![]()

On 21 December 1941, the submarine Stingray sounded the alarm. A massive Japanese invasion force, under cover of fighter planes, was landing on the shores of Lingayen Gulf, midway up the west coast of Luzon. From the very beginning of the war, a landing in that area, about 100 miles from Manila, had been anticipated. However, Japanese dominance of the skies over the Philippines having driven the PBY seaplanes of the Asiatic Fleet’s Patrol Wing 10 south to the Malay barrier and destroyed the army’s Far East Air Force, any hope of air reconnaissance had been eliminated. For this reason and because the submarine S-36, detailed to patrol the area, was having trouble with her radio transmitter and had to be recalled, the Japanese were able to hit the beach unmolested.

Had this enemy force of about eighty ships, which included cruisers and destroyers, been detected earlier, a strong pack of American submarines could have been mustered to intercept and harass it en route. But, with its faulty torpedoes, how much effect such a pack would have had on the first Japanese landing in force on Luzon is a matter of conjecture.

The Stingray did not arrive on the scene until after the enemy ships were safe within the confines of the gulf. Nevertheless, in a last-ditch effort to attack, the submarines S-38, S-40, Saury, and Salmon were rushed to the Lingayen area to join the Stingray.

It was practically impossible to attack the invasion fleet because, although the mouth of the gulf is some 25 miles wide, treacherous reefs protect almost half of it and numerous destroyers and patrol boats were guarding the rest. More than that, the overall shallowness of the gulf and its poorly charted depths made submarine operations extremely dangerous. A foray into it by the three big fleet-type boats would have been suicidal. Consequently, four of the submarines lay off the entrance to attack the only targets available—Japanese destroyers, while the fifth, the little S-38, commanded by Lieutenant Wreford G. “Moon” Chapple, entered the gulf.

“Moon” Chapple, a heavyweight boxing champion at the U.S. Naval Academy, was well aware of the dangers confronting him in Lingayen Gulf, but he was determined to get a crack at the enemy. His best hope of entering the gulf undetected lay in going through the area the Japanese believed no submarine would dare to venture—over the reefs. If the S-38 was caught on the surface in waters too shallow for her to dive, it would be the end for her. Nevertheless, Chapple and his gung-ho crew decided to take the risk.

In the dark, early hours of 22 December 1941, Chapple, ably assisted by his navigator, Lieutenant (jg) Robert C. Fletcher, commenced working the S-38 over the reefs. For three and a half tension-packed hours they cautiously maneuvered the boat through the perilous area and, just before dawn, she submerged in the no-less-dangerous waters of Lingayen Gulf.

Then at 0615, Chapple brought her up to periscope depth and, as the first rays of sunlight shattered the night, he surveyed the situation. He did not mask his delight at what he saw. The entire east side of the gulf was alive with Japanese ships. Unconcerned that two destroyers and numerous patrol boats armed with depth charges were patrolling like fierce watchdogs near the transports, Chapple slowly, ever so silently, inched his boat closer to his targets. It took him close to an hour to get into firing position, and all the while tension mounted as the crew, eager to score a kill, prayed they would get there without being detected. At last the moment of truth arrived. Chapple selected four fat targets and fired four torpedoes.

Seconds ticked by and, as the time for impact came and went, Chapple and his men looked at each other in shocked disbelief. How could it be? All four torpeodes had missed. Now, instead of the sound of torpedoes striking home and the noises of sinking ships breaking up, there was the ominous pounding of a destroyer’s propellers racing every closer as she traced tell-tale torpedo wakes to their source.

Chapple dove the S-38 as deep as he dared and headed east to escape the destroyer, whose exploding depth charges reverberated throughout the submarine and sounded somewhat like a boiler being pounded with a sledgehammer. With luck and canny maneuvering on his side, it took him only forty-five minutes to outwit the kill-bent destroyer and, while depth charges ripped up a far-removed area of the gulf, the S-38 was stalking other prey.

To Chapple and his crew it seemed incredible that all four of their torpedoes could have missed. The range was easy, the targets were moving slowly. In all respects, the circumstances were ideal. What none of them knew or suspected was that their Mark-10 torpedoes ran several feet deeper than set. Believing he had miscalculated the draft of the targets, Chapple set his remaining “tin fish” to run at a depth of 9 feet instead of 12.

It was 0758. The S-38 was within easy range of an enemy transport at anchor. Through the periscope, as he made ready to fire, Chapple could see enemy troops massed on the decks ready to disembark. In quick succession he fired two torpedoes. The first ran ahead of the target, but the second ran true. Fascinated, Chapple watched panic-stricken Japanese soldiers pointing to the approaching torpedo. All at once, a violent explosion jarred the S-38, as the 5,445-ton transport Mayo Maru blew apart and vanished into a watery grave.

The S-38 spotted two enemy destroyers charging toward her. Chapple ordered a crash dive and had the boat rigged for depth charging. She went down until she hit bottom. In a matter of minutes, all hell broke loose around her as the avenging destroyers unleashed a furious barrage of depth charges. The old S-boat and her crew took a terrible beating as Chapple desperately maneuvered in one direction and another to escape the “pinging” destroyers. This was a dangerous game of blindman’s buff because the submarine, having no sonic depth-finding gear, was forced to grope her way through the gulf’s unknown depths.

All at once, for some mysterious reason, the S-38 slowly began rising toward the surface. Her auxiliary tanks were flooded and she stopped just short of breaking into the clear, with 47 feet showing on her depth gauge. The tanks continued to fill and the submarine sank back to the bottom but, as she coasted forward, her nose plowed into a mud bank and she stopped.

With the waters above teeming with destroyers and patrol boats all dropping depth charges, some nearby, some far away, Chapple did not dare take the risk of giving his position away by making the noise involved in attempting to back out of the mud. He had no alternative but to order all machinery, except the motor generator on the lighting circuits, stopped. Lying silent in the deep, with the sound of depth charges hammering in their ears, all hands wondered to themselves whether they would eventually be able to break free of the mud or whether this was to be their final resting place.

The noise of high-speed propellers—probably destroyers or patrol boats on the hunt—continually approaching and receding could be heard on the sound gear and was so nerve-racking that Chapple ordered the sound man to turn his gear off and stow it. There was not a single thing anyone could do about it and, if they were going to die, what was the use of knowing exactly when?

Chapple called all his officers and chief petty officers together to discuss the situation. They decided that their best chance of survival lay in remaining absolutely silent until moonset, then attempting to break free. Accordingly, the whole crew removed their shoes, spoke in whispers, and were careful not to drop so much as a spoon for fear the give-away sound would be picked up by the enemy overhead.

Almost all day long, they heard depth charges exploding in various parts of the gulf, some too close for comfort. The noise of small boats passing overhead at regular intervals was judged to be caused by landing barges going to and from the beach. When larger ships passed over, the heavy pounding of their propellers reverberated throughout the boat. Their passing nearby caused the S-38, lying in shallow water, to rock back and forth and, when that happened, the sound of water sloshing in the control-room bilges seemed to mock the tomb-like silence in the boat. Chapple, faced with the prospect of many painfully long, anxious hours of waiting, broke out a deck of cards and started a game of cribbage in the control room. He hoped thereby to relieve tension and allay fears that he might be seriously worried about how he was going to get the S-38 free of the mud, which he was.

Having no air-conditioning, the submarine soon became as hot as an oven. Men and machines began to drip and the decks became slimy with sweat and condensed moisture. Humidity thickened to an almost visible fog. From stem to stern, the boat reeked of perspiration, warm oil, and battery gases. Gasping for air, men sprawled on decks or moved like zombies to perform little tasks which suddenly became tedious. Soda lime was sprinkled throughout the boat to absorb carbon dioxide, but it did little to freshen the foul air.

After twelve punishing hours of lying on the bottom, Chapple decided it was dark and safe enough to attempt to surface. Exhausted men, reeling at the end of their physical tethers, manned their stations. Ballast was blown and, when the engines hummed in reverse, the old S-boat shuddered a bit then slowly pulled free. All hands were overjoyed by the ease with which they had come out of the mud but, as she backed, the S-38 took a sudden steep angle down by the stern, and her port propeller hit bottom, knocking it off center. This unhappy turn of events caused the propeller to make a rasping noise as it turned, which jeopardized the submarine’s chances of evading enemy destroyers.

No Japanese ships were in sight, and Chapple took the S-38 to the surface. Hatches were flung open to air the boat and, with this new lease on life, the crew’s flagging spirits were rejuvenated. For two hours the S-38 slowly cruised westward on the surface using one engine for propulsion and the other for charging batteries. Then it happened again. A lookout sighted a destroyer heading their way at high speed. Chapple dove his boat in a hurry and the enemy ship passed without sighting or detecting them. One hour later the S-38 again surfaced to continue charging her batteries. Anchored off Hundred Islands at dawn, Chapple made a stationary dive to remain on the bottom during daylight hours and give his crew a much-needed rest.

The S-boat surfaced at dusk on 23 December, and remained at anchor to complete the charging of her batteries. Once during the night she was forced down by a roving patrol boat which, fortunately, failed to sight her. By 0500 on 24 December, her batteries were fully charged and the S-38, although crippled, was again ready for battle. At 1127, Chapple sighted six large auxiliary-type ships some distance away and maneuvered so that he would be able to get among them when they anchored. Twenty minutes later, when he was at periscope depth and slowly closing in on his targets, a bomb or shallow mine exploded forward of the conning tower. The shock threw crewmen off their feet and knocked out both depth gauges in the control room. Instantly, Chapple dove to 90 feet and headed north, puzzling over the source of the explosion because the only destroyers in sight were several miles away.

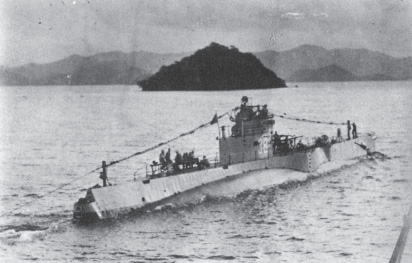

The S-38, one of six S-class submarines assigned to the Asiatic Fleet’s Submarine Squadron 20. Naval Institute Collection

Ten minutes later, the sound man reported one or more destroyers bearing down on them. Chapple stopped all machinery except that to the bow planes, which were used for depth control. At 1205, three depth charges exploded to port. Three minutes later, five more hammered the boat from starboard. At 1223, four more of the devils burst to starboard, followed three minutes later by another.

The S-38 was taking a terrible beating, and the deadly depth charges were coming ever closer. Chapple, fearing that any second might be their last, took a desperate chance to escape and rang up full speed ahead on all motors. With her noisy propeller, the S-38 did not have a snowball’s chance in hell of eluding the Japanese. No sooner were her engines started than four more depth charges exploded to starboard. Instantly, Chapple ordered all engines and machinery stopped, and the S-38 silently sank to the bottom. As she did, eleven more depth charges, in rapid succession, bracketed her. The crew, trapped in the cigar-shaped, iron hull, literally sweated it out and fearfully wondered just how much more punishment their old boat could take. Within a period of forty-eight minutes, twenty-eight depth charges had burst dangerously close to her, but her hull was still intact and her crew, although shaken both physically and mentally, was not about to say die. The Japanese destroyers and patrol boats seemed to have lost track of the submarine, for they could still be heard moving about in other areas.

By 1720, propeller noises had died away and, to the men silently waiting in the stifling heat as they had done the day before, it seemed as though once again they had outfoxed the enemy. No depth charges had been dropped on them for more than four and a half hours. From the control room came the word that all was clear. Just then, six depth charges exploded terrifyingly close, and battered submarine and crew unmercifully.

There having been no sound of propellers overhead for several hours, the S-38 assumed that the Japanese, believing they had finished her off during their earlier massed attacks, had left a patrol boat anchored in the area to listen for signs of life. Hearing none, that boat dropped these depth charges for good measure as she secured for the night. A present from Santa Claus that Christmas Eve was nowhere in evidence. In fact, it was probably the most depressing Christmas Eve any of the men on board the S-38 were ever likely to experience. At 2230, while the boat was submerged and running slowly on the west side of the gulf, there was an abrupt jolt, which all hands knew only too well meant they were aground.

The submarine was worked clear and Chapple, finding no Japanese in sight, surfaced near Hundred Islands, but the submarine’s troubles were far from over. When she was riding high, Chapple gave the order to ventilate the hull outboard and the battery room into the engine room. No sooner had this started than there was an explosion in the after battery room. Chapple, who was on the bridge, raced below to find thick smoke pouring from the after battery compartment and yellow flames quivering in its gloomy interior. Two men had bad burns and a third, Chief Machinist’s Mate E. C. Harbin, a broken back. Electrician’s Mate Third Class Howard L. Buck, Chief Machinist’s Mate Ross, and Chapple, quickly donned rubber boots and raincoats and went into the compartment to fight the fires and remove the injured men.

The explosion, thought to have been triggered by a spark when someone started the blowers before air had time to circulate and freshen the gaseous atmosphere, cracked several battery cells. As soon as the fires had been extinguished, electricians went to work to cut the damaged cells out of the circuit. By dawn of the twenty-fifth that work had been completed, but the S-38 had lost half of her submerged power. That loss, coupled with her damaged propeller, was going to make it exceedingly difficult for her to evade enemy destroyers. During the night, however, a happy note had been struck: a radio message ordered the S-38 to leave the gulf and return to base.

With daylight breaking and Chapple about to submerge, it was discovered that some of the gaskets on the engine-room hatch, which had been opened to air the boat, had rotted and the hatch would not close tight. While the hatch was being dogged down, a Japanese destroyer squadron came into view, heading their way. With speed spawned of desperation, the hatch was secured just in time for the S-38 to crash dive before she was sighted.

Not long after the destroyer menace was over, a pesky patrol boat picked up the sound of the S-38’s defective propeller, and once again she became the target of deadly “ash cans.” Chapple managed to avoid them and threw the enemy off his track by taking his boat deep but, for the third time, she ran aground. This time she was hung up on a mud bank with her bow angled 50 feet higher than her stern. Although it was very hazardous to move along the slippery, tilted decks to operate controls, every effort was made to break the submarine free. However, the slimy mud, with the suction of a giant octupus, seemed reluctant to relinquish its victim. After what to the men was an eternity of frustrating work, the S-boat slowly began sliding backwards.

Jubilant smiles of relief soon turned to brows furrowed in anguished disbelief. As though the crew of the S-38 had not been through enough hell for a lifetime, the old boat began to slip faster and faster down into the depths. With electrical power reduced by the battery casualty, it was impossible to stop the downward movement. When pressure gauges indicated that the boat was at 300 feet, 100 feet below her tested depth, and she was showing no signs of leveling off, all hands feared that the tremendous pressure to which she was being subjected would crush her like an eggshell. At 325 feet, her ballast tanks compressed, causing the battery-room decks to buckle, a terrifying signal that the end was near. At 350 feet, her steel plates groaning under the intense pressure and threatening imminent collapse, her downward movement suddenly stopped and she headed back up.

With her new-found buoyancy, the S-38 moved ever faster toward the surface. Chapple did everything in his power to level off at periscope depth, but he could not stop her and, to the consternation of all on board, she broke the surface like a harpooned whale. He knew that, had this action been spotted by the enemy, every destroyer and patrol boat in the gulf would soon be on top of them, and he doubted his crippled boat’s ability to survive much more depth-charging. A 360-degree periscope sweep of the gulf disclosed that, miraculously, there was not an enemy ship in sight. This being the happy case, Chapple kept the S-38 on the surface and headed out on his projected escape route to the northwest.

An hour later, with the afternoon still young, lookouts reported what appeared to be two Japanese destroyers cruising about 12 miles distant on the seaward side of the reef. To avoid being detected, Chapple promptly “pulled the plug.” The boat was barely submerged when she hit heavily on the bottom. Then, moving forward, she rammed into an underwater obstruction. The force of the collision shook the S-38 from stem to stern, knocking crewmen in all directions, smashing the outer glass on gauges, and splintering paint on bulkheads. This was too much for Chapple. Neither he, nor his crew, nor his boat could stand any more of this underwater punishment. In spite of the two destroyers, he decided to battle-surface and, if he had to, make a running fight for deep water on the seaward side of the reef. This was a fortunate decision, because the “destroyers” turned out to be small auxiliary craft which did not even see the S-38.

Several hours later on that eventful Christmas Day, Lieutenant W. G. “Moon” Chapple and his courageous crew, having successfully worked the S-38 over the reefs and out of Lingayen Gulf, were safe and Manila-bound. As darkness descended and cloaked them from prying enemy eyes, all hands were firmly convinced that the proverbial cat with nine lives had nothing on them.

The experiences shared by the officers and men of the S-38 during the four torturous days they spent in Lingayen Gulf, welded them into a closely knit group and, as Rear Admiral W. G. “Moon” Chapple proudly stated, “We will all be like brothers to the end of our days.”