay for you to belong to an organization, attend its meetings, or take a class outside your assignment area, will you pay for it? If not, you may just be a tourist in career land.

Note that this hierarchy reaches outside the organization to ask what skills society as a whole may need of its member-participants. This is in alignment with systems theory, current concerns of global sustainability, and a new accounting concept called the triple bottom line. The triple bottom line asks these three questions:

We are leaving an era of hedonism and me-first-ism and entering an era of renewed interest in boundary-spanning communitarian ethics, with a much bigger picture of what constitutes a community. Globalism can be viewed in different ways. The first wave was: Where in the world can I obtain more production or markets? The next wave is this: What are the impacts anywhere in the world of my decisions and actions?

Let us all hope that completing this shift does not come too late.

Things change, and if you don’t change with them, you’ll become a dinosaur. Even young people can be dinosaurs if they hang on to old ideas they inherited from their families or from growing up in a particular area of the country.

Hanging on to old skills, and refusing to learn new skills, can make you a dinosaur but so can hanging on to old concepts and old values.

Can you anticipate practices that are accepted today that will be abhorred about five minutes from now? Here’s one: doing business in strip clubs. Here’s another: exporting pollution to minority neighborhoods, rural areas, and foreign countries. And here’s one more: companies that habitually abuse their employees will have serious retention problems as the pendulum swings back in favor of employees in the coming years. Anticipate these social changes, and you’ll be ahead of other careerists and more valuable to your organization. Long-term career success is enhanced by being a bit of a futurist.

Notes from a Veteran Chief Technical Officer in the Silicon Valley

“We employ two types of people: People who just do their jobs—who got into this because when they were in college we were a hot sector—and people who live and breathe technology. I can tell the difference in a few moments. Unfortunately, the guy before me hired a bunch of people who are just putting in their time. He was from [a large company] and he bought credentials. I never buy credentials. I ask a guy what he does at night, and on weekends, and I listen really carefully to what he says about working on a problem. If he stops thinking about that problem at night, he’s not my type of [employee].”

When you read a book, go to a website, take a class, or read a policies and procedures manual, you are learning information that was originally embodied in a live human being. Someone had the insight that was then recorded in some media, and as a student or investigator, you are accessing that information later.

Perhaps the best source of information is to go directly to those live human beings themselves, the ones who originally had the insights.

Part of lifelong learning is to learn from others who possess the information you need to obtain. When you read management books that talk about having a large network and having many mentors, what they mean is having direct access to people who can tell you how things work, how to solve problems, where to find help, and so on.

Be aware that sometimes the people with the most and best information are not necessarily people with position authority, with titles like head cashier, CTO, or director of H.R. Often it’s people who have little or no authority who have the most informational power, like the A/P clerk who can tell you how to get your expense reports approved, the secretary who knows how to get a laptop requisition approved, or the person in every office who knows how to update software without losing your old files, and so on.

Overheard in the Bull and Bear

I overheard a guy yelling into his cell phone in the Bull and Bear bar in the Waldorf Astoria on Lexington in Manhattan: “Here’s my promise to you: The minute I’m not learning every day, I’ll submit my resignation. So that’s not an issue.”

Fast-track careerists prefer to get their information from living human beings. Fast-track careerists collect people the way some people collect stamps. They have, literally, hundreds of people whom they can call upon at any given time. And many of them do it systematically. They use contact management software, they write names and title or positions on the back of pictures, or they write down the names of every person at a meeting directly on the file or on the paperwork from that meeting.

Book learners—those who primarily get their information from static media—often don’t become fast-track careerists, because the skills that are required to identify, access, and develop relationships with knowledgeable and powerful people are skills that tend to be rewarded, while information that is recorded in or on media is obsolete. As any teenage girl can tell you, the best way to get the most up-to-the-moment info is to call somebody.

| DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SUPERVISOR, MANAGER, EXECUTIVE, AND LEADER |

|

| POSITION | DUTIES AND SKILLSET REQUIREMENTS |

| SUPERVISOR | Has direct technical expertise; can train others in it. Maintains appropriate social distance between self and those supervised. Has mental toughness to hire and fire. Can set clear expectations for direct reports. Has emotional maturity. Can resolve human conflicts. Can direct the activities of others |

| MANAGER | All of the prior, plus: Monitors the activities of others. Can use data to make and support decisions. Understands a longer cycle of business, that is, can see seasons, product life cycles, budget cycles, and so on. Can execute strategy. Can achieve goals through subordinates; can delegate. |

| EXECUTIVE | All of the prior, plus: Can see strategy of the organization as a whole, can set the direction of the enterprise. Can see the organization in its external context. Can anticipate external threats, including broadly based industry and societal trends. Can achieve goals through subordinate structures, rather than personalities. |

| LEADER | All of the prior, plus: Can inspire. Can achieve efficiency of execution through inspiration rather than direction. Can call upon the power of ideas and moral persuasion, rather than the power of position. Represents the enterprise to society. Influences the practices of external others, be they competitors, suppliers, customers, or unrelated emulators. |

Trade and professional association meetings are the best places to meet people who are leaders in their fields. Belong, and participate. Spend your own money to attend meetings if your employer won’t send you. You are the one who benefits, and you’ll be taking those benefits with you wherever you go.

You need a plan to develop the skillset necessary to deliver the mission of your next job, be it supervisor, manager, executive, or leader. Do you need to learn to give speeches, teach in a seminar format, analyze data, or even play golf? If so, it is your responsibility to obtain those skills in anticipation of your next promotion. For most organizations, it’s skills first, promotion later—not the other way around.

Why People Earn Exactly What They Expect to Earn

For several decades I have been struck by the fact that people are mostly content with their salaries (not young people, certainly, but many people in the middle of their careers). Most people earn about what they expected to earn or are about as happy with their incomes as they expected to be. So why is this?

This is true for the same reason that you find things in the last place you looked. You find things in the last place you looked because once you’ve found something, you no longer need to look for it. Using the exact same human logic, once you earn what you expected to earn, or earn enough to meet your needs, you no longer will switch jobs or careers in order to earn more.

You are content.

So my suggestion to you is rather simple: Be less satisfied. Decide you are worth more. Expect to earn more. And whatever number you choose, within reason, that is the number you will earn.

Vannetta S. was a star performer in technical customer support for a large multinational. She had a couple of favorite sayings: “Always be fabulous!” and “Look good, do good, be good.” Her boss thought he’d found a gold mine when he hired her. She inspired others in the department, including people above her. She earned so many raises that she was bumped to the top of her pay grade, earning the maximum that H.R. rules allowed. But her boss had hiring authority. So Vannetta and the boss made a pact. On Friday evening, as she headed out of the office, she said, “I quit.” And on Monday morning when she came in he said, “You’re rehired.” He processed the paperwork to record her separation, and then he rehired her with a jump in grade. For six months they thought they’d get busted by H.R., but they never heard a word about it. Fabulous!

One of the problems with letting your employer pay for your continuing education is that they often don’t want to pay you more for it later. Before you get too excited about education benefits, check the details. Some don’t pay up front; they only reimburse you for courses you have finished. Many won’t pay for books, fees, and other directly related expenses. There may be restrictions on topics (for example, the course or degree program must be related to your current assignment). And worst of all, many include a pay-back clause if you leave the company before a specified time after you complete the course of study. So your night MBA “paid for” by a company might chain you to that company for five years after graduation. That’s no problem if your compensation is increasing and your advancement is progressing, but five years of career stagnation is not worth any amount of education benefit.

All too often your only reward for completing a degree while with the same employer is a congratulations and a greeting card. That’s a pretty low return on your investment of time and energy, regardless of who pays the tuition.

One way to deal with this is to set clear expectations with your employer that you will get a boost in pay and a new assignment upon completing a certification or degree program.

Interview with a Secretary Promoted to Management

“I was like the last person you would ever think would be promoted. I was a fifty-year-old male secretary who’d been with the organization for twenty years. I was the only gay guy in the department. I was the only one in the department without a college degree. And although I got along with everyone, absolutely no one thought of me as ‘high potential.’

“On top of all that, this place was really old school. They still had us make the coffee and bring the doughnuts, stuff that quit happening in the corporate world twenty years ago. But this was [a health and human services department for a major city]. There was an iron curtain between support staff and professional staff. No one had ever crossed over before.

“You might ask how I came to be in this position, but everyone develops at their own pace. I had some things of my own to work out, and the job wasn’t my top priority for a long time. But then one day it was. So I decided to go to night school. I signed up for a degree completion program that would take two years. It was the smartest thing I ever did. But I asked myself, how am I ever going to get them to take me seriously at work? How am I going to get credit for this degree? And then I had a flash of brilliance.

“I am the one who does all the holiday designs for our department. You want Halloween? You want Fourth of July? That’s me. So I decided to make an installation out of my education. I put up a big banner behind my desk, ‘Robert is going to college!’ It was corny, I know, but it started the conversation. I left that up way too long, a couple of months at least, and then I replaced it with a calendar. The calendar was a countdown to my graduation. ‘Months until Robert graduates from college.’ I left that up for a month or two, until I finally revealed my true intent. I replaced the headline to read ‘Months until Robert is no longer a secretary!’

“I think it was nonthreatening by then. If I’d started out with that, maybe I’d have gotten some criticism. I don’t know. Also, by then, I had almost six months of success in the program. People could see it was not a fad. They could see I was going to make it.

“In the final year, I changed it to be ‘Days until Robert is no longer a secretary!’ I wrote the titles of my papers on the calendar, and people could see that they were related to our mission. Every couple of months I redesigned the thing. Finally, I started putting a big X on each day that brought me closer to graduation. And then a really weird thing started to happen. People began to ask me what kind of assignment I wanted. Everyone in the office was looking for a job for me.

“Even my boss, who made it no secret that she didn’t want me to leave, got the hint. She started referring me for jobs in our organization, and other jobs city-wide. I got a job across the hall as a case manager. I actually got to write the position requisition for my replacement. That was a sweet moment.

“Now I’m signed up for an evening master’s degree. I know I can do more. I probably won’t do the calendar thing again, but it was absolutely the key to my promotion.”

When a Raise Is an Insult

While working for a government agency in California, Maureen D. received a 4 percent management-grade raise, and in the same year a 7 percent merit raise for outstanding performance. H.R. processed the 7 percent raise at 3 percent. When she inquired about the “mistake” they told her that she had already gotten a 4 percent raise. She asked to see the policy that allowed this interpretation of a merit raise, basically robbing her of part of her deserved reward. “You’re looking at it,” the H.R. rep replied. Maureen protested formally, but the interpretation stuck, an excellent example of the power of TNTWWDIAH (That’s Not the Way We Do It Around Here).

INTERVIEW WITH AN AUTODIDACT

My employer has its own football team, its own police force, and its own nuclear reactor. Only a truly elite university has such a combination of business units, and I work for one of the most elite of all. Let’s just say you can smell salt water from my office.

I’m very fortunate to have the perfect job. I work with really smart people in scientific computing for a research institute supporting multiple universities. I work directly with the faculty, and I supervise doctoral candidates and post-docs, even though I myself don’t have any advanced degree.

But one thing I do have is the ability to teach myself whatever it is I need to know. Since we are developing new scientific software, there’s no such thing as a certification program for what we do. You have to figure it out as you go. It’s like running a marathon, with hurdles, only you have to build the hurdles yourself while you keep running.

Since I don’t have a Ph.D., you might say I’ve had to do a little extra to prove myself. And the faculty here can be very demanding. One of the things that has allowed me to stay ahead of them is that I am willing to slog through the fine print. They might glance at a tech manual or spec sheet, but I’ll read every word and double check every function. They don’t have the patience for that. My job is to create a bridge between something they invent and the scientists who will eventually use that product. A lot of times they don’t even know what it will do yet, and I have to commercialize it for release.

I’ve gotten four promotions and eight pay raises in just six years, which most people would consider impossible in a university setting. I earn six figures in an industry that is notorious for underpaying talent. Since I knew you were going to be calling, I’ve had time to think about how that came about. First of all, it was not an accident. Luck matters, sure, but my success was built on three things.

First of all, I am perfectly happy to be continually learning. A lot of people talk about continuing education, but I’m talking about continual education. I like it. It’s the opposite of hard for me. So this is the foundation of my success.

The walls of my success, to torture a metaphor, are hard work. I basically work if I am awake. I’m the go-to guy. I’m the guy you know will deliver.

And the roof of my success, the thing that keeps out the weather and protects what I have built, is my relationships with faculty. I live in a soft-money world. Projects form and dissolve, and so you are always looking for an assignment. If faculty know you and like you, this works out fine. But if you piss off the faculty, you get fired by not picking up a new assignment.

Here’s my career path: I got hired as a programmer analyst II, a nice hard-money assignment with security forever. The woman who hired me liked me. “Look,” she said, “You can’t get promoted in this unit. You’ve got to look around for something better.” It was great advice.

So with her blessing, I started interviewing all over campus, looking for something better. I picked up a PA III slot in another department, still hard money, still a job for life. The guy I supposedly worked for didn’t like to work very much, so I basically did his job for him. He was ROTJ [retired on the job], and I was emailing the department head in the middle of the night and responding to his job queries within a few minutes no matter when he pinged me. A cash-flow squeeze hit the whole university, and they actually gave my boss the axe. I did two jobs for a year before I got the promotion. That’s basically how you get promoted here: You do two jobs for awhile, and if you succeed, they’ll make it official. Eventually. So then I was a PA IV.

Then I switched over to the research institute as a PA V. The only way to get ahead, is to keep switching departments and extracting at least a 10 or 15 percent raise each time. You can’t get ahead on the seniority system. That’s for the ghouls, you know, the walking brain dead.

About this time I got called in by H.R., and they said, “You can’t have any more raises. Somehow you’ve already had more raises than are allowed by the system.” I said, “Well, is there any circumstance under which I might be allowed another raise before twelve months from now?” “Yes,” she said, “If you got a written offer from another employer, you might qualify for a retention adjustment.”

Well, thank you very much. Duh. So I put myself on the market, and got a written offer that I had no intention of accepting. I took it to my boss and said, “Hey, I like the university. I really like you guys. So, what can we do?” He got it approved, and that’s how I got my current grade. They had to make up a title for me. So I am a software scientist II. The only one in the system. It’s just a made-up title.

My advice? Three things: Get off your butt and learn what you need to know before anyone else does. Become known as a problem solver and, frankly, that means deliver the hard work. Slackers don’t advance very far. And make sure that lots of people know you’re a problem solver, not just the boss you have today but anyone who might be your boss in the future. Finally—and it took me some time to get how important this is—learn how to say no. Have a can-do attitude, but don’t be a yes man. When something’s not a winner, you have to learn to say, without whining, “No, I don’t want to do that. That’s not a good idea,” or “That’s not possible.” I don’t tell a boss what to do, really, but I lay out the options and help the manager make smarter decisions about work flow. Believe me, it is better to say no to something than to fail at it. Hard work, staying up with the learning, and being honest have worked pretty well for me.