![]()

In the spring of 1941, there were two coastal gunboats and five river gunboats assigned to the Asiatic Fleet to operate in various parts of China. These unique ships were symbols of days long past, when their mere presence was enough to command respect for the American flag and to protect American interests. But times had changed, and Japan, having captured most of China’s important cities, was then the arrogant, dominating power. With Japanese shore batteries and shipboard guns literally pointing down their throats, the gunboats stayed in China only because the Japanese, not yet ready to move against the United States, disdainfully tolerated them.

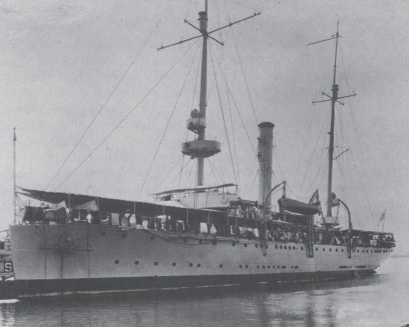

Some months before World War II, Admiral Hart, sniffing the freshening winds of war, ordered the two seagoing gunboats, the Asheville, built in 1918, and the Tulsa, built in 1922, back to Manila. These boats, which had acted for years as station ships in such ports as Swatow, Amoy, Tientsin, and Tsingtao, were 241 feet long and carried a crew of 185 officers and enlisted men. In contrast with the flat-bottomed river gunboats, they had proper hulls and keels. Their main armament consisted of three 4-inch .50-caliber guns, three 3-pounders, and three 1-pounders. The main drawback of these single-screw ships was that they could make no more than 12 knots, which precluded their operating with the faster combatant units of the fleet.

The five river gunboats were assigned to Rear Admiral William A. Glassford, commander of the Yangtze Patrol, who was headquartered in Hankow, China. These lightly armed, flat-bottomed, keelless vessels were built in the late 1920s for service on the shallow rivers of China and were not meant to ply the open seas. Nevertheless, in late November 1941, Hart, convinced that war with Japan was imminent, ordered Glassford, his staff, and all but the two smallest river gunboats—the Wake and the Tutuila—back to Manila.

Because of her position 1,300 miles up the Yangtze River at Chungking, China’s provisional capital, the Tutuila was turned over to the Chinese Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek, and her ship’s company was ordered back to the United States for reassignment. That company, which had been reduced to two officers and twenty-two enlisted men, had an arduous journey home: they departed Chungking via CNAT (the Sino-American airline) to Calcutta, traveled across India by train to Bombay, and from there went by ship around the Cape of Good Hope to Trinidad, whence the final leg of the journey was made by aircraft—an odyssey of more than 11,500 miles.

The only escape route open to the crew of the Wake, which was stationed 600 miles up the Yangtze River at the Japanese-held city of Hankow, was by way of Shanghai, where they could join up with the larger gunboats Luzon and Oahu (PR-6). Ignoring bellicose Japanese demands that he stay, the Wake’s skipper Lieutenant Commander Andrew E. Harris, got his ship under way during the early afternoon of 24 November 1941. To make the departure date of the other gunboats, the Wake had to be pushed as fast as her ancient boilers would permit, and Harris was not about to let the Japanese stop him.

The fifth river gunboat, the Mindanao (PR-8), which was stationed in Hong Kong, was to steam to Manila unescorted.

On the afternoon of 28 November, the Wake arrived in Shanghai, where the Luzon and Oahu, their main-deck doors and windows covered with watertight steel shutters, and fireroom blower intakes protected by cofferdams, were making ready to put to sea at midnight. Considered not seaworthy enough to make the trip to Manila, the Wake, manned by several of her crew augmented by local naval reservists for a total of fourteen, was left at Shanghai. Her new commanding officer was a naval reservist, Lieutenant Commander Columbus D. Smith. The rest of the Wake’s company found berths in the other gunboats. Eight of the fourteen men left with the Wake were radiomen who were to maintain the consulate’s communications and operate Smith’s short-wave radio equipment ashore. Unfortunately, the day war began, the Wake fell easy prey to the Japanese, and her crew, along with other navy men in Shanghai, became prisoners of war.

Shortly after midnight on 29 November, the Luzon, with Glassford on board, got under way, followed by the Oahu. At dawn they were safely past the Yangtze fairway buoys, heading south in the China Sea at about 10.5 knots. To express his concern about the river-oriented ships’ ability to make the trip, Glassford sent the following dispatch to Hart: “Shall make effort to run straight Manila inside Pescadores arriving if all goes well about 4 or 5 December. Should war conditions render necessary shall follow coast await opportunity final leg Manila-ward. If unable make Manila propose make for Hong Kong in hostile emergency.”

As luck would have it, a typhoon was making up in the Formosa Strait. Hart, gravely concerned for the safety of the river gunboats in a treacherous ocean, sent the minesweeper Finch (AM-9) and the submarine rescue vessel Pigeon to tow them if necessary, or to take off their crews. It was not long, however, before these tough, little seagoing ships were themselves in trouble. In heavy seas, the Pigeon’s rudder was damaged, making her unable to steer, and one of her two anchors was carried away. The Finch, having lost both her anchors, was towing the Pigeon toward the lee of Formosa, where repairs could be attempted.

In the meantime, the flat-bottomed river gunboats were having a terrible time of it. Pounded by mountainous seas, lashed by howling winds, and drenched by blinding rain squalls, they labored along. At one point, the Oahu’s inclinometer recorded an astounding, near-fatal roll of 56 degrees to starboard. The terrifying experiences of those on board the gunboats during that wild voyage defy description, but Admiral Glassford gives an inkling of their ordeal:

The 2nd and 3rd of December will never be forgotten in all their grim details. Not only were we harassed by sweeps of Japanese aircraft overhead and by insolent men-of-war ordering us to do all manner of things that we could and would not do, but as we approached the Straits of Formosa and later got well into it, we experienced a heavy, choppy sea which was almost the undoing of the personnel if not the little craft themselves. We were tossed about as by a juggler, now up like a shot to a crest from which we would fall like a stone. The ships were rolling 28 to 30 degrees on a side, with a three-second period. They were taking green seas over the forecastle and even more dangerous, surging seas over the stern.

Speed had been reduced to little more than steerage way, but even so the engines raced violently, the ships shaking and trembling.

What disturbed us most was whether or not the human beings on board would be worthy of these incredibly stout little ships. For nearly 48 hours there was experienced the hardest beatings of our lives at sea. There was no sleep, no hot food, and one could scarcely even sit down without being tossed about by the relentless rapidity of the lunging jerks. The very worst of all the trip was after clearing Formosa, with a quartering sea. I recall just before dawn on the 4th of December, while clinging to the weather rail of the bridge deck, that our situation could not possibly be worse and wondering just how much longer we could stand it. Not the ships, which had proven their worth, but ourselves.*

Dawn of 5 December brought a cloudless sky, a placid sea, and blessed relief to the exhausted men on board the storm-racked ships. Like a horse heading for the barn, the Luzon moved out for Manila at 16 knots, outdistancing the slower Oahu. The Pigeon and Finch, following many miles astern, were slowly but surely beating their way to Manila. That same day, Glassford, the last commander of the Yangtze Patrol, hauled down his flag and announced, “ComYangPat dissolved.” To “China hands” who had experienced the mysteries of the Orient and basked in its luxury since the patrol was formally established twenty-two years earlier, and eighty-seven years after the first American warship groped her cautious way up the murky waters of the Yangtze River, it signaled a sad end to “one hell of a fine duty station.”

Following the bombing of the Cavite Navy Yard on 10 December 1941, the coastal gunboats Tulsa and Asheville, in company with the minesweepers Lark and Whippoorwill, sailed south from Manila for the Netherlands East Indies. Until the day Java fell, these gunboats operated as harbor-entrance patrol vessels, mainly at Surabaja and Tjilatjap. When the Japanese landed on Java, they departed independently from Tjilatjap bound for sanctuary in Australia. The Tulsa made it but, on 3 March 1942, the Asheville, like other Allied ships fleeing for their lives, fell victim to Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s big carrier task force, and was sunk somewhere off the southeast coast of Java. Only one of her company, Fred Lewis Brown, is known to have been picked up, and he died in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp at Makasar in the spring of 1945.

The last of the river gunboats to reach Manila was the Mindanao, from Hong Kong. She, too, experienced difficult times at sea, having been forced to tack 180 miles up the China coast to Swatow before being able to head down to Manila. When she arrived on 10 December, the crews of the three river gunboats, at home in the confined waters of Manila Bay, were ready to join the fight for the Philippines.

The Mindanao was a shade more than 210 feet in length and had a ship’s company of 65 officers and men. Upon arrival in Manila, her two ancient saluting guns were replaced by two .50-caliber machine guns, which augmented her two 3-inch guns and her twelve .30-caliber Lewis and twelve .30-caliber Browning machine guns. Her sister ship Luzon was similarly armed, but had no Brownings. The Oahu was about 191 feet in length with a ship’s company of 52 officers and men. She was armed with two 3-inch guns and twelve .30-caliber Lewis machine guns.

The coastal gunboat USS Asheville (PG–21), sunk 3 March 1942 in the Indian Ocean south of Java by Japanese warships. Only one survivor, Fred Lewis Brown, was rescued; he died in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp at Makasar, Celebes, in the spring of 1945. National Archives, 80–G–461042

At first, the Mindanao was assigned as station ship for Corregidor’s minefield channels. The Luzon and Oahu occasionally patrolled off the minefield entrance, but spent most of their time in Manila Bay, preventing enemy troops from infiltrating behind the lines at night. Because of the acute fuel shortage, however, these patrols had to be discontinued on 27 December.

Japanese planes heavily bombed Corregidor and the nearby anchorages on 29 December. The Mindanao was straddled and slightly damaged. The bombs aimed at the two other gunboats missed their targets, but they landed close enough to throw salt water over the boats’ decks. This close call made Captain Kenneth M. Hoeffel, commander of the Inshore Patrol, aware of the vulnerability of the anchored gunboats, especially since the antiaircraft guns on Corregidor were, in the main, ineffective, and the vessels themselves had nothing with which to fight off high-level bombers. Accordingly, he moved his headquarters from the Mindanao to the navy tunnel on Corregidor and ordered the gunboats’ crews ashore during daylight hours to help strengthen Corredigor’s beach defenses. At night, however, they were permitted to return to their ships, where they could at least enjoy the luxury of sleeping in bunks.

During the month of January, a few night patrols were made, but by 15 February, there was too little fuel oil to permit any routine patrols. What oil was left was split between the Mindanao and the Luzon for use only in an emergency. Such an emergency arose on the night of 6 April. According to intelligence reports, the Japanese had assembled some small boats and were preparing to infiltrate behind the lines on Bataan. The Mindanao and Luzon were ordered to forestall this maneuver. For nearly seven hours they searched Manila Bay east of Bataan, but found nothing. At about 0200, however, silhouetted against a moonlit sky, they sighted eleven small craft heading for Bataan. The gunboats opened fire, but clouds suddenly blotted out the moon and enshrouded the enemy in darkness. The Mindanao immediately fired star shells to illuminate the targets, and both vessels again opened fire. Japanese shore batteries, alerted by the gun blasts, quickly zeroed in on the gunboats and heavy shells began falling uncomfortably close. The troop-laden Japanese boats beat a hasty retreat, but not before four of their jury-rigged invasion fleet had been sunk and several others badly shot-up. The Mindanao and Luzon then withdrew, ending what might be called the Battle of Manila Bay—gunboat style.

The bloody fighting on Bataan ended on 9 April 1942, and the bomb-battered defenders of Corregidor, all too aware that the worst was yet to come, prepared for the fight of their lives. While the abandoned river gunboats swung silently around their hooks in Corregidor’s south harbor, like tethered lambs waiting for the howling wolves to descend upon them, their crews were getting ready to play a new role in the grim game of war. No longer sailors armed with 3-inch guns, they had become artillerymen assigned to guns the likes of which most of them had never seen before.

The crew of the Mindanao was ordered to Fort Hughes, on Caballo Island, and put in charge of Battery Craighill’s four, huge 12-inch mortars of 1912 vintage. Hastily indoctrinated by several veteran artillerymen, the sailors fired twenty-six rounds at Japanese positions on Bataan and were adjudged qualified. Crewmen of the other ships were given the same perfunctory check-out. Those of the Luzon were assigned to Battery Gillespie, which consisted of two, mammoth 14-inch disappearing guns, and those of the Oahu took over a battery of 155-mm. howitzers.

River gunboat Luzon (PR-7) of the Yangtze Patrol. Naval Institute Collection

The inevitable end was fast approaching. On 2 May, the Mindanao, seriously damaged by bombs, was permitted to sink in order to ensure that the Japanese would never enjoy her services. The Luzon, salvaged by the Japanese, served the enemy until American aircraft sank her irretrievably in 1945. The Oahu, pounded by heavy artillery shells, could take no more punishment and, on 6 May, the last day Old Glory flew over the “rock,” she went to her watery grave off the bloody beaches of Corregidor.

The hardened veterans of the Yangtze Patrol acquitted themelves as one would expect—with honor and courage beyond the call of duty. Eagerly, they accepted the role of artillerymen and manned their guns until they were either knocked out or could no longer bear on the enemy. Three of Battery Craighill’s four 12-inch mortars were silenced by Japanese artillery, but the fourth continued to fire on the invaders until silenced by the order to surrender.

Although the Inshore Patrol was structured mainly around the three river gunboats, two other vessels, the tug Napa (AT-32) and the 83-foot, two-masted schooner Lanikai, were also assigned to it. The Napa was scuttled when Bataan fell, but the Lanikai, commanded by Lieutenant Kemp Tolley, departed Manila Bay on 26 December bound for Surabaja. The seas through which she traveled were dominated by enemy warships, yet, the little schooner and her intrepid crew arrived safely and, with the fall of Java, once again eluded the Japanese to gain sanctuary in Australia.

Another ship, the Isabel, sometimes classified as a gunboat and sometimes as a yacht, should be mentioned here. Although not designated a unit of the Inshore Patrol or of any other operating segment of the Asiatic Fleet, she, some years before, had served as flagship for the commander of the Yangtze Patrol. When she ceased to play that role, she remained under the operational control of the commander in chief, Asiatic Fleet, and was based in Manila.

Because she was old, in poor condition, and ill-equipped for combat, the Isabel was considered expendable. For that reason, on 3 December 1941, she was sent on what could have been a suicidal mission which had been personally ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. With her four aged 4-inch deck guns hidden so that she would look like an innocent merchantman, the Isabel was directed to spy on a heavy concentration of Japanese transports and warships gathered in Camranh Bay, Indochina, even though the concentration was already being monitored by aircraft of Patrol Wing 10. The Isabel came within sight of the coast of Indochina, but was recalled just in time to be off Manila Bay when war with Japan broke out.

Sent to the Netherlands East Indies soon thereafter, the Isabel was assigned strange and dangerous missions. In that she generally operated alone and under various commands, including Dutch, her noteworthy accomplishments, among them the sinking of a Japanese submarine and the rescue of survivors from a torpedoed merchantman, went unnoticed. In fact, there were times when, in the confusion engendered by the unstoppable Japanese onslaught, her very existence was overlooked by the U.S. Navy.

Clearing the minefields at 2200 on 1 March 1942, the Isabel was the last U.S. Navy ship to leave Tjilatjap. Taking with her twenty-one late arrivals from Admiral Glassford’s staff, she eluded Japanese warships and aircraft, weathered a typhoon in the Indian Ocean, and arrived, somewhat the worse for wear but safe, in southern Australia.

*Glassford, “Narrative of Events,” pp. 30–33.