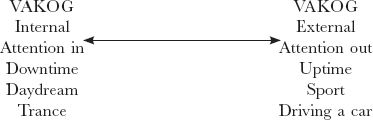

So far we have concentrated on the importance of sensory acuity, keeping the senses open and noticing the responses of people around you. This state of tuning the senses to the outside world is known as Uptime in NLP terms. However, there are also states that take us deeper into our own mind, our own reality.

Break off from this book for a moment and remember a time when you were deep in thought . . .

You probably had to go deep in thought to remember. You would have focused inwards, feeling, seeing, and hearing inwardly. This is a state we are all familiar with. The more deeply you go in, the less you are aware of outside stimuli; deep in thought is a good description of this state, known as Downtime in NLP. Accessing cues take you into downtime. Whenever you ask anyone to go inside to visualize, hear sounds and have feelings, you are asking him to go into downtime. Downtime is where you go to daydream, to plan, to fantasize, and create possibilities.

In practice we are seldom completely in uptime or downtime; our everyday consciousness is a mixture of partly internal and partly external awareness. We turn the senses outward or inwards depending on the circumstances we are in.

It is useful to think of mental states as tools for doing different things. Playing a game of chess involves a radically different state of mind to eating. There is no such thing as a wrong state of mind, but there are consequences. These could be catastrophic, if, for example, you try to cross a busy street in the state of mind you use to go to sleep—uptime is most definitely the best state to use for crossing the road—or laughable, if you try to say a tongue twister while in the state of mind brought on by too much alcohol. Often you do not do something well because you are not in the right state. You will not play a good game of tennis if you are in the state of mind you use to play chess.

You can access unconscious resources directly by inducing and using a type of downtime known as trance. In trance you become deeply involved in a limited focus of attention. It is an altered state from your habitual state of consciousness. Everybody's experience of trance will be different, because everybody starts from a different normal state, dominated by their preferred representational systems.

Most of the work on trance and altered states has been done in a psychotherapy setting, for all therapies use trance to some extent. They all access unconscious resources in different ways. Anyone freeassociating on an analyst's couch is well into downtime, and so is someone who is role playing in Gestalt therapy. Hypnotherapy uses trance explicitly.

A person goes into therapy because he has run out of conscious resources. He is stuck. He does not know what he needs or where to find it. Trance offers an opportunity to resolve the problem because it bypasses the conscious mind and makes unconscious resources available. Most change takes place at the unconscious level and work their way up. The conscious mind is not needed to initiate changes and often does not notice them anyway. The ultimate goal of any therapy is for the client to become resourceful again in his or her own right. Everyone has a rich personal history, filled with experience and resources that can be drawn on. It contains all the material needed to make changes, if only you can get at it.

One of the reasons that we use such a small part of our possible mental capacity could be that our education system places so much emphasis on external testing, standardized achievements and meeting other people's goals. We get little training in utilizing our unique internal abilities. Most of our individuality is unconscious. Trance is the ideal state of mind to explore and recover our unique internal resources.

“That's a great deal to make one word mean”, Alice said in a thoughtful tone.

“When I make a word do a lot of work like that”, said Humpty Dumpty, “I always pay it extra”.

Alice Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll

Gregory Bateson was enthusiastic about The Structure of Magic I, which contained the Meta Model. He saw great potential in the ideas. He told John and Richard, “There's a strange old guy down in Phoenix, Arizona. A brilliant therapist, but nobody knows what he's doing, or how he does it. Why don't you go and find out?” Bateson had known this “strange old guy”, Milton Erickson, for 15 years, and he set up an appointment for them to meet Erickson.

John and Richard worked with Milton Erickson in 1974 when he was widely regarded as the foremost practitioner of hypnotherapy. He was the founding president of the American Society for Clinical Hypnosis, and travelled extensively giving seminars and lectures as well as working in private practice. He had a world-wide reputation as a sensitive and successful therapist, and was famous for his acute observation of nonverbal behavior. John and Richard's study gave rise to two books. Patterns of Hypnotic Techniques of Milton H. Erickson Volume I was published by Meta Publications in 1975. Volume 2, cowritten with Judith DeLozier, followed in 1977. The books are as much about their perceptual filters as Erickson's methods, although Erickson did say that the books were a far better explanation of his work than he himself could have given. And that was a fine compliment.

John Grinder has said that Erickson was the single most important model that he ever built, because Erickson opened the doorway not just to a different reality, but to a whole different class of realities. His work with trance and altered states was astonishing, and John's thinking underwent a profound rebalancing.

NLP underwent a rebalancing too. The Meta Model was about precise meanings. Erickson used language in artfully vague ways so that his clients could take the meaning that was most appropriate for them. He induced and utilized trance states, enabling individuals to overcome problems and discover their resources. This way of using language became known as the Milton Model, as a complement and contrast to the exactness of the Meta Model.

The Milton Model is a way of using language to induce and maintain trance in order to contact the hidden resources of our personality. It follows the way the mind works naturally. Trance is a state where you are highly motivated to learn from your unconscious in an inner directed way. It is not a passive state, nor are you under another's influence. There is co-operation between client and therapist, the client's responses letting the therapist know what to do next.

Erickson's work was based on a number of ideas shared by many sensitive and successful therapists. These are now presuppositions of NLP. He respected the client's unconscious mind. He assumed there was a positive intention behind even the most bizarre behavior, and that individuals make the best choices available to them at the time. He worked to give them more choices. He also assumed that at some level, individuals already have all the resources they need to make changes.

The Milton Model is a way of using language to:

Milton Erickson was masterful at gaining rapport. He respected and accepted his clients' reality. He assumed that resistance was due to lack of rapport. To him, all responses were valid and could be used. To Erickson, there were no resistant clients, only inflexible therapists.

To pace someone's reality, to tune into their world, all you need do is to simply describe their ongoing sensory experience: what they must be feeling, hearing and seeing. It will be easy and natural for them to follow what you are saying. How you talk is important. You will best induce a peaceful inward state by speaking slowly, using a soft tonality and pacing your speech to the person's breathing.

Gradually suggestions are introduced to lead them gracefully into downtime by directing their attention inwards. Everything is described in general terms so it accurately reflects the person's experience. You would not say, “Now you will close your eyes and feel comfortable and go into a trance”. Instead you might say, “It's easy to close your eyes whenever you wish to feel more comfortable . . . many people find it easy and comfortable to go into a trance”. These sort of general comments cover any response, while gently introducing the trance behavior.

A loop is set up. As the client's attention is constantly focused and riveted on a few stimuli, he goes deeper into downtime. His experiences become more subjective, and these are fed back by the therapist to deepen the trance. You do not tell a person what to do, you draw his attention to what is there. How can you possibly know what a person is thinking? You cannot. There is an art to using language in ways that are vague enough for the client to make an appropriate meaning. It is a case not so much of telling him what to think, but of not distracting him from the trance state.

These sort of suggestions will be most effective if the transitions between sentences are smooth. For example, you might say something like, “As you see the colored wallpaper in front of you . . . the patterns of light on the walls . . . while you become aware of your breathing . . . the rise and fall of your chest . . . the comfort of the chair . . . the weight of your feet on the floor . . . and you can hear the sounds of, the children playing outside . . . while you listen to the sound of my voice and begin to wonder . . . how far you have entered trance . . . already”.

Notice the words “and”, “while” and “as” in the example as they smoothly link the flow of suggestions, while you mention something that is occurring (the sound of your voice) and link it to something that you want to occur (going into trance).

Not using transitions makes jumpy sentences. They will be detached from each other. Then they are less effective. I hope this is clear. Writing is like speech. Smooth or staccato. Which do you prefer?

A person in a trance is usually still, the eyes are usually closed, the pulse is slower and the face relaxed. The blinking and swallowing reflexes are normally slower or absent, and the breathing rate is slower. There is a feeling of comfort and relaxation. The therapist will either use a prearranged signal to bring the client out of trance, or lead them out by what he says, or the person may spontaneously return to normal consciousness if his unconscious thinks this is appropriate.

The Meta Model keeps you in uptime. You do not have to go inside your mind searching for the meaning of what you hear; you ask the speaker to spell it out specifically. The Meta Model recovers information that has been deleted, distorted, or generalized. The Milton Model is the mirror image of the Meta Model; it is a way of constructing sentences rife with deletions, distortions and generalizations. The listener must fill in the details and actively search for the meaning of what he hears from his own experience. In other words you provide context with as little content as possible. You give him the frame and leave him to choose the picture to put in it. When the listener provides the content, this ensures he makes the most relevant and immediate meaning from what you say.

Imagine being told that in the past you have had an important experience. You are not told what it was, you must search back through time and select an experience that seems most relevant to you now. This is done at an unconscious level, our conscious mind is much too slow for the task.

So a sentence like, “People can make learnings”, is going to evoke ideas about what specific learnings I can make, and if I am working on a particular problem those learnings are bound to relate to questions I am pondering. We make this kind of search all the time to make sense of what others tell us, and it is utilized to the full in trance. All that matters is the meaning that the client makes; the therapist need not know.

It is easy to make up artfully vague instructions so that a person can pick an appropriate experience and learn from it. Ask him to pick some important experience in his past, and go through it again in all internal senses to learn something new from it. Then ask his unconscious to use this learning in future contexts where it could be useful.

An important part of the Milton Model is leaving out information, and so keeping the conscious mind busy filling the gaps from its store of memories. Have you ever had the experience of reading a vague question and trying to work out what it could mean?

Nominalizations delete a great deal of information. As you sit with a feeling of ease and comfort, your understanding of the potential of this sort of language is growing, for every nominalization in this sentence is in italics. The less that is mentioned specifically, the less risk of a clash with the other person's experience.

Verbs are left unspecified. As you think of the last time you heard someone communicate using unspecified verbs, you might remember the feeling of confusion you experienced, and how you have to search for your own meaning to make sense of this sentence.

In the same way noun phrases can be generalized or left out completely. It is well known that people can read books and make changes. (Well known by whom? Which people, what books, and how will they make these changes? And what will they change from, and what will they change to?)

Judgments can be used. “It is really good to see how relaxed you are”.

Comparisons also have deletions. “It is better to go into a deeper trance”.

Both comparisons and judgments are good ways of delivering presuppositions. These are powerful ways of inducing and utilizing trance. You presuppose what you do not want questioned. For example:

“You may wonder when you will go into a trance”. Or, “Would you like to enter trance now or later?” (You will go into a trance, the only question is when.)

“I wonder if you realize how relaxed you are?” (You are relaxed.)

“When your hand rises that will be the signal you have been waiting for”. (Your hand will rise and you are waiting for a signal.)

“You can relax while your unconscious learns”. (Your unconscious is learning.)

“Can you enjoy relaxing and not having to remember?” (You are relaxed and will not remember.)

Transitions (and, as, when, during, while) to link statements are a mild form of cause and effect. A stronger form is to use the word “make”, e.g. “Looking at that picture will make you go into a trance”.

I am sure you are curious to know how mind reading can be woven into this model of using language. It must not be too specific, or it may not fit. General statements about what the person may be thinking act to pace and then lead their experience. For example, “You might wonder what trance will be like”, or, “You are beginning to wonder about some of the things I am saying to you”.

Universal quantifiers are used too. Examples are: “You can learn from every situation”, and, “Don't you realize the unconscious always has a purpose?”

Modal operators of possibility are also useful. “You can't understand how looking at that light puts you deeper into trance”. This also presupposes that looking at the light does deepen the trance. “You can't open your eyes”, would be too direct a suggestion, and invites the person to disprove the statement. “You can relax easily in that chair”, is a different example. To say you can do something gives permission without forcing any action. Typically people will respond to the suggestion by doing the permitted behavior. At the very least, they will have to think about it.

How does the brain process language and how does it deal with these artfully vague forms of language? The front part of the brain, the cerebrum, is divided into two halves or hemispheres. Information passes between them through the connecting tissue, the corpus callosum.

Experiments which measured the activity in both hemispheres for different tasks have shown they have different but complementary functions. The left hemisphere is commonly known as the dominant hemisphere and deals with language. It processes information in an analytical, rational way. The right side, known as the nondominant hemisphere, deals with information in a more holistic and intuitive way. It also seems to be more involved in melody, visualization, and tasks involving comparison and gradual change.

This specialization of the hemispheres holds true for over 90 percent of the population. For a small minority (usually left-handed people) it is reversed and the right hemisphere deals with language. Some people have these functions scattered over both hemispheres.

There is evidence that the nondominant hemisphere also has language abilities, mostly simple meanings and childish grammar. The dominant hemisphere has been identified with the conscious mind, and the nondominant with the unconscious, but this is too simple. It is useful to think of our left brain dealing with our conscious understanding of language and the right brain dealing with simple meanings, in an innocent way below our level of awareness.

Milton Model patterns distract the conscious mind by keeping the dominant hemisphere overloaded. Milton Erickson could speak in such a complex and multilayered way that all the seven plus or minus two chunks of conscious attention were engaged searching for possible meanings and sorting out ambiguities. There are many ways of using language to confuse and distract the left hemisphere.

Ambiguity is one such method. What you say can be soundly ambiguous. Like the last sentence. Does “soundly” here mean definitely or phonetically? Hear, it means the latter, and it's a good example of one word carrying two meanings. Another example would be, “When you experience insecurity . . . (In security?)”

There are many words that have different meanings but sound the same . . . there/they're . . . nose/knows. It is difficult to right/write phonological ambiguity.

Another form of ambiguity is called syntactic, for example, “Fascinating people can be difficult”. Does this mean the people are fascinating, or is it difficult to fascinate people? This sort of ambiguity is constructed by using a verb plus “ing” and making a sentence where it is not clear whether it serves as an adjective or a verb.

A third type is called punctuation ambiguity. As you read this sentence is an example of punctuation ambiguity. Two sentences run together that begin and end with the same word(s). I hope you can hear you are reading this book. All these forms of language take some time to sort out and they fully engage the left hemisphere.

The right hemisphere is sensitive to voice tone, volume, and direction of sound: all those aspects that can change gradually rather than the actual words which are separate from each other. It is sensitive to the context of the message, rather than the verbal content. As the right hemisphere is capable of understanding simple language forms, simple messages that are given some special emphasis will go to the right brain. Such messages will bypass the left brain, and will seldom be consciously recognized.

There are many ways to give this sort of emphasis. You can mark out portions of what you say with different voice tones or gestures. This can be used to mark out instructions or questions for unconscious attention. In books this is done by using italics. When an author wishes to please you and wants you to read something on this page, a particular sentence, very carefully, he will mark it out in italics.

Did you get the message embedded in it?

In the same way words can be marked out in a particular voice tone for special attention to form a command that is embedded in the speech. Erickson, who was confined to a wheelchair for part of his life, was adept at moving his head to make parts of what he said come from different directions. For example, “Remember you don't have to close your eyes to go into a trance”. He would mark out the embedded command by moving his head when he said those words in italics. Marking out important words with voice and gesture is an extension of what we do naturally all the time in normal conversation.

There is a good analogy with music. Musicians mark out important notes in the flow of the music in various ways to make a tune. The listener may not notice this consciously if the notes are far apart and the intervening material is diverting, but it all adds to his pleasure and appreciation. He does not need to be aware of the performer's device.

You can embed questions in longer sentences in the same way. “I wonder if you know which of your hands is warmer than the other?” This also contains a presupposition. It is not a direct question, but it will typically result in the person checking his hands for warmth. I wonder if you fully appreciate what a gentle and elegant way to gather information this pattern is?

There is an interesting pattern known as quotes. You can say anything if you first set up a context where it is not really you saying it. The easiest way to do this is by telling a story where someone says the message you want to convey, and mark it out in some way from the rest of the story.

I am reminded of a time when we did a seminar on these patterns. One of the participants came up to us afterward, and we asked him during the course of the conversation if he had heard of the quotes pattern. He said, “Yes. It was funny how that happened. I was walking down a street a couple of weeks ago and a complete stranger came up to me and said, 'Isn't this quotes pattern interesting?”

Negatives fit into these patterns. Negatives exist only in language, not experience. Negative commands work just like positive commands. The unconscious mind does not process the linguistic negative and simply disregards it. A parent or teacher who tells a child not to do something is ensuring the child will do it again. Tell a tightrope walker, “Be careful!” not “Don't slip!”

What you resist persists because it still has your attention. This being so, we would not want you to consider how much better and more effective your communication would be if it were phrased positively . . .

The last pattern we will deal with here is called conversational postulates.

These are questions that literally only require a yes/no answer, yet actually draw a response. For example, “Can you take out the garbage?” is not a literal request about your physical capability to do this task, but a request to do so. Other examples are:

“Is the door still open?” (Shut the door.)

“Is the table set?” (Set the table.)

These patterns are used all the time in normal conversation and we all respond to them. If you know about them, you can be more selective where you use them, and have more choice about whether you react to them. Because these patterns are so common, John Grinder and Richard Bandler would contradict each other in public seminars. One would say, “There is no such thing as hypnosis”, the other, “No! everything is hypnosis”. If hypnosis is just another word for multilayered, influential communication, it may be that we are all hypnotists and we are constantly moving in and out of trance . . . now . . .

The word metaphor is used in NLP in a general way to cover any story or figure of speech implying a comparison. It includes simple comparisons or similes, and longer stories, allegories, and parables. Metaphors communicate indirectly. Simple metaphors make simple comparisons: as white as a sheet, as pretty as a picture, as thick as two short planks. Many of these sayings become cliches, but a good simple metaphor can illuminate the unknown by relating it to what you already know.

Complex metaphors are stories with many levels of meaning. Telling a story elegantly distracts the conscious mind and activates an unconscious search for meaning and resources. As such, it is an excellent way of communicating with someone in a trance. Erickson made extensive use of metaphors with his clients.

The unconscious appreciates relationships. Dreams make use of imagery and metaphor; one thing stands for another because they have some feature in common. To create a successful metaphor, one that will point the way toward resolving a problem, the relationships between the elements of the story need to be the same as the relationships between the elements of the problem. Then the metaphor will resonate in the unconscious and mobilize the resources there. The unconscious gets the message and starts to make the necessary changes.

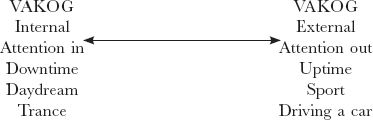

Creating a metaphor is like composing music, and metaphors affect us in the same way music does. A tune consists of notes in a relationship, it can be transposed higher or lower and will still be the same tune, provided the notes still have the same relationships to each other, the same distances between them, as they had in the original tune. At a deeper level, these notes combine to make chords, and a sequence of chords will have certain relationships to each other. Musical rhythm is how long different notes last relative to each other. Music is meaningful in a different way to language. It goes straight to the unconscious; the left brain has nothing to catch on to.

Creating a metaphor is like composing music.

Like good music, good stories must create expectation and then satisfy it in some way consistent with the style of the composition. The “with a bound he was free” type of solutions are not allowed.

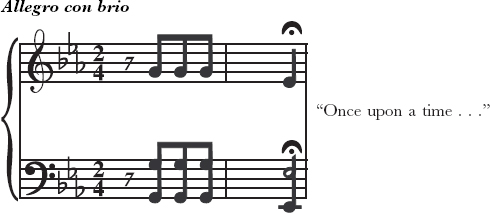

Fairy tales are metaphors. “Once upon a time . . .” locates them in inner time. The information that follows is not useful real-world information, but inner-world process information. Story-telling is an age-old art. Stories entertain, give knowledge, express truths, give hints of possibilities, and potential beyond habitual ways of acting.

Story telling needs the skills of the Milton Model and more. Pacing and leading, synesthesias, anchoring, trance, and smooth transitions are all needed to make a good story. The plot must be (psycho)logical and match the listener's experience.

To create a helpful story, first examine the person's present state and desired state. A metaphor will be a story of the journey from one to the other.

Sort out the elements of both states, the people, the places, the objects, activities, time, not forgetting the representational systems and submodalities of the various elements.

Next, choose an appropriate context for the story, one that will interest the other person, and replace all the elements in the problem with different elements, but hold the relationships the same. Plot the story so that it has the same form as the present state and leads through a connecting strategy to a resolution (the desired state). The story-line beguiles the left brain and the message goes to the unconscious.

Perhaps I can illustrate this process with an example, even though the printed word loses tonality, congruity, and the Milton Model patterns of the storyteller. I would not, of course, try to tell a metaphor that was relevant to you, the reader. This is an example of the process of making a metaphor.

Once I was working with a person who was expressing concern about the lack of balance in his life. He was finding it difficult to decide the important issues in the present, and was worried about devoting a lot of energy to some projects and little to others. Some of his enterprises seemed ill-prepared to him, and others overprepared.

This reminded me of when I was a young boy. I was learning to play the guitar and sometimes I was allowed to stay up late to entertain guests by playing to them over supper. My father was a film actor and many household names used to eat and talk far into the night about all sorts of subjects at those parties. I used to enjoy these times and I got to meet many interesting people.

One night, one of my father's guests was a fine actor, renowned for his skill both in films and on the stage. He was a particular hero of mine, and I enjoyed listening to him talk.

Late in the evening, another guest asked him the secret of his extraordinary skill. “Well”, said the actor, “funnily enough I learned a lot by asking someone the very same question in my youth. As a boy, I loved the circus—it was colorful, noisy, extravagant, and exciting. I imagined I was out there in the ring under the lights, acknowledging the roar of the crowd. It felt marvelous. One of my heroes was a tight-rope walker in a famous traveling circus company; he had extraordinary balance and grace on the high wire. I made friends with him one summer, I was fascinated by his skill and the aura of danger about him, he rarely used a safety net. One afternoon in late summer, I was sad, for the circus was going to leave our town the next day. I sought out my friend and we talked into the dusk. At that time, all I wanted was to be like him; I wanted to join a circus. I asked him what was the secret of his skill.

“First”, he said, “I see each walk as the most important one of my life, the last one I will do, I want it to be the best. I plan each walk, very carefully. Many things in my life I do from habit, but this is not one of them. I am careful what I wear, what I eat, how I look. I mentally rehearse each walk as a success before I do it, what I will see, what I will hear, how I will feel. This way I will get no unpleasant surprises. I also put myself in place of the audience, and imagine what they will see, hear, and feel. I do all my thinking beforehand, down on the ground. When I am up on the wire I clear my mind and put all my attention out”.

“This was not exactly what I wanted to hear at the time, although strangely enough, I always remember what he said.

“You think I don't lose my balance?” he asked me.

“I've never seen you lose your balance”, I replied.

“You're wrong”, he said. “I am always losing my balance. I simply control it within the bounds I set myself. I couldn't walk the rope unless I lost my balance all the time, first to one side and then to the other. Balance is not something you have like the clowns have a false nose; it is the state of controlled movement to and fro. When I have finished my walk, I review it to see if there is anything I can learn from it. Then I forget it completely”.

“I apply the same principles to my acting”, said my hero.

Finally we would like to leave you with a story from The Magus, by John Fowles. This lovely story says a lot about NLP, but remember, it's only one way of talking about it. We leave it to echo in your unconscious.

Once upon a time there was a young prince who believed in all things but three. He did not believe in princesses, he did not believe in islands, he did not believe in God. His father, the king, told him that such things did not exist. As there were no princesses or islands in his father's domains, and no sign of God, the young prince believed his father.

But then, one day, the prince ran away from his palace. He came to the next land. There, to his astonishment, from every coast he saw islands, and on these islands, strange and troubling creatures whom he dared not name. As he was searching for a boat, a man in full evening dress approached him along the shore.

“Are those real islands?” asked the young prince.

“Of course they are real islands”, said the man in evening dress. “And those strange and troubling creatures?”

“They are all genuine and authentic princesses”.

“Then God also must exist!” cried the prince.

“I am God”, replied the man in full evening dress, with a bow.

The young prince returned home as quickly as he could.

“So you are back”, said his father, the king.

“I have seen islands, I have seen princesses, I have seen God”, said the prince reproachfully.

The king was unmoved.

“Neither real islands, nor real princesses, nor a real God, exist”.

“I saw them!”

“Tell me how God was dressed”.

“God was in full evening dress”.

“Were the sleeves of his coat rolled back?”

The prince remembered that they had been. The king smiled.

“That is the uniform of a magician. You have been deceived”.

At this, the prince returned to the next land, and went to the same shore, where once again he came upon the man in full evening dress.

“My father, the king, has told me who you are”, said the young prince indignantly. “You deceived me last time, but not again. Now I know that those are not real islands and real princesses, because you are a magician”.

The man on the shore smiled.

“It is you who are deceived, my boy. In your father's kingdom there are many islands and many princesses. But you are under your father's spell, so you cannot see them”.

The prince returned pensively home. When he saw his father, he looked him in the eyes. “Father, is it true that you are not a real king, but only a magician?”

The king smiled and rolled back his sleeves.

“Yes my son, I am only a magician”.

“Then the man on the shore was God”.

“The man on the shore was another magician”.

“I must know the real truth, the truth beyond magic”.

“There is no truth beyond magic”, said the king.

“The prince was full of sadness.

He said, “I will kill myself “.

The king by magic caused death to appear. Death stood in the door and beckoned to the prince. The prince shuddered. He remembered the beautiful but unreal islands and the unreal but beautiful princesses.

“Very well”, he said. “I can bear it”.

“You see, my son”, said the king, “you too now begin to be a magician”.

From The Magus © John Fowles, published by Jonathan Cape, 1977.

There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

William Shakespeare

Mankind has always searched for meaning. Events happen, but until we give them meaning, relate them to the rest of our life, and evaluate the possible consequences, they are not important. We learn what things mean from our culture and individual upbringing. To ancient peoples, astronomical phenomena had great meaning: comets were portents of change, and the relationship of the stars and planets influenced individual destinies. Now scientists do not take eclipses and comets personally. They are beautiful to see and confirm the universe still obeys the laws we have made up for it.

What does a rainstorm mean? Bad news if you are out in the open without a raincoat. Good news if you are a farmer and there has been a drought. Bad news if you are the organizer of an open-air party.

Good news if your cricket team is close to defeat and the match is called off. The meaning of any event depends on the frame you put it. in. When you change the frame, you also change the meaning. When the meaning changes so do your responses and behavior. The ability to reframe events gives greater freedom and choice.

One person we knew well fell and injured his knee quite badly. This was painful, and meant he could not play squash, a game he enjoyed very much. He framed the accident as an opportunity rather than a limitation, consulted a number of doctors and physiotherapists, and found out how the muscles and ligaments of the knee worked. Fortunately, he did not need surgery. He devised an exercise program for himself and six months later his knee was stronger than it had been, and he was fitter and healthier too. He corrected the postural habits that had led to his knee becoming weak in the first place. Even his squash improved. Hurting his knee was very useful. Misfortune is a point of view.

Metaphors are refraining devices. They say in effect, “This could mean that . . .” Fairy tales are beautiful examples of reframes. What seems to be unlucky turns out to be helpful. An ugly duckling is a young swan. A curse is really a blessing in disguise. A frog can be a prince. And if whatever you touch turns to gold, you are in big trouble.

Inventors make reframes. There is the well-known example of the man who woke one night with the sharp end of a rusty spring in his old mattress digging into him. What possible use could an old bedspring have? (Besides depriving him of sleep.) He reframed it as a stylish egg-cup and started a successful company on the strength of the idea.

Jokes are reframes. Nearly all jokes start by setting events in a certain frame and then suddenly and drastically changing it. Jokes involve taking an object or situation and putting it suddenly in a different context, or suddenly giving it another meaning.

Why do anarchists drink herbal tea? (Answer at end of chapter.)

Here are some examples of different viewpoints on the same statement:

“My job is going badly and I feel depressed”.

Generalize: Perhaps you're just feeling down generally, but your job is OK.

Apply to self: May be you are making yourself depressed by thinking that.

Elicit values or criteria: What is important about your job that you think is going wrong?

Positive outcome: It could make you work harder to get over this particular problem.

Change outcome: Perhaps you need to change jobs.

Setting a further outcome: Can you learn something useful from the way your job is going at the moment?

Tell a metaphor: It's a bit like learning to walk . . .

Redefine: Your depression might mean you are feeling angry because your job is making unreasonable demands on you.

Step down: Which particular parts of your job are going badly?

Step up: How are things generally?

Counter examples: Has your work ever gone badly without you being depressed?

Positive intention: That shows you care about your job.

Time frame: It's a phase, it will pass.

Reframing is not a way of looking at the world through rose-colored spectacles, so that everything is “really” good. Problems will not vanish of their own accord, they still have to be worked through, but the more ways you have of looking at them, the easier they are to solve.

Reframe to see the possible gain, and represent an experience in ways that support your own outcomes and those you share with others. You are not free to choose when you see yourself pushed by forces beyond your control. Reframe so you have some room to manoeuvre.

There are two main types of reframe: context and content.

Nearly all behaviors are useful somewhere. There are very few which do not have value and purpose in some context. Stripping off your clothes in a crowded high street will get you arrested, but in a nudist camp you might be arrested if you do not. Boring your audience in a seminar is not recommended, but the ability is useful for getting rid of unwelcome guests. You will not be popular if you tell bizarre lies to your friends and family, but you will be if you use your imagination to write a fictional bestseller. What about indecision? It might be useful if you could not make up your mind whether to lose your temper . . . or not . . . and then forget all about it.

Context reframing works best on statements like, “I'm too . . .” Or, “I wish I could stop doing . . .” Ask yourself:

“When would this behavior be useful?”

“Where would this behavior be a resource?”

When you find a context where the behavior is appropriate, you could mentally rehearse it in just that context, and make up fitting behavior in the original context. The New Behavior Generator can be helpful here.

If a behavior looks odd from the outside, it is usually because the person is in downtime and has set up an internal context which does not match the world outside. Transference in psychotherapy is an example. The patient responds to the therapist in the same way that he or she responded to parents many years ago. What was appropriate for a child is no longer useful to the adult. The therapist must reframe the behavior, and help the patient develop other ways of acting.

The content of an experience is whatever you choose to focus on. The meaning can be whatever you like. When the two-year-old daughter of one of the authors asked him what it meant to tell a lie, he explained in grave, fatherly tones (taking due account of her age and understanding), it meant saying something that was not true on purpose, to make someone else think something was right when it wasn't. The little girl considered this for a moment and her face lit up.

“That's fun!” she said. “Let's do it!”

The next few minutes were spent telling each other outrageous lies. Content reframing is useful for statements like, “I get angry when people make demands on me”. Or, “I panic when I have a deadline to meet”.

Notice that these types of statement use cause—effect Meta Model violations. Ask yourself:

“What else could this mean?”

“What is the positive value of this behavior?”

“How else could I describe this behavior?”

Politics is the art of content reframing par excellence. Good economic figures can be taken as an isolated example showing up an overall downward trend, or, as an indication of prosperity, depending on which side of the House of Commons you sit. High interest rates are bad for borrowers, but good for savers. Traffic jams are an awful nuisance if you are stuck in one, but they have been described by a government minister as a sign of prosperity. If traffic congestion were eliminated in London, he was reported as saying, this would mean the death of the capital as a job centre.

“We are not retreating”, said a general, “We are advancing backward”.

Advertising and selling are other areas where reframing is very important. Products are put in the best possible light. Advertisements are instant frames for a product. Drinking this coffee means that you are sexy, using this detergent means that you care about your family, using this bread means that you are intelligent. Reframing is so pervasive you will see examples wherever you look.

Simple reframes are unlikely to make a drastic change, but if they are delivered congruently, perhaps with a metaphor, and bring in important issues to that person, they can be very effective.

At the heart of reframing is the distinction between behavior and intention: what you do, and what you are actually trying to achieve by doing it. This is a crucial distinction to make when dealing with any behavior. Often what you do does not get you what you want. For example, a woman may constantly worry about her family. This is her way of showing she loves and cares for them. The family see it as nagging and resent it. A man may seek to demonstrate his love for his family by working very long hours. The family may wish he spent more time with them, even if it meant having less spending money.

Sometimes behavior does get you what you want, but does not fit in well with the rest of your personality. For example, an office worker may flatter and humour the boss to get a rise, but hate himself for doing it. Other times you actually may not know what a behavior is trying to achieve, it just seems a nuisance. There is always a positive intention behind every behavior—why else would you do it? Everything you do is fashioned toward some goal, only it may be out of date. And some behaviors (smoking is a good example) achieve many different outcomes.

The way to get rid of unwanted behaviors is not to try and stop them with will-power. This will guarantee they persist because you are giving them attention and energy. Find another, better way to satisfy the intention, one that is more attuned to the rest of your personality. You do not rip out the gas lights until you have installed electricity, unless you want to be left in the dark.

We contain multiple personalities living in uneasy alliance under the same skin. Each part is trying to fulfil its own outcome. The more these can be aligned and work together in harmony the happier a person will be. We are a mixture of many parts, and they often conflict. The balance shifts constantly; it makes life interesting. It is difficult to be totally congruent, totally committed to one course of action, and the more important the action, the more parts of our personality have to be involved.

Habits are difficult to give up. Smoking is bad for the body, but it does relax you, occupy your hands and sustain friendships with others, Giving up smoking without attending to these other needs leaves a vacuum. To quote Mark Twain, “Giving up smoking is easy. I do it every day”.

We are as unlike ourselves as we are unlike others.

Montaigne

NLP uses a more formal reframing process to stop unwanted behavior by providing better alternatives. This way, you keep the benefits of the behavior. It is a bit like going on a journey. Horse and cart seems to be the only way to get where you want to go, uncomfortable and slow as it is. Then, a friend tells you there is actually a train service and regular flights—different and better ways of reaching your destination.

Six step reframing works well when there is a part of you that is making you behave in a way you do not like. It can also be used on psychosomatic symptoms.

1. First identify the behavior or response to be changed.

It is usually in the form: “I want to . . . but something stops me”. Or, “I don't want to do this, but I seem to end up doing it just the same”. If you are working with someone else, you do not need to know the actual problem behavior. It makes no difference to the reframing process what the behavior is. This can be secret therapy.

Take a moment to express appreciation for what this part has done for you and make it clear that you are not going to get rid of it. This may be difficult if the behavior (let's call it X) is very unpalatable, but you can appreciate the intention, if not the way it was accomplished.

2. Establish communication with the part responsible for the behavior.

Go inside and ask, “Will the part responsible for X communicate with me in consciousness, now?” Notice what response you get. Keep all your senses open for internal sights, sounds, feelings. Do not guess. Have a definite signal, it is often a slight body feeling. Can you reproduce that exact signal consciously? If you can, ask the question again until you get a signal that you cannot control at will.

This sounds strange, but the part responsible is unconscious. If it were under conscious control, you would not be reframing it, you would just stop it. When parts are in conflict there is always some indication that will reach consciousness. Have you ever agreed with someone's plan while harbouring doubts? What does this do to your tone of voice? Can you control that sinking feeling in the pit of your stomach if you agree to work when you would rather be relaxing in the garden? Head shaking, grimacing, and tonality changes are obvious examples of ways that conflicting parts express themselves. When there is a conflict of interest, there is always some involuntary signal and it is likely to be very slight. You have to be alert. The signal is the but in the “Yes, but . . .”

Now you need to turn that response into a yes/no signal. Ask the part to increase the strength of the signal for “yes” and decrease it for “no”. Ask for both signals one after the other, so they are clear.

3. Separate the positive intention from the behavior.

Thank the part for co-operating. Ask, “Will the part that is responsible for this behavior let me know what it is trying to do?” If the answer is the “yes” signal, you will get the intention, and it may be a surprise to your conscious mind. Thank the part for the information, and for doing this for you. Think about whether you actually want a part to do this.

However, you do not need to know the intention. If the answer to your question is “no”, you could explore circumstances where the part would be willing to let you know what it is trying to achieve. Otherwise assume a good intention. This does not mean you like the behavior, simply that you assume the part has a purpose, and that it benefits you in some way.

Go inside and ask the part, “If you were given ways that enabled you to accomplish this intention, at least as well, if not better than what you are doing now, would you be willing to try them out?” A “no” at this point will mean your signals are scrambled. No part in its right mind could turn down such an offer.

4. Ask your creative part to generate new ways that will accomplish the same purpose.

There will have been times in your life when you were creative and resourceful. Ask the part you are working with to communicate its positive intention to your creative, resourceful part. The creative part will then be able to make up other ways of accomplishing the same intention. Some will be good, some not so good. Some you may be aware of consciously, but it does not matter if you are not. Ask the part to choose only those it considers to be as good, or better than the original behavior. They must be immediate and available. Ask it to give the “yes” signal each time it has another choice. Continue until you get at least three “yes” signals. You can take as long as you wish over this part of the process. Thank your creative part when you have finished.

5. Ask the X part if it will agree to use the new choices rather than the old behavior over the next few weeks.

This is future pacing, mentally rehearsing a new behavior in a future situation.

If all is well up to now, there is no reason why you will not get a “yes” signal. If you get a “no”, assure the part it can still use the old behavior, but you would like it to use the new choices first. If you still get a no, you can reframe the part that objects by taking it through the whole six step reframing process.

6. Ecological check

You need to know if there are any other parts that would object to your new choices. Ask, “Does any other part of me object to any of my new choices?” Be sensitive to any signals. Be thorough here. If there is a signal, ask the part to intensify the signal if it really is an objection. Make sure the new choices meet with the approval of all interested parts, or one will sabotage your work.

If there is an objection you can do one of two things. Either go back to step 2 and reframe the part that objects, or ask the creative part, in consultation with the objecting part, to come up with more choices. Make sure these new choices are also checked for any new objections.

Six step reframing is a technique for therapy and personal development. It deals directly with several psychological issues.

One is secondary gain: the idea that however bizarre or destructive a behavior appears, it always serves a useful purpose at some level, and this purpose is likely to be unconscious. It does not make sense to do something that is totally contrary to our interests. There is always some benefit, our mixture of motives and emotions is rarely a harmonious one.

Another is trance. Anyone doing six step reframing will be in a mild trance, with his focus of attention inwards.

Thirdly, six step reframing also uses negotiation skills between parts of one person. In the next chapter we will look at negotiation skills between people in a business context.

We can never be anywhere else but “now” and we have a time machine inside our skulls. When we sleep time stands still. And in our daydreams and night dreams we can jump between present, past, and future without any difficulty. Time seems to fly, or drag its feet, depending on what we are doing. Whatever time really is, our subjective experience of it changes all the time.

We measure time for the outside world in terms of distance and motion—a moving pointer on a clock face—but how do our brains deal with time? There must be some way, or we would never know whether we had done something, or were going to do it; whether it belonged to our past or our future. A feeling of déjà vu about the future would be difficult to live with. What is the difference in the way we think of a past event and a future event?

Perhaps we can get some clues from the many sayings we have about time: “I can't see any future”, “He's stuck in the past”, “Looking back on events”, “Looking forward to seeing you”. Maybe vision and direction has something to do with it.

Now, select some simple repetitive behavior that you do nearly every day, such as brushing your teeth, combing your hair, washing your hands, having breakfast, or watching TV.

Think of a time about five years ago when you did this. It does not have to be a specific instance. You know that you did it five years ago, you can pretend to remember.

Now think of doing that same thing one week ago.

Now think what it would be like if you do it right this instant.

Now one week hence.

Now think about doing it in five years' time. It does not matter that you do not know where you may be, just think of doing that activity.

Now take those four examples. You probably have some sort of picture of each instance. It may be a movie or a snapshot. If a gremlin suddenly shuffled them all around when you were not looking, how could you tell which was which?

You may be interested to find out for yourself how you do it. Later, we will give you some generalizations.

Look at those pictures again. What are the differences between each of the pictures in terms of the following submodalities?

Where are they in space?

How large are they?

How bright?

How focused?

Are they all colored equally?

Are they moving pictures or still?

How far away are they?

It is difficult to generalize about timelines, but a common way of organizing pictures of the past, present, and future is by location. The past is likely to be on your left. The further into the past, the further away the pictures will be. The “dim and distant” past will be furthest. The future will go off to your right, with the far future far away at the end of the line. The pictures on each side may be stacked or offset in some way so that they can be seen and sorted easily. Many people use the visual system for representing a sequence of memories over time, but there may well be some submodality differences in the other systems as well. Sounds may be louder when closer to the present, feelings may be stronger.

Happily, this way of organizing time allies itself with normal eye accessing cues (and reading English), which may explain why it is a common pattern. There are many ways to organize your time line. While there are no “wrong” time lines they all have consequences. Where and how you store your timeline will affect how you think . . .

For example, suppose your past was straight out in front of you. It would always be in view, and attracting your attention. Your past would be an important and influential part of your experience.

Big, bright pictures in the far future would make it very attractive and draw you toward it. You would be future-oriented. The immediate future would be difficult to plan. If there were big, bright pictures in the near future, long-range planning might be difficult. In general, whatever is big, bright, and colorful (if these are critical submodalities for you) will be most attractive and you will pay most attention to it. You can really tell if someone has a murky past or a bright future.

The submodalities may change gradually. For example, the brighter the picture, or the sharper the focus, the nearer to the present. These two submodalities are good at representing gradual change.

Sometimes a person might sort their pictures in a more discrete way using definite locations, each memory detached from the last. Then the person will tend to use staccato gestures when talking about the memories, rather than using more fluent, sweeping gestures.

The future may be spaced out a long way in front of you, giving you trouble meeting deadlines, which will seem far away until they suddenly loom large. On the other hand if the future is too compressed with not enough space between future pictures, you may feel pressed for time, everything looks like it has to be done at once. Sometimes it is useful to compress the timeline, other times, to expand it. It depends what you want. It is common sense that people who are oriented toward the future generally recover from illness more quickly, and medical studies have confirmed this. Timeline therapy could aid recovery from serious illness.

Timelines are important to a person's sense of reality, and so they are difficult to change unless the change is ecological. The past is real in a way that the future is not. The future exists more as potential or possibilities. It is uncertain. Future submodalities will usually reflect this in some way. The timeline may split into different branches, or the pictures may be fuzzy.

Timelines are important in therapy. If a client cannot see a future for himself, a lot of techniques are not going to work. Many NLP therapy techniques presuppose an ability to move through time, accessing past resources or constructing compelling futures. Sometimes the timeline has to be sorted out before this can be done.

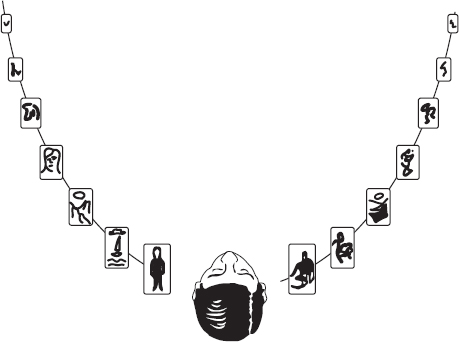

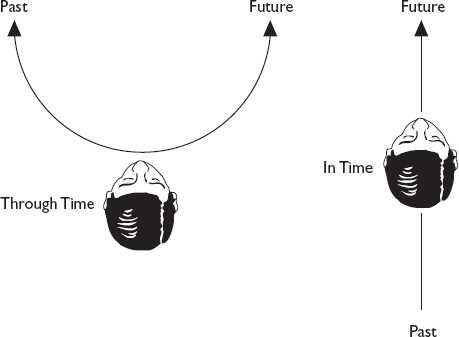

In his book The Basis of Personality, Tad James describes two main types of timelines. The first he calls “through time”, or the Anglo-European type of time where the timeline goes from side to side. The past is on one side, the future on another and both are visible in front of the person. The second type he calls “in time”, or Arabic time, where the timeline stretches from front to back so that one part (usually the past) is behind you, and invisible. You have to turn your head to see it.

Through time people will have a good sequential, linear idea of time. They will expect to make and keep appointments precisely. This is the timeline that is prevalent in the business world. “Time is money”. A through time person is also more likely to store their past as dissociated pictures.

In time people do not have the advantage of the past and future spread out in front of them. They are always in the present moment, so deadlines, business appointments and time-keeping are less important than they are for a through time person. They are associated to their timeline, and their memories are more likely to be associated. This model of time-keeping is common in Eastern, especially Arabic, countries, where business deadlines are more flexible than in the Western world. This can be very exasperating for a Western businessman. The future is looked on much more like a series of “nows” so the urgency goes out of acting this very minute. There are plenty more “nows” where those come from.

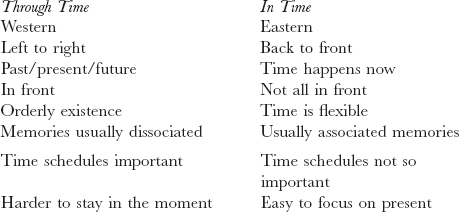

A summary of some generalizations about in time and through time differences:

Language affects brains. We respond to language at an unconscious level. Ways of talking about events will program how we represent them in our minds, and therefore how we respond to them. We have already investigated some of the consequences of thinking with nominalizations, universal quantifiers, modal operators, and other such patterns. Even verb tenses are not exempt, were they?

Now, think of a time when you were walking.

The form of that sentence is likely to make you think of an associated moving picture. If I say, think of the last time you took a walk, you are likely to make a dissociated, still picture. The form of words has taken the movement out of the picture. Yet both sentences mean the same thing, don't they?

Now, think of a time when you will take a walk. Still dissociated. Now a time when you will be walking. Now your idea is likely to be an associated movie.

Now I am going to invite you to be in the distant future, thinking about a past memory, which has actually not yet occurred. Tricky?

Not at all; read the next sentence:

Think of a time when you will have taken a walk.

Now, remember when you are. You influence others and orient them in time with what you say. Knowing this, you have a choice about how you wish to influence them. You cannot stop yourself doing it. All communication does something. Does it do what you want it to do? Does it serve your outcome?

Imagine an anxious person visiting two different therapists. The first says, “So you have felt anxious? Is that how you have been feeling?”

The second says, “So you feel anxious? What things will make you feel anxious?”

The first dissociates her from the experience of feeling anxious and puts it the past. The second associates her into feeling anxious and programs her to feel anxious in the future.

I know which therapist I would rather see.

This is just a small taste of how we influence each other with language in ways we are normally unaware of.

So now, as you think about how elegant and effective your communication can be . . . and you look back with these resources on what you used to do before you changed . . . what was it like to have been like that . . . and what steps did you take to change . . . as you sit here now . . . with this book in hand?

Why do anarchists drink herbal tea? Answer: Because property is theft.