3

NOTHING UNSAID

GUBBIO IS A BEAUTIFUL MEDIEVAL TOWN, STRATEGICALLY LOCATED ON THE SLOPE OF A STEEP HILL, ABOUT FIFTY MILES SOUTH OF URBINO, THEN THE CAPITAL OF THE MONTEFELTRO TERRITORY. Federico da Montefeltro was born in Gubbio in 1422, a bastard son of the local lord, Guidantonio. Federico’s son Guidobaldo was also born here in January 1472, when his father had just turned fifty. Before then, Federico’s wife, Battista Sforza (distantly related to the Sforza of Milan), had given birth to four daughters, who—because of their sex—were ineligible as heirs. Six months after delivering the eagerly expected male heir, upon her husband’s return from the war against Volterra, Battista suddenly died (probably weakened by too many pregnancies), leaving Federico a widower and Guidobaldo an orphan.

In their native town, Federico built a stunning ducal palace in which he commissioned a studiolo (its gorgeous inlaid wood panels are now preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). The Gubbio studiolo mirrored Federico’s refined taste in art and culture. As a teenager, Federico went to one of the best schools, the Cà Zoiosa, or Joyous House, an elite institution just outside Mantua. (Other students included Ludovico Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, and Mantuan ambassador Zaccaria Saggi.) Classical authors from Greek and Latin antiquity were taught by the famous humanist Vittorino da Feltre. There was also serious martial and athletic training. It is no surprise that Federico took seriously the education of his son, who embodied the living hope of survival for his long-term plans. He hired the best teachers and bought the best books. And in the Gubbio studiolo Guidobaldo’s name was to be inscribed next to an open page of Virgil’s Aeneid:

Every man’s last day is fixed.

Lifetimes are brief and not to be regained,

For all mankind. But by their deeds to make

Their fame last: that is labor for the brave.

“DANGEROUS DANGERS”

ON JULY 2, 1477, IT MUST HAVE BEEN HOT IN THE GUBBIO studiolo; only the slight summer breeze coming through the window would have made the inside temperature more bearable. Here Federico da Montefeltro could gaze upon the surrounding walls’ trompe-l’oeil images, in the most elaborate inlaid wood, of objects that looked so real one could have reached out and touched them: shelves, books on lecterns, musical and scientific instruments, weapons and pieces of armor, all arranged in a disorderly fashion. These were the objects that befitted the humanist soldier Federico when he needed solitude or contemplation.

The gold lettering (possibly dictated in Latin by Federico himself) that ran along the top of the studiolo’s paneling read as follows:

You see how the eternal students of the Venerable Mother

Men exalted in learning and in genius

Fall forward in supplication with bared head and bended knee

The original panels of the Gubbio studiolo are now preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The original panels of the Gubbio studiolo are now preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Paintings representing the seven liberal arts encircled the upper walls in an encyclopedic homage to the duke’s erudition. Each of the arts, embodied by an allegorical female figure, handed her precious gifts to a powerful, bareheaded male figure. From the corner of his left eye, Federico could catch a glimpse of his own portrait, in which he was shown kneeling, his red-felt hat resting on the elegantly carpeted steps. Just above him in the picture, a shield with the Montefeltro coat of arms held by the imperious Montefeltro eagle surmounted a metal sconce. To the right of the figure, a painted window frame opened onto a room with an open door, the traditional symbol of the gateway to knowledge.

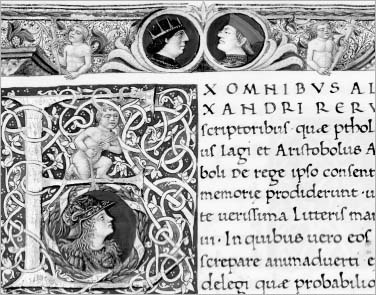

Portraits of Ferrante of Aragon (left) and of Federico da Montefeltro (right), decorating the top border of a manuscript about the life of Alexander the Great.

Portraits of Ferrante of Aragon (left) and of Federico da Montefeltro (right), decorating the top border of a manuscript about the life of Alexander the Great.

Federico is seen being offered a thick volume by a woman, the allegorical figure of Dialectic, one of the liberal arts. Dialectic, or logic, is the queen of the trivium, which lays the foundation of language and thought, along with grammar and rhetoric, the two sister liberal arts as codified in antiquity. The book Federico receives has a golden clasp and is decorated with an image of the nude Hercules. The depiction emphasizes the strength of his logical reasoning, the stringency of his mental acuity as much as of his military action.

That morning, preparing for dictation, Federico undoubtedly summoned his secretary, who would have bowed respectfully and taken a seat at a little desk next to him. The duke’s letter to Cicco Simonetta, his old friend and now the all-powerful regent of the Milanese duchy, begins this way:

Through letters sent from Milan I have been informed how trustingly and lovingly Magnificent Messer Cicco and his son Messer Gian Giacomo have conveyed the news of the events occurring up north, and most importantly all the reasons why they do not want to come to any agreement or intelligence with His Majesty the King of Naples. I am pleased and satisfied that Their Magnificences behave towards me with the faith and sincerity that I deserve for my devotion and fidelity to Duchess Bona and Duke Gian Galeazzo and the affection I have for Their Magnificences, whom I confess to revere as much as I am obliged to the welfare and honor of His Majesty the King of Naples. However, if I thought I was speaking against conscience and truth and the need of the Milanese state or Their welfare, I would rather be silent and would not talk at such length as I have, without any regard to my special interest. Nevertheless, I am only judging what is good and honorable for both parties, and mostly for the one that is in the most dire need…

Since January 1477 Cicco and Federico had been corresponding in cipher. The Milanese chancellor had first called Federico to Milan to help him stabilize the duchy. Federico had responded enthusiastically, but Lorenzo’s intervention had prevented him from coming. Now that Cicco Simonetta (addressed as “Magnificent,” as was customary in Renaissance diplomatic jargon) had assumed the role of guardian to the fatherless Gian Galeazzo, the Milanese state was indeed “in the most dire need” of external support, as Federico pointed out in his letter.

By now, halfway into 1477 and six months after the Duke of Milan’s assassination, Italian politics were at a delicate juncture. With the general league, or alliance, among Venice, Milan, and Florence becoming weaker in the face of the united front formed by the King of Naples and Pope Sixtus IV, the Duke of Urbino, serving as a mercenary captain to both of the latter powers, wished to be at the center of any decisive intelligence in Italy. If only he could persuade the Milanese regent to switch sides, the ensuing isolation of Florence would allow him and his patrons to put enormous pressure on the Medici brothers, Lorenzo and Giuliano. They would be able to kick those two rich and influential youngsters out of Florence—violently or otherwise—and replace them with a more complacent set of rulers. The Duke of Urbino was laying the groundwork for what would become the Pazzi conspiracy, well ahead of its actual execution.

Perhaps Federico took a deep breath and paused before resuming his dictation. He may have looked at the painted panel on his left: it depicted an older woman holding an armillary sphere, which she was handing to a middle-aged man kneeling before her. His jeweled crown shone on the steps. The man thus represented here as Ptolemy was Federico’s close ally and protector Ferrante of Aragon, King of Naples, who was known to have a great passion for astronomy, which in this era was almost identical to astrology. The Ptolemaic king embodied the higher powers, the heavenly realm above Italy. But on the panel, he was placed next to the matching portrait of the Herculean captain Federico, who partook of the earthly realm.

Astrology and politics were closely linked during the Renaissance. Even the fate of these proud self-made men was seen as being tied to the inescapable influence of the stars. An emerging sense of the significance of the individual did not prevent the most learned and active figures of the fifteenth century from relying on astrology or holding superstitious beliefs. Federico’s attribution of the heavenly realm to the King of Naples was both a philosophical and a political statement.

Nonetheless, mythologizing was only one aspect of Renaissance politics. Federico had gained a lot of power over many years of relentless soldiering. He was the only hired captain of his generation who was truly successful. With Francesco Sforza, another condottiere who had managed to become head of a major state, he shared an early understanding of the centrality of propaganda in wars. Reporting a victory was always more important than winning an actual battle or than killing a large number of enemy soldiers and suffering fewer casualties. Discrediting the honor or reputation of the competitor, the general of the opposing army, was at least as important as actual deeds of heroism on the battlefield. Machiavelli later defined the virtue of the condottiere as a deadly combination of force and fraud. He thus evoked Federico’s ancestor Guido da Montefeltro; left to burn in Dante’s Inferno, Guido says:

le mie opere

non furon leonine, ma di volpe

the deeds I did

Were not those of a lion, but of a fox

A land of many foxes and few lions, Italy was the theater of silent war and constant betrayal. Hence the importance of friendship, sincere or simulated. Federico remembered that during a visit to Milan, Duke Galeazzo Sforza—who did not get on particularly well with his father’s friends—was so angry with him that he secretly had threatened to chop off his head. Fortunately for Federico, Cicco Simonetta had warned him in advance to flee.

The affection between Cicco and Federico evoked in the July 1477 letter had begun much earlier: the two had met during the hard-fought campaigns of the 1440s in the Montefeltro region. Cicco was then a young man from Calabria, serving the future Duke Francesco Sforza, himself only a freelance condottiere at that point. In 1444 Federico, at the age of twenty-two, became Count of Urbino overnight, immediately succeeding his stepbrother Oddantonio after the latter had been killed by disgruntled citizens. Rather conveniently, Federico had been waiting outside the city walls with his soldiers and later claimed he had had no knowledge of the plot, but he gladly accepted the title of count to rule the Urbinati.

Back then, Federico was the only loyal ally of Francesco Sforza. To celebrate the new dukedom acquired by Francesco in 1450, Federico arranged a joust that would demonstrate his “devotion” to the Sforza. But an accident happened: as a result of a mischievous move by his opponent, Federico lost his right eye. And so the lord of Urbino subsequently preferred to be portrayed in profile. Later, malicious rumors began to circulate according to which the duke also had his nose surgically carved after the accident to allow him to see an approaching killer from his blind side. At any rate, Federico took to wearing an eye patch.

Before his faithful scribe on that hot July day in 1477, however, Federico probably did not bother to cover up the long-scarred wound. The little hole of blackened skin would not have distracted the secretary when the duke, summoning his rigorous powers of concentration in the rising heat of the studiolo, resumed dictation of the letter to his old friend Cicco:

While all the reasons for which the dukes of Milan cannot make their foundations on the Signoria [government] of Venice are worth considering most prudently, and we might accept them as most true and without any contradiction, I cannot bring myself to like in the least the fact that the state of Milan is relying only on itself or on the alliance with Lorenzo, who is himself not secure, and is in fact extremely dangerous, as Messer Cicco knows better than me. He and his son Gian Giacomo cannot find any foundation in Lorenzo’s friendship and benevolence, since it can be seen in the past and in the present that Lorenzo does not care at all for the peace and progress of the Milanese state.

Dialectic is the art of refining the strength of an argument in a heated debate. Words can cut more than swords, even if they come from a professional soldier. Federico was attacking Lorenzo’s lack of steadfastness subtly and incisively. But why was he so angry with the young Medici?

FEDERICO’S FRIENDSHIP with Lorenzo seems to have peaked in 1472 when the Florentines hired the mercenary to wage a punitive campaign against Volterra. This Tuscan hill town was rich in alum mines, a major source of income for a Florentine consortium backed by the Medici bank. When the Volterrans refused to share the alum profits with Florence, Lorenzo had called Federico to wipe out the rebellion. Volterra is set in a nearly impregnable position, and the insurgents were holding out. After besieging and bombarding them for weeks, Federico finally obtained their unconditional surrender before unleashing his troops, who sacked the city, raped most of the women, and killed many of the men. One of the victims was a Jewish merchant named Menahem ben Aharon: his large collection of Hebrew manuscripts was seized by Federico, who proudly created a whole new section in his library.

A Hebrew manuscript pillaged by Federico during his merciless sack of Volterra and added to his growing library.

A Hebrew manuscript pillaged by Federico during his merciless sack of Volterra and added to his growing library.

Lorenzo ordered lavish celebrations in Florence to honor Federico’s deed. The condottiere was welcomed triumphantly to the city in the manner of an ancient Roman hero; he received banners embroidered with his coat of arms, along with splendid textiles wrought with gold. He was granted Florentine citizenship and was promised a glorious silver-gilt helmet embellished with enamel and a figure of Hercules subduing a griffin, the symbol of Volterra.

Federico da Montefeltro holding a copy of Cristoforo Landino’s Disputationes Camaldulenses, from the Montefeltro Library.

Federico da Montefeltro holding a copy of Cristoforo Landino’s Disputationes Camaldulenses, from the Montefeltro Library.

A few months later, along with the helmet, Federico received a highly precious, beautifully illuminated codex. The Florentine humanist Cristoforo Landino had dedicated to the prince of Urbino his Disputationes Camaldulenses. In the preface of this work, Federico was celebrated as the supreme champion of both the contemplative and the active life, the master of war who aimed for peace, the philosopher and commander who remained in spiritual touch with divine ideas and yet had a solid grip on reality.

Upon receiving the magnificent manuscript, Federico wrote a letter politely thanking both Landino and, in somewhat patronizing and condescending terms, Lorenzo, that most skilled “young man” whom he embraced “as a son with particular benevolence, and as a brother with honor.” Lorenzo himself appeared as one of the speakers in Landino’s dialogue championing action over contemplation and chose none other than Federico as a model. These are the laudatory words on statesmanship uttered by the fictional Florentine friend Lorenzo:

In our times we have Federico da Montefeltro, prince of Urbino, whom I doubtlessly consider worth comparing to the best captains of the ancient era. Many and most admirable are the virtues of such an excellent man: his penetrating wit is passionate about everything. He gives himself the leisure and the company of the most erudite and cultivated men, while reading many books, listening to many disputes, participating in many debates, as well as being a man of letters in his own right. However, if he had allowed his speculations to replace the vigilant hold on his state and the strong hand on his soldiers, he would have been reduced to nothing.

Such a balancing act between contemplation and action was undoubtedly easier described than performed. Lorenzo—Landino implied—had yet to learn how to juggle between the two from his proclaimed master. Landino was resorting to a highly contrived rhetoric, rather than using dialectic, the subtle art of investigating and conveying the truth. This was quite typical of Florentine culture: instead of sticking to hard factual logic, Florentines tended to create a soft fictional grammar. In his proudly presented Disputationes, Landino avoided any reference to the sack of Volterra, for instance. More poignantly, he wrote a commentary on Canto XXVII of Dante’s Inferno in which, when referring to Federico’s ancestor Guido, he described a politician’s ingegno, or wit, as the ability to be cunning and to discover covert ways to deceive without being caught. Covertness was precisely what one of the Montefeltro emblems represented: Federico had adopted from the House of Aragon the depiction of an ermine, with the motto NON MAI (never).

A Montefeltro family emblem with an ermine.

A Montefeltro family emblem with an ermine.

A Montefeltro family emblem with an ostrich.

A Montefeltro family emblem with an ostrich.

The ermine hides in dry, dark spots, and in order to find it, hunters surround its hideout with mud, since the furry animal does not ever want to dirty its gorgeous white fur. But prudence must be matched by toughness. Another emblem that had been in the Montefeltro family for a century showed an ostrich with an arrowhead in its beak; below, ran the ancient German motto HIC AN VORDAIT EN GROSSEN ISEN (I can swallow a big iron).

FEDERICO REMAINED FAITHFUL to these family mottoes as he wrote his letter to Cicco on July 2, 1477. Each smooth turn of phrase was an iron fist cloaked within a velvet glove. If Lorenzo really cared about Milan, Montefeltro argued in his highly factual, deceivingly precise prose, “he would not, from the beginning of Cicco’s regency, have opposed twice with such passion my coming to Milan, since I [Duke of Urbino] would not have desired anything but the good and honor of the duchy.” More to the point, Lorenzo “would not have kept up his contacts with the exiled Sforza brothers and Signor Roberto da Sanseverino, after having received information about their machinations” against Cicco, Duchess Bona, and the all-too-young Duke Gian Galeazzo.

Indeed Cicco had asked Federico to come to Milan twice before—first right after Galeazzo’s assassination and again after Cicco had expelled the Sforza brothers and Roberto da Sanseverino for plotting against him and the dukes. Roberto was clearly a hothead, although at least he had inherited his uncle’s Machiavellian virtue, or skill, as a condottiere. Thus, Federico wrote on: “in Florence they are trying to excuse Roberto while charging Cicco, showing with covert words that everything [the supposed Sforza plot revealed by Donato del Conte in May 1477] had sprung from Cicco and not from Roberto; they are also trying to contract the captain.”

Lorenzo’s leniency toward the rebel soldier Roberto was bad enough, implied Federico, but to actually maintain a friendship with the treacherous heirs of the murdered Galeazzo, as Lorenzo was doing, especially with Ludovico Sforza in Pisa, was even more damnable. The young Sforza brothers were weak and cowardly, and therefore very dangerous—as Cicco well knew. And so the old chancellor, fully in charge of the government, had to protect the young Duke Gian Galeazzo, the weak widow Duchess Bona, and himself from attack. Acutely aware of this, Federico continued to dictate:

Gian Giacomo says he wonders whether Lorenzo is sinning against the Holy Spirit. Well, I say he is, since he’s desperate for the grace of God, having offended the King of Naples and me—just a poor private gentleman…

The Montefeltro fox was packing several layered elements into this passage. Federico was the godfather of Cicco’s firstborn son, Gian Giacomo, and he had always been very protective of him. Hinting at Gian Giacomo’s doubts with regard to Lorenzo’s lacking “the grace of God” was a way for Federico to say something rather hostile while hiding behind his godchild’s qualms. And with “sinning against the Holy Spirit” he was referring, metaphorically and not so subtly, to the tense relationship between the Medici and the pope, Sixtus IV. Furthermore, Federico’s casting of himself as “a poor private gentleman” was also a message that Cicco could understand: Federico had been on bad terms with the “lowly merchant and citizen” Lorenzo for some time, and Cicco knew about it. The warnings that followed in the letter could hardly come as a surprise:

I cannot concur with the opinion of the Magnificent Messer Cicco according to which it is good to be so careful not to displease Lorenzo just to go after Lorenzo’s dangerous dangers and passions…He could not hate Cicco more, as he has always hated him, at all times. And I do have true notice of it. And if it were otherwise, I would not speak like this. Although Lorenzo is, for no reason, so ill-disposed towards me, I would never put my special interest before the truthful and dutiful reason in such important matters, since I know all too well that in case I need any help, I can be helped by your State only if it stays strong, and that I would not be able to help the State, if it is not quiet and secure. This is so clear, that in my view it makes itself understood.

This passage is replete with innuendos and reads almost like a tract on political behavior—Machiavelli avant la lettre. Federico touches here on a very delicate subject: the Simonettas, like the Sforzas, were upstarts in Milan and had gained all their power on the basis of their merits and abilities despite, rather than because of, their blood. By pointing out the Medici family’s hatred, a word that meant something more like disdain, for the lowly Simonetta chancellor, the Duke of Urbino was forcing Cicco to reconsider his friendship and excessive kindness to Lorenzo merely as a hopeless attempt to become part of a class to which he did not belong.

Federico warned Cicco that “he better not want to follow Lorenzo into the abyss: he should rather be pulling him in his direction.” The consequences of such a perilous choice were unspoken, but nonetheless clear. The Duke of Urbino outlined the “dangerous dangers” threatening the Duchy of Milan, and he emphasized them to scare Cicco. He then smoothly moved on to the strategic perspective of Naples. This was the most sensitive point in Federico’s scheme against Lorenzo: he had to persuade Cicco to trust the King of Naples as much as Federico himself had trust in the seasoned chancellor. He introduced the topic in the most flattering language:

I want you to be sure that the King has always thought that in the Milanese state there could never have been a person more suited to the requirements of the task than his Magnificence, as the one who, with his long experience, prudence, and exceptional faith, has surpassed anybody else, and if there had not been one like him, we would have had to create one of wax!

Francesco Sforza had once famously responded to an envious Milanese courtier who had suggested that Cicco’s immense power be reduced, that Francesco as a duke could not do without his trusted chancellor, and that he would have to make a “clone” out of wax if he ever lost the original. Federico was familiar with this saying about Cicco, a proverb of sorts in Milan by then. By quoting it, Federico was at his most ingratiating, and therefore it was safe for him to move on to the next most delicate topic.

Federico informed Cicco that he was sending his trusted chancellor Piero Felici to the King of Naples “with such instructions that everything will be all right, avoiding any fabricated charge against Cicco or Gian Giacomo”—as if any charge should be made against them in the first place. In other words, if Cicco did not side with the king, he would find himself under attack. The affectionate assurances at the end of the long letter hardly made the overall message less threatening:

Cicco’s and our common sons’ interests are in my heart, especially that of my Gian Giacomo, no less than those of my own state and life.

—Given in Gubbio, Second Day of July 1477, Federicus dux etc.

Federico must have paused for a minute, while his secretary wiped small beads of sweat from his forehead. One can imagine that the secretary’s hand was hurting from scribbling away. The duke might have looked at him with a hint of irony while the scribe was preparing to leave. Then Federico’s face would have turned stony and serious again. He decided to add a short, unambiguous postscript:

P.S. The “general league” [of Milan, Florence and Venice] cannot succeed unless Lorenzo is made aware that he won’t be allowed to govern the state of Florence, and that nobody will be above the King of Naples (the King will be under nobody’s will).

Finally the secretary wrapped up the letter and was ready to go to his office to transcribe it into cipher. Federico instructed him to use as many varied and void characters as possible, so that the letter would be practically impossible to decipher if it should fall into enemy hands. The code would be more complex than the usual one between Federico and Cicco.

Cicco would certainly have appreciated the cipher. Indeed, if Montefeltro was credited with the composition of a little treatise on code-writing, De furtivis litteris, Cicco was the master in code-breaking and the inventor of the most complex ciphers to date. For the enemy to break an intercepted dispatch from Milan might take months, if not years. By the time the solution to the code was found, the information would be obsolete.

But the most important part of communication was still left to the old art of dialectic, to its subtle powers of persuasion. Federico had used his most convoluted prose to convey a very simple message: that Cicco better cut the old ties between Milan and Florence and side with Naples, if he wanted to survive. But the Duke of Urbino had been extremely careful not to mention the pope in his cunning letter. He counted on the fact that Cicco was well aware of Lorenzo’s extremely tense relationship with Rome. There was no need to speak about it openly, or even in code.