I go but I return: I would I were

The pilot of the darkness and the dream

-Tennyson

With Alma so recently home from

the hospital, Hitchcock may not have been in the mood for the

rigors of promoting Vertigo. The cancer scare may have taken much

of the joy out of the prospect of showing his film to the media; on

the other hand, it may have provided a much-needed distraction.

Whatever mix of emotions Hitchcock had to deal with, this part of

the filmmaking process, the selling of the film, was one of the

most important parts-and one that a filmmaker neglected at his

peril.

As a young man, at a meeting of the Hate Club (a loose organization of filmmakers united by their dissatisfaction with the popular cinema of the time), he had created a stir by admitting that he made his films for the press. "The critics were the only ones who could give one freedom," he recalled, "direct the public what to see." They had all laughed at him then, but few of those Hate Club members were around to laugh at him by 1958. Hitchcock's success had vindicated his attitude. He had gained the freedom and power he wanted, in large part through his wise use of publicity. Over the course of his career, it was never so much a question of garnering good reviews-although they were important, and, for Hitchcock, usually in plentiful supply-as of cultivating the well placed feature story. Page after page of newspaper and magazine copy sold his films, his stars, and even himself as a director to the public. Hitchcock never ignored this aspect of the filmmaker's career; it was just as important as the filming itself-especially now that he had to compete against his own efforts on television. Why should people go out to the theater for a Hitchcock film when they could stay in and see one for free?

Selling Vertigo was a responsibility not to be ignored; as demanding as his personal life may have been, he would be in San Francisco for the film's premiere.

"Hitchcock designated San Francisco as the place to premiere it,"

Paramount publicity head Herb Steinberg recalled. "He designated

who he would like to have there for the opening, who would lend

most to the publicity of the film, and he also was very, very

helpful in the design of the advertising.

"When we finally had the premiere of the picture, we brought in newspaper people from all over the country to San Francisco. And among them were the syndicated columnists. We had coverage in most of the newspapers in the country and in some around the world."

Before the premiere, Paramount publicity released stories on the

film almost every week. Most were puff pieces on the stars, and

much was made of the supposed "feud" between Hitchcock and Novak.

In one release, Novak denied there was a feud, and she claimed she

was actually organizing a Hitchcock fan club on the set. Gossip

columnists dutifully picked up publicity-fed stories about roses

being delivered daily to Novak's dressing room from a mysterious

admirer (allegedly Cary Grant).

In April, The Hollywood

Reporter commented on an interesting gamble the filmmakers were

making: allocating a large chunk of their advertising budget to

college and high-school newspapers.

It is the first time any film

company ever has allocated such a ballyhoo sum ($10,000) for campus

media, completely distinct from magazines which have youth

readership. Paramount and Hitchcock are aiming at the broadening

film going market comprising teenagers. In making the school

newspapers' buy, Paramount is after a package deal. In one issue

appears the ad; in the subsequent issue appears a publicity plant

dealing with the picture; the two are tied into one

deal.

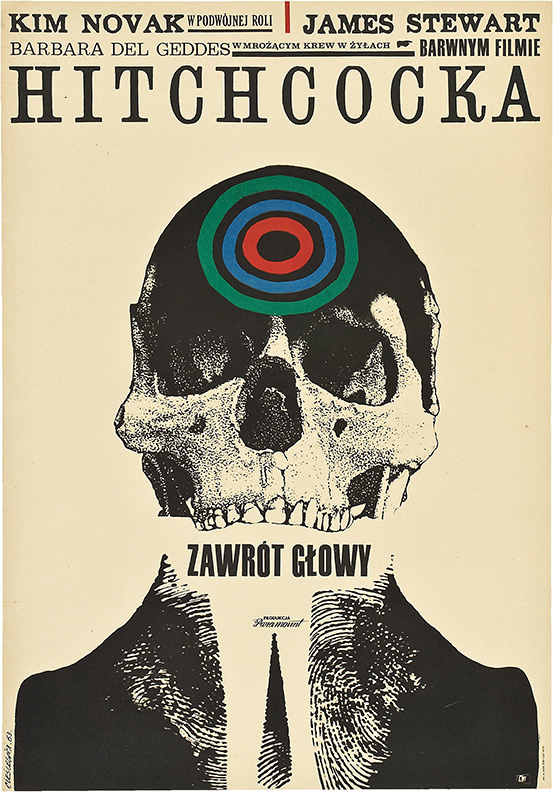

In addition to the school newspaper

campaign, full-color ads announcing the film appeared in Life,

Look, Seventeen, and Fan List. The ads alternated different tag

lines; most were built around conventional-looking images of the

stars, rather than on the Bass/Whitney poster graphic that has come

to represent the film to modern audiences.

Anticipating the more structured and

strict campaign for Psycho, ads for Vertigo flaunted the

storytelling strategy that had so recently threatened to disrupt

the production team: "When you have seen Vertigo, don't tell anyone

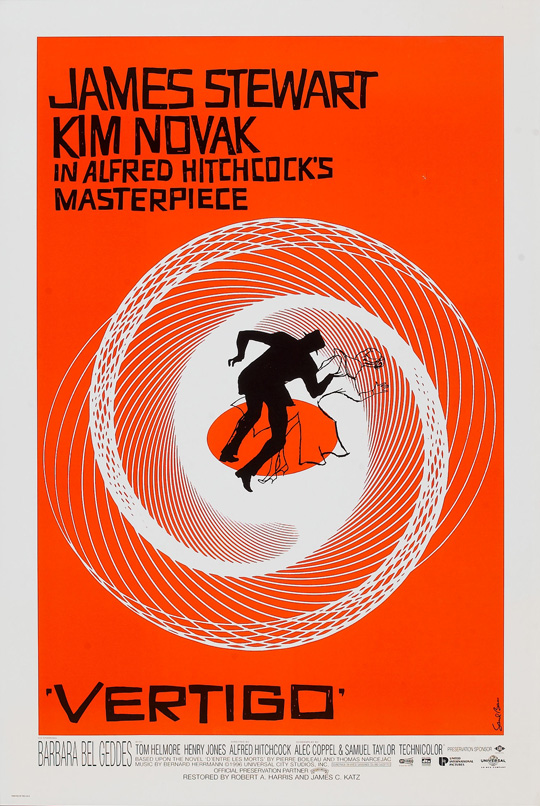

the great secret of the story!" Other ads used the Whitney spirals

as a motif: "Hitchcock creates a whirling, swirling vortex of

suspense," they declared. "Alfred Hitchcock engulfs you in a

whirlpool of terror and tension." In keeping with Paramount's high

expectations for the film, Saul Bass posters for Vertigo boldly

declared it "Alfred Hitchcock's Masterpiece."

TV spots also ran at the end of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and there were print ads in the director's mystery magazine. And there were other, more specialized promotions: Theater owners were encouraged to give roses to Novak lookalikes, and they were promised a single with Jay Livingstone and Ray Evans's Vertigo song (recorded by Billy Eckstine) on one side and Herrmann's "Prelude" and love theme from the sound track on the flip. No opportunity, it seemed, was left unexploited.

Hitchcock planned an elaborate press tour for the film's May ninth opening. Journalists mingled with the actors and Hitchcock at a cocktail party in the Clift Hotel (where all of the out-of-town journalists were put up) in the afternoon. The menu for the cocktail party was printed in French, a nod to the film's source material.

After cocktails, the party

moved to the Stage Door Theater, a 440-seat art house, for

Vertigo's first public showing; afterward, the journalists were

bussed to Ernie's for a late dinner. After a dinner of "La Noisette

de Boeuf Victoria avec Sauce Madere" and an appropriate wine,

die-hards were invited to the Venetian room at the Fairmont Hotel,

where Dorothy Shay entertained.

That was the official publicity. But

there was more, no doubt to Hitchcock's annoyance.

The very next morning, Kim Novak held a special press conference of

her own-the subject: a breaking scandal concerning her relationship

with a Dominican Republic official.

With unfortunate timing, Novak had managed to become involved in an

international incident on the eve of the film's premiere.

According to newspaper accounts at the time, she had been dating

Lt. Gen. Rafael Trujillo, Jr., son of the leader of the Dominican

Republic. During this relationship, she received several

high-priced gifts from the leader's son-including, allegedly, a

Mercedes-Benz. A columnist from the Los Angeles Times described the

morning:

Saturday I was rousted out of bed to attend the press

conference with Miss Novak-of whom I'd already been advised that

"Kim Novak's fondness for lavender will be fulfilled in her

beautiful suite at the Clift---lavender-scented, etc., etc." At the

conference, devoted to the now famous unlavender foreign car, gift

of Trujillo, Miss Novak looked unhappy. I have news for her-at

least one person in the room was unhappier than she.

Over Dick Williams's Monday-morning column in the Mirror-News ran

the headline KIM'S PEACEFUL WEEKEND SHATTERED. After describing the

lavish opening activities on Friday evening, Williams described the

next morning in some detail:

And on Saturday morning at 7 Am., a curious wire service

correspondent was banging noisily on the door of Kim's 13th floor

Clift hotel suite. She wanted to confirm the Trujillo gift

story.

But Kim's publicity girl wasn't buying any, thanks. No, Kim wasn't

talking. She was sleeping. Finally, she got rid of the reporter by

asking her to come back an hour later.

In the interim, the long distance wires were humming between the

suite and Hollywood headquarters and Kim hurriedly arose. It was

decided to hold a press conference at 10:30.

Kim looked very sharp in a red outfit at the conference and she

handled the questions reasonably well. Every time she got off the

party line, her publicist reminded her crisply, "Just a statement,

Kim, just a statement."

And when prying reporters kept boring in and wanting to know how

Kim thought that Mercedes-Benz was a temporary loan when she signed

the bill of sale, her representative just cut the whole thing off

and took her away.

It had been a busy year for Kim

Novak. While Hitchcock was in Jamaica, a storm of publicity

surrounded her alleged love affair with, and impending marriage to,

Sammy Davis, Jr. Harry Cohn was so shocked that he left a party in

New York and flew back to the studio to manage the crisis. Cohn

used everything in his power to end their relationship; he

threatened to fire Novak and use his influence to keep Davis from

working anywhere in Vegas, and the couple's relationship ended

almost immediately.

The Davis crisis may have been

too much for Cohn, who was seen taking nitroglycerin tablets for

his heart condition when he heard the news. He died of a heart

attack at the end of February.

While Novak was fending off the scandal-hungry press, another contingent of reporters was spending the morning on a tour of Vertigo locations with Hitchcock and Jimmy Stewart, who was just as committed to his own publicity as the director was to his. The junket included stops at Fort Point and Mission Dolores, where the mock headstone of Carlotta Valdes still rested in the cemetery (according to several locals, the headstone would remain there for several years).

The Los Angeles Times writer described the scene during the tours,

which had its share of technical problems:

At noon Hitch, who is partial

to travelogues, took us on a tour of the picture's location spots,

from a florist's to the Mission Dolores and the Presidio. We rode

in brand new cars (domestic), two of which broke down before we

reached the top of Nob Hill. Hitch had set up a fake slab for a

Vertigo scene in a quaintly picturesque cemetery adjoining the

mission. There was one tiny tombstone (real) that I can't forget.

It read, "Our Little Treasure-4 months and 16 days," and carried

the name of a baby girl who died more than a century ago.

Another Los Angeles paper reported on Hitchcock's interaction with

fans at the stops:

When our caravan stopped at the florist shop where a number of the

Vertigo scenes had been filmed, an elderly woman shoved her way

through the crowd to Hitchcock's side.

"Say Dearie, you look much better in person than you do on

television," she told him. Later, I asked Hitch how he liked the

publicity junket routine.

The pudgy little director shrugged his shoulders.

"You have to do it these days. It used to be that when you were

finished filming your work was done-you were home safe. But today,

you have to follow through. You have to go out and sell the picture

with stunts like this. So, I guess I'll have to get used to people

asking me how much money I make and telling me how I don't look

quite so bad in person."

But it was the Novak/Trujillo

story that garnered most of the headlines.

Monday morning's column about

the film mentioned the scandal prominently, and the news sections

devoted substantial space to the relationship between the actress

and the general's son. The scandal lay not in the mere fact of the

gifts-after all, Novak was no public official; it was hardly a

crime for her to receive presents-but, at just the moment Congress

was debating increasing aid to the Dominican Republic, reporters

and politicians found it reasonable to wonder where

the son of this tiny island nation's head of state was getting the

money to give away expensive imported cars.

The scandal persisted until the eve of the New York premiere at the end of May, when the younger Trujillo finally said farewell to Novak. Amid waning rumors of marriage, the lieutenant general returned to the army's school at Fort Leavenworth, and the affair was ended as swiftly as the Sammy Davis imbroglio had been.

Despite all the distraction, the film did garner mostly positive

notices from the local papers covering the premiere. One critic,

Jack Moffitt of The Hollywood Reporter, published a particularly

astute and prescient review on May twelfth:

Alfred Hitchcock tops his own

fabulous record for suspense. Aside from being big box office, it

is a picture no filmmaker should miss if only to observe the

pioneering techniques achieved by Hitchcock and his

co-workers....

The measure of a great director lies in his ability to inspire his

associates to rise above their usual competence and Hitchcock

exhibits absolute genius in doing this in Vertigo....

Stewart gives what I consider the finest performance of his career

as the detective. He portrays obsession to the point of mania

without the least bit of hamming or scenery chewing. Miss Novak has

become a fine actress.... Barbara Bel Geddes comes into her

own....

The skill with which Alec Coppel and Samuel Taylor constructed

their screenplay ... proves two things-l) that an audience will buy

any startling change in human behavior if you give it time (with

montages and subtle buildups) to believe the transitions and: 2)

that a murder mystery can be the greatest form of emotional drama

if one concentrates on the feelings of the characters rather than

the plot mathematics....

Vertigo is one of the most fascinating love stories ever

filmed.

Moffitt singled out the

contributions of most of the technical staff in this review, an

exceptionally detailed and perceptive piece of trade criticism. And

its tone was echoed by other organs: Film Daily's reviewer wrote

that "all in all, the picture is an artistic and entertainment

triumph," scoring the direction as "excellent" and the photography

as "tops." The Motion Picture Herald also rated the film as

"excellent." The Herald made special mention of Novak, saying that

the actress had found a "new plateau in her career through the

expert guidance of the 'master of suspense.'''

But there was dissent, even

from the beginning. Variety (5/14/58), which also predicted big box

office for the film, praised the locations and "Hitchcock's

directorial hand, cutting, angling and using a jillion gimmicks

with mastery." But the Variety critic qualified his praise with one

major complaint, the gist of which ran directly counter to

Moffitt's analysis in the Reporter:

Unfortunately, however, even

that mastery isn't enough to overcome one major fault, for plain

fact is that film's first half is too slow and too long. This may

be because Hitchcock became overly enamored with Frisco's

vertiginous beauty, and the Alec Coppel-Samuel Taylor screenplay

... just takes too long to get off the ground....

By [the film's climax] Vertigo is more than two hours old, and it's

questionable whether that much time should be devoted to what is

basically only a psychological murder mystery.

The reviewer concluded that the

film "looks like a winner at the box office," but he had settled

on an objection that would dog Vertigo's nationwide reception-its

languorous length and pace.

The word outside the trade

presses tended to follow Variety's lead. The Los Angeles newspapers

held their reviews until the film's general release at the end of

the month. In the May twenty-ninth Los Angeles Times, Philip K.

Scheuer sounded the tone that most popular critics would take with

the film:

VERTIGO INDUCES SAME IN WATCHER

Someone has described the latter-day Alfred Hitchcock film as a

thrillorama. This is as handy a way as any to sloganize Hitchcock's

Vertigo, which is part thriller and part panorama (of San

Francisco). Except for a few startling dramatic moments the scenery

has it....

In plot outline it is fascinating-Hitchcock has dabbled in a new,

for him, dimension: the dream-but he has taken too long to unfold

it.

The twice-told theme, hard to grasp at best, bogs down further in a

maze of detail; and the spectator experiences not only some of the

vertigo afflicting James Stewart, the hero, but also-and worse the

indifference. (Was Scheuer really characterizing Stewart's

character as "indifferent"?]

Blonde or brunette, Kim is not a remarkable actress, but she does

manage a creditable physical differentiation between Madeleine and

Judy. I was bothered by the fact that I could catch almost nothing

that Madeleine said (Stewart was guilty of some mumbling, too). I

had no trouble understanding the more raucous

Judy.

The Los Angeles Citizen-News

(5/29/58) concurred, but felt the picture had more serious problems

in the story department:

Unfortunately, the story, as

adapted for the screen comes off less praiseworthy, for most of the

time the picture is not a little confusing. The story line is not

easy to follow. ...

Vertigo is technically a topnotch film. Storywise, little can be

said. Hitchcock does as well as he can, considering the script, in

a directorial capacity. Vertigo is not his best picture.

Hazel Flynn, critic for the

Beverly Hills Citizen, characterized the film as "middling

Hitchcock." She wrote, "It has some extraordinary items in it but,

once the plot has begun to 'round, not even the director himself,

apparently, quite knew how to get off the treadmill." She added,

however, that even minor Hitchcock was "head and shoulders above

the photoplays of many other directors."

The reviews weren't all bad.

The Los Angeles Times’ main competitor, the

Los Angeles Examiner, found no fault in the film, although Ruth

Waterbury conceded that "you may feel it starts slowly

....”

She continued:

"There are two vivid stars in Vertigo, and both

of them are displayed at the top of their form. One is Kim Novak,

the actress, and the other is Alfred Hitchcock, the director. In

their quite different styles neither of them has ever been more

intriguing.... Vertigo may well make you dizzy, but it surely won't

bore you-if you like excitement, action, romance, glamor [sic] and

a crazy, off-beat love story."

Vertigo premiered in New York

at the Capitol the same weekend it opened in Los Angeles at the

Paramount. Sam Taylor remembers the screening-especially the

red-carpet treatment he received:

"This was in 1958, and when we

approached the Capitol we had to slow down to a crawl because there

were a lot of limousines in front of us, obviously with famous

people, and there was a whole crowd, naturally, of people who are

always at premieres with autograph books and

things.

"People would come out of the

limousines, there would be a great cheer, and they would be

attacked, and there was a red carpet. Finally our limousine drove

up in front of the Palace and the red carpet and the crowd of

autograph people surged forward and somebody opened the door for us

and one of the crowd stuck his head in and looked at us and said,

'Nobody!' So there you are."

Cue panned the film severely on

the thirty-first of May:

There was a time when Alfred

Hitchcock did nothing but turn out 70-80-90

minute movie masterpieces. They were taut, terrifying exercises in

suspense-manhunt melodramas, eerie tales of murder done and

detected, killings thwarted, dangers evaded, and horrifying flights

into the miasmic maze of disordered minds.

As director Hitchcock grew

more successful, his producers grew more generous. They put more

footage in his films, and greater production values. Hitch broke

the rhythm of his melodramas to make side excursions into scenic

beauties and romantic bypaths, elaborately dwelling on lavish

settings, costumes and similar appurtenances. He became entranced

by method rather than mood, style rather than substance, gimmicks

rather than grim melodramatics, and his pictures became elaborate

chess problems-in which frequently the beauty of the pieces rather

than their moves seemed to fascinate him.

Vertigo is a two-hours-and-eight-minutes case in point.

The New Yorker, whose review ran on June seventh, was equally

unimpressed. John McCarten summarized his review: "Alfred

Hitchcock, who produced and directed this thing, has never before

indulged in such farfetched nonsense." This same contempt was

echoed later by Time magazine's memorable label for the film:

"another Hitchcock and bull story."

But not all the East Coast coverage was bad. And the bad reviews

were, for the most part, attributable to the critics' confusion

over the admittedly complex plot.

Richard Griffith, in a June

seventeenth Los Angeles Times story headlined VERTIGO PLEASES NEW

YORK, wrote that the critics "don't want to spoil audience

enjoyment by tipping off any of the master's little surprises-but

since a Hitchcock film consists almost exclusively of said

surprises, there is little else for reviewers to say than see it

for yourself."

Griffith summarized the majority opinion on the film as "a treat

for all of his fans and for many who do not even know his

name."

Those involved in the making of

the film also found the finished product to be everything they had

expected. Taylor, who hadn't done much film work before Vertigo,

remembered being pleased by what he saw. "I thought the film was

very good and I was pleased with it. But I didn't go around saying

that I had just written a masterpiece or anything like that-and

neither did Hitchcock, for that matter; at least he didn't say so.

It was a normal reaction-1 thought, It's a good picture and I'm

pleased with it. As Hitchcock would say, 'It's just another

movie.'

"But I don't remember any

jumping up and down, and as a matter of fact, you know very well it

wasn't hailed with hosannas. I think a lot of people were puzzled

by it. It was just a Hitchcock picture that seemed to be a little

different for Hitchcock."

Herbert Coleman liked the film,

though, like many others on the Paramount team, he admitted that

it wasn't his favorite Hitchcock film: To Catch a Thief, doubtless

a more exotic filmmaking experience for those involved, remained

the close-knit group's favorite.

In a note to Hitchcock sent during the summer of 1958, animator

John Ferren praised the movie:

I liked Vertigo, both as a

picture and my sequence. I saw it twice. The first time I was put

out by some technical roughnesses, the second time I thought that

it had a real kick and was fine in and for the story. Incidentally

Bob Burks photographed the thing (I mean the entire picture)

beautifully. My home town never looked so good.... My feet are clay

enough to have enjoyed seeing my screen credit up there bigger

than life.

Saul Bass, who later won an award for his design work on Vertigo, wrote to Hitchcock after the film's release:

"I'd like to take this

opportunity to thank you for providing me a framework within which

I could produce something of worth. I do hope I may have the

opportunity to work with you again."

If grosses are any indication of success, Vertigo was neither winner nor loser. It finished twenty-first in 1958 ticket sales, with $3.2 million-the equivalent of approximately $7 million in 1997 dollars. This was about $2 million off what Hitchcock had made on Rear Window ($5.3 million) and what he would take in on North by Northwest ($5.5 million), but better than The Wrong Man-a ranking that accurately reflected each film's relative commercial nature.

The 1958 figure does not account for overseas sales. The final cost

of making Vertigo ran to $2,479,000-which means it garnered

something like $1 million in domestic box-office profit on its

first outing. Of the final price, Paramount picked up

$2,004,722.49 and Hitchcock Productions paid $443,307. None of

these figures include Hitchcock's or Stewart's salaries, which were

based on an undisclosed percentage of the film's

grosses.

The real money was in the ownership of the film. Hitchcock's contract gave Paramount an eight-year lease on five of the films, after which the rights would revert to Hitchcock. Paramount re-released Vertigo and Rear Window in 1963 to playoff the release of The Birds, but no figures are available for this second run. There was another release after the rights reverted to Hitchcock in the late sixties, through Universal, and then a sale to television. After the early seventies, the film was pulled from release, along with the other Paramount films Hitchcock owned (The Trouble with Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Rope, which Hitchcock had financed through his own short-lived company, Transatlantic Pictures). Psycho, Hitchcock's last Paramount film, was sold to Universal in 1968, when the rights returned to Hitchcock.

Vertigo had very limited availability in the early seventies, and

then disappeared completely from distribution in 1974. Why? There

was no compelling legal or financial reason. According to Herman

Citron, Hitchcock's agent, the decision was personal. Hitchcock

refused inquiries from colleges and film societies that requested

it for screenings. He wasn't so restrictive with the other titles

(two of which he donated in 16mm reductions to a prominent eastern

university), but with Vertigo, he was far more

protective.

If Hitchcock's intention was to set aside a nest egg for his family

by keeping Vertigo and the other films off the market, the decision

was wise. The director's career may have been on the wane in the

sixties and seventies-certainly his last great film was Mamie,

which has deeply divided critics over the years-but his critical

reputation was approaching its zenith.

There is an odd parallel between the period of the director's

critical rise and the decline of his new work. In 1958, Hitchcock

was an economically successful director. His pictures turned

profits and his personal recognition skyrocketed with his popular

television series.

But despite his artistic

pretenses as a young director in England, Hitchcock was never

considered a "serious" filmmaker by American critics. When their

personalities lent themselves to the enterprise, directors like

Hitchcock were used as advertising labels for films, but that was

as far as the auteur theory went in America's consciousness: There

simply was no serious domestic critical community available to

celebrate cinematic artists.

Nineteen fifty-eight, though, was a turning point for both

Hitchcock and art cinema. In France, Claude Chabrol and Eric Rohmer

had published in 1957 the first book-length critical assessment of

Hitchcock-Hitchcock: Classiques du Cinema. The book ended with The

Wrong Man (what a difference a few years would have made); though

it was unavailable in English until the late sixties (Hitchcock:

The First Forty-four Films, translated by Stanley Hochman) their

work was extremely influential.

One of Chabrol and Rohmer's

fellow filmmakers, Françoise Truffaut, was also a Hitchcock

admirer. After a brief meeting with Hitchcock during one of the

master's visits to France, Truffaut proposed conducting a series of

interviews to discuss the genesis of all of Hitchcock's films. The

celebrated Hitchcock/Truffaut interviews (comprising fifty hours in

all) began during the postproduction of The Birds and the start of

production on Mamie. Published in book form-first in France in

1966, then in 1968 in the United States-the interviews treated

Hitchcock's career with a sense of continuity and purpose, with

Truffaut insightfully tracing recurring themes and establishing

core films (The Lodger, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Shadow of a

Doubt, Notorious, Rear Window).

Surprisingly, both directors

had remarkably little to say about Vertigo.

Hitchcock acknowledged defects

within the picture, and he groused slightly about Novak's

performance (over which Truffaut enthused). The overall impression

that Hitchcock gave was that Vertigo had failed him. But Hitchcock

the auteur of 1962 was the same man who had worried over the

box-office receipts for The Wrong Man just before mounting

Vertigo-indeed, the same man who had shocked the Hate Club decades

before with his pledge of allegiance to the critics-and he remained

quick to criticize films that offered no box-office or critical

satisfaction. After all, what other judgment was there to trust? To

the entertainer, the audience and the critics have the final say:

No matter how secure one may feel in a performance, it's the level

of applause that determines success.

But years after the mixture of

applause and complaint that greeted Vertigo had died down;

Hitchcock's most personal film began to attract an extraordinary

level of renewed critical interest. Among several books written

during the director's last years that examined the Hitchcock canon,

by far the most important---both in general and in the special

attention it paid to Vertigo-was Robin Wood's Hitchcock's Films

(1965).

Wood began his analysis with a fundamental question: "Why should we take Hitchcock seriously?" His response made well-reasoned comparisons to another great English entertainer: William Shakespeare. Wood argued that Hitchcock's films showed a "consistent development, deepening and clarification," that there was an overall unity to his work that transcended the merits of each individual film.

"But within this unity-and this

is something which rarely receives the emphasis it deserves-another

mark of Hitchcock's stature is the amazing variety of his work ...

consider merely Hitchcock's last five films, made within a period

of seven years, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds,

Marnie .... True, he never invents

his own plots, but adapts the work of others: again, one cannot

resist invoking Shakespeare. Hitchcock is no more limited by his

sources than Shakespeare was by his. The process whereby Greene's

romance Pandosto was transformed into the great poetic drama of The

Winter's Tale is not unlike that whereby Boileau and Narcejac's

D'Entre les Morts became Vertigo: there is the same kind of

relationship.... Shakespeare's poetry is not an adornment for

Greene's plot, but a true medium, a means of absorbing that plot

into an organic dramatic-poetic structure; precisely the same is

true of Hitchcock's mise-en-scène in Vertigo."

But it was a later pronouncement in Wood's book that led to the reawakening of interest in Vertigo in the seventies and eighties: "Vertigo seems to me Hitchcock's masterpiece to date, and one of the four or five most profound and beautiful films the cinema has yet given us."

He supports this large claim by

examining the film's treatment of themes "of the most fundamental

human significance." And, like its creator, Wood spends

considerable time debating the significance and reasoning behind

the decision to include Judy's confession two-thirds of the way

through the film. "Our immediate reaction to the revelation, I

think, is extreme disappointment. This can exist on a purely

superficial level: we have come to see a mystery story and now we

know it all, so what is the use of the film's continuing? Why

should we have to watch the detective laboriously discovering

things we know already? Much popular discontent with the film can

be traced to this premature revelation, and in terms of audience

reaction it was certainly a daring move on Hitchcock's part."

Vertigo, according to Wood, ultimately represents the world as

"quicksand, unstable, constantly shifting ... into which we may

sink at any step in any direction, illusion and reality constantly

ambiguous, even interchangeable."

He concludes that

Vertigo "seems to me of all Hitchcock's

films the one nearest to perfection. Indeed, its profundity is

inseparable from the perfection of form: it is a perfect organism,

each character, each sequence, each image, illuminating every

other. Form and technique here become the perfect expression of

concerns both deep and universal. Hitchcock uses audience

involvement as an essential aspect of the film's significance.

Together with its deeply disturbing attitude to life goes a strong

feeling for the value of human relationships.... Hitchcock is

concerned with impulses that lie deeper than individual psychology,

that are inherent in the human condition.... In complexity and

subtlety, in emotional depth, in its power to disturb, in the

centrality of its concerns, Vertigo can as well as any film be

taken to represent the cinema's claims to be treated with the

respect accorded to the longer established art forms."

It was this kind of evaluation

that increased public demand for the film just as Hitchcock was

tucking it away for more than a decade. Wood's book was followed by

others, including Donald Spoto's The Art of Alfred Hitchcock

(1976), more of a layman's approach to the master's films. Spoto

agreed with Wood in his assessment of Vertigo, but by the time his

book was published, the film was gone-which only added to its

allure. The film that once had drawn audiences only slowly to

neighborhood theaters was now hoarded jealously in clandestine

prints held by fans and collectors; these prints ranged from the

good (pristine IB Technicolor 35mm or 16mm reductions) to the awful

(including black-and-white versions and primitive video

dupes).

Since the film returned to the

screen-at first as a part of a major 1984 Hitchcock rerelease

program, then in the glorious 1996 restoration-Vertigo has served

as mirror to the critical perspectives of our time: feminist,

Marxist, and deconstructivist critics regularly issue new readings

of its meaning, while others offer close readings that sketch

Hitchcock the filmmaker as Svengali, as necrophiliac, even as

confused loner.

Even the quality and place of Vertigo in the canon is still hotly debated.

There are still academics who see the film, with its narrative and

structural weaknesses and its occasional technical shortcomings, as

a failure; but the majority opinion places the film among

Hitchcock's most important, and often at the top of the list-and

maintains, moreover, that it is the key to understanding Hitchcock,

the artist and the man. Are the original creators surprised at the

renewed interest in Vertigo? Herbert Coleman is not surprised at

Hitchcock's popularity, but he is bemused by the attention lavished

on this film. For Coleman and other crew members, it was just

another Hitchcock project.

Sam Taylor is pleased that

after so many years the film has a following. "I am very proud. Not

surprised, because it does have the depth that is fairly unusual

for a picture of that sort. I watch with a great deal of pleasure

the growth of the legend of Vertigo."

Novak still sees the film as a

very personal one for herself and Hitchcock. "It was almost as if

Hitchcock was Elster, the man who was telling me to play a role ...

here's what I had to do, and wear, and it was so much of me playing

Madeleine ... but I really appreciated it. In hindsight, I think

he's one of the few directors who allowed me the most freedom as an

actress. That might seem hard to believe because he was so

restrictive about what he wanted. But even though he knew where he

wanted you to be, he didn't want to take away how you got to that

point. He wouldn't tell me what to be thinking to get to a point.

Today, I'm very proud of Vertigo because I do think it's one of the

best things I've ever done."

For Stewart it was the character's fear that still resonated with

him.

That, and Hitchcock's own personal involvement. "After several years, I saw the film again and thought it was a fine picture. I myself had known fear like that, and I'd known people paralyzed by fear. It's a very powerful thing to be almost engulfed by that kind of fear. I didn't realize when I was preparing for the role what an impact it would have, but it's an extraordinary achievement by Hitch. And I could tell it was a very personal film even while he was making it."

Hitchcock never matched the zenith of the period that ran from Rear Window through Mamie (and many would contend that that film is a disaster). His films of the late sixties, Tom Curtain and Topaz, were weak; only the last two Hitchcock films, Frenzy and Family Plot, showed anything like the special quality that marked his finest work.

By the 1970s, time had caught up with Alfred Hitchcock. He was an artist who had never planned to retire-yet, though he went through the motions of writing a new script, it was clear to everyone around him that his filmmaking days were over. His confidante, friend, and co-creator, Alma, had suffered a series of strokes. Letters he wrote during the period reveal the director in his final role: as a husband caring dutifully for an ailing wife. Given his concern for and attachment to Alma, it is doubtful that even Hitchcock himself entertained any serious notion of shooting another film after Family Plot in 1976. Planning and writing had always been Hitchcock's great pleasure-he often said that after finishing a script he dreaded having to go on and commit it to the screen, for the film was already complete and perfect in his mind. Yet he surely missed the days of total involvement in crafting challenging shots with a well-tuned crew.

After much lionizing in the final years of his life-months before his death, he was awarded a knighthood-Sir Alfred Hitchcock died at his home in Bel Air in April 1980, certainly aware that his reputation was intact with the only audience that counted: posterity.

The death of Hitchcock marks the passage from one era to another. I believe we are entering an era defined by the suspension of the visual. I don't think we'll have the strength to make cinema much longer. Jean-Luc Godard

Allusions to Vertigo, in today's culture of cinema, music, and television, pop up everywhere. Certainly many are unintentional-after all, every murder mystery features scenes of detectives following their objects of pursuit-but just as many are by way of intentional and direct homage to the film. Even before its initial release, Kim Novak and James Stewart had their lives affected by Vertigo, choosing for their next project a story that profited directly from the mysterious atmosphere Hitchcock created around them. Bell, Book and Candle comes nowhere near the sophistication of Vertigo, but its proximity to the film in release date, and its vague thematic similarities-Stewart is bewitched again by Novak-often confuse moviegoers.

Hitchcock reworked the themes and daring construction of Vertigo in his last film for Paramount, Psycho. Norman Bates, too, suffers from an obsession-his after the death of his mother though, in his case, of a far more deadly variety: Unable to accept her death (due to his own actions, just as Scottie felt that his inaction had led to Madeleine's death), he develops a psychological problem far more complex and unhealthy than Scottie's. Rather than remaking women into his mother, he keeps his dead mother preserved and kills off any woman who threatens her dubious reality.

Hitchcock's daring strokes in the construction of Psycho overshadowed the groundwork he had laid in Vertigo. Killing off the story's lead actress in the film's first half hour had its own disorienting effect on 1960 audiences. The effort to keep audiences from revealing the "surprise" (as the advertising campaign had attempted for Vertigo) was doubled.

The Psycho ad campaign was built on the premise that no one would

be seated after the film started. Hitchcock made a special film for

the distributors of Psycho, explaining the policy and why it should

be enforced. Pinkerton guards were hired for the major theaters in

New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles to assist in enforcing the "no

late seating" policy. And, in the end, what had had a questionable

effect on Vertigo ticket sales was a major success with Psycho:

The film earned more than $8 million in its first release.

Psycho came at an important moment for Hitchcock. The last of his

Paramount films would also be his final unquestioned box-office

winner, and his work seemed to grow more impersonal as that of

younger filmmakers grew more personal. But Vertigo, if not in its

first release, then certainly in its 1963 rerelease, began to have

a slow and methodical influence on the very artists whose

success-whose power and freedom-Hitchcock envied.

Hitchcock stood in a unique position to these filmmakers: His films

influenced the experimental and independent filmmakers more

profoundly than the work of any other major studio director. Psycho

certainly revolutionized the horror genre and the production

process, proving to the studios that a very profitable film could

be made for under a million dollars. The studios for the most part

ignored the lesson, but the sixties saw an enormous growth in small

production companies whose sole purpose was to turn out low-budget

horror fare.

In the four decades since its initial release, the generation of

moviemakers who grew up on Hitchcock and 'Vertigo has grown into

maturity. And as a result much of the director's work finds its way

into popular films by way of allusion-through either images or

film construction that owes a debt to the Master's style. The

director himself seemed not to mind this homage, no matter how

absurd: When Vertigo turned up as the focus of Mel Brooks's 1977

Hitchcock parody, High Anxiety, Hitchcock himself wrote Brooks a

complimentary note and sent a case of expensive Bordeaux wine as a

gift.

Other than the obvious spoofery of High Anxiety, the most overt absorption of Vertigo is in Brian DePalma's 1976 Obsession. But that film is less an extension of Hitchcock's work than, quite simply, a mess. It exhibits none of the structural bravery of Hitchcock's film; worse yet, the very thing that makes Vertigo work-our uncomfortable identification with its lead character-is missing. DePalma's film never gives us the opportunity to share Cliff Robertson's feelings for his lost wife, who dies in the film's first twenty minutes; what's left is not an engaging mystery-despite its provocative Bernard Herrmann score-but a series of long scenes of pursuit without any momentum behind them. DePalma later reworked Vertigo in a tawdry enterprise that mixed it with Rear Window in a prurient blend, but Body Double, intended as an angry assault on DePalma's critics, never generated the kind of interest the director had hoped for.

There are better filmmakers whose work owes much to Vertigo. Martin

Scorsese, for all the differences between his typical subject

matter and Hitchcock's, has done far more to earn comparisons with

the director of Vertigo and Psycho. Few other filmmakers have taken

the kind of risks Scorsese has. The obsession of De Niro's taxi

driver in the film of the same name is the dark portrait of a

working-class Scottie in a world far more nightmarish than

Hitchcock ever imagined-a connection assisted by Herrmann's last,

truly great score.

Certainly Scorsese's lushly romantic 1993 film, The Age of

Innocence, owes much to Vertigo. Think of the lingering camerawork

over the flowers in the title sequence, designed by Saul and Elaine

Bass; the attention to art and the past; the passionate obsession

of the male character with a forbidden woman; the psychological

breakdown of that character under the grip of social standards.

Vertigo echoes in this film's every frame. The real value of a

great work of art is reflected less surely in the necessary evil

of imitation (think of the poor imitations of Shakespeare's plays

pulled together by competing theaters) than in how the work

influences other artists as they add their own creations to the

dialogue. Martin Scorsese is an excellent example of the artist as

synthesizer-as, for that matter, was Alfred

Hitchcock.

Hitchcock liked to portray

himself as the uninfluenced artist, but he screened movies weekly,

sometimes daily, during the months he spent between projects. Ken

Mogg, editor of the Hitchcock publication The MaeGuffin Journal,

has done brilliant work in linking Vertigo with possible

predecessors: the two versions of Le Grand Jeu (1934 and 1953);

Carrefour (1938); The Uninvited (1944); Portrait of Jennie (1948);

and even I Remember Mama (1948, costarring Barbara Bel Geddes and

set in San Francisco)-all bear signs of having made strong

impressions on Hitchcock.

Among the recent wave of

independent filmmakers (and Vertigo, despite its development at

Paramount, was almost an independent film in both conception and

execution), there are many directors who come to mind as keepers of

the flame. Gus Van Sant, the director of My Own Private Idaho and

Mala Noche, has done thought-provoking work within the obsession

genre that Hitchcock helped create. His imagery and rich colors

evoke the sensuality of colors that the restored Vertigo reveals.

Danish director Lars von Trier's Zentropa is a stunning film that

appears to owe much of its imagery to Vertigo. Von Trier uses

transparencies in a stylish and imaginative way, and the film's

spiraling images lead the viewer into the fractured world of

postwar Germany in much the way they led Vertigo's audience into

Scottie Ferguson's twisted inner world.

And Vertigo's influence has

extended in other directions besides the thematic. Often called

"the filmmaker's film," over the years it has had a special

influence on experimental filmmakers. Director Chris Marker was

certainly affected by the film: His groundbreaking La Jetee (1964)

is suffused with direct allusion. The twenty-nine-minute film tells

the story through still photographs of a man who's obsessed by an

image from his youth. When he meets the woman central to the image,

they visit a Parisian garden. "They stop by a tree trunk with

historic dates," the narrator tells the viewer. Then, "as if in a

dream, he points beyond the tree and hears himself saying: That is

where I came from ....” Vertigo was also an explicit part of

Marker's film Sans Soleil (1982). Sans Soleil has a complicated

narrative that moves all over the world, but a memorable sequence

intercuts scenes from Vertigo with a visit to San

Francisco.

Chris Marker recently wrote an

interesting homage to Vertigo for Projections: "The power of this

once ignored film has become commonplace," Marker wrote. "'You're

my second chance!' cries Scottie as he drags Judy up the stairs of

the tower. No one now wants to interpret these words in their

superficial sense, meaning his vertigo has been conquered. It's

about reliving a moment lost in the past, about bringing it back to

life only to lose it again. One does not resurrect the dead; one

doesn't look back at Eurydice. Scottie experiences the greatest joy

a man can imagine, a second life, in exchange for the greatest

tragedy, a second death."

Marker described his first

experience with Hitchcock's film; "I saw Vertigo as it was shown in

France. I could hardly tell the year, but the rule in those times

was approximately one year after the US release, so we can say

1958/60. The impact was immediate and didn't cease, even though I

deepened my understanding at each new screening. But the emotion

was and still is intact. When they presented part of the trailer on

TV to announce the 1996 release of the 70mm version, seeing Novak

in the green light of the room after her final transformation gave

me the same goose flesh as ever."

There is "something of Vertigo"

in a CD-ROM Marker is currently creating, entitled Immemory. "I use

as the gatekeepers of the Memory sequence the two gentlemen who

[made] the best use of the name "Madeleine," Mr. Alfred Hitchcock

and Mr. Marcel Proust. It is through a digitized Novak the user

will gain access to different layers of my Memory

machine."

Vertigo has also inspired

artists outside of the medium. Much of this work was recently

recognized in an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in

Los Angeles. "Art and Film Since 1945; Hall of Mirrors" called

attention to artwork connected to many of Hitchcock's films, most

notably Spellbound, Rear Window, Psycho, and Vertigo. The exhibit

included both art used in Vertigo and art inspired by the film;

featured in the exhibit are the opening titles by Saul Bass and

John Whitney, Marker's La Jetee, and other works that pay homage to

Hitchcock's vision.

Cindy Bernard's photographic

work is perhaps the most straightforward in the exhibit, yet

startling on its own terms. In the series entitled Ask the Dust,

Bernard revisited a group of famous film locations to shoot

pictures using the same lenses and camera positions as the

original films. The results are haunting-the locations are

recaptured not as we know them, but like ghost landscapes, without

actors or the context of a theater to animate them. Of the

twenty-one films that Bernard selected, two were Hitchcock's: North

by Northwest (for which she chose the site of the famous

crop-duster scene) and vertigo, for which she selected the view of

the Golden Gate Bridge from Fort Point. "As an object or film,"

Bernard has said, "vertigo is beautiful, an amazing piece, just on

that level."

When she originally conceived

the project in 1987, Bernard chose as her cultural window the

twenty years between 1954's Brown v. Board of Education decision

and Richard Nixon's 1974 resignation. "The films that I included

either fit the idea-that of landscape and the effect that film has

had in defining the landscape for us-[or were] films that I loved

and wanted to include."

Vertigo fell neatly into both

categories, although Bernard admitted that the fit didn't appear

natural at first. But nevertheless, she was drawn to the film: "I

think it was the depiction of impossible memory-Scottie's inability

to let go, [his desire] to re-create the space of that experience,

to create a simulacra of Madeleine. This was very powerful to me.

I also think the attraction has to do with the film as a metaphor

of the artistic process: Scottie's obsessive desire to make this

thing/woman what it is he wants her to be."

Bernard's work demonstrates the

power of location to evoke the memory of a film-perhaps most

provocatively with vertigo, a film itself concerned with the power

of memory, and a film so linked to its location that it has

inspired decades of pilgrimage.

Indeed, it's difficult to think

of another film that has inspired this kind of devotion. Harrison

Engle, the director of Obsessed with Vertigo, AMC's

excellent documentary on the making and restoration of the film,

may have been one of the first pilgrims to visit the Bay Area

specifically to observe the locations from the film. The young

Midwesterner was on a school trip to the West Coast in June of

1958-no more than a few weeks after Vertigo's

release-when he went on his own to visit the San Francisco sites.

"The film was mesmerizing and deeply affecting the moment I saw

it," he says. "It touched that part in me that we all feel-that

wants us to hold on to the past."

Chris Marker recalled his own

visits to the locations: "My first move was to do something

relatively original at the time, very common today: revisiting all

the locations, doing the 'Vertigo tour.' I did it again a few

times, and especially in 1982 to shoot the footage for Sans Soleil.

You won't be surprised to hear that when I relaxed at the little

coffee shop on the San Juan Bautista plaza, the cookie on my plate

was in the shape of a spiral," Marker remembered. He went on to

note that "utopia" for him meant renting the apartment at 900

Lombard Street, which he did during his 1982

stay.

Over the years a number of

articles have been published describing Vertigo tours; in fact, a

map was recently published, listing the film's locations (among

other Bay Area film locations). This author's own pilgrimage in

1986 was overwhelming in its effect: The work of Cindy Bernard may

come closer to conveying the power those locations hold than words

can.

Remembered lines and music were

an important part of Christian Marclay's contribution to the MoCA

exhibition. Using elements from Vertigo's dialogue and score,

Marclay's installation, Vertigo (soundtrack for an exhibition),

plays snippets from the film at random lengths and at random

intervals. The installation was described as a "new soundtrack"

that "startles the unaware gallery visitor, conjures up iconic

images from the film, but then creates from them a new film of the

imagination."

Marclay, a sculptor and "sonic"

artist, originally composed the installation for a 1990 Paris

exhibition entitled ''Vertigo''-an exhibition that had nothing

explicitly to do with the film, though Marclay points out that this

particular curator had a penchant for using Hitchcock films as

titles for his exhibitions. "This installation was not meant to be

ambient music," Marclay explained. "The volume is meant to be loud

so that the museum or gallery visitor is startled and not allowed

to ignore it. I took the film's soundtrack as raw material to work

with-both the dialogue and the music. Once the dialogue or the

music is pulled out of context, the abstract lines take on a

significance that I didn't notice in the film.

"There are many moments in the film though where image and sound

cannot be separated, where the two have become so connected in

almost a cliché way that the music summons the image and the image

summons the music.”

Vertigo's unique appeal continues to draw artists and audiences back into the darkness of the theater to experience the wrenching obsession and loss that it conveys so deeply. Who would have ever imagined in 1958 that such a dark, unlikely story would have so much to say to audiences forty years later? No surprise, then, the comparisons between Hitchcock and Shakespeare-two masters skilled at selling such misery to a willing audience.