Everyone lives in the same world, and because we make different models of it, we come into conflict. Two people can look at the same event, hear the same words, and make completely different meanings. From these models and meanings we get the rich plurality of human values, politics, religions, interests, and motives. This chapter explores negotiation and meetings to reconcile conflicting interests, and some of the ways these are being successfully used in the world of business.

Some of the most important parts of our map are the beliefs and values that shape our lives and give them purpose. They govern what we do and may bring us into conflict with others. Values define what is important to us; conflict starts if we insist that what is important to us should be important to others too. Sometimes our own values coexist uneasily, and we have to make difficult choices. Do I tell a lie for a friend? Should I take the boring job with more money, or the exciting work that is badly paid?

Different parts of us embody different values, follow different interests, have different intentions, and so come into conflict. Our ability to go for an outcome is radically affected by how we reconcile and creatively manage these different parts of ourselves. It is rare to be able to go wholeheartedly or completely congruently for an outcome, and the larger the outcome, the more parts of ourselves will be drawn in and the more possibility of conflicting interests. We have already dealt with the six step refraining technique, and in the next chapter we will further explore how to resolve some of these internal conflicts.

Internal congruence gives strength and personal power. We are congruent when all our verbal and nonverbal behavior supports our outcome. All parts are in harmony and we have free access to our resources. Small children are nearly always congruent. When they want something they want it with their whole being. Being in harmony does not mean all the parts are playing the same tune. In an orchestra, the different instruments blend together, the total tune is more than any one instrument could produce on its own, and it is the difference between them which gives the music its color, interest, and harmony. So when we are congruent, our beliefs, values, and interests act together to give us the energy to pursue our aims.

When you make a decision and you are congruent about it, then you know you can proceed with every chance of success. The question becomes, how do you know when you are congruent? Here is a simple exercise to identify your internal congruence signal:

Remember a time when you really wanted something. That particular treat, present or experience you really looked forward to. As you think back and associate to that time and event, you can begin to recognize what it feels like to be congruent. Become familiar with this feeling so that you can use it in the future to know if you are fully congruent about an outcome. Notice how you feel, notice the submodalities of the experience as you think back to it. Can you find some internal feeling, sight or sound that will unmistakably define that you are congruent?

Incongruence is mixed messages—an instrument out of tune in an orchestra, a splash of color that does not fit into the picture. Mixed internal messages will project an ambiguous message to the other person and result in muddled actions and self-sabotage. When you face a decision and are incongruent about it, this represents invaluable information from your unconscious mind. It is saying that it is not wise to proceed and that it is time to think, to gather more information, to create more choices, or explore other outcomes. The question here is, how do you know when you are incongruent? Do the following exercise to increase your awareness of your incongruence signal.

Think back to a time when you had reservations about some plan. You may have felt it was a good idea, but something told you it could lead to trouble. Or you could see yourself doing it, but still got that uncertain feeling. As you think about the reservations you had, there will be a certain feeling in part of your body, maybe some particular image or sound that lets you know that you are not fully committed. That is your incongruence signal. Make yourself familiar with it; it's a good friend, and could save you a lot of money. You may want to check it for several different experiences in which you know you had doubts or reservations. Being able to detect incongruence in yourself will save you from making many mistakes.

Used-car salesmen have a poor reputation for congruence. Incongruence also comes out in Freudian slips; someone who extols “state of the ark technology” is clearly not really impressed with the software. Detecting incongruence in others is essential if you are to deal with them sensitively and effectively. For example, a teacher explaining an idea will ask if the student understands. The student may say “Yes”, but her tone of voice or expression may contradict the words. In selling, a salesman who does not detect and deal with incongruence in the buyer is unlikely to make a sale, or if he does, he will generate buyer's remorse, and no further business.

Our values powerfully affect whether we are congruent about an outcome. Values embody what is important to us and are supported by beliefs. We acquire them, like beliefs, from our experiences and from modeling family and friends. Values are related to our identity, we really care about them; they are the fundamental principles we live by. To act against our values will make us incongruent. Values give us motivation and direction, they are the important places, the capital cities, in our map of the world. The most lasting and influential values are freely chosen and not imposed. They are chosen with awareness of the consequences, and carry many positive feelings.

Yet values are usually unconscious and we seldom explore them in any clear way. To rise in a company you will need to adopt company values. If these are different to your own this could lead to incongruence. A company may only be employing half a person if a key worker has values that clash with his work.

NLP uses the word criteria to describe those values that are important in a particular context. Criteria are less general and wide-ranging than values. Criteria are the reasons you do something, and what you get out of it. They are usually nominalizations like wealth, success, fun, health, ecstasy, love, learning, etc. Our criteria govern why we work, whom we work for, whom we marry (if at all), how we make relationships, and where we live. They determine the car we drive, the clothes we buy, or where we go for a meal out.

Pacing another person's values or criteria will build good rapport. If you pace his body but mismatch his values, you are unlikely to get rapport. Pacing other people's values does not mean you have to agree with them, but it shows you respect them.

Make a list of the 10 or so most important values in your life. You can do this alone, or with a friend to help you. Elicit your answers by asking such questions as:

What's important to me?

What truly motivates me?

What has to be true for me?

Criteria and values need to be expressed positively. Avoiding ill health might be a possible value, but it would be better to phrase it as good health. You may find it fairly easy to come up with the values that motivate you.

Criteria are likely to be nominalizations, and you need the Meta Model to untangle them. What do they mean in real, practical terms? The way to find this out is by asking for the evidence that lets you know the criterion has been met. It may not always be easy to find the answers, but the question to ask is:

How would you know if you got them?

If one of your criteria is learning, what are you going to learn about and how will you do it? What are the possibilities? And how will you know when you have learned something? A feeling? The ability to do something that you have not been able to do? These specific questions are very valuable. Criteria tend to disappear in a smoke screen when they come into contact with the real world.

When you have found out what these criteria really mean to you, you can ask whether they are realistic. If by success you mean a fivefigure salary, a Ferrari, a town house, a country cottage, and a highpowered job on Wall Street all before your next birthday, you may well be disappointed. Disappointment, as Robert Dilts likes to say, requires adequate planning. To be really disappointed, you must have fantasized at great length about what you want to happen.

Criteria are vague and can be interpreted very differently by other people. I remember a good example from a couple I know well. For her, competence meant that she had actually done some task successfully. It was simply descriptive and not a highly valued criterion. For him, competence meant the feeling that he could do a task if he put his mind to it. Feeling competent in this way gave him self-esteem and it was highly valued. When she called him incompetent, he got very upset—until he understood what she actually meant. How different people see the criterion of male and female attractiveness is the force that makes the world go around.

Many things are important to us, and one useful step is to get a sense of the relative importance of your criteria. Since criteria are contextrelated, the ones you apply to your work will be different to the ones you apply to your personal relationships. We can use criteria to explore an issue like commitment to a job or a group of people. Here is an exercise to explore the criteria in this issue:

You can use criteria in many ways. Firstly, we often do things for crummy reasons. Reasons that do not fully express our values. Equally we may want to do something in a vague sort of way, but it does not get done because other more important criteria stand in the way. This links back to outcomes in the first chapter. An outcome may need to be connected to a larger outcome that is sufficiently motivating because it is backed by important criteria. Criteria provide the energy for outcomes. If you can make something important to you by linking it to high criteria, obstacles will vanish.

Suppose you think it would be a good idea if you took regular exercise to get fit. Somehow, time goes on and you do not get around to it, because it is difficult to find the time in a busy week. Connecting regular exercise with looking attractive and having extra stamina for playing an enjoyable sport is likely to be far more motivating and can override the time factor, so that you create the time. There is usually time for what we really want to do. We do not have time for things that do not motivate us sufficiently.

The way you think about your criteria will have a submodality structure. The important ones may be represented by a bigger, closer or brighter picture, or a louder sound, or a stronger feeling, perhaps localized in a particular part of your body. What are the submodalities of your criteria, and how do you know which criteria are important to you? There are no rules that work in every case. It is worth exploring these ideas for yourself.

When you connect your actions to criteria, it is rather like playing a game of chutes and ladders. You can start with some small issue, but if you connect it to important criteria, you are taken very quickly to the top of the board. You will be motivated to do it, and you will think about it with submodalities that make it compelling.

How we connect events and ideas forms the substance of our maps, the roads between the cities. Understanding an issue means not only having the information, but also connecting it to other parts of our map. When we dealt with the size of our outcomes, we connected a smaller outcome to a larger one to give energy, and broke down a large outcome into a series of smaller ones to make it easier to handle. This was an example of a general idea which is known as chunking or stepping in NLP. Chunking is a term from the computer world, meaning to break things into bits. To chunk up or step up is to move from the specific to the general, or from a part to the whole. Chunking or stepping down moves from the general to the specific, or from the whole to a part.

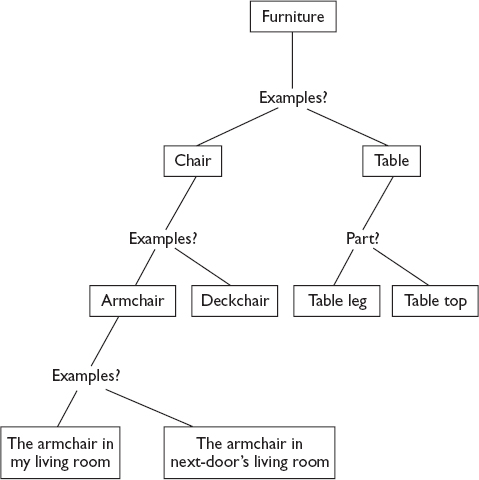

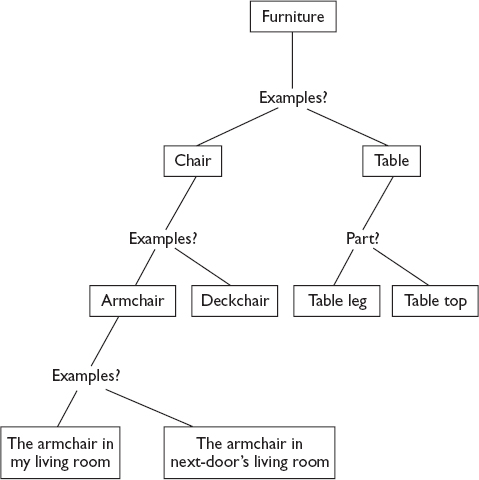

The idea is simple. Take for example, an everyday object such as a chair. To step up to the next level you would ask, “What is this an example of ?” One answer would be, “An item of furniture”. You could also ask, “What is this a part of ?” One answer would be, “A dining suite”. To step down, you ask the question in reverse, “What is a specific example of the class of objects known as chairs?” One answer would be, “An armchair”. The higher level always contains what is at the lower level.

You can also step sideways and ask, “What is another example of this class of things?” To step sideways from a chair might come up with the answer, “Table”. To step sideways from armchair might come to “Deckchair”. The sideways example is always determined by what is at the next level up. You cannot ask for another example unless you know what it is another example of.

The Meta Model uses this idea; it explores the downward direction, making the idea more and more specific. The Milton “Model goes up to the general level so as to take in all the specific examples below it.

If someone asks you for a drink and you give them a coffee, they may actually want a lemonade. Both coffee and lemonade are drinks. You need more specific information.

Stepping down goes to specifics, sensory-based, real-world events. (I want 25 fluid ounces of brand Fizzo lemonade in a tall glass at a temperature of 40° Fahrenheit, with three lumps of ice, shaken, not stirred.) Stepping up can eventually lead to outcomes and criteria (I want a drink because I am thirsty), if you start asking why at a high level.

Jokes, of course, make great use of stepping and then suddenly changing the rules on top. People connect things in weird and wonderful ways (according to our own map anyway). Do not assume they use the same rules as you do to connect ideas. Do not assume you know their rules at all. Like a game of Chinese whispers, the further you go with the rules slightly changing each time, the further away you will be from where you think you are.

Here is an exercise in stepping up in different ways. Coffee can be linked to each of the following in a different way. In the first example, tea and coffee are both members of a more general class called beverages. See if you can find a different step up for coffee and each of the others in turn:

(Answers at the end of the chapter.)

So it is possible to chunk sideways to some very different things and arrive in a very different place. It is like the oft-quoted idea that in this global village, six social relationships will bring you to anybody in the world. (I know Fred (1), who knows Joan (2), who knows Susy (3), who knows Jim (4), etc.)

So once again meaning depends on context. The links we make are important. Walls are held up not so much by the bricks as by the mortar that connects them. What is important to us, and how we connect ideas is important in meetings, negotiations, and selling.

Metaprograms are perceptual filters that we habitually act on. There is so much information we could attend to, and most gets ignored as we have at most nine chunks of conscious attention available. Metaprograms are patterns we use to determine what information gets through. For example, think of a glass full of water. Now imagine drinking half of it. Is the glass half full or half empty? Both, of course, it's a matter of viewpoint. Some people notice what is positive about a situation, what is actually there, others notice what is missing. Both ways of looking are useful and each person will favor one view or the other.

Metaprograms are systematic and habitual, and we do not usually question them if they serve us reasonably well. The patterns may be the same across contexts, but few people are consistently habitual, so metaprograms are likely to change with a change of context. What holds our attention in a work environment may be different from what we pay attention to at home.

So metaprograms filter the world to help us create our own map.

You can notice other people's metaprograms both through their language and behavior. Because metaprograms filter experience and we pass on our experience with language, certain patterns of language are typical of certain metaprograms.

Metaprograms are important in the key areas of motivation and decision-making. Good communicators shape their language to fit the other person's model of the world. So using language that accords with another person's metaprograms preshapes the information and ensures he can easily make sense of it. This leaves him more energy for decision-making and getting motivated.

As you read through these metaprograms you may find yourself sympathizing with one particular view in each category. You may even wonder how anyone could possibly think differently. This is a clue to the pattern you use yourself. Of the two extremes within a metaprogram pattern, there is likely to be one you can't stand or understand. The other is your own.

There are many patterns that might qualify as metaprograms, and different NLP books will emphasize different patterns. We will give some of the most useful ones here. No value judgment is implied about these patterns. None are “better” or “right” in themselves. It all depends on the context and the outcome you want. Some patterns work best given a particular type of task. The question is: can you act in the most useful way for the task you have to do?

This first metaprogram is about action. The proactive person initiates, he jumps in and gets on with it. He does not wait for others to initiate action.

The reactive person waits for others to initiate an action or bides her time before acting. She may take a long time to decide or never actually take any action.

A proactive person will tend to use complete sentences with a personal subject (noun or pronoun), an active verb, and a tangible object, e.g. “I am going to meet the managing director”.

A reactive person will tend to use passive verbs and incomplete sentences. He is also likely to use qualifying phrases and nominalizations, e.g. “Is there any chance that it might be possible to arrange a meeting with the managing director?”

Even in such a short example there are many possibilities for making use of this pattern. A proactive person is motivated by phrases like “Go to it”, “Do it”, and “Time to act”. In a sales situation, proactive people are more likely to go ahead and buy and make quick decisions. A reactive person would respond best to phrases like “Wait”, “Let's analyze”, “Think about it”, and “See what the others think”.

Few people act out these patterns in such an extreme way. Most show a mixture of the two traits.

The second pattern is about motivation and explains how people maintain their focus. People with a toward metaprogram stay focused on their goals. They go for what they want. Away people recognize problems easily and they know what to avoid, for they are clear about what they do not want. This can lead to problems for them in setting well-formed outcomes. Remember the old argument in business, education, and parenting—whether to use the carrot or the stick approach? In other words, is it better to offer people incentives or threats? The answer of course is: it all depends whom you want to motivate. Towards people are energized by goals and rewards. Away people are motivated to avoid problems and punishment. Arguing which is best in general is futile.

It is easy to recognize this pattern from a person's language. Does she talk about what she wants, achieves, or gains? Or does she tell you about the situations she wants to avoid and the problems to steer clear of ? Towards people are best employed in goal-getting. Away from people are excellent at finding errors and work well in a job like quality control. Art critics usually have a strong away orientation as many a performing artist can testify!

This pattern is about where people find their standards. An internal person will have his standards internalized and use them to compare courses of action and decide what to do. He will use his own standards to make a comparison and a decision. In answer to the question, “How do you know you have done a good piece of work?”, he is likely to say something like, “I just know”. Internal people take in information but will insist on deciding for themselves from their own standards. A strongly internal person will resist someone else's decision on their behalf, even if it is a good one.

External people need others to supply the standards and direction.

They know a job is well done when someone tells them so. Externals need to have an external standard. They will ask you about your standards. It looks as though they have difficulty deciding.

Internal people have difficulty accepting management. They are likely to make good entrepreneurs and are attracted to self-employment. They have little need of supervision.

External people need to be managed and supervised. They need the standard for success to come from the outside, otherwise they are unsure if they have done things correctly. One way you can identify this metaprogram is by asking: “How do you know you have done a good job?” Internal people will tell you they decide. External people tell you they know because someone else has confirmed it.

This pattern is important in business. An options person wants to have choices and develop alternatives. He will hesitate to follow well-worn procedural paths, however good they are. The procedures person is good at following set, laid down courses of action, but not very good at developing them, being more concerned with how to do something than why she might want to do it. She is likely to believe there is a “right” way to do things. It is obviously not a good idea to employ a procedures person to generate alternatives to the present system. Nor is it useful to employ an options person to follow a fixed procedure where success depends on following the procedure to the letter. They are not strong on following routines. They may feel compelled to be creative.

You can identify this metaprogram by asking: “Why did you choose your current job?” Options people will give you reasons why they did what they did. Procedures people will tend to tell you how they came to do what they did or just give facts. They answer the question as if it were a “how to” question.

Options people respond to promotional ideas that expand their choices. Procedures people respond to ideas that give them a clear-cut, proven path.

This pattern deals with chunking. General people like to see the big picture. They are most comfortable dealing with large chunks of information. They are the global thinkers. The specific person is most comfortable with small pieces of information, building from small to large, and so is comfortable with sequences, in extreme cases only being able to deal with the next step in the sequence he is following. Specifics people will talk about “steps” and “sequences” and give precise descriptions. They will tend to specify and use proper names.

The general person, as you might expect, generalizes. He may leave out steps in a sequence, making it hard to follow. He will see the whole sequence as one chunk rather than a series of graded steps. The general person deletes a lot of information. I bought some juggling balls some time ago and the instructions that came with them were clearly written by a very general person. They went as follows: “Stand erect, balanced with your feet shoulder width apart. Breathe evenly. Start to juggle”.

General people are good at planning and developing strategies. Specific people are good at small step sequential tasks that involve attention to detail. You can tell from a person's language whether he is a general or a specific thinker. Does he give you details or the big picture?

This pattern is about making comparisons. Some people notice what is the same about things. This is called matching. (It is not related to the rapport pattern.) Mismatchers notice what is different when making comparisons. They point out the differences and often get involved in arguments. A person that chunks down and mismatches will go over information with a fine toothcomb looking for discrepancies. If you match and think in big chunks, he will drive you crazy. Look at the three triangles below. Take a moment to answer this question silently to yourself: What is the relationship between them?

There is no right answer, of course, as their relationship involves points of similarity and difference.

The question highlights four possible patterns. There are people who match, who notice things that are the same. They might say that all three triangles are the same. (As indeed they are.) Such people will often be content in the same job or the same type of work for many years, and they are good at tasks that remain essentially the same.

There are people who notice sameness with exception. They notice similarities first, then differences. Looking at the diagram, they may answer that two triangles are the same and one is different, being upside down. (Quite right.) Such people usually like changes to occur gradually and slowly, and like their work situation to evolve over time. When they know how to do a job, they are ready to do it for a long time and are good at most tasks. They will use comparatives a lot, e.g. “better”, “worse”, “more”, “less”. They respond to promotional material that uses words like “better”, “improved” or “advanced”.

Difference people are the mismatchers. They would say all three triangles are different. (Right again.) Such people seek out and enjoy change, often changing jobs rapidly. They will be attracted to innovative products, advertised as “new” or “different”.

Differences with exception people will notice differences first, then similarities. They might say the triangles are different and two of them are the same way up. They seek out change and variety, but not to the extent of the difference people. So to find out this metaprogram ask, “What is the relationship between these two things?

There are two aspects to how a person becomes convinced of something. Firstly, what channel the information comes through, and secondly how the person manages the information once they have it (the mode).

First the channel. Think of a sales situation. What does a customer need to do to be convinced that the product is worthwhile? Or what evidence does a manager need to be convinced that someone is good at her job? The answer to this question is often related to a person's primary representational system. Some people need to see the evidence (visual). Others need to hear from others. Some people need to read a report; for example, the Consumers' Association reports compare and give information about many products. Others have to do something. They may need to use the product to evaluate it or work alongside a new employee before deciding she is competent. The question to ask to determine this metaprogram is: “How do you know someone is good at his job?”

A visual person needs to see examples. A hear person needs to talk to people and gather information. A read person needs to read reports or references about someone. A do person has to actually do the work with a person to be convinced she is good at her job.

The other side to this metaprogram is how people learn new tasks most easily. A visual person learns a new task most easily if he is shown how to do it. A hear person will learn best if she is told what to do. A read person learns best by reading instructions. A do person learns best by going and doing it for him or herself, getting “hands-on experience”.

The second part of this metaprogram is about how the person manages the information and how it needs to be presented. Some people need to be presented with the evidence a particular number of times—perhaps two, three or more—before they are convinced. These are people who are convinced by a number of examples. Other people do not need much information. They get a few facts, imagine the rest and decide quickly. They often jump to conclusions on very little data. This is called the automatic pattern. On the other hand, some people are never really convinced. They will only be convinced for a particular example or a particular context. This is known as the consistent pattern. Tomorrow you may have to prove it to them all over again, because tomorrow is another day. They need convincing all the time. Lastly some people need to have their evidence presented over a period of time—a day, a week—before becoming convinced.

This is a very brief survey of some of the main metaprograms. They were originally developed by Richard Bandler and Leslie Cameron Bandler, and were further developed for use in business by Rodger Bailey as the “Language and Behavior Profile”. Criteria are often referred to as metaprograms, but they are not patterns, they are the values and things that really matter to you, so we have treated them separately.

Orientation in time is often referred to as a metaprogram. Some people will be in time, that is, associated with their timeline. Some people are through time, that is, primarily dissociated from their timeline. Another pattern that is often referred to as a metaprogram is preferred perceptual position. Some people spend most of their time in first position, in their own reality. Others empathize more and will spend a lot of time in second position. Others prefer third position.

Different books will have varying lists of metaprogram patterns, and there is no right answer, except to use those patterns that are useful to you and ignore the rest. Remember everything is likely to change with context. A man who weighs 200 pounds will be heavy in the context of an aerobics class. He will be at the extreme end of scale there. Put him in a gymnasium full of Sumo wrestlers and he will be at the light end of the scale. A person who appears very proactive in one context may seem reactive in another. Similarly, a person may be very specific in a work context, yet very general in his leisure pursuits.

Metaprograms may also change with emotional state. A person may become more proactive under stress and more reactive when comfortable. As with all the patterns presented in this book, the answer is always the person in front of you. The pattern is only the map. Metaprograms are not another way of pigeonholing people. The important questions are: Can you be aware of your own patterns? What choices can you give others? They are useful guiding patterns. Learn to identify only one pattern at a time. Learn to use the skills one at a time. Use them if they are useful.

The proactive person initiates action. The reactive person waits for others to initiate action and for things to happen. He will take time to analyze and understand first.

The toward person stays focused on his or her own goals and is motivated by achievement. The away person focuses on problems to be avoided rather than goals to be achieved.

The internal person has internal standards and decides for him or herself. The external person takes standards from outside and needs direction and instruction to come from others.

Options people want choices and are good at developing alternatives. Procedures people are good at following set courses of procedures. They are not action-motivated and are good at following a fixed series of steps.

General people are most comfortable dealing with large chunks of information. They do not pay attention to details. Specific people pay attention to details and need small chunks to make sense of a larger picture.

People who match will mostly notice points of similarity in a comparison. People who mismatch will notice differences when making a comparison.

Channel:

Visual: Need to see the evidence.

Hear: Need to be told.

Read: Need to read.

Do: Need to act.

Mode:

Number of Examples: Need to have the information some number of times before becoming convinced.

Automatic: Need only partial information.

Consistent: Need to have the information every time to be convinced, and then only for that example.

Period of time: Need to have the information remain consistent for some period of time.

Sales psychology already has given rise to whole libraries of books, and we will only touch on it lightly here, to show some of the possibilities using NLP ideas.

Selling is often misunderstood, like advertising. A popular definition describes advertising as the art of arresting human intelligence long enough to get money from it. In fact, the whole purpose of sales, as the book The One Minute Sales Person by Spencer Johnson and Larry Wilson puts very eloquently, is to help people to get what they want. The more you help people to get what they want, the more successful a sales-person you will be.

Many NLP ideas will work toward this purpose. Initial rapport is important. Anchoring resources will enable you to meet challenges in a resourceful state. Feeling good about your work lets you do good work.

Future pacing can help to create the situations and feelings that you want, by mentally rehearsing them first. Setting well-formed outcomes is an invaluable skill in selling. In Chapter 1 you applied the well-formedness criteria to your own outcomes. The same questions that you used there can be used to help others become clear about what they want. This skill is crucial in selling because you can only satisfy the buyer if you know exactly what they want.

The idea of stepping up and down can help you find out what people need. What are their criteria? What is important to them about a product?

Do they have an outcome in mind about what they are buying, and can you help them to realize it?

I remember a personal example. There is a high street near where I live which has many more than its fair share of hardware shops. The one that does the best business is a small, rather out of the way shop. The owner always makes a genuine attempt to find out what you are doing and what you want the tool or equipment for. Although he does not always get good rapport, for sometimes his interrogation verges on the third degree, he makes sure that he does not sell you anything that does not specifically help you achieve what you want to do. If he does not have the right tool, he will direct you to a shop that does. He survives very well in the face of strong competition from big chain stores with substantially lower prices.

In our model he steps up to find out the criteria and outcome of his customers, and then steps down to exactly the specific tool they need. This may involve a step sideways from what the customer actually asked for in the first place. (It always does when I go there.)

Stepping sideways is very useful to find out what a person likes about a product. What are the good points? Where are the points of difference that means a person chooses one product rather than another? Exploring what a person wants in these three directions is a consistent pattern of top salespeople. Congruence is essential. Would a salesperson use the product he is selling? Does he really believe in the advantages he recites? Incongruence can leak out in tonality and posture, and make the buyer uneasy.

Framing in NLP refers to the way we put things into different contexts to give them different meanings; what we make important at that moment. Here are five useful ways of framing events. Some have been implicit in other aspects of NLP, and it is worth making them explicit here.

This is evaluating in terms of outcomes. Firstly know your own outcome, and make sure it is well-formed. Is it positive? Is it under your control? Is it specific enough and the right size? What is the evidence? Do you have the resources to carry it out? How does it fit with your other outcomes?

Secondly, you may need to elicit outcomes from any other people involved, to help them get clear what they want, so you can all move forward. Thirdly, there is dovetailing outcomes. Once you have your outcome and the other person's outcome, you can see how they fit together. You may need to negotiate over any differences between them.

Lastly, by keeping outcomes in mind you can notice if you are moving toward them. If you are not, you need to do something different.

The outcome frame is an extremely useful pair of spectacles with which to view your actions. In business, if executives do not have a clear view of their outcome, they have no firm basis for decisions and no way of judging if an action is useful or not.

Again this has been dealt with explicitly with outcomes and implicitly throughout the book. How do my actions fit into the wider systems of family, friends, professional interests? Is it expressive of my overall integrity as a human being? And does it respect the integrity of the other people involved? Congruence is the way our unconscious mind lets us know about ecology, and is a prerequisite of acting with wisdom.

This concentrates on clear and specific details. In particular, how will you know when you have attained your outcome? What will you see, hear and feel? This forms part of the outcome frame, and is sometimes useful to apply on its own, especially to criteria.

This frame is a way of creative problem-solving by pretending that something has happened in order to explore possibilities. Start with the words, “If this happened . . .” or, “Let's suppose that . . .” There are many ways this can be useful. For example, if a key person is missing from a meeting, you can ask, “If X were here, what would she do?” If someone knows X well the answers they come up with can be very helpful. (Always check back with X later if important decisions are to be made.)

Another way of using the idea is to project yourself six months or a year into a successful future, and looking back, ask, “What were the steps that we took then, that led us to this state now?” From this perspective you can often discover important information that you cannot see easily in the present because you are too close to it.

Another way is to take the worst case that could happen. What would you do if the worst happened? What options and plans do you have? “As if” can be used to explore the worst case as a specific example of a more general and very useful process known as downside planning. (A process insurance companies make a great deal of money from.)

This frame is simple. You recapitulate the information you have up to that point using the other person's key words and tonalities in the backtrack. This is what makes it different to a summary, which often systematically distorts the other person's words. Backtrack is useful to open a discussion, to update new people in a group, and to check agreement and understanding of the participants in a meeting. It helps build rapport and is invaluable any time you get lost; it clarifies the way forward.

Many messages seem to come to agreement, but the participants go away with totally different ideas about what was agreed. Backtrack can keep you on course toward the desired outcome.

Although we will describe meetings in a business context, the patterns apply equally to any context where two or more people meet for a common purpose. As you read through the rest of this chapter, think of each pattern in whatever context is appropriate to you.

NLP has a lot to offer in a business context. The greatest resource of any business is the people in it. The more effective the people become, the more effective the business will be. A business is a team of people working toward a common goal. Their success will depend mainly on how well they deal with these key points:

The resourcefulness, flexibility, perceptual filters, presentation, and communication skills of the individuals in the business determine how successful it is. NLP addresses the precise skills that create success in the business world.

NLP goes to the heart of a business organization by refining and developing the effectiveness of each individual member carrying out these tasks. Business meetings are one place many of these skills will come together. We will start by dealing with cooperative meetings where most people will broadly agree about the outcome. Meetings where there are apparently conflicting outcomes will be dealt with under negotiation.

Meetings are purposeful and the purpose of cooperative meetings is likely to be explicit, for example, to meet with colleagues once a week to exchange information, make decisions and allocate responsibility.

Other examples would be planning next year's budget, a performance appraisal, or a project review.

As a participant in an important meeting you need to be in a strong, resourceful state, and congruent about the part you have to play. Anchors can help, both before a meeting to get you in a good state, and during a meeting if things start to go awry. Remember other people will be anchors for you, and you are an anchor to others. The room itself may be an anchor. An office is often a place full of the trappings of personal power and success of the person behind the desk. You may need all the resources you can get.

The membership and agenda of the meeting need to be settled in advance. You must be clear about your outcome. You also need an evidence procedure: how you will know if you achieve it. You need to be very clear about what you would want to see, hear and feel. If you have no outcome for the meeting, you are probably wasting your time.

The basic format for successful meetings resembles the three minute NLP seminar in Chapter 1:

1. Know what you want.

2. Know what others want.

3. Find ways in which you can all get it.

This seems simple and obvious, but it is often lost in the rough and tumble, and step 3 may be difficult if there are widely conflicting interests.

When the meeting starts, get consensus on a shared outcome. It is important that all agree on an outcome for the meeting, some common issue to be dealt with. When you have the outcome, anchor it. The easiest way to do this is to use a key phrase, and write it up on a board or flip chart. You will also need to agree on the evidence that will show that the outcome has been achieved. How will everyone know when they have it? Use the evidence frame.

Once again, rapport is an essential step. You will need to establish rapport with the other participants, if you do not have it already, by using nonverbal skills and matching language. Be sensitive to any incongruence in any of the participants about the shared outcome. There may be hidden agendas, and it is better to know about these at the outset, rather than later.

During the discussion, the evidence, ecology, backtrack, and As If frames may be useful. One problem that besets meetings is that they go off track. Before you know it, the time is up and the decision or outcome has not been achieved. Many a meeting has gone off at a tempting tangent and ended up in a cul-de-sac.

The outcome frame can be used to challenge the relevance of any contribution and so keep the meeting on track. Suppose a colleague makes a contribution to the discussion that does not seem to relate to the mutually-agreed outcome. It may be interesting, informative and true, but not relevant. You could say something like, “I have trouble seeing how that could bring us nearer to our outcome; can you tell us how it fits into this meeting?” You can anchor this relevancy challenge visually with a hand or head movement. The speaker must show how his contribution is relevant. If it is not, then valuable time is saved. The contribution may be important in another context, in which case recognize it as such, and agree that it be dealt with at another time. Close and summarize each issue as it arises, fitting it into the agreed outcome, or agree to defer it to another meeting.

If someone is disrupting a meeting or leading it seriously off track, you might say something like, “I appreciate that you feel strongly about this issue and it is clearly important to you. However, we agreed that this is not the place to discuss it. Can we meet later to settle this?” Calibrate for congruence when you make these sorts of proposals. Calibration may tell you that X lights a cigarette when she is happy with the outcome. Y always looks down when he objects (so you ask what he would need to feel OK about the issue). Z bites his nails when unhappy. There are so many ways that you can be aware on a deeper level how the meeting is progressing and sidestep trouble before it arises.

At the close of the meeting, use the backtrack frame and get agreement on progress and the outcome. Clearly define and get agreement on what actions are to be taken and by whom. Sometimes there is not a full agreement, so the close is dependent on certain actions. So you say something like, “If this happened and if X did this and if we persuade Y that this is alright, then we proceed?” This is known as a conditional close.

Anchor the agreement with key words and future pace. What will remind the participants to do what they have agreed? Project the agreement out of the room and make sure it is connected to other independent events that can act as signals to remind the people to take the agreed action.

Research has shown that we remember things best when they occur in the first or last few minutes of a meeting. Take advantage of this and place the important points at the beginning and the end of the meeting.

A) Before the meeting:

1. Set your outcome(s) and the evidence that will let you know that you have reached it (them).

2. Determine the membership and agenda for the meeting.

B) During the meeting:

1. Be in a resourceful state. Use resource anchors if necessary.

2. Establish rapport.

3. Get consensus on a shared outcome and the evidence for it.

4. Use the relevancy challenge to keep the meeting on track.

5. If information is not available, use the As If frame.

6. Use the backtrack frame to summarize key agreements.

7. Keep moving toward your outcome, by using the Meta Model or any other tools needed.

C) Closing the meeting:

1. Check for congruence and agreement of the other participants.

2. Summarize the actions to be taken. Use the backtrack frame to take advantage of the fact that we remember endings more easily.

3. Test agreement if necessary.

4. Use a conditional close if necessary.

5. Future pace the decisions.

Negotiation is communicating for the purpose of getting a joint decision, one that can be congruently agreed on both sides. It is the process of getting what you want from others by giving others what they want, and takes place in any meeting where interests conflict.

Would that it were as easy to do as it is to describe. There is a balance and a dance between your integrity, values, and outcomes, and those of the other participants. The dance of communication goes back and forth, some interests and values will be shared, some opposed. In this sense, negotiation permeates everything we do. We are dealing here with the process of negotiation, rather than what you are actually negotiating over.

Negotiation often takes place about scarce resources. The key skill in negotiation is to dovetail outcomes: to fit them together so that everyone involved gets what they want (although that may not be the same as their demand at the beginning of the negotiation). The presupposition is that the best way to achieve your outcome is to make sure that everyone involved achieves theirs too.

The opposite of dovetailing outcomes is manipulation, where other people's wants are disregarded. There are four dragons that lie in wait for those that practice manipulation: remorse, resentment, recrimination, and revenge. When you negotiate by seeking to dovetail outcomes the other people involved become your allies, not your opponents. If a negotiation can be framed as allies solving a common problem, the problem is already partially solved. Dovetailing is finding that area of overlap.

Separate the people from the problem. It is worth remembering that most negotiations involve people with whom you have, or want, an ongoing relationship. Whether you are negotiating over a sale, a salary, or a vacation, if you get what you want at the other person's expense, or they think you have pulled a fast one, you will lose goodwill that may be worth much more in the long run than success in that one meeting.

You will be negotiating because you have different outcomes. You need to explore these differences, because they will point to areas where you can make trade-offs to mutual advantage. Interests that conflict at one level may be resolved if you can find ways of each party getting their outcome on a higher level. This is where stepping up enables you to find and make use of alternative higher level outcomes. The initial outcome is only one way of achieving a higher level outcome.

For example, in a negotiation over salary (initial outcome), more money is only one way of obtaining a better quality of life (higher level outcome). There may be other ways of achieving a better quality of life if money is not available—longer vacations, or more flexible working hours, for example. Stepping up finds bridges across points of difference.

People may want the same thing for different reasons. For example, imagine two people quarrelling over a pumpkin. They both want it. However, when they explain exactly why they want it, you find that one wants the fruit to make a pie, and the other wants the rind to make a Halloween mask. Really they are not fighting over the same thing at all. Many conflicts disappear when analyzed this way. This is a small example, but imagine all the different possibilities there are in any apparent disagreement.

If there is a stalemate, and a person refuses to consider a particular, step, you can ask the question, “What would have to happen for this not to be a problem?” or, “Under what circumstances would you be prepared to give way on this?” This is a creative application of the As If frame and the answer can often break through the impasse. You are asking the person who made the block to think of a way around it.

Set your limits before you start. It is confusing and self-defeating to negotiate with yourself when you need to be negotiating with someone else. You need what Roger Fisher and William Ury in their marvelous book on negotiation, Getting to Yes, call a BATNA, or Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement. What will you do if despite all the efforts of both parties you cannot agree? Having a reasonable BATNA gives you more leverage in the negotiation, and a greater sense of security.

Focus on interests and intentions rather than behavior. It is easy to get drawn into winning points and condemning behavior, but really nobody wins in these sorts of situations.

A wise and durable agreement will take in community and ecological interests. A mutually satisfying solution will be based on a dovetailing of interests, a win/win, not a win/lose model. So what is important is the problem and not the people, the intentions not the behavior, the interests of the parties not their positions.

It is also essential to have an evidence procedure that is independent of the parties involved. If the negotiation is framed as a joint search for a solution, it will be governed by principles and not pressure. Yield only to principle, not pressure.

There are some specific ideas to keep in mind while negotiating. Do not make an immediate counter-proposal immediately after the other side has made a proposal. This is precisely the time when they are least interested in your offering. Discuss their proposal first. If you disagree, give the reasons first. Saying you disagree immediately is a good way to make the other person deaf to your next few sentences.

All good negotiators use a lot of questions. In fact two good negotiators will often start negotiating over the number of questions. “I've answered three of your questions, now you answer some of mine . . .” Questions give you time to think, and they are an alternative to disagreement. It is far better to get the other person to see the weakness in his position by asking him questions about it, rather than by telling him the weaknesses you perceive.

Good negotiators, also explicitly signal their questions. They will say something like, “May I ask you a question about that?” By doing so they focus the attention of the meeting on the answer and make it difficult for the person questioned to evade the point if he has agreed to answer the question.

It would seem that the more reasons you give for your point of view the better. Phrases like “the weight of the argument” seem to suggest it is good to pile arguments on the scale until it comes down on your side. In fact the opposite is true. The fewer reasons you give, the better, because a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. A weak argument dilutes a strong one, and if you are drawn into defending it, you are on poor ground. Beware of a person who says, “Is that your only argument?” If you have a good one, say, “Yes”. Do not get drawn into giving another, necessarily weaker one. The follow-up may be, “Is that all?” If you take this bait you will just give him ammunition. Hopefully, if the negotiation is framed as a joint search for a solution, this sort of trick will not occur.

Finally, you could use the as if frame and play the devil's advocate to test the agreement (“No, I don't really think this is going to work, it all seems too flimsy to me . . .”). If other people agree with you, you know that there is still work to be done. If they argue, all is well.

A) Before the negotiation:

Establish your BATNA and your limits in the negotiation.

B) During the negotiation:

1. Establish rapport.

2. Be clear about your own outcome and the evidence for it. Elicit outcomes of the other participants together with their evidence.

3. Frame the negotiation as a joint search for a solution.

4. Clarify major issues and obtain agreement on a large frame. Dovetail outcomes, step up if necessary to find a common outcome. Check that you have the congruent agreement of all parties to this common outcome.

5. Break the outcome down to identify areas of most and least agreement.

6. Starting with the easiest areas, move to agreement using these trouble-shooting techniques:

Backtrack as agreement is reached in each area, and finish with the most difficult area.

C) Closing the negotiation:

1. Backtrack frame.

2. Test agreement and test congruence.

3. Future pace.

4. Write agreement down. All participants have a signed copy.

Answers: 1. Tea and coffee—Beverages. 2. Yams and coffee—Cash crops. 3. Clinic and coffee—Six-letter words beginning with “c”. 4. Amphetamines and coffee—Stimulants. 5. Ignatia and coffee—Diuretics.