6

FLORENCE IS FOR FEAR

FLORENCE HAS NOT CHANGED DRAMATICALLY SINCE THE DAY OF THE PAZZI CONSPIRACY. IN FACT, MOST OF ITS CHIEF MONUMENTS WERE ALREADY IN PLACE. Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome on the cathedral dedicated to Santa Maria del Fiore had been completed in the 1430s, and the Palazzo Medici in the 1440s. Palazzo Vecchio, as its name suggests, was even older. In the 1560s it was linked with a tall bridge to the Uffizi Palace (today a museum), and with Vasari’s corridor to the Palazzo Pitti on the other side of the river Arno, across the Ponte Vecchio. The corridor was intended as a safe passageway, an escape route for the members of the ruling Medici in case of an attempted coup. By then, history had taught a valuable lesson to the family, whose dynastic power would not be extinguished until the eighteenth century, when its last member, Anna Maria Ludovica, died peacefully, willing all her possessions to the Tuscan grand duchy.

Florence is now one of the top tourist destinations in the world. Most people visit the Duomo or the Medici tombs at the back of the Basilica of San Lorenzo, once the Medici family’s church. In both places they may hear the famous and shocking story of the assault on Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici. But they are rarely told all of the horrific details of that gruesome day.

There are a few published Renaissance reports and literary adaptations of these events, but one in particular was overlooked for many years. It is a manuscript, today housed at the Vatican Library, written by Giovanni di Carlo, a Dominican friar who was at the time the prior of Santa Maria Novella, the second most important church in Florence. Between 1480 and 1482 he composed a History of His Times in three books, each based on the struggles of a leading member of the Medici family to rise to power or to maintain it: Cosimo returning from exile (1434), Piero resisting the early Pitti conspiracy (1466), and Lorenzo surviving the Pazzi conspiracy (1478). I have drawn many firsthand details from Giovanni di Carlo’s account. Niccolò Machiavelli ransacked much of it in his Florentine Histories (1525), commissioned by the Medici pope, Clement VII, son of the murdered Giuliano. Giovanni had witnessed the events in person but since he was not a Medici client he had a slightly less biased take on them than would Machiavelli.

BLOODY SUNDAY

FLORENCE, APRIL 26, 1478

ON THE DAY THEY WERE GOING TO KILL HIM, G IULIANO de’ Medici woke up with a stomachache. This unpleasant indisposition had, in fact, saved his life only a few days earlier, when it had prevented him from attending a banquet in Fiesole to which the plotters had invited him along with his brother Lorenzo. Francesco Pazzi had left behind his Roman bank business to join Cardinal Riario, Archbishop Salviati, and the others in the Pazzi’s Villa La Loggia, two miles outside Florence. They had asked Lorenzo to organize a banquet at his own beautiful villa on the hills of Fiesole (he enjoyed large dinner parties) and then to visit the Badia, a monastery built by Cosimo. They knew of a secret room there, accessible through a spiral staircase, where it would have been easy to trap and quietly murder the Medici brothers. The Pazzi had also asked both of them to come to Fiesole with only a small entourage, since they wanted all of them to starsi alla dimesticha, to feel at home, and to be attended only by their servants. But that day Giuliano had an anghio, a biting stomachache, and could not come. When Lorenzo showed up on his own, the plotters tried to convince him to call for his brother, but to no avail. Since they wanted to kill them both, they refrained from taking action on that occasion.

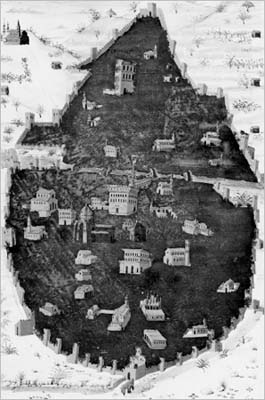

Map of Florence in Poggio Bracciolini’s Florentine History. Poggio’s son Jacopo dedicated this copy to Federico himself. Jacopo, one of the plotters against Lorenzo, ended up hanged from the upper windows of the Palazzo Vecchio, at the center of the map.

Map of Florence in Poggio Bracciolini’s Florentine History. Poggio’s son Jacopo dedicated this copy to Federico himself. Jacopo, one of the plotters against Lorenzo, ended up hanged from the upper windows of the Palazzo Vecchio, at the center of the map.

Over the next few days, Giuliano ignored many warning signs and bad omens. He had horrible dreams, though these might very well have arisen from his stomach problem. He was very slender and ate little. He was only twenty-five years old, with an open face, and a modest and benign countenance. He was easygoing, handsome, and gracious, and thus endeared himself to everyone. He was very different, in other words, from Lorenzo, who was obsessed with his own success and oblivious to the possibility of a turn in his fortunes, and who never hesitated to favor his acolytes, even non-Florentines, over the interests of the local citizens. Giuliano, revolted by Lorenzo’s ambition (Giovanni di Carlo used the Latin word stomacans: literally, nauseated to the stomach), had once said to his brother: “Watch out, O brother: by wanting too many things, all of us might lose everything.” Perhaps his stomachache was a political premonition.

On the day Giuliano was going to be killed, the Medici brothers were planning to throw another lavish banquet in their palace in Florence for Cardinal Riario, who had never been there and claimed he wanted to see the Medici’s famous collection of artworks, medals, and coins for himself. The plotters had arranged for the cardinal to celebrate High Mass that Ascension Sunday in Florence’s Santa Maria del Fiore, the Duomo. The banquet was planned as the after-Mass reception, which would have to be worthy of a princely household.

Scores of waiters were ready to serve an elaborate meal at the elegantly laid tables, lavishly decorated with a profusion of tableware and linen. Tapestries adorned the walls and carpets covered the floors throughout the house. Festive garlands hung everywhere. Ephemeral contraptions of all sorts, exotic Eastern cloths, and stuffed animals, both wild and domesticated, were on show, gifts once supplied to the hosts’ ancestor Cosimo the Elder, in whose age “a cargo of Indian spices and Greek books were often imported in the same vessel.” In another section of the palace, gold and silver vases, ancient and new, were displayed alongside precious statues, stones, gems, and jewels, some of them intended as gifts for the cardinal. Amid this show of material wealth and magnificence, the brothers went about their tasks in a state of fevered anticipation. Giovanni di Carlo later quoted a line of Virgil’s from the Aeneid: “This was the last day in which we, miserable creatures, were to decorate our city with festoons, while our destruction was imminent.” Cardinal Riario’s expedition was a Trojan horse. The new plan was to kill the brothers inside their own palace and sack all their property.

ON SUNDAY MORNING, after arranging the military details outside the city, the plotters left the Villa La Loggia and rode on horseback to Florence. The company included Cardinal Riario, Archbishop Salviati, Gian Battista Montesecco, and Jacopo Bracciolini, who was acting as a secretary to the cardinal. Meanwhile, a group of Florentine citizens converged on foot in the direction of the Duomo. It was led by Pazzi family members, among them the unwitting Guglielmo, Francesco’s brother and Lorenzo’s brother-in-law. The members of this substantial brigata concealed weapons under their elegant clothing.

The riders dismounted at the Palazzo Medici, where no one welcomed them since they were expected to go directly to Santa Maria del Fiore. Only after Mass were they supposed to walk to the banquet. This misunderstanding created a bit of mayhem. When the Medici brothers heard about the cardinal’s arrival, they left the Duomo to fetch him at their palace. Cardinal Riario had changed from his riding dress into his ecclesiastical garb. They all met in the courtyard, under the thin shadow of Donatello’s bronze David. Lorenzo politely kissed the ring on the young cardinal’s hand, as did Giuliano. They walked back on via de’ Martelli toward the church. Giuliano was walking between Francesco Pazzi and Bernardo Bandini (another student of the philosopher Marsilio Ficino), who embraced him fulsomely in order to check whether or not he was wearing a breastplate under his red robe. As Machiavelli would later remark, hiding so much hatred behind dissembling hearts was a “thing truly worthy of memory.”

Cardinal Riario, barely seventeen, admired the baptistry with its golden door, and the unfinished marble façade, for which Lorenzo himself had submitted a design. Once inside the cathedral, he marveled at its outstanding dome. Lorenzo and Giuliano let the cardinal take his seat under the cupola, where he would celebrate the Mass. They then circled the choir on opposite sides, at a good distance from one another—a precaution the brothers customarily took in public.

The cathedral was filled with the chatter of well-dressed citizens. In the hubbub, Giovanni Tornabuoni, the brothers’ loving uncle, said aloud that Giuliano was not well and that he might not attend the banquet later. Somebody else spread the rumor that a number of unidentified crossbowmen had been spotted outside the city gates (they were in fact Federico’s men). Francesco Pazzi and Bernardo Bandini overheard this too. They had to hurry. That morning they had revealed their intentions to too many accomplices and the longer they delayed, the greater the danger of their being caught before the act. They eagerly waited for the moment to strike and, abandoning their plans to kill him later at the palace, started moving toward Giuliano.

Giuliano was blissfully listening to the “Agnus Dei”—Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi (Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world)—while, next to Cardinal Riario, a Florentine priest raised the Holy Bread of Christ. Francesco and Bernardo, in their hooded cloaks, silently approached their target along with some servants. Using a short dagger, Bernardo struck Giuliano in the side, murmuring, “Take this, traitor!” Then Francesco plunged another blade into Giuliano’s chest. Giuliano shrank back a few steps, holding his abdomen, then fell to the ground. The murderers kept raging over him, cracking his skull with a heavy weapon. The assault was so violent that Francesco wounded himself in the thigh.

On the other side of the altar, killers appointed at the last minute—two disgruntled priests—proceeded haphazardly with their given task. Unlike Montesecco, who backed out at the last minute in a sudden crisis of conscience, Jacopo Pazzi’s chaplain and chancellor (one Stefano da Bagnone) and the apostolic secretary Antonio Maffei of Volterra evidently had no scruples about perpetrating a killing in a church. But they approached Lorenzo too slowly and were unable to hit him effectively. He instinctively turned, avoiding the full force of the first knife blow and suffering only a light wound on his neck. Lorenzo’s friend Franceschino Nori, who threw himself in the way of the attackers, was wounded in the stomach and struck down.

Lorenzo was quick to wrap his mantle around his left arm and to draw a dagger in his right hand. He deflected another couple of swipes, and while his brother’s killers were coming after him, he ran into the Old Sacristy, to the left of the main altar, helped by a young man from a wealthy family Lorenzo happened to have graced and liberated from jail just days before. Lorenzo and a few loyal friends shut the heavy bronze doors behind them and looked at each other anxiously. One Antonio Ridolfi, a longtime Medici client, thought that the offending blades might have been poisoned. Bravely, he sucked Lorenzo’s wound.

Panic and confusion took hold in the cathedral. The crowd of fashionable citizens started running out, according to one witness, with their hearts in their throats. Some women screamed hysterically. General pandemonium broke out.

Just before the attack on the two brothers, Archbishop Salviati, who was sitting next to the cardinal, had left suddenly, claiming that he had to visit his ailing mother whom he had not seen in a very long time (hardly an impressive excuse for such a bold schemer). He was actually headed for the Signoria in the Palazzo Vecchio with his servants and Jacopo Bracciolini, intending to take over the government seat, the ultimate symbol of Florentine freedom. It was almost noon (the Mass had been delayed by the cardinal’s late arrival) and the city officials were ready for lunch. In Italy it is rarely a good idea to interrupt someone’s lunch. When Archbishop Salviati appeared unannounced, they became suspicious. The most inquisitive among them, Cesare Petrucci, a veteran militiaman, quickly saw through Salviati’s garbled claims. He drew his sword and with the help of the servants kicked the archbishop and his men out of the room. In the meantime, Jacopo Bracciolini and some others had sneaked into the chancellery of the Signoria. The security door locked behind them, though, and it could not be opened without a secret key. They had set themselves up.

The Sonare di Palagio, a set of bells that was used as the government’s emergency call to arms, was rung. Jacopo Pazzi reached the piazza on horseback at the head of a small army of hired soldiers and desperately tried to act as a ringleader, shouting “Hail to the People!” and “Freedom!” But the people took up their weapons and cried “Palle, palle!” (Balls, balls!, a reference to the Medici coat of arms) and “Arme, arme!” (To arms! To arms!). The staircases of the Signoria soon became a battleground. By the end of the fight, the steps were covered in blood and amputated human limbs. Scattered around were severed hands still holding swords and other blades.

ACCORDING TO GIOVANNI DI CARLO’S History, the sudden change of plan in the Pazzi plot was reminiscent of Gian Andrea Lampugnani’s attack on the Duke of Milan in Santo Stefano sixteen months earlier. But the anti-Medici plotters either applied excessive force or lacked energy and precision. In any event, they did not achieve the same level of success as the Milanese killers, who had been practicing on a wooden dummy for weeks before the actual attack.

The military action throughout the conspiracy had been ineffectively executed. Preventing the Sonare di Palagio from ringing was key to allowing external troops into Florence. Once the bells had rung, all the city gates were sealed. Federico da Montefeltro must have been very disappointed with the feebleness of the conspirators. The only experienced soldier among them was Montesecco, who had refused to take the initiative on moral or religious grounds. The rest of the bunch were dilettantes of violence—mere big mouths, as Sixtus himself had reportedly described them to Montesecco.

The Pazzi conspiracy: in the mayhem Giuliano de’ Medici lies dead on the floor of the Duomo in Florence. A twentieth-century etching.

The Pazzi conspiracy: in the mayhem Giuliano de’ Medici lies dead on the floor of the Duomo in Florence. A twentieth-century etching.

Gian Battista Montesecco claimed that he had wanted to tell Lorenzo everything about the plot, but that he had not managed to do so. Giovanni di Carlo says that Gian Battista was a “naive soul” and found the murder of a gifted young man repugnant on principle. Gian Battista had not dared to kill in a holy church. He had refused to commit sacrilege, betrayal, and homicide.

About an hour after the attack in the church, Lorenzo managed to come out of the Old Sacristy. Armed followers and trustworthy friends came knocking on the bronze doors and explained that the uprising was being put down by the enraged Florentines. The very people the Pazzi had counted on to topple the Medici regime had turned against the conspirators and crushed them. Lorenzo walked out of the cathedral and was hurriedly escorted back to his palace, where the elaborate banquet lay untouched. He was probably not given the chance to see his brother’s corpse lying on the floor in a pool of his own blood. Giuliano had been stabbed nineteen times. Franceschino Nori had died of his stomach wound.

PAYBACK TIME

AS SOON AS THE NEWS OF LORENZO’S SURVIVAL SPREAD IN THE streets, people rejoiced. His nearly miraculous escape reinforced their leader’s power. His vendetta was carried out swiftly and without pity. The immediate, chaotic aftermath of the conspiracy was vividly described to Cicco Simonetta by Filippo Sacramoro, the Sforza ambassador in Florence, in a letter dated April 27. In the hours after his brother’s assassination, Lorenzo, already recovering from the wound to his neck, walked around the Medici palace dressed in mourning clothes. He occasionally waved from the window to the crowds gathered in the streets or in the courtyard to express their sympathy and allegiance. The popular rage had not been prompted by Lorenzo, insisted Sacramoro.

The Florentine militia seized Francesco Pazzi, stark naked, from his private room in the family palazzo, where he was contemplating suicide. But he preferred to face certain death for the “ferocity of his soul,” as Giovanni di Carlo put it. Francesco was dragged into the streets, still bleeding from his thigh, tried on the spot, and hanged from the upper windows of the Palazzo Vecchio. Archbishop Salviati was given the chance to make his own confession: “Sacer, unctus, archiepiscopus sum” (I am holy, anointed, archbishop), he intoned, before he was hanged in his church robes, along with some close family members. Salviati had blamed Jacopo Pazzi for pushing him to the deed during the course of the past three years and claimed that he did not need any of this bloodshed, since he had an honorable archbishopric worth four thousand ducats a year and was waiting “in the name of the Holy Spirit to be pronounced cardinal.” An epigram was circulated after the hanging, about Salviati wearing his sacred miter: in the tradition of Florentine gallows humor, the archbishop’s skirt was said to be dangling like a bell. According to a gory urban legend, while the archbishop was hanging next to Francesco Pazzi, he bit him so violently in the chest in the midst of a furious death spasm that his teeth remained stuck in the flesh of his former friend.

Cardinal Riario, in the midst of this mayhem, had found refuge among the canons of the cathedral. By evening, however, two government officials had escorted the cardinal from the Duomo to the prison in the Palazzo Vecchio. Jailed as an invaluable hostage, he was forced to describe to the Holy Father, writing in his own hand, all that had happened. Jacopo Pazzi had fled through the Gate of the Cross, whose guards he had bribed beforehand. He was caught in the countryside and brought back on a stretcher, surrounded by shouting people, and hanged in Piazza della Signoria with all of his servants.

For a few days Montesecco’s fate remained a mystery. He was the commander of fifty infantrymen and crossbowmen on horseback, some of whom had been killed during the riots, while others had fled with Jacopo Pazzi. No one knew whether Montesecco himself had been killed in the failed attack against the Palazzo Vecchio. Somebody did claim from li indicij de li panni—clues indicated by the clothing—that one of the corpses was his. But Giovanni di Carlo chillingly reports that the bodies had been disfigured to such an extent that many became unrecognizable.

In fact, Montesecco would not be caught until three days later. He was the only one of the plotters to be beheaded at the Porta del Podestà, the usual place for executions. All the others were hanged or torn to pieces by the populace. Jacopo Bracciolini, the treacherous humanist, had been caught, grabbed by the hair, and left hanging by his neck from the windows of the Palazzo Vecchio. The ropes were then cut and his corpse fell to the ground. Many of the other hired accessories were simply pushed alive from the upper floors of the building. Their remains were dragged around the piazza. About eighty people died altogether, including Stefano da Bagnone, the chaplain, and Antonio Maffei of Volterra, the apostolic secretary, the two priests who had tried to kill Lorenzo.

In the ensuing days, all the financial assets of the Pazzi banking dynasty, in Florence and elsewhere, were frozen. The few surviving male members of the family (among them Guglielmo, Lorenzo’s brother-in-law, who was saved by his wife’s pleading) were thrown into the dungeons of Volterra to serve life sentences. The tombstones of the Pazzi ancestors were erased, and the family portraits wiped out. As for the Pazzi women, they were forbidden to marry. Jacopo’s daughter was deprived of all the jewels, clothes, rings, gems, and other ornaments that her doting father had given her. Her cloistered suffering after the attack was undoubtedly worsened by the fact that she had previously led such a pampered existence.

In the weeks following his hanging, Jacopo Pazzi’s rotting corpse was disinterred twice. First the populace took it from the Pazzi Chapel in Santa Croce, and reburied it in unconsecrated ground outside the walls of Florence. Then they dug it up a second time and dragged it around the streets on the rope from which he had been hanged and threw it into the Arno. Reportedly, the bridges were crowded with people watching him float in the waters swollen by heavy spring rains. Then it was once again fished out and hung on a willow tree before being cut down, thrown back into the Arno, and left to drift all the way to Pisa and out to the sea beyond.

A BROTHERLY BURIAL

ON THE LAST DAY OF APRIL, THE FUNERAL OF GIULIANO DE’ Medici was celebrated. The Duomo, site of the horrific stabbing, was hardly an appropriate location for the ceremony, so it took place in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, where the remains of the Medici ancestors rested peacefully behind the church’s unfinished façade. In addition, the basilica was conveniently close to the Palazzo Medici.

This three-story palazzo looks like an elegant fortress, and its protective function now seemed more essential than ever. To get to the church for his brother’s funeral, Lorenzo simply had to sneak out the rear entrance of the building, walk past the beautiful private garden crowded with bronze and marble statues, and cross the busy San Lorenzo piazza. Here he had only to climb Brunelleschi’s stairway to reach the church. For such a short trip, less than a minute in length, Lorenzo was accompanied by twelve armed bodyguards. Fear was still hovering over Florence, and its surviving leader had to watch every step.

The service for Giuliano was remarkably modest. While many citizens wanted him to be buried with greater pageantry, Lorenzo wished his brother’s funeral to be austere, like those of his father and grandfather. Through this understated approach to mourning, Lorenzo was reaffirming the continuity of the Medici dynasty. Giuliano’s funeral was held at the same time as that of Lorenzo’s friend Franceschino Nori, who had sacrificed his life to protect Lorenzo from the attack. This double ceremony signaled the rekindling of a mutual affection between Lorenzo and his people.

Terra-cotta bust of Giuliano de’ Medici, ca. 1475.

Terra-cotta bust of Giuliano de’ Medici, ca. 1475.

Cold-blooded politics, emotional tragedy, and refined taste coexisted to a shocking degree in the Italian Renaissance. Not long after his brother’s death, for instance, Lorenzo commissioned the great sculptor Andrea Verrocchio to create three life-size terra-cotta busts depicting Giuliano, for display in the main Florentine churches. In one of them, Giuliano looks cheerful and cocky, dressed in an elegant breastplate of the sort that, had he been wearing it on the morning of April 26, would have protected him from his killers’ knives.

A painted portrait that Lorenzo also commissioned shows Giuliano’s image postmortem. His red robe blankets him like a shroud of death ready to be pulled over his dignified face. His eyes are almost shut, and his head is turned, giving him an appearance of sternness. The window behind him is ajar, as if the light of an Italian afternoon would be too strong for him to bear. This intimate, allegorical touch was painted by none other than the great Sandro Botticelli, a close friend of both brothers. At Lorenzo’s request, this picture was not intended for public display, but was probably hung next to the portrait of Galeazzo Sforza in Lorenzo’s bedroom, a work that seems to be its visual counterpart: by freezing the body, lowering the gaze, and casting the face in shadow, the active and celebratory image of the first portrait was transformed into one of contemplative mourning.

Ultimately, however, Lorenzo was a master of propaganda. A commemorative bronze medal that he had cast by Bertoldo di Giovanni was meant to reach the largest audience. The two sides of the medal show mirror images of the cowardly attack as seen from either corner of the Duomo altar. The plotters are dwarfed by the imposing profiles of the Medici brothers. The two Medicis resemble Botticelli’s angels, in a slightly more masculine guise. Under the faces of Giuliano and Lorenzo are set the inscriptions “Public Mourning” and “Public Safety,” respectively.

Portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici by Sandro Botticelli, ca. 1478.

Portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici by Sandro Botticelli, ca. 1478.

The Pazzi Medal, struck by Bertoldo di Giovanni in 1478.

The Pazzi Medal, struck by Bertoldo di Giovanni in 1478.

Lorenzo was an astute politician. But even as a political leader, he never gave up his literary ambitions. He was a prolific writer, composing light verse and serious poetry; he also compiled a collection of sonnets with his own commentary. Oddly, though, he did not leave us a single line commemorating his brother. It could be that writers were already officially at work on this task. Angelo Poliziano was in the middle of his poem Stanze cominciate per la giostra del Magnifico Giuliano de’ Medici (Stanzas Begun for the Joust of the Magnificent Giuliano de’ Medici) when the plotters left the subject floating in a pool of his own blood. The day of the attack, Poliziano approached the corpse lovingly and counted the stab wounds on it, as he touchingly reported in his commissioned account of the Pazzi plot. But the poet wanted to celebrate Giuliano’s love of life and did not dare touch the Stanze after his hero’s death. The poem describes the romance of young “Julio” and his mistress “Simonetta”—Simonetta Cattaneo—by means of a poetic transfiguration. There is, however, little psychological reliability in this idealized portrayal.

The stunning Simonetta, a married woman who died young in 1476, had received a state funeral that was actually more solemn and heartfelt than Giuliano’s. But she had not been his only mistress. Before his death, it seems, Lorenzo’s brother had left a sign of his mortal presence in the womb of a less lofty lady. Fioretta Gorini was seven months pregnant with Giuliano’s child on April 26, 1478, the day of his murder. In late June she gave birth to a baby boy who was, not surprisingly, christened Giulio. This fatherless, illegitimate child, adopted by his grieving uncle Lorenzo, would be raised as a member of the Medici clan, eventually becoming a cardinal and finally a pope, under the name of Clement VII.

Le temps revient (time returns) was the Medici motto. Lorenzo expressed his brotherly love through clever patronage and the adoption of the deceased’s illegitimate child. He also treasured the family memories of the brothers’ childhood. In 1459 Benozzo Gozzoli had painted a gorgeous fresco cycle in the Medici Chapel inside the palazzo. This work depicted a large retinue accompanying the Three Magi as they paid homage to the newborn Christ child. In the midst of the multicolored crowd of noble Florentines and foreign guests from Europe and the Near East, three characters were shown: Lorenzo himself, his tutor Gentile Becchi, and his brother Giuliano.

Giuliano is the figure in the background, sandwiched between his brother’s prominent nose and the teacher’s protective gaze. The painter’s subtle positioning of the figures provides insight into the Medici family dynamics. The firstborn, overwhelmingly bright and ambitious, would always cast his shadow on the younger, slightly less talented sibling. And now the shadow of death had engulfed him, at the age of twenty-five.

After Giuliano and Nori’s funeral, Lorenzo did not set foot in the street for two days, remaining sheltered in the family palazzo. In the middle of the courtyard he could see Donatello’s bronze sculpture of David, the graceful killer of the evil giant, an emblem of beauty, youth, and effortless physical skill. This slim nude figure stood on top of a column in the middle of the Medici courtyard, triumphant over Goliath’s severed head. The short, bloody sword hanging from those delicate teenage hands might have now seemed like a chilling reminder of the recent carnage. And although Lorenzo swiftly recovered from the slight wound on his neck that he had received in the Duomo, the worst was still to come.