No man is an island entire unto himself.

John Donne

Communication can be treated as simple cause and effect. Isolate one interaction, treat it as a cause, and analyze the effect it has without considering further influences. We often talk as if this is what happens, but it is clearly a great simplification.

The laws of cause and effect work for inanimate objects; if one billiard ball collides with another, you can predict with a fair amount of accuracy the final resting place of each. After the initial collision they no longer influence each other.

Living systems are another matter. If I kick a dog, I could calculate the force and momentum of my foot and work out exactly how far the dog should travel in a particular direction, given its size and weight. The reality would be a bit different—if I were to be foolish enough to kick a dog, it might turn around and bite my leg. The dog's final resting place is very unlikely to be anything to do with Newton's laws of motion.

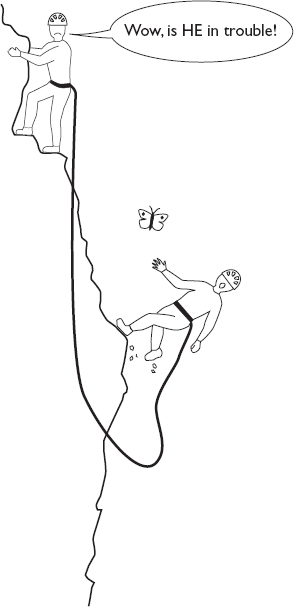

Human relationships are complex—many things happen simultaneously. You cannot predict exactly what will occur, because one person's response influences the other person's communication. The relationship is a loop; we are continuously responding to feedback in order to know what to do next. Focusing on only one side of the loop is like trying to understand tennis by studying only one end of the court. You could spend a lifetime figuring out how hitting the ball “causes” it to come back, and the laws that determine what the next shot must be. Our conscious mind is limited and can never see the whole loop of communication, only small parts of it.

The content and the context of a communication combine to make the meaning. The context is the total setting, the whole system that enfolds it. What does one piece of a jigsaw mean? Nothing in itself; it depends where it goes in the total picture, where it fits and what relationship it has to the other pieces.

What does a musical note mean? Very little on its own, it depends how it relates to the notes around it, how high or low it is, and how long it lasts. The same note can sound quite different if the notes around it change.

There are two main ways of understanding experience and events. You can focus on the content, information. What is this piece? What is it called? What does it look like? How is it like others? Most education is like this; jigsaw pieces can be interesting and beautiful to study in isolation, but you only get a one-dimensional understanding. Understanding in depth needs another viewpoint: relationship or context. What does the piece mean? How does it relate to others? Where does it fit into the system?

Our inner world of beliefs, thoughts, representational systems and submodalities also form a system. Changing one can have widespread effects and will generate other changes, as you will have discovered when you experimented with changing the submodalities of your experience.

A few well-chosen words at just the right time can transform a person's life. Changing one small piece of a memory can alter your whole state of mind. This is what happens when you deal with systems—one small push in the right direction can generate profound change, and you have to know where to push. Trying is useless. You can try really hard to feel better and finish feeling worse. Trying is like attempting to force a door inwards, you can waste a lot of energy before you realize it actually opens outward.

When we act to achieve our goals, we need to check that there are no inner reservations or doubts. We need also to pay attention to the outer ecology and appreciate the effect our goals will have on our wider system of relationships.

So the results of our actions come back to us in a loop. Communication is a relationship, not a one-way passage of information. You cannot be a teacher without a student, or a seller without a buyer, a counsellor without a client. Acting wholeheartedly with wisdom means appreciating the relationships and interactions between ourselves and others. The balance and relationship between parts of our mind will be a mirror of the balance and relationships we have with the outside world. NLP thinking is in terms of systems. For example, Gregory Bateson, one of the most influential figures in the development of NLP, applied cybernetic or systems thinking to biology, evolution and psychology, while Virginia Satir, the world-famous family therapist, and also one of the original models for NLP, treated a family as a balanced system of relationships, not a collection of individuals with problems to be fixed. Each person was a valuable part. She helped the family to achieve a better and healthier balance, and her art lay in knowing exactly where to intervene and exactly which person needed to change so that all the relationships improved. As with a kaleidoscope, you cannot change one piece without changing the whole pattern. But, which bit do you change to create the pattern you want? This is the art of effective therapy.

The best way to change others is to change yourself. Then you change your relationships and other people must change too. Sometimes we spend a lot of time on one level trying to change somebody, while on another level behaving in a way that exactly reinforces what they are doing. Richard Bandler calls this the “Go away . . . closer . . .” pattern.

There is a nice metaphor from physics known as the Butterfly Effect. In theory, the movement of a butterfly's wing can change the weather on the other side of the globe, for it might just disturb the air pressure at a critical time and place. In a complex system a small change can have a huge effect.

So not all elements in a system are equally important. Some can be changed with little effect, but others will have a widespread influence. If you want to induce changes in your pulse, appetite, life span, and growth rate, you need only tamper with a small gland called the pituitary at the base of your skull. It is the body's nearest equivalent to a master control panel. It works in the same way a thermostat controls a central heating system. You can set the radiators individually, but the thermostat controls them all. The thermostat is on a higher logical level than the radiators it controls.

NLP identifies and uses the successful elements that different psychologies have in common. The human brain has the same structure the world over, and has generated all the different psychological theories, so they are bound to share some basic patterns. Because NLP takes patterns across the whole field, it is on a different logical level. A book about how to make maps is on a different level to the various books of maps, even though it is another book.

We learn from our mistakes, much more than from our successes. They give us useful feedback, and we spend a lot more time thinking about them. We rarely get something right first time, unless it is very simple, and even then there will be room for improvement. We learn by a series of successive approximations. We do what we can (the present state) and compare that to what we want (desired state). We use this as feedback to act again and reduce the difference between what we want, and what we are getting. Slowly we approach our goal. This comparison drives our learning at every level through conscious incompetence to unconscious competence.

This is a general model of the way to become more effective at anything you do. You compare what you have with what you want, and act to reduce the mismatch. Then you compare again. The comparison will be based on your values: what is important to you in that situation. For example, in checking over these pages, I have to decide whether they are good enough or whether they need rewriting. My values are clarity of meaning (from the reader's viewpoint, not mine), correctness of grammar and the flow of the words.

I also need to decide on my evidence procedure. How will I know that it meets my values? If I have no evidence procedure I could go around and around the loop forever, because I will never know when to stop. This is a trap for authors who spend years correcting their manuscript to get it perfect and never publish at all. Evidence in my example would involve putting the text through the spell checker initially, then showing it to friends whose advice I value and getting their feedback. I would make alterations based on that feedback.

The model is known as the TOTE model, which stands for Test—Operate—Test—Exit. The comparison is the Test. The Operation is where you apply your resources. Test by comparing again and Exit from the loop when your evidence procedure tells you your outcome has been achieved. How successful you are will depend on the number of choices of operations you have: your flexibility of behavior, or requisite variety, a term from cybernetics. So the journey from present state to desired state is not even a zig-zag after all, but a spiral.

There will probably be smaller loops like this going on within the larger one: smaller outcomes that you need to achieve the main one. The whole system fits together like a collection of Chinese boxes. In this model of learning, mistakes are useful, for they are results you do not want in this context. They can be used as feedback to get closer to your goal.

Children are taught many subjects at school and forget most of them. They are not usually taught how to learn. Learning to learn is a higher-level skill than learning any particular material. NLP deals with how to become a better learner, regardless of the subject. The quickest and most effective way to learn is to use what happens naturally, and easily. Learning and change is often thought to be a slow, painful process. This is not true. There are slow and painful ways of learning and changing, but using NLP is not one of them.

Robert Dilts has developed a technique for converting what could be looked on as failure into feedback, and learning from it. It is easiest with another person taking you through the following steps.

As you think about the problem, what is your physiology and eye accessing position? Thinking about failure will usually involve a bad feeling, pictures of specific times you failed, and perhaps some internal voice reprimanding you, all at the same time. You cannot deal with them all together. You need to find out what is happening internally in each of the representational systems separately.

Look down left. Is there a message in the words taken in isolation that could be helpful?

Look up left and see the pictures of the memories. Is there something new you can learn from them? Start to get a more realistic perspective on the problem. You are capable of more than this. Notice how there are positive resources mixed in with the memories of the problem. Relate the words, pictures, and feelings to the desired goal. How can they help you achieve it?

Learning at the simplest level is trial and error with or without guidance. You learn to make the best choice available, the “right” answer. This may take one trial, or many trials. You learn to write, to spell, that red traffic lights mean stop. You start from unconscious incompetence and progress to conscious competence by going through the learning loop.

Once a response becomes a habit, you stop learning. Theoretically, you could act differently, but in practice you do not. Habits are extremely useful, they streamline the parts of our lives we do not want to think about. How tedious to decide how to do up your shoelaces every morning. Definitely not an area to engage your creativity. But there is an art to deciding what parts of your life you want to turn over to habit, and what parts of your life you want to continue to learn from and have choice about. This is a key question of balance.

This question actually takes you up a level. You can look at the skills you have learned, and choose between them, or create new choices that will fulfil the same intention. Now you can learn to be a better learner, by choosing how you are going to learn.

The poor man who was granted three wishes in the fairy story obviously did not know about levels of learning. If he had known, instead of using his last wish to restore the status quo, he would have wished for three more wishes.

Children learn at school that 4 + 4 = 8. At one level this is simple learning. You do not need to understand, just remember. There is an automatic association; it has been anchored. Left at this level, this would mean that 3 + 5 cannot make 8 because 4 + 4 do. Obviously learning mathematics this way is useless. Unless you connect your ideas to a higher level, they remain limited to a particular context. True learning involves learning other ways of doing what you can do already. You learn that 1 and 7 make 8 and so do 2 and 6. Then you can go up a level and understand the rules behind these answers. Knowing what you want, you can find different creative ways of satisfying it. Some people will change what they want rather than what they are doing to get it. They give up trying to get 8 because they are determined to use 3 + 4, and it will not work out. Others may always use 4 + 4 to make 8, never anything else.

The so-called “hidden curriculum” of schools is an example of higher-level learning. Regardless of what is learned, how is it learned? Nobody consciously teaches the values of the hidden curriculum it is the school as a context, and has a greater influence on children's behavior than the formal lessons. If children never learn that there are any other ways to learn than passively, by repetition, in a peer group, and from someone in authority, they are in an analogous position at a higher level to the child who learns that 4 + 4 is the only way to make 8.

A still higher level of learning results in a profound change in the way we think about ourselves and the world. It involves understanding the relationships and paradoxes of the different ways we learn to learn.

Gregory Bateson tells an interesting story in his book Steps to the Ecology of Mind about the time he was involved in studying the communication patterns of dolphins at the Marine Research Institute in Hawaii. He would watch the trainers teach the dolphins to do tricks for a paying audience. On the first day, when the dolphin did something unusual, such as jumping out from the water, the trainer blew a whistle and threw the dolphin a fish as a reward. Every time the dolphin behaved that way, the trainer would blow the whistle and throw the dolphin a fish. Very soon the dolphin learned that this behavior guaranteed a fish; it would repeat it more and more and come to expect the reward.

The next day the dolphin would come out and do its jump, expecting a fish, but none was forthcoming. The dolphin would repeat its jump fruitlessly for some time, then in annoyance do something else such as rolling over. The trainer then blew the whistle and threw the dolphin a fish. The dolphin then repeated this new trick, and was rewarded with fish. No fish for yesterday's trick, only for something new. This pattern was repeated for 14 days. The dolphin would come out and do the trick it had learned the day before for some time to no avail. When it did something new, it was rewarded. This was probably very frustrating for the dolphin. On the fifteenth day however, it suddenly appeared to learn the rules of the game. It went wild and put on an amazing show, including eight new unusual behaviors, four of which had never been observed in the species before. The dolphin had moved up a learning level. It seemed to understand not only how to generate new behaviors, but the rules about how and when to generate them.

One further point: during the 14 days Bateson saw the trainer throwing unearned fish for the dolphin outside the training context. When he questioned this, the trainer replied, “That is to keep my relationship with him. If I do not have a good relationship, he is not going to bother about learning anything”.

To learn the most from any situation or experience, you will need to gather information from as many points of view as possible. Each representational system gives a different way of describing reality. New ideas emerge from these different descriptions as white light emerges when you combine the colors of the rainbow. You cannot function with just one representational system. You need at least two: one to take in the information, and another to interpret it in a different way.

In the same way any single person's viewpoint will have blind spots caused by their their habitual ways of perceiving the world, their perceptual filters. By developing the skill of seeing the world from other people's points of view we have a way of seeing through our own blind spots, in the way that we ask a friend for advice and a different viewpoint if we are stuck. How can we shift our perceptions to get outside our own limited world view?

There is a minimum of three ways we can look at our experience. In the most recent work by John Grinder and Judith DeLozier they are called first, second, and third perceptual positions. Firstly, you can look at the world completely from your own point of view, your own reality within yourself, in a completely associated way, and not take anyone else's point of view into account. You simply think, “How does this affect me?” Think back and concentrate on a time when you were intensely aware of what you thought, regardless of anyone else in the situation. This is called “first position” (and you have just experienced it as you concentrated on your own reality, regardless of the instance you selected).

Secondly, you can consider how it would look, feel, and sound from another person's point of view. It is obvious that the same situation or behavior can mean different things to different people, so it is essential to appreciate another person's point of view and ask, “How would this appear to them?” This is called “second position”, often known as empathy. If you are in conflict with another person, you need to appreciate how they feel about what you are doing. The stronger the rapport you have with the other person, the better you will be able to appreciate their reality, and the more skilled you will be at achieving second position.

Thirdly, you can have the experience of seeing the world from an outside point of view, as if you are a completely independent observer, someone with no personal involvement in the situation. Ask, “How would this look to someone who is not involved?” This gives you an objective viewpoint and is known as “third position”. It is on a different level to the other two, but it is not superior. Third position is different from being dissociated. For third position to be useful you need to be in a strong, resourceful state. You take an objective and resourceful view of your own behavior so you can evaluate and generate some useful choices in any difficult situation. Being able to take a third position view of a problem is a very useful skill and can save you a lot of the stress and trouble that results from hasty actions. All three positions are equally important; the point is to be able to move between them freely. Someone stuck in first position will be an egoistical monster, while someone habitually in second will be unduly influenced by other people's views. Someone habitually in third will be a detached observer of life.

The idea of triple description is just one aspect of the approach taken by John Grinder and Judith DeLozier in their book Turtles All the Way Down to describe NLP in a simpler way. The approach is known as the “new code” of NLP, and focuses on achieving a wise balance between conscious and unconscious processes.

We all spend time in these three positions, we do them naturally, and they help us to understand any situation or outcome better. The ability to move cleanly between them, consciously or unconsciously, is necessary to act with wisdom, and to appreciate the wonderful complexity of our relationships. The differences you see when you look at the world in different ways are what give it richness and what gives you choice. First, second, and third positions are an explicit recognition that the map is not the territory. There are many different maps.

The idea is to be aware of difference, rather than try to impose uniformity. It is the difference and the tension between these different ways of looking at the world that is important. Excitement and invention comes from seeing things in a different way. Sameness breeds boredom, mediocrity and struggle. In biological evolution it is the species that are the same that come into conflict and struggle to survive. Wars erupt when people want exactly the same scarce resources. Wisdom comes from balance, and you cannot balance unless there are different forces to be balanced.

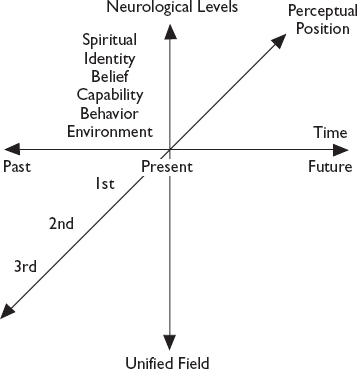

Robert Dilts has built a simple, elegant model for thinking about personal change, learning and communication that brings together these ideas of context, relationship, levels of learning, and perceptual position. It also forms a context for thinking about the techniques of NLP, and gives a framework for organizing and gathering information, so you can identify the best point to intervene to make the desired change. We do not change in bits and pieces, but organically. The question is, exactly where does the butterfly have to move its wings? Where to push to make a difference?

Learning and change can take place at different levels.

1. Spiritual

This is the deepest level, where we consider and act out the great metaphysical questions. Why are we here? What is our purpose? The spiritual level guides and shapes our lives, and underpins our existence. Any change at this level has profound repercussions on all other levels, as St Paul found on the road to Damascus. In one sense it contains everything we are and do, and yet is none of those things.

2. Identity

This is my basic sense of self, my core values, and mission in life.

3. Beliefs

The various ideas we think are true, and use as a basis for daily action. Beliefs can be both permissions and limitations.

4. Capability

These are the groups or sets of behaviors, general skills, and strategies that we use in our life.

5. Behavior

The specific actions we carry out, regardless of our capability.

6. Environment

What we react to, our surroundings and the other people we meet.

To take an example of a salesman thinking about his work at these different levels:

Environment: This neighborhood is a good area for my work in selling.

Behavior: I made that sale today.

Capability: I can sell this product to people.

Belief: If I do well at sales, I could be promoted.

Identity: I am a good salesman.

Neurological Levels

This is an example of success. The model can equally well be applied to problems. For example, I might misspell a word. I could put this down to the environment: the noise distracted me. I could leave it at the level of behavior. I got this one word wrong. I could generalize and question my capability with words. I could start to believe I need to do more work to improve, or I could call my identity into question by thinking I am stupid.

Behavior is often taken as evidence of identity or capability, and this is how confidence and competence are destroyed in the classroom. Getting a sum wrong does not mean you are stupid or that you are poor at math. To think this is to confuse logical levels, equivalent to thinking a “No Smoking” sign in a cinema applies to the characters in the film.

When you want to change yourself or others, you need to gather information, the noticeable parts of the problem, the symptoms that the person is uncomfortable with. This is the present state. Less obvious than the symptoms are the underlying causes that maintain the problem. What does the person have to keep doing to maintain the problem?

There will be a desired state, an outcome which is the goal of change. There will be the resources that will help to achieve this outcome. There are also side effects of reaching the outcome, both for oneself and others.

From this model it is possible to see how you can be embroiled in two types of conflict. You might have difficulty choosing between staying in and watching television and going out to the theater. This is a straightforward clash of behaviors.

There could be a clash where something becomes good on one level but bad on another. For example, a child may be very good at drama in school, but believe that doing it will make him unpopular with his classmates, so he does not do it. Behaviors and capabilities may be highly rewarded, yet clash with one's beliefs or identity.

The way we view time is important. A problem may have to do with a past trauma, which has continuing repercussions in the present. A phobia would be an example, but there are many others, less dramatic, where difficult and unhappy times in the past affect our quality of life in the present. Many therapies think of present problems as determined by past events. While we are influenced by, and create our personal history, the past can be used as a resource rather than as a limitation. The Change Personal History technique has already been described. It re-evaluates the past in terms of present knowledge. We are not trapped forever to repeat past mistakes.

On the other hand, hopes and fears for the future can paralyse you in the present. This can range from worrying about giving an after dinner speech on Wednesday week, to important questions of personal and financial security in the future. And there is the present moment when all our personal history and possible futures converge. You can imagine your life on a line through time, stretching from distant past to distant future, and see how the present and desired state, identity, belief, capability, behavior, and environment all relate to your personal history and possible future.

Our total personality is like a hologram, a three-dimensional image created by beams of light. Any piece of the hologram will give you the whole image. You can change small elements like submodalities and watch the effect ripple upward, or work from the top downwards by changing an important belief. The best way will become apparent as you gather information about the present and desired states.

Change on a lower level will not necessarily cause any change on higher levels. A change in environment is unlikely to change my beliefs. How I behave may change some beliefs about myself. However change in belief will definitely change how I behave. Change at a high level will always affect the lower levels. It will be more pervasive and lasting.

So if you want to change behavior, work with capability or belief. If there is a lack of capability, work with beliefs. Beliefs select capabilities which select behaviors, which in turn directly build our environment. A supportive environment is important, a hostile environment can make any change difficult.

It is difficult to make a change at the level of identity or beyond without the beliefs and capabilities to support you. Nor is it enough for a businessman to believe he can be a top manager—he needs to back his belief up with work. Beliefs without capabilities and behaviors to back them up are castles built on sand.

The unified field is a way of putting together the different parts of NLP in a framework made up from the ideas of neurological levels, time and perceptual position. You can use it to understand the balance and relationship of the different elements in yourself and others. The key is balance. Problems arise from a lack of balance, and the unified field enables you to identify which elements have assumed too great an importance, and which are absent or too weak.

For example, a person may put too much emphasis on past time and pay undue attention to past events, letting these influence her life, and devalue the present and the future. Another person might spend too much time in first position, and not take other people's viewpoints into account. Others may pay a lot of attention to behavior and environment, and not enough to their identity and beliefs. The unified field framework gives you a way of identifying an imbalance, as a necessary first step to finding ways of achieving a healthier balance. For therapists it is invaluable as a diagnostic tool to let you know which of the many techniques to use. This is a rich model and we leave you to think of the many different ways you can use it. into account. Others may pay a lot of attention to behaviour and environment, and not enough to their identity and beliefs. The unified field framework gives you a way of identifying an imbalance, as a necessary first step to finding ways of achieving a healthier balance. For therapists it is invaluable as a diagnostic tool to let you know which of the many techniques to use. This is a rich model and we leave you to think of the many different ways you can use it.

“I can't believe that!” said Alice.

“Can't you?”. the Queen said in a pitying tone. “Try again: draw a long breath, and shut your eyes”.

Alice laughed. “There's no use trying”, she said. “One can't believe impossible things”.

“I dare say you haven't had much practice”, said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I've believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast”.

Alice Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll

Our beliefs strongly influence our behavior. They motivate us and shape what we do. It is difficult to learn anything without believing it will be pleasant and to our advantage. What are beliefs? How are they formed, and how do we maintain them?

Beliefs are our guiding principles, the inner maps we use to make sense of the world. They give stability and continuity. Shared beliefs give a deeper sense of rapport and community than shared work.

We all share some basic beliefs that the physical world confirms every day. We believe in the laws of nature. We do not walk off the tops of buildings, or need to test anew each day that fire burns. We also have many beliefs about ourselves and the sort of world we live in that are not so clearly defined. People are not so consistent and immutable as the force of gravity.

Beliefs come from many sources—upbringing, modeling of significant others, past traumas, and repetitive experiences. We build beliefs by generalizing from our experience of the world and other people. How do we know what experiences to generalize from? Some beliefs come to us ready made from the culture and environment we are born into. The expectations of the significant people around us in childhood instil beliefs. High expectations (providing they are realistic) build competence. Low expectations instil incompetence. We believe what we are told about ourselves when we are young because we have no way of testing, and these beliefs may persist unmodified by our later achievements.

When we believe something, we act as if it is true. This makes it difficult to disprove; beliefs act as strong perceptual filters. Events are interpreted in terms of the belief, and exceptions prove the rule. What we do maintains and reinforces what we believe. Beliefs are not just maps of what has happened, but blueprints for future actions.

Studies have been done where a group of children have been divided into two groups of equal IQ. Teachers were told that one group had a high IQ and were expected to do better than the second group. Although the only difference between the two groups was the teachers' expectation (a belief), the “high IQ” group got much better results than the second group when tested later. This type of selffulfilling prophecy is sometimes known as the Pygmalion effect.

A similar kind of self-fulfilling prophecy is the placebo effect, well known in medicine. Patients will improve if they believe they are being given an effective drug, even when they are actually being given placebos, inert substances with no proven medical effect. The belief effects the cure. Drugs are not always necessary, but belief in recovery always is. Studies consistently show that about 30 percent of patients respond to placebos.

In one study a doctor gave an injection of distilled water to a number of patients with bleeding peptic ulcers, telling them that it was a wonder drug and it would cure them. Seventy percent of the patients showed excellent results which lasted over a year.

Positive beliefs are permissions that turn on our capabilities. Beliefs create results. There is a saying, “Whether you believe you can or you can't do something . . . You're right”.

Limiting beliefs usually centre around, “I can't . . .” Regard this phrase as simply a statement of fact that is valid for the present moment only. For example, to say, “I can't juggle” means I can (not juggle). It is very easy not to juggle. Anyone can do it. Believing that “I can't” is a description of your capability now and in the future, instead of being a description of your behavior now, will program your brain to fail, and this will prevent you finding out your true capability. Negative beliefs have no basis in experience.

A good metaphor for the effect of limiting beliefs is the way a frog's eye works. A frog will see most things in its immediate environment, but it only interprets things that move and have a particular shape and configuration as food. This is a very efficient way of providing the frog with food such as flies. However, because only moving black objects are recognized as food, a frog will starve to death in a box of dead flies. So perceptual filters that are too narrow and too efficient can starve us of good experiences, even when we are surrounded by exciting possibilities, because they are not recognized as such.

The best way to find out what you are capable of is to pretend you can do it. Act “as if” you can. What you can't do, you won't. If it really is impossible, don't worry, you'll find that out. (And be sure to set up appropriate safety measures if necessary.) As long as you believe it is impossible, you will actually never find out if it is possible or not.

We are not born with beliefs as we are with eye color. They change and develop. We think of ourselves differently, we marry, divorce, change friendships, and act differently because our beliefs change.

Beliefs can be a matter of choice. You can drop beliefs that limit you and build beliefs that will make your life more fun and more successful. Positive beliefs allow you to find out what could be true and how capable you are. They are permissions to explore and play in the world of possibility. What beliefs are worth having that will enable and support you in your goals? Think of some of the beliefs you have about yourself. Are they useful? Are they permissions or barriers? We all have core beliefs about love, and what is important in life. We have many others about our possibilities and happiness that we have created, and can change. An essential part of being successful is having beliefs that allow you to be successful. Empowering beliefs will not guarantee you success every time, but they keep you resourceful and capable of succeeding in the end.

There have been some studies at Stanford University on “Self Efficacy Expectation”, or how behavior changes to match a new belief. The study was about how well people think they do something, compared to how well they actually do it. A variety of tasks were used, from mathematics to snake handling.

At first, beliefs and performance matched, people performed as they thought they would. Then the researchers set about building the subjects' belief in themselves by setting goals, arranging demonstrations, and giving them expert coaching. Expectations rose, but performance typically dropped because they were trying out new techniques. There was a point of maximum difference between what they believed they could do, and what they were actually achieving. If the subjects stuck to the task, their performance would rise to meet their expectations. If they became discouraged, it dropped to its initial level.

Think for a moment of three beliefs that have limited you. Go ahead and write them down.

Now, in your mind, look into a huge, ugly mirror. Imagine how your life will be in five years if you continue to act as if these limiting beliefs were true. How will your life be in ten years? In twenty?

Take a moment to clear your mind. Stand up, walk around, or take a few deep breaths. Now think of three new beliefs that would empower you, that would truly enhance the quality of your life. You can stop for a few seconds to write these down now.

In your mind, look into a big, friendly mirror. Imagine yourself acting as if these new beliefs were really true. How will your life be in five years now? In ten years? In twenty?

Changing beliefs allows behavior, to change, and it changes quickest if you are given a capability or strategy to accomplish the task. You can also change a person's belief through changing their behavior, but this is not so reliable. Some people are never convinced by repeated experiences. They see only disconnected coincidences.

Beliefs are an important part of our personality, yet they are expressed in extraordinarily simple terms: if I do this . . . then that will happen. I can . . . I can't . . . And these are translated into: I must . . . I should . . . I must not . . . The words become compelling. How do these words gain their power over us? Language is an essential part of the process we use to understand the world and express our beliefs. In the next chapter we take a closer look at the linguistic part of Neuro-Linguistic Programming.