8

LIVES AT STAKE

WARFARE IN RENAISSANCE ITALY WAS OFTEN MORE A MATTER OF SHREWDNESS THAN BRAVERY. The rules of engagement were to avoid confrontation and play with strategic delays—unless the use of brutal force became necessary. Federico did not hesitate to resort to violence. He was a steadfast commander and also an expert in military technology. His engineers and architects were the best brains in Italy. His tactics included the use of devastating artillery devices as well as the construction of strongholds.

In his youth he had displayed his military skills when he took by a nocturnal attack the Castle of San Leo, a virtually impregnable fortress built on a tall, precipitous rock. Federico had some long ladders made, and his men successfully climbed all the way to the top—when they were having second thoughts midway, he threatened to pull the ladders away. This act of bravado had persuaded Federico’s archenemy Sigismondo Malatesta, the lord of neighboring Rimini, to accept a truce with Urbino.

In his dialogue on The Art of War as much as in his Florentine Histories, Machiavelli poked fun at the virtually bloodless battles featured in the last decades of the fifteenth century. The main purpose of fighting, for largely mercenary troops, was in fact to loot more than to win. And the civilian population, as usual, would pay the highest price. One should keep that in mind while reading this brief account of the Pazzi war, which lasted almost two years—that is, two springs and summers, until the fall of 1479.

The army hired by Florence and Milan against Pope Sixtus IV and King Ferrante of Naples seemed strong at first, but internal feuds weakened its power. Since the start, Lorenzo and Cicco had employed two expensive mercenary captains, Ercole d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, and young Federico Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, but the two fought over leadership, slowing down their own military operations. They ended up pillaging each other’s military camps. This was a perfect environment for a ruthless veteran like the Duke of Urbino, who took advantage of every opportunity offered to him by his enemies.

The battles of the Pazzi war were relatively bloodless for the armies, but the war has remained notorious as a testing ground for innovative siege weapons, including chemical artillery. Federico was particularly keen on new, deadly devices. He boasted in a letter to Matthias Corvinus, king of Hungary, about his five field-pieces, called bombards, distinguished by startling names such as the Cruel, the Desperate, the Victory, Ruin, None of Your Jaw. One of the largest consisted of two portions weighing 14,000 and 11,000 pounds each. It discharged balls of stone, varying in weight from 370 to 380 pounds. Federico was eager to see it at work.

A DIRTY FIGHT

ON JULY 25, AN ANGRY AND ANXIOUS POPE SIXTUS IV WROTE in his own hand to Federico a letter half in inelegant Latin, half in uncultivated Italian:

We trust that God, whose honour and glory are at stake, will grant you victory in everything, especially as our intentions are straightforward and just. For we make war on no one save that ungrateful, excommu nicated and heretical Lorenzo de’ Medici, and we pray to God to punish him for his infamous acts, and to you as God’s minister deputed to avenge the wrongs he has iniquitously and without cause committed against God and his Church, with such ingratitude that the fountain of infinite love has been dried up.

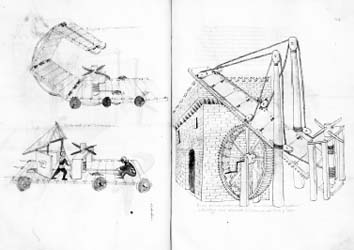

War machine, in Roberto Valturio’s volume, De Re Militari. This work was composed for Federico da Montefeltro’s enemy Sigismondo Malatesta, lord of Rimini. Federico eagerly studied the military techniques of his adversary.

War machine, in Roberto Valturio’s volume, De Re Militari. This work was composed for Federico da Montefeltro’s enemy Sigismondo Malatesta, lord of Rimini. Federico eagerly studied the military techniques of his adversary.

The Duke of Urbino hardly needed the pope’s blessing to be encouraged in his bellicose enterprises. Before the beginning of the hostilities, Federico—who was still recovering from his leg wound—predicted in a speech to his soldiers, who were eager to loot rich prey on Tuscan soil, that within three years the bold Florentines would be reduced to nothing. “Naked and on their knees,” embellished Giovanni Santi, imitating Federico’s oratory style in the poem he wrote to celebrate the captain’s successes, “they will come to plead for mercy and will lower the lofty pretenses of their ancient freedom (if one can still call it that, I do not know). They will be brought down to their knees for a long time, and their ancient glory will be hopelessly dressed in a mourning suit!”

The prose of war was even more disagreeable than these gloomy, versified prophecies. When in the summer of 1478 a plague struck Tuscany, the Duke of Urbino reportedly said that the disease achieved what he had not yet hoped to obtain through war, wiping out most of the men. Federico’s ally Alfonso of Aragon, who led the Neapolitan troops, was renowned for his ferocity on the battlefield. A Florentine official who was trying to resist Alfonso’s siege in Castellina, in the Chianti valley, sent a message to him complaining that he had found some poisoned arrows thrown at the defenders, and he warned Alfonso that if that continued he would attach toxic substances to the Tuscan artillery.

But the relationship between Federico, now old and crippled, and the younger, impulsive Alfonso was not all that smooth. The malicious calligrapher-turned-spy Contugi reports that the allied Neapolitan troops nicknamed the Duke of Urbino Cain: the rumors that Federico was behind the killing of his stepbrother Oddantonio were still very much alive thirty-four years after he had seized power over the Montefeltro region. In some ways, the troops were justified: over the decades, the duke had remained as ruthless a field commander as he was a politician, and the Pazzi war presented him with a good opportunity to show off his military prowess.

The true soldier knows when he must use force and when he must resort to fraud—that is, when to be a lion and when to be a fox. And Federico was a true soldier. The first serious strategic challenge that he faced was the siege of the virtually impregnable Florentine Castle of Sansavino, not far from Siena. At a point when his camp was floating in mud and his army was demoralized, he delivered such a galvanizing speech that he pulled his forces back together. According to Santi, he paraded “more than a thousand horses” and his famous bombards in front of the castle’s walls, just to frighten the besieged. Then he obtained a general ceasefire, approved by Ercole d’Este, commander in chief of the Florentine and Milanese army, pretending that he had not sought it. During the eight-day ceasefire Federico received money and ammunition from Rome and fresh crossbowmen from Urbino. As soon as the hostilities were about to resume, he made such a show of force that he did not need to use it against Sansavino. The castle’s captain simply resigned, keys in hand. “Sometimes a captain needs to be a lion, sometimes a fox”—Santi had him say in his celebratory poem, adding: “A single eye has seen more than a hundred-thousand!” Federico was amused by the astute Florentines’ outcry that they had been tricked by a shrewdness greater than theirs. This dirty war quickly began to wear down the Florentine forces and their close Milanese allies.

CICCO’S WAR

LORENZO WAS NOT THE ONLY TARGET OF THE PAZZI WAR. FOR Roberto da Sanseverino and the exiled Sforza brothers Sforza Maria and Ludovico, who had naturally sided with the enemies of Florence, Cicco was still enemy number one. Cicco’s age was taking its toll, and he had begun to resemble other powerful gout-stricken figures such as Pius II, or Piero de’ Medici, who had often governed from their bed. With the incompetent Duchess Bona and the child-duke Gian Galeazzo utterly incapable of governing, and with Cicco struggling with his health, Milan was particularly vulnerable.

Since his exile in May 1477 the hot-tempered condottiere Roberto da Sanseverino had been restlessly pursuing his vengeful return to Milan. He had visited the king of France to look for foreign support, and then had conducted bold actions of disturbance aimed at weakening the regency. In early August 1478, for example, he helped Genoa in its second rebellion against Milan and scored his first major victory. The Milanese were at a disadvantage in any case: unlike the punitive expedition that the Sforza brothers and cousin had conducted against Genoa in March 1477, this one had no strong military leadership. Against the large ducal army sent by the regency, the former captain and now foe Roberto made the canniest use of the Genoese defensive strongholds, which he himself had attacked once before. He easily humiliated the Milanese troops and sent many of them back half-naked, after seizing their weapons and armor. The fiasco was a big blow to the credibility of the regency in Milan.

The growing isolation of Lorenzo and Cicco brought about an increasing tension between the allies. On December 29, 1478, Cicco wrote a compelling letter to Lorenzo stating that their enemies clearly believed that the elimination of them both would be a complete success. Although Cicco’s library was filled with secular, humanistic books, in official documents he often resorted to religious texts, quoting lines especially from the Gospel of Matthew: he compared the hatred of his own adversaries to the prophecy of the blood that would befall the architects of Christ’s condemnation, and his citing the response given to Peter when Christ walked on water—“Oh, ye of little faith…”—signaled his awareness of the imminent danger in which he lived. In this most tragic moment of his career, Cicco saw himself walking in Christ’s footsteps, and in doing so, he assigned Lorenzo the role of Peter.

Pope Sixtus IV would have been amused by the pious references made by his political enemies. The pope and the King of Naples, fully aware of the fact that Milanese money and its army were keeping Lorenzo afloat, decided to create as much trouble as possible at the borders of the Sforza duchy. They sent a man called Prospero Medici (no relation), an agent provocateur who hated Cicco, to buy out and rouse the Swiss mercenaries against the regency. These wild and greedy troops crossed the Alps and penetrated the Milanese state, raiding mountain farms with a violence that was, as Cicco’s son Gian Giacomo Simonetta wrote to Lorenzo in a letter dated January 9, 1479, “scarier than that of the Turks” (the Turks were permanently on the verge of attacking the peninsula, and in fact they would invade its southern tip in 1481). Some Sforza soldiers were dispatched on a retaliating mission, but they were caught in a bloody ambush and humiliated in a serious debacle. This earned the Swiss fighters a good name, and they eventually became the official bodyguards of the popes (from 1506, under Julius II).

Florence and Milan were also weakening financially. In Florence, Lorenzo had a hard time extracting taxes from his citizens, so much so that police officials had to be sent to people’s houses to collect them. In Milan, the destabilizing wars sucked up all the state funds. In his January 22 letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici, Gian Giacomo Simonetta reported that since Galeazzo’s death the Milanese duchy had already spent the mind-boggling sum of 1.6 million ducats on security and wars.

Access to the ducal treasury, which contained over two million ducats, was a privilege of the duchess alone. Therefore, the governors were forced on a daily basis to borrow cash from moneylenders at a high interest rate, and in order to guarantee a repayment they had to compromise all the present and future state tax revenues. To avoid bankruptcy, Cicco had to accelerate negotiations toward a peace process. He probably had too much faith in its feasibility. He did manage to have a treaty between Florence, Milan, and Naples drafted in June 1479, but it came too late.

Back in the summer of 1478 King Ferrante had sent to Bona and young Duke Gian Galeazzo Sforza a long, nasty invective against regent Cicco, who was, he said, “forgetful of fortune and of himself” and the “dictator of your letters.” Ferrante did not actually mention Cicco’s name, referring to him instead as the Milanese Dictator; the biting and vicious double meaning was perhaps too subtle. But in a letter dated January 12, 1479, Ferrante explicitly expressed his hatred for Cicco, calling him a “worm coming from the earth” (as a native of Calabria, Cicco had been born a subject of the Aragonese king). Such statements were designed to create a wedge between Duchess Bona and the regent, and to convince her that he was untrustworthy.

SFORZA MARIA AND LUDOVICO had been exiled by Cicco after the attempted coup of May 1477. Since then, the two troublemakers—who had also been suspected of being behind Duke Galeazzo’s murder—had been kept relatively quiet by the duchess’s threat that they would lose their allowance if they caused any trouble. Sforza Maria, Duke of Bari, was first exiled to his remote duchy in Puglia, at the southeastern tip of Italy. He then managed to move from there to Naples, under the wing of King Ferrante of Aragon. And it was from Naples, in January 1479, that Sforza Maria took off by sea in a few galleons eagerly provided by Ferrante, eventually to fight his way back into Milan.

Ludovico Sforza had been confined in Pisa, having managed to remain on neutral terms with Lorenzo. He then joined his brother on the coast of northern Tuscany and they reunited outside Genoa with restless Roberto da Sanseverino, who had not ceased for a minute to create military mayhem for the Milanese government, by siding with any potential insurgents and raiding the Lombard countryside with his troops. The three exiles were aiming to discredit Cicco as a usurper of the duchess’s trust.

Supported by their powerful Aragon ally, Roberto and the Sforza brothers made several attacks against the regency. Roberto started marching toward Milan; surprisingly enough, he did not find any real opposition on his way. Many ducal towns surrendered in the name of the Sforza heritage, denied them by the evil governor Cicco. Unlike Roberto, though, the brothers were not trained for the hardship of military life. Sforza Maria fell ill in the summer of 1479, and died in late July “because of his unbelievable fatness.” But the only other legitimate Sforza, Ludovico, also known as Il Moro, the Moor, for his dark complexion, showed the strength of his survival instinct.

“THIS NEW STATE IS LIKE GLASS OR A SPIDER WEB…”

DUCHESS BONA, GALEAZZO’S MERRY WIDOW, HAD BECOME even more ineffective in state matters under the influence of her lover Antonio Tassino, a young and handsome man. He was jealous of Cicco’s power and persuaded her to readmit her exiled brother-in-law, Ludovico, with whom he had had a confidential correspondence not intercepted by any spy. It was a sign that Cicco was losing his grip. On the night of September 7, 1479, Ludovico secretly entered the Sforza castle in Milan, via the large park at the back. He was welcomed by Duchess Bona and was lodged in a beautiful room. All she wanted, admittedly, was vivere allegramente, to live without any worry. It was a very naïve hope. She and Ludovico agreed on a peaceful reentry for himself and Roberto da Sanseverino.

As soon as Cicco realized what was going on, he went to Bona and told her that she had made the worst mistake of her life: “Madonna, in little time I will lose my head, and you will lose your state.” These words, later reported by many historians, would reveal themselves to be prophetic. There was no point in hiding in one of the many secret chambers of the castle, which had provided a safe haven for the chancellor for so many years. Cicco patiently awaited his fate. During the night of September 10, Cicco and his brother Giovanni were captured by ducal guards and hidden in a carriage escorted by one hundred cavalry. They were brought to the dungeons of the Castle of Pavia, near Milan. Their palaces in both countryside and town were left exposed to the looting of the people. A large number of soldiers had to be sent into the streets in order to prevent any more public unrest.

Cicco’s enemies were jubilant. Sixtus IV and Girolamo Riario in Rome and King Ferrante in Naples all expressed their satisfaction at the arrests. Now that Milan had been liberated from the “usurper’s tyranny,” Florence would soon follow. Federico, however, did not send any congratulatory letter to Bona. Just two years before, in the summer of 1477, he himself had warned the chancellor against falling into an abyss of “dangerous dangers.” That the downfall had come to pass did not thrill him. After all, they had never been enemies. He also realized that the new regents were rather unreliable. “These Sforza heirs”—as Mantuan ambassador Zaccaria Saggi put it—“play hard at being inscrutable.” The traditional allies of Milan would come to realize this all too soon.

When Lorenzo received the news about Cicco’s imprisonment, he immediately wrote to Ludovico Sforza, appealing to their long-standing friendship. Without ever mentioning Cicco, he emphasized that he himself had never done anything against Ludovico and had actually been helpful to him during his exile in Pisa. But Il Moro’s response was supremely noncommittal. Although formally deprived of any power or title, Ludovico was already acting like a duke-to-be, garnishing his chancellery’s letters with solemn and empty words. He immediately created a clique of courtiers who would praise and please him. While the Simonetta brothers were rotting in the dungeons of Pavia, he asked that Giovanni Simonetta’s Life of Francesco Sforza be read aloud to him, chapter by chapter. This elegant Latin biography celebrated the glorious deeds of Ludovico’s father, who would remain an unattainable model of virtue for his ambitious son. Zaccaria Saggi was startled at the “new things” that were unfolding in Milan, and commented: “This new State is like glass or a spider web…”

Lorenzo realized how dangerously defenseless he was without the Milanese protection. He urgently dispatched the Florentine poet Luigi Pulci to meet Roberto da Sanseverino in Milan, just as he had done in February 1477, under very different circumstances. Roberto was requesting that the duchess pay him the money she owed him for the services he had performed before his exile and that she return to him the properties he had lost since then. He also requested that this time around his stipend should be not equal to but higher than that of Federico da Montefeltro. Pulci’s mission in Milan was not to deal with such economic details, however. A plan of attack against Tuscany was afoot, and Pulci had to steer the greedy condottiere away from it.

Florence was in fear—and justifiably so, as is made clear in a series of partially coded letters that have recently come to light. Count Riario had sent to Milan his envoy Gian Francesco da Tolentino, the captain who had been in command of the papal troops enlisted to seize Florence after the botched Pazzi conspiracy. Tolentino’s semiciphered letters, written during the month of October 1479 from Milan, contain some shocking information. Tolentino reported with sadistic enjoyment that Cicco was about to be tortured (only his old age and bad health had prevented him from being tormented until then, though his military advisor Orfeo da Ricavo had not had such luck). Then he added that the usual source, Lorenzo Giustini, had informed him that the Duke of Urbino thought it was time to tighten the rope around Lorenzo’s neck. Tolentino also laid out for Riario a plan to raid the rich Tuscan villas of the Mugello valley:

We will sack all those palaces and we will raise terror in Florence…For God’s sake, my lord! It is the fear of being touched in their properties that really throws that people upside down! Please consult the Duke of Urbino on this matter and inform me as soon as possible. Once I put these troops together I will go to Imola to take care of the business…[words in italics are ciphered in the original]

The same mercenaries who had participated in the failed Pazzi operation still hoped to redeem themselves with a spectacularly violent exploit. If only they could manage to get the impetuous Roberto da Sanseverino on board, their plan would finally go through. Pulci, ever the buffoon, somehow managed to dissuade Roberto from leaving Milan at such a perilous juncture, just at the time when Ludovico was gaining momentum: the poet might have reminded the condottiere of the many treacheries that Gano, the archcourtier in his chivalric poem Morgante, had been performing in the absence of the great Orlando, the bravest of all of Charlemagne’s paladins.

SEIZING THE MOMENT

IN THE MEANTIME, ANOTHER VALIANT SOLDIER WAS ENJOYING the fruits of his successes. Thanks to his ruthless and shrewd strategies, Federico had seized all the key Florentine fortresses, Castel Sansavino, Poggio Imperiale, and Colle Val d’Elsa (this last bastion fell on November 13, after weeks of murderous artillery fire). Now that he dominated the Tuscan territory, it would have seemed easy enough to seize its flourishing capital. Unexpectedly, though, he decided against the enterprise. One biographer of Federico reports the eloquent speech he addressed to Alfonso of Aragon and his troops, advising them not to attack Florence:

Willingly, O Lord, would I go along with the opinion of those who advise you, if I were not still crippled, and since they proceed with reason and prudence and consider the beginnings and ends of things—there is nobody with so little intellect who would not judge that it is right, at first sight, to enjoy victory and to silence whoever said that such a great, juicy occasion should be neglected. What would be easier than to march in at full speed, enter the city with all our forces, end the fight and obtain at once what has been so talked about? This would indeed be the ideal end to a war. But let us please consider the downsides: how could we stop the soldiers, libidinous and eager from the fresh victory, thirsty of prey both by nature and by custom, to sack, pillage and destroy that delightful countryside? Would they listen to any order or command? And even if they were obedient, and follow the orders, what then? Is Roberto Malatesta, the young and fiery captain hired by the Florentines, that far away? Does he not have enough troops to give us trouble? Does he not wait for any little opportunity to double his victories, and acquire for himself the title of liberator and defender of Florence?

But even if we do manage to control the city, and assuming that nobody falls short of his duty, when we find ourselves among so many enemy strongholds in a foreign country, won’t everything be full of dangers, and suspicions? Will our adversaries behind our backs go to sleep, and give us the comfort of living, and of fighting? We will be closed in on every side, and besieged while we believe to be besieging. Our enemies will be laughing at our expense, shaming us, and we will be doomed more by distress and hunger than by swords or by their forces. Haste makes waste, so if I am not mistaken it can only be a good thing to consider this matter prudently, before rushing into such an important, dangerous resolution.

This impressive piece of rhetoric might have been entirely fabricated by a complaisant biographer. But even assuming that there is no historical truth to it, the oration contains strategic wisdom about occupying foreign and unwelcoming states that is still valid today. It also shows that when Federico agreed to contribute to the conspiracy against the Medici, he had been banking on popular support for the conspirators’ party, which would have allowed his troops to control the city without too much bloodshed. In a way, he had been preparing himself to become the savior of Florence. But things had turned out very differently. Here was another opportunity to attack the city, and if Federico refused to take it, that was perhaps because he did not want to turn Florence into another Volterra. Certainly his legacy as a lover of studia humanitatis would have been forever tarnished by a sack of Florence—and he must have realized that. Was it possible that, at the time of the Pazzi conspiracy, he had agreed to send in his troops against Lorenzo in order to prevent the pillaging of the beautiful city that he wanted to control and the destruction of all things he held dear?

Another biographer of Montefeltro wrote about a “stratagem used by Federico against the Medici” during the Pazzi war: “In order to make them look suspicious to their state, he ordered that all of their possessions be safeguarded under the most severe punishments. Although the citizens could not do anything against this provision, since the Medici were very powerful, the rulers of Florence fell under suspicion in that city so naturally suspicious. It is no surprise, then, that after Federico’s death Lorenzo blamed this excellent captain.”

Ultimately, Federico was a strategic thinker who could play both sides of a chess game. He knew that an occupying army could successfully execute a regime change if it was perceived by the population as a liberator rather than an invader. Deterrence and threat worked in its favor, not violence and aggression. Federico also knew that he would achieve his ultimate goal of ridding Florence of Lorenzo not by occupying the city—aggression had failed once—but by forcibly undermining Lorenzo’s authority from without. Federico was killing Lorenzo by a slow death, in some ways perhaps more painful than the one that was inflicted on his brother. Or perhaps his inaction was another sinister oblique message to the Florentine leader. Politics is all about seizing the moment: new opportunities open up new scenarios for the Machiavellian mind.

EVIDENCE OF FEDERICO’S shifting plans comes from the confession made by the jailed Cola Montano, the humanist and “teacher of evil” who had indoctrinated the killers of the Duke of Milan. Montano, caught years later while he was engineering yet another conspiracy against Lorenzo—he was swiftly put on trial by Florentine officials and hanged for treason in March 1482—recounted fully his participation in the Pazzi war, recalling some key conversations among the fighters.

Having left Urbino with Federico in July 1478, Montano followed him during the early stages of the Tuscan campaign. When he informed Federico that Pistoia (a city southeast of Florence that functioned as one of the key bastions of its defense) was ready to surrender, the Duke of Urbino reportedly said that this would end the war and annihilate Florentine power. According to Montano, Federico was not enthused by such a quick triumph, since he wanted Florence “to be downsized, not destroyed altogether.”

Both Count Riario and Lorenzo Giustini told Montano that Arezzo (the southeastern bastion of the Florentine state, but also the southwestern doorway to the Montefeltro duchy) could also fall with ease into Federico’s hands, but, Montano went on, “the Duke of Urbino was a man so prudent that he would never try an enterprise whose outcome was not more than certain.” In a closed-door meeting with Montano, Riario then burst out: “Is it not amazing that we still have not managed to get rid of Lorenzo?” Montano replied: “Although many consider the Duke of Urbino Lorenzo’s enemy, he is not.” They debated the issue heartily, and finally Riario said: “I command that you, Cola, believe that the Duke of Urbino is an enemy of Lorenzo no less than I am! And if you don’t agree, it means that you are a no-good, born to be disobedient!”

No other written record of these exchanges exists, since Riario forbade that Montano write to him, even in code. In fact, when Cola was caught, he was found to possess sets of ciphers for use with the other major players, but not with Riario. Perhaps because he was trying to save his own life, Montano did not convert to Riario’s opinion that Federico was a committed enemy of Lorenzo. But in just a few months, Riario himself might have changed his mind about Federico’s ambivalent stance toward Lorenzo de’ Medici.