7

EXTREME MEASURES

HISTORIAN NICOLAI RUBINSTEIN OPENS HIS FAMOUSLY WELL-DOCUMENTED AND NOW CANONICAL BOOK, THE GOVERNMENT OF FLORENCE UNDER THE MEDICI (1434-1494), BY WRITING: “The political régime which was founded by Cosimo de’ Medici and perfected by his grandson Lorenzo differed from the despotic states of fifteenth-century Italy in the preservation of republican institutions. Described as a tyranny by its enemies, its critics had to admit that the Medici acted within the framework of the constitution.”

The great challenge for Lorenzo, in the immediate aftermath of the Pazzi plot, was to preserve the appearance of a republican regime while defending his status as the wounded, unofficial leader of the Florentine state. Since December 1469, when at age twenty he had taken over the role of first citizen from his late father, Lorenzo had managed to walk a fine line as both the guarantor of the people’s liberty and the richest and most powerful member of the community. If Galeazzo Maria Sforza, the Duke of Milan, “thought, in January 1471, that Lorenzo, ‘having begun to understand what medicine he needed,’ might make a bid for despotic government, he was clearly mistaken,” Rubinstein reminds us, arguing that Lorenzo’s ascendancy in Florence was enhanced by the fact that he did not act like a petty tyrant. When he came under attack personally in 1478, a large part of the citizenry, which depended on the Medici goodwill, spontaneously rose to his defense not out of fear, as had been the case after Galeazzo’s murder in Milan, but out of rage and worry that their freedom might be jeopardized. Lorenzo’s survival in the wake of his brother’s death paved the way for a new, insidious form of republican regime that justified some anticonstitutional, extreme measures to face the terrorizing urgency of the unexpected political circumstances. This was to be the new Medici medicine.

THE CONDOTTIERE’S CONSCIENCE

ON MAY 2, 1478, FLORENTINES WERE STILL BEWILDERED AND overwhelmed by sadness. Calendimaggio (the May Day Feast, a celebration of the coming of spring), traditionally one of the most colorful and cheerful occasions in the Florentine calendar, had been canceled due to the civic mourning for Giuliano de’ Medici. That morning, just a week after his brother’s assassination, Lorenzo received a letter that had been rushed overnight from the steep hills of Urbino. It conveyed Federico da Montefeltro’s official condolences. The duke wrote that he had been informed, both by Lorenzo’s letter (which has been lost) and “through many other channels,” of the “horrendous and despicable attack” against Giuliano, for which he felt “deep displeasure and immense pain”:

Nonetheless, things having happened in the way they did, through the divine grace and virtue of Your Magnificence and the extraordinary love and faith demonstrated by this magnificent people and by your friends, you have to be very content and thank God! And since things, God be thanked, happened in the way that they did, I do not consider it is necessary right now that I offer my assistance otherwise than by thanking Your Magnificence who with so much trust and love has communicated to me this adverse occurrence. I want to make sure that in the future Your Magnificence realizes that I am available to help you. As soon as you request my help, I will give it gladly and willingly, as I have done at all other times and to satisfy you in part with that charity and love that you require. I would prefer that Your Magnificence and the others who have to govern Italy chose a path in which the passions might abate, otherwise they will so easily lead to a disturbance. It is hard to overstate how much good springs from straightening things up in the beginning, and much more than could be fathomed; but on the contrary, when from the beginning one slides little by little into an uncomfortable situation, it picks up momentum, so much so that one could hardly remedy it. And Your Magnificence, by benefiting from your own prudence and potency, I believe that you should try hard to make it right by God and by the world; moreover, you are doing so well—by the grace of God—that more than anybody else you should desire peace and general quiet.

Most historians have never questioned the good faith and sympathetic intentions expressed by this letter. The recipient, however, must have read it very differently. Once he had penetrated the writer’s intricate, contorted style, Lorenzo could hardly have believed his eyes. What was Federico talking about? God be thanked, make it right by God and by the world, by the grace of God! Lorenzo was still grieving for his brother, and now he was being asked to be patient and passive, and be grateful to the God who had not protected his beloved sibling in God’s own house?

The tone, the content, and especially the closing sentences of the letter conveyed little in the spirit of condolence. On the contrary, this was, in fact, a threatening, implicit declaration of war. The offer of help was rhetorically empty. The message, once rhetorically decoded, stripped of its formalities, was clear: Lorenzo should consider himself lucky not to be dead, and if he wanted to live, he had better be quiet and do nothing to disturb God—God in this case being none other than the worldly and wrathful vicar, Pope Sixtus IV, and his henchman, Federico.

By the time he received the letter, though, Lorenzo was already aware that Montefeltro must have had a hand in the conspiracy. The Milanese envoy in Florence shared with Cicco concerned reports about the “son of the Duke of Urbino,” the illegitimate Antonio, captain of the Sienese army, who had apparently been called from Siena to fight against Florence. And he had learned that eight soldiers, all but one in the Urbino uniform, had been captured on the outskirts of Florence and hanged on the spot.

Once he had read this friendly letter, Lorenzo’s earlier suspicion that Federico had supported and perhaps even engineered the attack must have turned to certainty. Now he faced the difficult task of deciding how to respond to this offensive missive, one that wounded his personal pride as much as it threatened his political power. In the whole of Italy, there was only one person Lorenzo could still trust: his single true ally, Cicco Simonetta, the regent of the Milanese state. Already on May 3, the Sforza ambassador in Florence replied to Cicco, who had proposed “suspending the bargaining around the condotta [hiring contract] of the Duke of Urbino,” that Lorenzo was “of the same opinion.” They agreed to abolish his stipend, the condottiere’s livelihood.

On May 4, in the hours before his execution, Gian Battista, Count of Montesecco, the papal soldier and former subject of the Duke of Urbino, handed over the confession about the organization of the plot that his jailers had seen him writing. The document was an indictment of the pope and his clan, including Montefeltro. Yet when the Florentine chancery published Montesecco’s confession later in the summer, they were careful to expunge the sections of the text relating to the Duke of Urbino. The doctored version of the incriminating document would serve the purpose of leaving the door open for Federico, so he might switch sides without losing face.

In Florence nobody dared say in public that the Duke of Urbino was directly implicated in the plot. However, some gossip was circulating widely, albeit prudently. An anonymous Florentine poem stated that involved in the plot were “others of great condition, / but it is better not to speak their names / although each of them was born of humble origins, / so that anyone can guess who they are.” The reference to the fact that Federico was a bastard son (and so was Ferrante of Aragon, King of Naples) was quite obvious for anybody in Italy at the time. Another poem, attributed to Luigi Pulci and addressed to Giuliano’s pious mother, Lucrezia Tornabuoni, attacked the Roman Church as underworld god Pluto’s “new wife,” as a poisonous Babylon, and as a “schismatic synagogue.” There was no need to spell out Sixtus IV’s name.

Once Montesecco’s confession became known, Federico was not sure whether he would be accused openly and started to feel pressure. On May 8, he decided to write Cicco a wordy letter, filled with partial confessions and warnings, trying to prevent the impending rupture between them. This letter is an extraordinary blend of political dissimulation and truth, demonstrating how deeply Montefeltro was involved in the plot:

From this situation in Florence, which you know about, I have felt and still feel a great displeasure for many reasons, as I have also conveyed to the Magnificent Lorenzo de’ Medici, who wrote to me. And certainly, however horrendous the case was, it can better be seen through the great violence of offenses received which pushes others to put themselves at such risk, like these wretches of the Pazzi household did. They did not consider or fear death or the ultimate destruction of their lineage. To be fair, Lorenzo de’ Medici in some instances has let himself go beyond reason, and not only against the Pazzi but also against the Pope, so that what has happened has happened. I am very sure though that this all occurred without the awareness of His Holiness, i.e. that he did not know or consent that anybody would be killed. However, I have known for a while that perhaps His Holiness would not have minded, or would have in fact appreciated and greatly liked a regime change in Florence.

So far, the letter seems amazingly sincere and straightforward; the writer wishes to establish his trustworthiness. Montefeltro claims that there would have been good grounds for the pope to complain about Lorenzo’s behavior, because of his recent interference in business between Church and city-states both in Città di Castello and in Montone. He even comes close to confessing his own participation in the plot:

Had I been told about this plot, it would not have been licit for me in any way to do anything but keep it to myself and secret, since I am mostly a soldier of the Pope and the King of Naples and being paid by their monies, which makes me loyal and obedient to them. Nor should there be anybody who thought differently, since I would be a bad man if I propagated something confidentially communicated to me by my patrons. I say this because some footsoldiers of mine went from Castello with Lorenzo Giustini, whom I had sent upon his request to deal with some troubles he had in his town, and I have his letter which I can show upon request. I am very sorry for what happened, but now I tell you that if some remedy is not found to re-establish things easily in their proper balance, it will not be too long before things might get so bad they will be beyond repair and lead all of Italy into war, a situation that is not generally desirable, nor a situation that I would want at all. Having suggested to your Magnificence the proper remedy for this situation, you have, God Willing, the power and means to take care of it.

Federico seems to have thought hard enough about the justification he would use in case the attack went wrong. But his partial denial also spells out his awareness of the plot. He claims that his concern is to restore the lost balance of power by pretending that nothing has really happened. In fact, his pragmatic, soldierly talk is deceptive: between the lines, he is saying, “Let’s deal with the consequences, no matter what the causes.”

Federico’s mention of Lorenzo Giustini’s request for troops to sort out “troubles” in his town of Città di Castello is a revealing touch of insincerity. Federico had bothered asking Giustini for a letter he could “show upon request” to discharge himself from any wrongdoing. But it was a lame alibi. Giustini was a trusted member of the Roman clan and the bearer of the golden chain for Federico’s son Guidobaldo that had sealed the deal with the pope’s emissary back in February. The captain from Castello had in fact been in command of the six hundred troops sent from Urbino. He had also prevented Bernardo Bandini, Giuliano’s killer, from being immediately captured and helped him flee toward the East.

The indirect evidence against Montefeltro provided by this letter might have been enough to close the case in history’s tribunal. But a much more interesting story lies ahead. Federico’s secretary sent to Cicco’s son Gian Giacomo a less openly aggressive letter, in which the Duke of Urbino’s awareness of certain plans (for regime change but not death) is conveyed in a slightly more nuanced form. Federico, in the words of his subordinate, did “not deny at all having known all these things for a while, that is, from the time when he was in Montone with his army.” Federico is quoted as having prudently voiced some concerns about Montesecco’s allegations against him. He is also said to have examined his “conscience” as a statesman and his “worldly honor” as a soldier, phrases pointing to the complex relationship with his two paying patrons. The secretary writes:

His Lordship says that in the beginning he tried to dissuade the King and the Pope from doing this deed for its evil and scandalous nature, but after seeing that this was taken badly and that the water was already running downhill he shut his mouth and his eyes, hoping and believing that the conclusion of his condotta with the League would sweeten the passions of some and would make them forget and throw aside this bestiality, mostly because they seemed to be so enthused about it. As you know, all the opposite has happened, since they have turned this condotta into a mercantile business, and under its banner they have committed this misdeed, and made him [the Duke] look like a beast, shaming him. He has relied on the Pope in order to justify himself to the King more strongly, but His Holiness has conferred on him the beautiful honor of shaming him.

One could almost sympathize with Federico’s irritation over the failed plan, but he also flatly denied that the condolence letter to Lorenzo contained anything reproachable or malicious. Responding to Cicco’s charge of having received news

from Florence that the letter written by the Duke of Urbino to the Magnificent Lorenzo contained a coda or conclusion which could be interpreted in bad terms, the Duke of Urbino says he marvels greatly, since he has written to Lorenzo nothing but good and that there is no part in his letter which does what you say.

The condolence message of May 1 had not gone unnoticed by the canny Lorenzo, and its insidious nature is now all too evident to the contemporary reader. Having failed to scare the Medici into silence, Montefeltro went on denying that his troops might have been spotted outside Florence. Here, the extent of Federico’s shamelessness is truly exceptional. He has his secretary write further to Gian Giacomo:

I reply that it could perhaps be the case that somebody with our uniform has been seen around, since many who wear it are not men of my Lord or hired by him, as it can be clearly noticed, but that there would have been some of the Lord’s country, that is, his soldiers or somebody else fighting for him. Rest assured that my Lord says that this is not the truth and that it will never be found out that he has been involved in any way in the aforementioned event.

Urbino, 13 May 1478.

P.S. Some merchants and other people of ours who were there at the time of this event in Florence have returned here; they report that it is true that in Florence it has been said that somebody was wearing the Duke of Urbino’s uniform, but then a comparison was made and it was found that it was not the one of the Duke of Urbino, and this is the actual truth.

DID FEDERICO ACTUALLY EXPECT to be believed? Or, like many mobsters on trial in our own time, was he just refusing to admit the evidence of facts? The rhetoric of truth is most frequently adopted by professional liars. Federico was using the double Montefeltro code, which Simonetta had learned to appreciate during the previous thirty-five years of dealing with the fox from Urbino.

Cicco knew that the situation called for speedy action rather than hypocritical indignation. The chancellor faced a difficult diplomatic challenge, one worthy of his Machiavellian and “most excellent” brain. He did not hide from himself that this was the point of no return in his longstanding friendship with Federico, and, as usual, he acted swiftly and secretly. In a letter dated May 9, he had already implored Lorenzo to heavily guard himself, even though this might be a source of public gossip. Without naming names, Cicco then alluded to Federico as one of the various “authors” and “instigators” of the “horrific deed.” Whether these people only passively knew about, or actively participated in, the “betrayal,” in the event of a counterattack, warned Cicco, it was best in any case to pretend (the verb fingere is added by Cicco in the original draft) not to have “seen” or “understood” their role in the deed, “passing everything under silence and in the utmost secrecy.”

Sometimes, playing dumb is the smartest political maneuver. Cicco had firsthand knowledge of this truth, having learned it the hard way in his long career under Francesco Sforza, a master of manipulation. One of the main rules in the game was never to let your enemy find out your true intentions. In fact, Cicco had already started playing the game and acted upon the first reports before Federico’s letter to him of May 8. He personally wrote a sample letter addressed to Federico on Florence’s behalf and shipped it to Lorenzo, who liked it “immensely,” had it copied “word by word,” and sent to Urbino and Rome, in order to suspend at once all the bargaining around Federico’s stipends. Lorenzo’s reply of May 12 to Cicco contains all the self-deprecating sarcasm that one might expect from him:

the writing of the Milanese State…appears to me loving and prudent…I thank you for the affection, great prudence, grave counsel…I know well, given both the nature of those who offend in general and the particular conditions of those who have offended me, that we need to keep our eyes wide open and not to trust our innocence, since if that were enough, what happened would not have happened. I hope to God, who this time has saved me miraculously, that perhaps I will be worthy of His pity, so that He will have saved me for a purpose.

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

LORENZO’S SELF-PITY AND PLEA TO GOD WERE INDEED APPROPRIATE. Keeping quiet in the poisoned atmosphere that followed the Pazzi conspiracy was almost impossible. Florentine ambassadors and merchants in Rome were threatened by the pope with jail or murder, in open disregard of treaties between the states. Sixtus was furious about the arrest in Florence, shortly after the attacks, of his young nephew Cardinal Raffaele Riario, who was held captive for about a month. After a series of intense negotiations, the cardinal was finally released. But the irate pontiff excommunicated Lorenzo and indicted the entire city of Florence under the pretext that its citizens and officials had hanged members of the clergy, including the archbishop of Pisa and the apostolic secretary Antonio Maffei of Volterra, Lorenzo’s attacker. The only way for the Florentines to save their souls was to get rid of the God-defying Medici leader, or at least so said the pope.

Cardinal Riario was released from prison on June 7. The Florentine magistrates and many citizens accompanied him on his walk from the Palazzo Vecchio to the Annunziata church. He was “in dread of being killed by the populace,” as the contemporary diarist Luca Landucci noted. One can only imagine what the angry Florentine mob, notoriously loudmouthed, shouted at the pope’s young nephew. He was escorted by forty guards but the terror he experienced that day would remain with him for the rest of his life: a legend describes him as permanently pale. It was on that very day, as Landucci records, that “the Pope excommunicated us” (that is, the Florentine people). The shameful papal bull had in fact been published almost a week earlier, on June 1, but its terrible content was not immediately divulged to the people.

On June 12, once his way out was secured, Cardinal Riario finally left Florence. The most influential citizens called for an immediate emergency meeting. Lorenzo knew this was the moment of truth: it was also the supreme test of his statesmanship and of the cohesion of the regime. He gave a memorable speech, reported by Giovanni di Carlo in the History of His Times. Giovanni began his account by describing the three civic parties in attendance. At the meeting, the angriest citizens blamed the pope and his priests, who must not only have been aware of the plot but also involved in it. Others, Giovanni tells us, expressed sorrow and some pushed for a diplomatic solution by sending envoys to the pope and the King of Naples to avoid war. At that point, Lorenzo rose to his feet and waited for silence in the crowd. Then he spoke in his nasal voice:

On this public occasion, Sworn Fathers, if I were not struck by a private mourning in my soul and body, perhaps I would talk at more length, deploring it along with you, acting like an eloquent orator and taking on the role of the good citizen. However, the indignity and impiety of the case burdens and hampers me. Words fail me, and my teeth impede the movements of my tongue.

It is customary for mortal men, when they experience something bad or evil, to seek refuge with their relatives, friends, and in extreme need with priests and holy bishops who, if unable to provide help, can at least alleviate pain and ease sadness with their words. As the philosopher says, we are born not only for ourselves, but also for our fatherland, for our countrymen and even more for our neighbors, in order to assist them and favor them as much as we can. For the same reason, matrimonies, pacts and agreements are made in every business, whether civil or military, especially at a time so full of troubles and calamities.

Lorenzo was appealing to the strong sense of the Christian and communal bonds among the Florentines. In the most charged moment of what in effect was his survival speech, he addressed himself to his dead sibling, in a low, moving voice:

Dearest brother, whose wounds are still under my eyes, how should I talk about your undeserved death? Perhaps I should look for priests or churchmen, who were not only present at this horror, but even participated in it? In pagan Rome, divine temples used to be refuges for safety, whereas in the greatest Christian temple consecrated to God my brother was killed and I was hit, pulling through by a hair from the hands of impious killers…

Lately, I have been reconsidering my situation, and I think my brother’s fate is preferable to mine. I have preserved my life, which turns out to be damaging for you and for the city.

Sworn Fathers, you are my friends. I owe you everything. All citizens must place the common before the private good, but I more than anyone else, as the one who has received from you and the fatherland more and greater benefits. Therefore, use my wealth as you please, I am ready to go into exile or to die. I am ready to go off to the farthest islands on earth or migrate from this life altogether. You have fed me and raised me, and you can take everything from me. If you find it is of use to the Republic, kill me with your own hands, since I am in your hands anyway, as are my children and my wife. If you want, let them have the same fate as mine, the most honest death. It will be to the eternal decency and praise of yours that you have submitted us to exile or death for the good and safety of the people and city. For the state and the city and the people, there would be no better divine and more tolerable goodness than to let us die at your hands—the hands of my parents, my citizens and friends. But my brother was innocent and nonetheless he was killed in the spring of his life…If they attacked him in our great and famous church, during the celebration of divine rites, can you trust the Pope’s most secular promises?…

So, decide of me and my children what you think is best for the welfare of the Republic, and whatever your decision I will consider it the best and safest.

In his Florentine Histories, Machiavelli reports that the assembled audience could not hold back tears. No such melodramatic outcome is recorded by Giovanni di Carlo, who was present at the oration and wrote it down only a couple of years after it was pronounced. His version is therefore slightly more reliable than the one reinvented by Machiavelli half a century later. And while, in Machiavelli, the political reasoning that followed this emotionally charged moment remained in Lorenzo’s speech, Giovanni left it to an unnamed citizen. But then Machiavelli’s Florentine Histories were commissioned by Pope Clement VII, son of Giuliano de’ Medici, and to present Lorenzo performing a one-man show of political bravura was appropriate to a Medici pope. For Machiavelli, Lorenzo was being an astute politician when he fashioned himself as a sacrificial lamb offering to give away all his power and even his life: he was really aiming to preserve his position and his family, with all his money and influence intact.

In Giovanni’s account, on the other hand, the nameless Florentine orator who stood up after Lorenzo’s speech mentioned the approaching “Urbino phalanx,” the scary proximity of Federico’s army, and then launched into a general wake-up call to the sleeping city of Florence. After listing a series of popular proverbs, such as “only the good fighter gets a good peace” and “don’t let the wolves in among the sheep,” he asked a rhetorical question: “Who would think that a wolf dressed in sheep’s clothing can be anything other than a wolf?” (a clear reference to Sixtus, who had shown himself more of a wolf than a sheep, or shepherd for that matter). Eventually, the speaker came to his point:

They want to invade the whole city. They are not after Lorenzo and his acolytes, but they want to put a yoke on the entire state. If they wanted only Lorenzo, why would they move so many troops and occupy our public buildings?…It is an extreme measure for Popes to call on secular armies…I know for a fact I am hated by priests, who lack piety and religion and respect for God, and who are greedy and corrupt…Let’s send envoys, even clerics, to the farthest corners of the earth to get money to fight this war. If we should lose, at least we will lose not like nervous women, but like strong men…In such extraordinary circumstances as ours, it is not necessary to respect the status quo.

Lorenzo made a masterly use of counterpropaganda. To fight the war of words against Sixtus IV, he hired an army of lawyers who argued that the crimes against clergy members had been committed in self-defense. How indeed could the pope forget that the archbishop of Pisa had attempted, weapons in hand, to seize the Palazzo Vecchio? Who could deny that the plotters had paid killers to attack Florentine citizens in the main cathedral? The case for the excommunication of Florence hinged entirely on the faint assumption that Sixtus was acting in good faith. But after the plot, it was far easier to claim that the pope was a tyrant and a crook.

THE BLOODY BIBLE

THE FLORENTINES REACTED TO THE POPE’S THREAT WITH A most violent pamphlet. Longtime Medici supporter Gentile Becchi—who had been the brothers’ tutor before becoming bishop of Arezzo—took charge of the response to the excommunication: in the fiery, sacrilegious Florentine Synodus, he reported that all the Tuscan bishops had gathered and attacked the pope as an arch-assassin, “Vicar of the Devil” and “Pimp of the Church.” This counterexcommunication was meant to ruin the Holy See’s reputation in Italy and across the Alps.

Sixtus IV saw the dangers involved in this defamatory campaign and commissioned a quickly printed attack for circulation in Germany, France, and other countries. This document, entitled Dissension Arisen Between the Holy Pontiff and the Florentines, survives in only a handful of copies around the world, and it has never been studied until now. The anonymous author uses all the nasty arguments he can find to show up Lorenzo’s weakness, mocking him for being incapable of opposing the military might of King Ferrante of Naples, and at some point bursts out: “If God is with us, who is against us?” The use of Mark’s Gospel is a powerful piece of counterpropaganda from the righteous defender of the faith. The Dissension lists all the Florentine misdeeds, discredits the “heretical and sodomitical Synodus” (its author, Gentile Becchi, bishop of Arezzo, was rumored to be homosexual), and avoids mentioning Giuliano, until suddenly declaring that he died “by God’s will” and because of his wretched life. Then it offers a twisted biography of Lorenzo as an early apprentice to the ways of evil and tyranny.

Gentile Becchi had plenty of motivation. He was a native of Urbino, and his family possessions were being seized at the duke’s will, even as the excommunication against the Florentines was destroying his revenue as bishop of Arezzo. And Arezzo was the town southwest of Gubbio that would likely have been awarded to Federico if the Pazzi operation had gone well. Without mincing words, in his typically biting style, Becchi wrote to Federico’s secretary: “You say to me that I should become like the angel of peace. Who is waging war, you or we, who have been cut into pieces in church? Attacked by a huge army, we even have to feel guilty. If you asked anybody involved: ‘What have we done against you?,’ what would you answer in good faith?”

In the midst of this theological turmoil, Federico was absorbed by a personal, seemingly petty concern. Over the preceding years he had invested several thousand florins in the making of a gorgeously illuminated edition of the second half of the Bible (from the Book of Job to Revelation), which he had commissioned from the most famous manuscript dealer of the time, Vespasiano da Bisticci. Vespasiano, who ran the largest workshop in Florence, was also a writer in his own right, and left us a series of biographical medallions of the illustrious men of his day. Unsurprisingly, he had only praise for Federico’s virtues as a soldier and as a humanist, and for his expensive taste in richly decorated books.

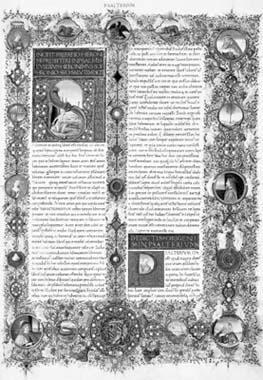

The opening page of the second volume of the Montefeltro Bible, produced in Florence and finished on June 12, 1478.

The opening page of the second volume of the Montefeltro Bible, produced in Florence and finished on June 12, 1478.

The Bible was to be the jewel in Federico’s sumptuous collection, and the duke could not bear the thought of possibly losing it to the Florentines. The huge manuscript had been completed on June 12, the day of Lorenzo’s survival speech. It was dedicated to the “Church’s Commander, engaged in defending the Christian religion no less than adorning it.” Lorenzo, the “Son of Iniquity and Perdition” according to Sixtus IV’s bull, must have appreciated the irony of the situation: the pope’s captain depended on his excommunicated enemy to release the most precious Bible ever made. But Lorenzo politely had the lavish folio sent to Federico.

On June 21 Federico thanked Lorenzo for his kindness, but by then war planning was already under way. A Florentine agent in Urbino informed Lorenzo that the duke was preparing for battle, although in late June he was still recovering from the November injury to his leg. Federico had an “ingenious” saddle-chair built to allow him to ride with the injured leg around his horse’s neck. The horse was paraded daily in the streets of Urbino to demonstrate that the duke intended to keep his promise to lead his own troops. But in a confidential letter, the agent wrote to Lorenzo that, one day, while Federico had proudly mounted his horse, he had not been able to restrain muffled cries upon dismounting. The duke was reportedly furious that his moment of weakness had been witnessed by Lorenzo’s man.

According to the courtly poem written by Giovanni Santi, the mission of the unnamed Florentine envoy in Urbino had been to complain unofficially to Federico about his complicit silence about the conspiracy and to question his moral integrity. Apparently, Federico had replied to the envoy’s line of questioning with the same arguments he had used earlier in the letter to Cicco: it is not reasonable to alert an enemy (such as Lorenzo) and offend your good patrons, so if he had known anything, he would have kept his mouth shut. In the past he had had many offers from people willing to discreetly rid him of his foes (such as his late archenemy Sigismondo Malatesta), but he would rather fight a “nasty war” even if he could not even stand on his feet.

In the meantime, Federico’s papal condotta was finally confirmed and paid in full, making the loss of Florentine and Milanese money more bearable. It amounted to the fantastic sum of 77,000 ducats for commanding four hundred men-at-arms and four hundred foot soldiers. The cash was brought to Federico by the pope’s usual intermediary, Lorenzo Giustini. After their three-hour-long secret meeting, rumors spread in Urbino that everybody in the ducal army would be paid immediately: fifteen ducats to the cavalrymen and eight ducats to the foot soldiers. The generous and immediate pay to 370 huomini d’arme (men-at-arms) showed the duke’s readiness. There was still some debate about whether his recovery would be speedy enough for him to command his troops. Federico also put in place some extreme security measures: he had left his palace only twice in June, each time surrounded by crossbowmen carrying swords and Bolognese machetes, and the gates were guarded so closely that no one was permitted to enter. Paranoia and fear of being killed were unusual characteristics for a professional soldier, especially a mercenary like Federico. It was not a pretty sight.

The spy who provided this detailed information was Matteo Contugi, a calligrapher from Volterra who had been hired in Urbino to copy some of the most beautiful manuscripts in the famous Montefeltro Library. This is only one of many entertaining reports from this educated and clever man, who held a respectable post in the court of Urbino. He was above any suspicion there, although since he was from Volterra, the city that the duke had sacked, Contugi had good reason to hold a secret grudge against him.

Contugi added that Federico had also received some gifts from Cicco. They were probably wrapped into cheese shapes, so that nobody would see or steal them. The well-informed agent writes that they consisted of a rich cover for a horse’s head, a beautiful helmet, and a sword. One may wonder why Cicco was bothering with these gifts. Apparently, he was still hoping that the war machine would stop, and that Federico would switch horses.

In early July 1478, Cicco wrote to Lorenzo that Florence and Milan were unum velle et unum nolle (united in willing and unwilling) and that they would be made or unmade together. When Lorenzo received this letter, the excommunicated but still devout Florentines were celebrating the delayed Feast of San Giovanni (which was really on June 25) “as if it had been the real day.” The people tried to find some relief and distraction in the usual passatempi. But just a week later, on July 13, the city had to wake up to the bitter reality: the King of Naples had sent a herald with the papal ultimatum. The most influential citizens of Florence agreed that expelling Lorenzo from the city would not solve their problems. And so the Pazzi war began.