The first NLP models came from psychotherapy. However NLP is not restricted to psychotherapy, it was simply by historical accident that John and Richard had access to exceptional performers in the domain of psychotherapy when they began modeling. Structure of Magic 1 explored how we can limit our world by the way we use language, and how to use the Meta Model to break free of these limitations. The Structure of Magic 2 developed the theme of representational systems and family therapy. From this basis, NLP has created many powerful psychotherapy techniques, and this chapter will deal with three of the main ones: the phobia cure, the swish pattern, and internal negotiation. It will also give some guide as to where they are best used.

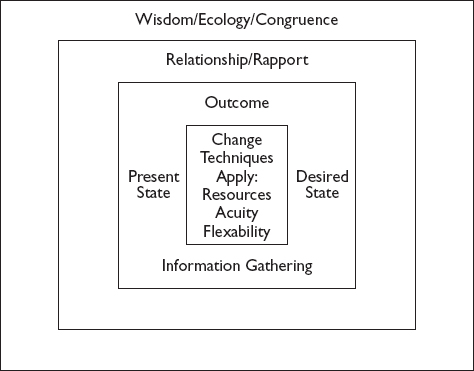

The overall frame around all such techniques is to use them with wisdom, appreciating the person's external relationships and internal balance. The intention of NLP is always to give more choices, never to take them away.

There are two essential aspects for any therapist, or anyone who is helping another person make changes in their life. The first is relationship. Build and maintain rapport to establish an atmosphere of trust. The second is congruence. You need to be completely congruent about what you do to help the other person; incongruence on your part will give mixed messages, and reduce the effectiveness of the change process. This means that you need to act congruently as if you believe the techniques will work. Relationship and congruence are at a higher logical level than any technique that you can apply within them. Use the outcome frame to gather information about the present state, the desired state, and the resources needed to move from one to the other. Within this outcome frame, be sensitive to what you are seeing, hearing and feeling, and willing to respond to the person's changing concerns. Only inside all these frames do you apply a technique. The techniques are fixed means. Be prepared to very them or abandon them and use others to achieve the outcome.

Here is one way to think about where to apply these techniques. The simplest case would be where you want a single outcome: a different state or response in a given situation. This is called a first order change. For example, you may find yourself always getting angry with a particular person, or always feeling uncomfortable dealing with someone at work. Stage fright would be another example where public speaking or performing “makes” you feel nervous and inadequate.

Simple reframes are a good way to start to change this sort of situation, discovering when this response would be useful, and what else it could mean. Anchoring techniques are also suitable here. Collapsing, stacking, or chaining anchors will bring over resources from other contexts. The original behavior or state was anchored, so you are using the same process to change the stuck state as was used to create it. The New Behavior Generator and mental rehearsal also work well if you need a new skill or behavior. changing concerns. Only inside all these frames do you apply a technique. The techniques are fixed means. Be prepared to vary them or abandon them and use others to achieve the outcome.

Sometimes these anchoring techniques will not work because a person has an overwhelming response to an object or situation. Past events can make it difficult to change direction in the present. Change Personal History may not work because there are traumatic past experiences that are difficult even to think about without feeling bad. These may have created a phobia, where an object or situation generates instant panic because they are associated with the past trauma. Phobias can vary enormously: fear of spiders, fear of flying, fear of open spaces. Whatever the cause, the response is overwhelming anxiety. Phobias can take years to cure by conventional methods; NLP has a technique that can cure phobias in one session. It is sometimes known as Visual/Kinesthetic (or V/K) dissociation. Remember to reread the cautionary note on page 55 before practising these techniques.

You can only feel in the present moment. Any bad feeling from an unpleasant memory must come from the way you are remembering it. You felt bad back then. Once is enough.

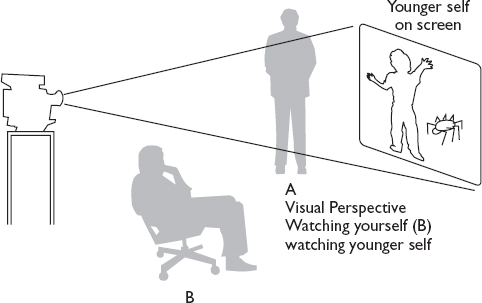

The easiest way to re-experience the bad feelings of a past event is to remember it as an associated picture. You must be there, seeing what there was to see through your own eyes and feeling it again. Thinking back on a memory in a dissociated way by looking at yourself in the situation reduces the feeling in the present.

This is the crucial fact that allows you to erase the bad feelings associated with past events (what an apt phrase that is), so you can simply look back at them in perspective. If you want to work with a phobia or a very unpleasant memory of your own, it is best to have a friend or colleague guide you through these steps. Another person will give you invaluable support when you are dealing with difficult personal issues. The technique is described from the point of view of the guide or therapist.

This takes time and your exquisite attention. Be creative and flexible to help the client within the basic process. You need to be precise with your language as you guide the client through the experience, speaking to him, here, now, watching himself, there, watching his younger self in the picture, back then. If at any time the client falls back into the feeling, come back to the here and now, re-establish the comfort anchor and start again. (Only if the client wishes, of course.) Yo may need to reassure the client by saying something like, “You are safe, here, pretending to watch a movie”. This stage is complete when the client has watched it all the way through in comfort.

In a way phobias are quite an achievement; a strong, dependable response based on just one experience. People never forget to have the phobic response. The closest to having a “good phobia” seems to be “love at first sight”. It would be nice to give ourselves and others good phobias. How is it that someone can learn to be consistently and dependably frightened of spiders and yet not learn in the same dependable consistent way to feel good at the sight of a loved person's face?

Marriages can and do break up because one or both of the partners does an unconscious “phobia cure” on their good feelings, dissociating from the good times, and associating with the bad.

The swish pattern is a powerful technique that uses critical submodality changes. It works on a specific behavior you would rather be without, or responses you would rather not make. It is a good technique to use on unwanted habits. The swish pattern changes a problem state or behavior by going in a new direction. It does not simply replace the behavior, but produces a generative change.

There must always be a definite and specific cue that triggers the response. If the cue is internal, generated from your thoughts, make it an image exactly as you experience it. If it is an external cue, picture it exactly as it happens: as an associated picture. For example, the cue for nail biting might be a picture of your hand approaching your mouth. (The swish is easiest with visual images, although it is possible to do it with auditory or kinesthetic cues by working with auditory or kinesthetic submodalities.)

Break state by thinking of something different for a moment before continuing.

Check that the new self-image is ecological, and fits into your personality, environment, and relationships. You may need to make some adjustments as you try it on.

Think about the resources this self-image would have. It will need resources to deal with the intention of the old behavior. Make sure the image is balanced, believable, and not closely tied to any particular situation. Also be sure that the image is compelling enough that it produces a marked shift to a more positive state.

Now break state and think of something different.

Brains work fast. Have you ever had the experience of describing a process to someone, and feeling that she was doing it as you described it? You are right. She was. (Think of your front door . . . but not just yet!)

Clear the screen briefly after each swish by seeing something different. A “reverse swish” will just cancel the positive swish. Make sure it is a one-way ticket. If it does not work after five repeats, do not keep doing something that does not work. Be creative. The critical submodalities may need to be adjusted, or perhaps the desired self-image is not compelling enough. The process works. Who in their right mind would keep a problem behavior in the face of a set of such alluring, new capabilities?

Second order change is when there are multiple outcomes and secondary considerations involved. All therapy probably involves second order change, as the new resource or response will need to be supported by some growth and rebalancing in the rest of the personality. First order change is where this takes care of itself, or is slight enough to be ignored.

Second order change is best used to describe what is needed where the secondary outcomes are strong enough to block the main desired outcome. Six step reframing is a good technique for dealing with secondary outcomes.

If there are different ideas in conflict, negotiation skills can be used between the different parts of our personality. Resolving a problem involves achieving a balance in the present that is at least as powerful as the old one.

Because balance is dynamic and not static, conflicts are bound to develop between different parts of our personality that embody different values, beliefs and capabilities. You may want incompatible experiences. There may be familiar situations when you are interrupted by another part with conflicting demands. Yet if you yield to that, the first part makes you feel bad. The upshot is often that you enjoy neither activity. When you are relaxing, another part will conjure up vivid visions of all the work you should be doing. If you work, all you want to do is relax. If this sort of conflict is familiar and spoiling both activities, it is time for a truce.

During this negotiation other parts may surface. The deeper the conflict, the more likely that this will happen. All may need to join the negotiation. Virginia Satir used to arrange “Parts Parties” where different people would enact the different parts of the client, who would direct the unfolding drama.

Parts negotiation is a powerful means of resolving conflicts on a deep level. You can never banish conflict. Within limits, it is a healthy and necessary preliminary to rebalancing. The richness and wonder of being human comes from diversity, and maturity and happiness from balance and co-operation between the different aspects of yourself.