Chapter XIX - Minnesota Madness

Early May 1932, St Paul

Merrill is back in the dockside drinking club where Bill Meckel got him an associate membership. He asks to see the boss, and gets shown to a side room by a mean-looking doorman. Entering the cigar smoke-filled room, a snappily dressed stocky man rises from a desk which doubles for a card table some nights.

The club-owner and local mobster Mr Dineen greets Merrill, “Ah, Mr Harrison. You’re becoming quite a regular. Enjoying the entertainment? Or have you come to settle your credit account?”

“Well, Mr. Dineen, I might partake later, and I‘ll settle up shortly, but I’ve got a business proposition to discuss.”

“Sit down, Mr Harrison, and call me Jack.”

Merrill reciprocates by inviting the use of first names (although Jack already knew Merrill’s full name; all club members are background-checked after their first night).

“Now Merrill, we don’t need any flyers printed. I get all my work done by an Irishman down the road, and he gets a few favors from the girls. A neat arrangement. See, he does a beautiful business card.”

Jack flashes an extravagant card: Mr. J. Dineen, Estate Developer & Auctioneer. Merrill uneasily pockets the card. “No, it’s not printing business. Um…what would you say if I asked you if you knew anybody who could scare a business associate of mine?”

“Scare, you say? Well I know some scary guys.” Jack lets out a disconcerting chortle. “I get it. Someone not paying their bills on time, or not handing over cash due to you?”

“Spot on. Can you help?” MerrilI lowers his voice, “I just want this fella roughed up a little. Put him off work for a few weeks. He’s a little weed. Then I’ll contact him and let him know that I might know the guys who did it, and that they might call round again.”

“Whoa-oh! I can see why you’re a big shot down in Iowa. You know how to do business properly in these difficult times. Everybody has a bit of spare cash under the mattress. Sometimes it just needs shaking out. Of course, my acquaintances have fees for this kind of service, which I can broker for you.”

Merrill winces at the openness of this subject matter. “How’s that work, then?”

“Well, it’s probably just like your printing brochure. It’s on a rising scale.” Jack explains, “An accidentally sprained arm won’t set you back too much, but a discreetly broken wrist would be better and keep him away from his desk. It’s a bit pricier though.”

“No, no. Oh, my God. A sprain and a bit of bruising would be fine.”

“Okay, Merrill. I got another meeting due. Go and see my accountant by the entrance. He’ll jot down a few details, and take your deposit. I might ‘catch you later,’ as they say.”

With no further words spoken, Merrill is half-lifted from his seat and pushed towards the exit door by a large man who had observed the exchange from the shadows. As a perspiring Merrill bolts through the open door, Jack can be heard chuckling in his smoky den.

Merrill stutters when asking club staff for directions to the accountant’s office. Barmen and waiters silently point fingers towards the hallway. A few moments later, Merrill hands over money through a small hatch in the accountant’s office door in the club foyer. Merrill pulls up his overcoat collar and disappears into the bitterly cold windswept night, scurrying past derelict dock warehouses.

2011, Sligo

Sue has printed off the Minnesota death and birth certificates, which landed in Jed’s email inbox with a notification “ping,“ whilst he was driving back from the shop. Jed parks the jeep on the driveway and starts waving frantically at Sue indoors. Through the large office window, Sue silently mouths the words, “I know. Another suicide.” Her over-exaggerated lip movements dictate that Jed’s lip-reading skills are not tested. He jogs to the front door.

Jed throws his newspaper on to the office table. “You forgot the milk, again, but never mind… look at this—Paul’s birth cert.”

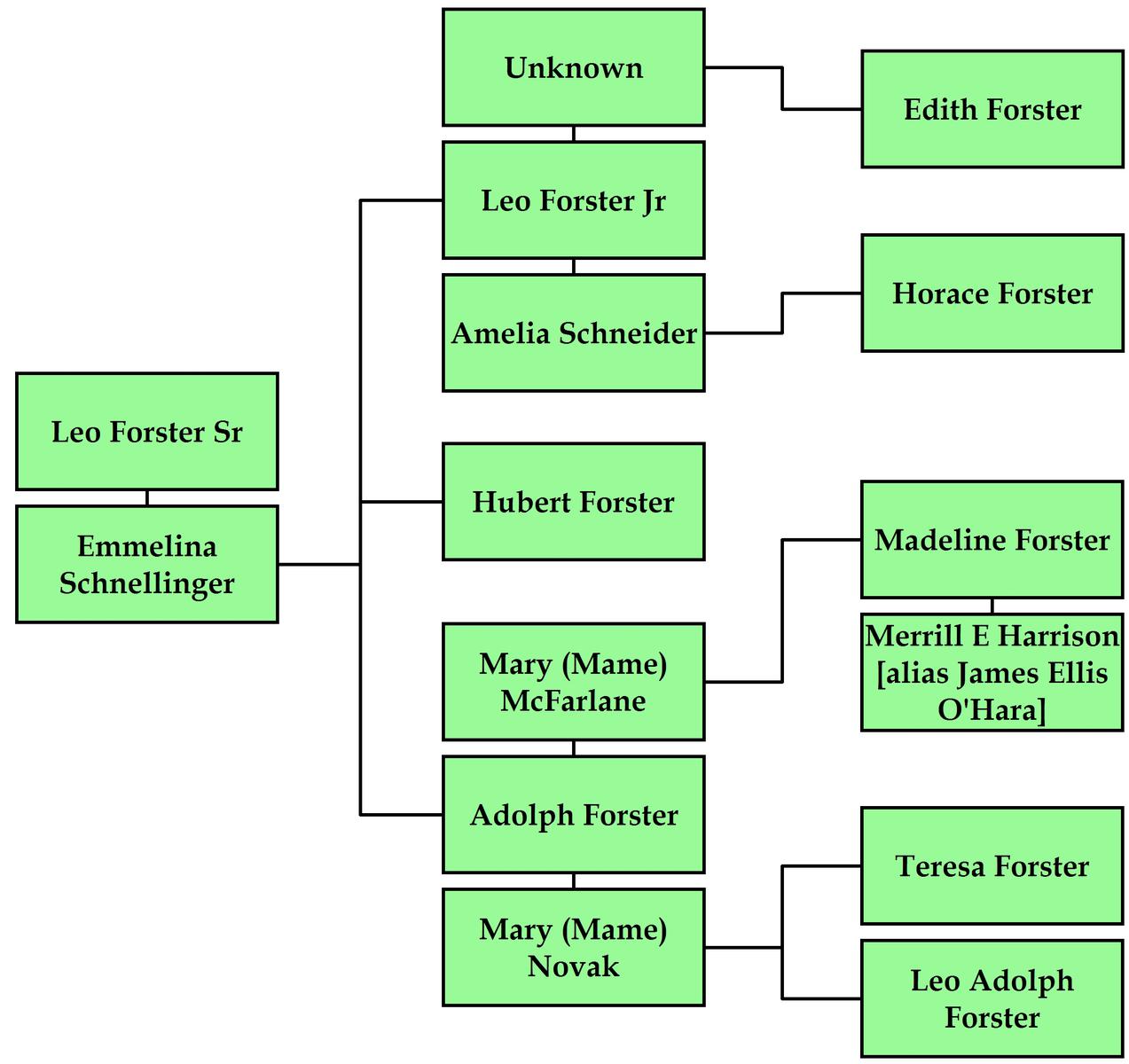

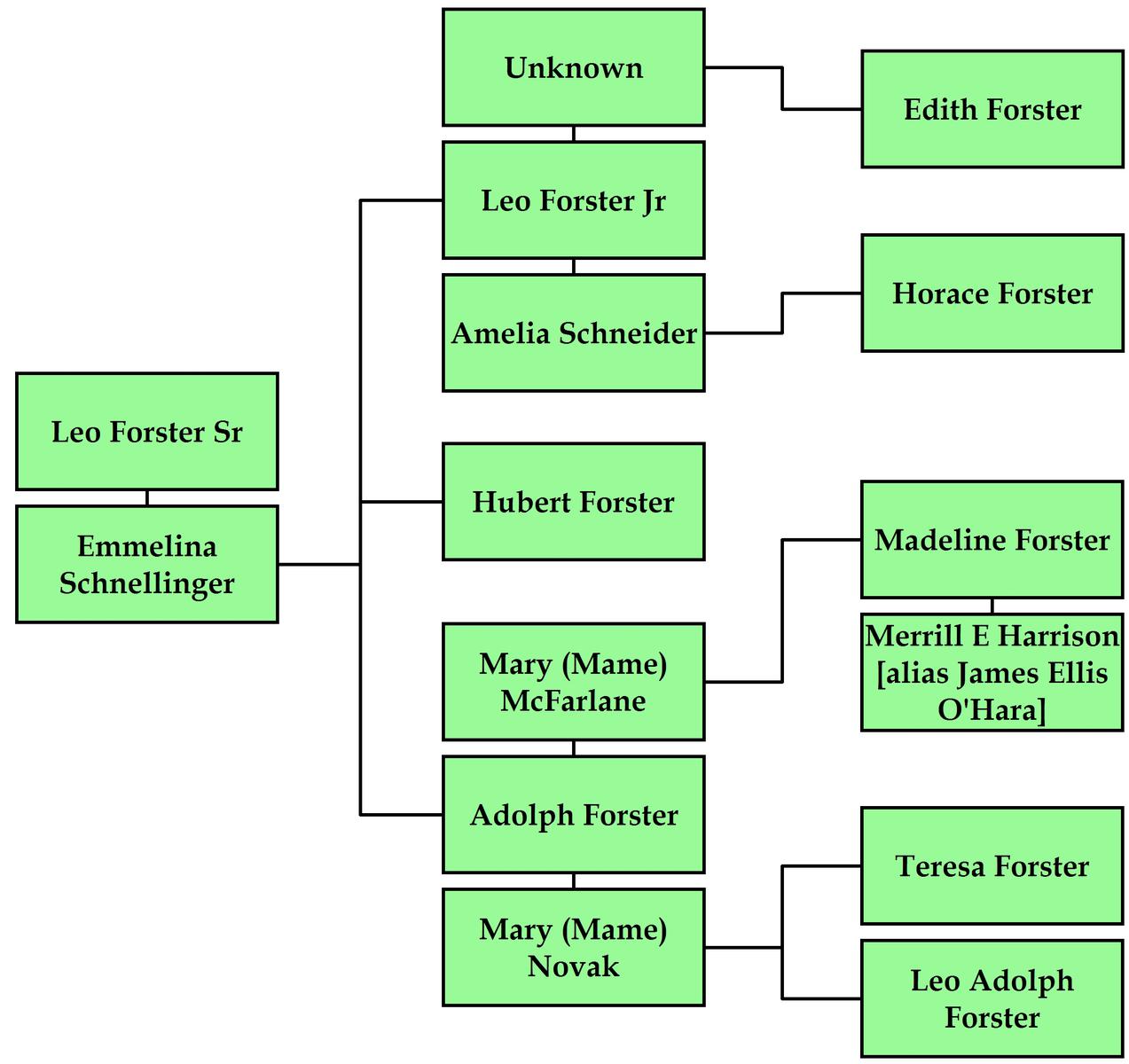

Jed eagerly snatches the still warm copy, and reads aloud, “Father: ‘James Ellis O'Hara of the Hanford Hotel, Mason City.’ Huh?”

“It’s our Merrill, Lover Boy. It’s our bloody Merrill, see! We got his alias!” Sue’s revelation quickly dawns on Jed. Like demented Morris Dancers, Jed and Sue skip around the office throwing exaggerated “high fives“.

Gradually restoring his dignity, Jed goes over to his PC, “But where’s Edith’s hospital record? Oh, here it is. Separate e-mail.” He brings up the document on his image viewer.

“Read it out,” calls Sue, a little breathless from her over-exuberant dancing.

Jed complies: “ ‘Committed to insane asylum: 1907. By whom committed: Self.’ She committed herself. Aw shucks, no scandal there. ‘Parents’: oh, she’s sticking to the story. ‘Leo Senior and Emma.’ ”

Sue states the obvious, “The true story, you mean. Told you. She’s Madeline’s poor insane aunt. Get it into your thick skull.”

Jed suddenly exclaims, “Wait, wait, wait. There’s a second page. ‘Cause of insanity: Worry over the death of a brother. Duration: 3 years.’ So, she got ill in 1904, when Adolph died. Hubert didn’t die until 1911. See — she may have found out about her real parents when Adolph’s will had to be sorted out. All the deceased’s descendants would have had to prove their relationships.”

“Did you have a Guinness when you popped to the village? You seem determined to ignore the facts. Are you a genealogist, or the village idiot?”

Jed continues to read from his computer monitor, “ ‘Condition on admission: Melancholy.’ Runs in the family. Horace was melancholy when he jumped from his office window. Then blah, blah, blah, medical stuff. ‘Paroled,’ nice word: ‘1924.’ So Edith’s back on the scene eight years before Horace got ‘melancholy.’ Perhaps Edith sorted out her own finances after Horace hit the sidewalk.”

Sue corrects this theory, “I wouldn’t think so. In America, once you’re declared insane, you’re always insane. In the courts anyway. She‘d be barred from doing business.”

“Whoa! Scroll back, you silly boy,” Jed admonishes himself. “Here’s a line I skipped: ‘Ancestors insane: No. Blood relation of parents: No.’ NO! What did I tell you! Edith was raised as the daughter of Leo and Emma, but she wasn’t their natural daughter.”

There is an awkward pause in the office dialogue. Eventually, Sue, defeated and crestfallen, asks, “So who’s her real parents?”

“Why, Leo of course. The younger one: Leo Junior. Madeline’s uncle. No wonder Edith’s worried about the death of a brother! She‘s realized that her ‘brother’ is really her dad…and her dad shot his brains out when she was a toddler. Edith probably saw the mess, then later found out who Leo Junior really was—her dad! That would screw anybody up. So, thank you Sue, I’ll have that Guinness right now. There‘s one in the cooler.”

Chapter XX - Echo From The Past

1877, Meriden, MN

Emmelina Forster was comfortable in the back of the compact landau when the pulling horse had been safely steered into a right-hand turn. This manoeuvre was the only real disruption on a long journey south from St. Paul. The excursion had followed the main north-south trail which stretches from Duluth on the Great Lakes all the way down to Kansas City and beyond. However, Emma is not going that far south. Subsequent to the turn-off, the buggy approaches Meriden after a trot covering about eighty miles. Emma is commencing a pre-arranged visit to the remote farm of her brother, Peter Schnellinger. For previous visits, Emma has always used the stage-coach service. Not today.

The horse and buggy pull into the track leading to Peter’s ranch, throwing up dust that can be seen from a distance across flat fields. Alongside the farm sheds, the buggy driver yanks on the reins and shouts, “Whoa!” to the eager horse. A group of excited children, all of different ages, accompany the horse as it walks to the farmhouse path. An older boy exclaims, “Let me take her now, Bert. Good to see you again.”

The chosen chauffeur for the day is seventeen year-old Hubert Forster, the second oldest son of Emma. “Good to see you too, cousin,” replies Hubert as he climbs down from the front bench of the carriage. The ever-polite teenager then guides his mother down from her rear seat. He shows the same courtesy to the final passenger, a younger female acquaintance of Emma’s who will also take a short holiday in the country, away from the city smog. Hubert is to return to St. Paul alone tomorrow, after an overnight rest, to complete his school studies.

The commotion outside of the Schnellinger house has attracted farmer Peter over from his fields, and his wife Millie also greets the guests. “Come along. Come along. I have prepared two separate small rooms for you. The children are excited about sleeping in the barn this summer,” she says. Peter puts his arm around his sister and leads her up the garden path. Behind him, the Schnellinger boys struggle to carry a large trunk.

Emma had celebrated her twentieth wedding anniversary not long before departing from St. Paul for her vacation in Meriden. She had married her husband, Leo Forster, in a small newly-built Catholic chapel in St. Paul way back in 1857. Leo had only been in the city two short years by the marriage day. Indeed, he had only been in America for thirty months. Leo was a good looking young man, back then, and a very talented tailor. His clothes-making skills had been inherited from and taught by his father in his homeland of Switzerland. Leo was raised in the Swiss lakeside village of Tennwil, near to the town of Wohlen, a place with a reputation for producing the finest tailors in the Alpine regions. He was also a very hard-working and trustworthy man.

Emma’s father, Antony, was delighted when he was introduced to Leo, and even more so when Leo asked him extremely politely for his daughter’s hand in marriage. The Schnellingers were from Fautenbach in the Baden section of Germany, and therefore shared a common native language with Leo Forster. Of course, they all tried their best to master the English tongue of their adopted American nation. Antony Schnellinger had brought his family from Europe to Northern America in the 1840‘s, so his mastery of the local language was far more advanced when he gave his blessing to his daughter’s wedding plans.

Antony had declared, “Leo, we were good neighbors in Europe, and now you are welcomed into my family as if you are my own son.”

It took Leo a little while to realize that the first part of Antony’s approval speech referred to the fact that he and his fiancée had grown up in different countries but that their birthplaces were only one hundred miles apart. After emigrating to the U.S.A., most Europeans were bewildered by the size of the place. Many separate American states were bigger than individual European countries. It felt bizarre to be in a new homeland where everyone spoke the same language across thousands of miles of territory. Back in mainland Europe, some neighbors struggled to trade with each other because they could not communicate in a common tongue. This hindered development, and led to many wars.

Antony had no particular skills to speak of when he landed on American soil as a widower with a young family. He knew how to rear farm stock and grow grain, and that was about the limits of his talents. It had been an arduous but necessary sea-crossing, and the continuing journey westwards to the uncultivated grasslands of America had been equally difficult and dangerous. The poverty-stricken German immigrants had first settled in Wisconsin, and labored day and night for much longer-established American pioneers. Antony’s dream was to find and buy his own farmland. That was why he had uprooted his family in the first place.

Minnesota offered richer pickings to enable him to complete his destiny, so the nomadic Schnellingers headed westwards again. Land was on offer, and generous grants were the lure, but on arrival in each county they came across tales of displaced native Indians venting their anger on the invaders from far-off Europe. It was unsafe to stay in one place for too long knowing that local tribes were gathering information in the wilderness, ready for the next bloodthirsty massacre. Revenge was not sweet from Antony’s viewpoint.

The family drifted south to the security of the expanding city of St Paul. They found peace on the outskirts of the citadel. But Antony was getting old, and he handed the baton of family leadership to his remaining unmarried son, Peter—the only son who retained a love of farming as opposed to urban laboring. Peter was sent off to find the elusive Schnellinger dream ranch, and within twelve months and after much toil, he had returned with the deeds to a vacant property in Meriden; half-way to the Iowa state border. Antony’s fifteen year journey was complete.

Before ever setting eyes on his much sought-after Meriden farmstead, Antony had acted as the proud witness at his only surviving daughter’s wedding in St. Paul. Emma was safe with Leo Forster. She had done well to catch the eye of an up and coming city merchant. After the marriage, Leo expanded his business, employing other young Germanic immigrants in his tailoring business. Emma was set up with the management of a boarding house to provide accommodation for the Europeans flooding into St. Paul. Everything was rosy in the marital home for the first five years. Leo and Emma were blessed with three children: Leo Junior., Hubert, and then Emma’s little treasure, Amelia. However, faraway, American politics were becoming divisive.

The brutal national Civil War erupted in the early 1860’s. Leo Senior promptly did his civic duty and enlisted for the Union Army in 1862. Emma feared that she would never see her husband again. Her prayers for his safe return were fulfilled just six months later when Leo arrived home unannounced. He was in one piece physically, but Leo had endured weeks fighting his own battle with ‘The Grippe,’ a virulent strain of influenza. With poor medical attention, he had become a severely weakened man. As a consequence, the Unionists no longer required his services. He would never be quite the same again, and he refused point blank to ever discuss the horrors of his one experience on a noisy battlefield.

Emma illogically blamed the Civil War for the personal desolation wreaked on her own family when peace eventually prevailed nationwide. She was happy each of the three times she hugged her husband and told him that she was pregnant again, but on two occasions it was short-lived happiness. A third son, Schaeffer, fought gamely for over a year as a sickly child, after a troublesome delivery. He succumbed to a fever, and misery engulfed the Forster tailor’s shop and home above.

Adolph, born on New Year’s Day in 1867, was a much stronger child. It seemed that Mr. and Mrs. Forster had overcome their heartbreak. They were very wrong. A fifth son, named Heinz, timed his arrival badly. A deadly virus was creeping around the dirtier streets of St Paul when he made his appearance. He died within days in Emma‘s arms, unable to retain any breast milk. The wretched mother’s agony was complete when, a few weeks later, her beloved seven year-old daughter Amelia was whisked off to a fever hospital after being found semi-conscious in a damp bed. She never returned, and was buried in a mass grave of young St Paul citizens. Emma vowed that she would never put herself through perilous child-bearing again. In Emma’s view, the pain of childbirth was nothing compared to the lingering anguish caused by infant deaths; especially an infant she had taught to eat, walk and talk.

2011, Sligo, Weekend

Sue was surprised to see Jed looking relaxed again. He had been getting so tense since getting hooked into the mystery of Merrill, and the ambiguity of Tim’s maternal ancestors in general. He strolled into the living room with a small wad of printed sheets and interrupted Sue’s viewing of a soppy romantic film on TV. The disturbance irritated her, but she tried not to show it. She put the movie on pause.

“Sue, for a bit of fun, I’ve been seeing how far back in time I can get along the branches of Tim’s family tree. It looks like the Schnellingers win the competition hands down.”

“Call that ‘fun,’ Jed? On a Sunday afternoon! You are becoming a real saddo.”

“And sitting in front of the TV crying is normal, is it?” Jed challenges. “Wipe your eyes and look at this. I came across something which links to Aunt Edith’s illegitimate birth being kept secret for decades.”

Sitting on the arm of the couch, Jed starts to go through all his printed notes with Sue, “You know how the German archivists just have to be the best-organized and most efficient on the planet, like everything else in the modern world which they touch. Well, in no time at all, using the German church record databases, you can get back to an ancestor of Emma’s who was born in 1679. He was called ‘Johannes,’ so Johannes wins the Ancestry World Cup.”

“Is that it? Germany wins the World Cup. What’s new? I thought you said all this connected to Aunt Edith somehow.”

Jed smiles smugly. Sue knows that look. “Look here—in the lineage.” Jed points to a neat chart that simplifies the understanding of the make-up of an ancient German family spanning seven generations down to Emma born in 1833. He explains what he has found out: “This Schnellinger family features in many published pedigrees of German ancestry. So I went through the individual church records of each generation— the baptisms, marriages, burials—just to check that our German genealogist comrades had got it right. I didn’t expect to find one glaring error which the academics had all overlooked.”

“Or should you say robots? All goose-stepping along. One old professor probably wrote the initial pedigree, and everybody else just copied it.” Sue cannot help herself. The English have a long rivalry with the German nation, in sport and in war.

“Probably. But don’t be rude about our European Union partners. Ireland could do with a big loan from the German banks right now.”

“Continue, Herr Neary,” says Sue making an English military salute.

”The big blooper involves Emma’s father, Antony. He was not a Schnellinger at all - just like Emma was not Edith’s mother.” Sue is showing more interest now. Jed keeps going.

“Antony was born in 1801, but his mother Maria Sucher did not marry Andreas Schnellinger until 1802. No-one has ever been able to find a baptism record in the name of Antony Schnellinger, so it was assumed lost, which is not like the German hoarders. But I just did a search for any children born to Maria Sucher before 1802, and up popped Antony. He was christened as Antony Ernst, because his father was George Ernst - but, you’ve guessed it—Maria never married George.”

Sue finishes the tale, having digested the facts and chart in front of her. “So Antony was Maria’s illegitimate child, born in an ultra-Catholic neighborhood. And up stepped Andreas from the Schnellinger household to save her blushes. I see. He married Maria Sucher and adopted baby Antony as his own.”

“You got it. Now then, do you suppose that Antony may have related this tale to his own children? He came from a tiny German community, and must have identified his own true parentage. It’s in the local church register now, and it was on show there two hundred years ago. He was adopted for all the right reasons, and when he went to America, no-one would ever know that he was a frowned upon illegitimate child.”

Sue is fascinated by the connection. “I see where you’re coming from. Perhaps Emma, or even Antony himself, suggested how the respectable Forster family could deal with the embarrassment of Leo Junior getting a local strumpet pregnant. It was the perfect solution all round. The local girl gives birth in secret, and Emma adopts the baby. Leo Junior is off the hook, and Emma gets a little daughter after only delivering sons.”

“Ta-dah!” Jed makes a fanfare noise and then starts singing, “We Are The Champions,” getting up, ready to leave the room.

“But, lover boy, you wasted your time with all that 1679 stuff. Old Johannes was no bloodline relation of Antony or Emma or Adolph and so on. So he’s not Tim’s ancestor. Ha, ha!”

Jed turns back. “Sod off. Get back to your movie. And at the same time as numbing your brain, try to think how Emma could appear in St. Paul with a new baby, after never showing signs of a pregnancy. Now there’s one for you.”

1877, St Paul

The precise military-like plan worked to perfection. Leo Sr. told concerned churchgoers and fellow town councilors that his wife Emma’s illness was showing no signs of abating. Emma would be staying in the fresher air of Meriden until she made a full recovery. Everyone sympathized with Leo Sr. and offered help in any way they could.

A few weeks later, there was an impromptu party in St. Paul. Leo Sr. had run around the local streets, showing everybody a telegram received that morning from Meriden. Emma had not been ill at all. “She had been pregnant, and never knew. She never got the signs like before. It’s over ten years since Adolph came along. The doctors told her she was barren,” proclaimed Leo Sr.

The celebration party commenced when Leo Sr. added that Emma had given birth to a healthy little girl: “We’re going to call her Edith, in honor of my dear old German mother, Edith. Maybe, my mama sent us this miracle from heaven” All the local ladies were thrilled. They knew that Emma had always wanted a girl. Edith was indeed considered to be a blessing from God for a decent family. A thanksgiving mass was arranged at the Catholic church. All the good people of St. Paul prayed that Emma and baby Edith would return safely together to the bosom of their family home.

Not too long after, Leo Junior volunteered to pick up his mother and baby “sister” from Meriden in the Forster’s buggy. The young lady who had escorted Emma to her brother’s farm a few months back was nowhere to be seen. Leo Sr. had discovered that there was a live-in vacancy for a good seamstress in Kansas City. He knew the rival tailor well.

Leo Junior, an exemplary college student, was scheduled to start his working career at the bank in St Paul on Monday. His brothers would later opt to join the burgeoning local rubber manufacturing industry. Ultimately, the Forster family owned every one of the massive rubber factories of St. Paul, plus several private properties and other prudent assets.

The horse trotted home northward, and made good time. Leo Junior was on the very same road that a certain Merrill Harrison would traverse with alarming frequency more than fifty years later. Merrill moved fast. He had more horse-power in his days.