THE LITTLE GIANT-KILLER—USS HERON (AVP-2)

![]()

Three weeks after Pearl Harbor, when defeat after bitter defeat shrouded in gloom the spirits of Asiatic Fleet sailors, some sort of victory was urgently needed to bolster morale. On 31 December 1941, the most unlikely ship in the fleet, the little 900-ton seaplane tender Heron—all 175 feet of her—produced that victory.

Commanded by Lieutenant William K. Kabler, the Heron was stationed at Ambon in the Dutch Moluccas, when, on 29 December, came the news of another depressing setback: the destroyer Peary had been seriously damaged by bombs. In order to hide while making emergency repairs, the destroyer had put into a remote cove 300 miles to the north of Ambon, near Ternate in the Moluccas. Being the closest available ship, the Heron was ordered to go to the battered vessel’s assistance.

Late the following afternoon, the Heron reached Ternate via the south passage only to learn that the Peary, made seaworthy by a supreme effort of her crew, had departed for Ambon via the north passage. On receipt of this information, Kabler immediately headed back to Ambon.

It was 0930 on 31 December 1941. The Heron, on a southerly course, was steaming in the Molucca Sea at 10 knots when a four-engine seaplane was reported approaching at low level. General quarters sounded and all hands instantly manned battle stations. Because the plane resembled a Sikorsky VS-42, a type flown by the Dutch, Kabler ordered his gunners to hold fire until positive identification had been made. With guns loaded and ready, all eyes strained to ascertain whether the big plane barreling in on them was friend or foe. A few hundred yards from what he judged to be the bomb-release point, Kabler detected red “meatballs” painted under the wings, and gave the order to open fire.

The Heron’s two obsolete 3-inch antiaircraft guns and her four .50-caliber machine guns opened up with a blistering barrage, and some of the .50-caliber guns found their mark. Such an unfriendly welcome from what probably looked like a defenseless merchant ship must have stunned the Japanese, for the bomber abruptly veered away. After climbing much higher, it began a run from the port beam. While his gunners hammered away, Kabler steamed his ship at maximum speed—slightly more than 11 knots—and cannily maneuvered so that the bombs, two 100-pounders, exploded harmlessly 1,500 yards off the port beam. When the enemy circled to attack from the port bow, he again outfoxed the bombardier, and two more bombs fell 300 yards off his starboard bow.

For more than an hour the bomber harassed the Heron with real and fake bombing runs until a rain squall suddenly came up and blanketed the ship, giving all hands a welcome respite. But the squall ended at 1120, and the Heron broke into the clear to find the pesky flying boat sitting on the water a few hundred yards off her starboard quarter. As soon as they could be brought to bear, all guns opened up on the bomber, which took off like a scared duck and was soon out of range.

As were the commanding officers of all seaplane tenders, William “Bill” Kabler was a naval aviator. Furthermore, he was a qualified bomber and torpedo-plane pilot. When he saw the big seaplane circling his ship at a safe distance instead of flying off, he correctly guessed that reinforcements had been called to the scene and the Heron was about to be subjected to more determined attacks. Although he knew no planes were available to come to the rescue, he radioed his situation to commander, Patrol Wing 10. The Heron must face alone whatever fate had in store. For four hours she continued on course, all the while being shadowed by the enemy plane. Then, at 1520, Bill Kabler’s fears materialized: six more four-engine bombers, flying in two three-plane sections of “Vs,” appeared. One section moved directly in to attack from his port quarter. Kabler fixed it with a steady eye and, when it reached the bomb-release point, abruptly maneuvered his ship from her projected course, as twelve 100-pound bombs burst 200 yards astern.

Immediately, the second section attacked from his starboard bow and dropped six 100-pounders, all of which fell more than 200 yards to starboard. This time, as the bombers bored in for the kill, a shell from one of the Heron’s 3-inch guns scored a direct hit on the outboard starboard engine of the right-hand plane in the formation. The sight of the big bomber, trailing black smoke, falling out of formation and retiring to the northwest brought a cheer from the Heron’s crew.

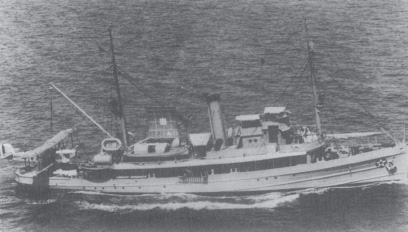

The seaplane tender USS Heron (AVP-2), as she looked in the 1920s. National Archives, 80–G–466184

In a determined effort to finish off the little ship, the two remaining planes of the section wheeled and charged back from her port bow to drop four more 100-pound bombs. Although these fell uncomfortably close, they did no damage.

It was nearly 1600 when the seaplanes, their bombs expended, winged away. Just as it appeared that a terrifying encounter had at last been terminated, five twin-engine, land-based bombers came swooping in from the Heron’s port bow at a fairly low altitude. Until this moment the ship’s .30-caliber machine guns had been outranged. Now, every gun on board went into action. Their fire was so intense and the Heron’s maneuvers so erratic that the attack was aborted, but not before several of the planes were stung by bullets.

For fifteen minutes or so, these planes licked their wounds as they circled at a safe distance, then made a medium-level attack again from the ship’s port bow. As they came within range, the Heron’s gunners took up the fight. Although the .50-caliber bullets seemed to be scoring hits, the planes sped ever closer to the bomb-release point, posing a horrendous dilemma for Kabler. The ship’s slow speed precluded his making the sharp turns and sudden speed changes required to throw off this determined attack. When he saw the bomb bays open and the ominous black projectiles tumbling toward his ship, Bill Kabler knew there was nothing he could do. Screaming like tormented souls, twenty 100-pound bombs rained down on the hapless little Heron. Miraculously, most of them missed, but three exploded 15 yards off her port bow and a fourth hit directly on top of her mainmast. Sickening tremors ran through the ship as she heaved and rolled with the force of the explosions. Death and destruction stalked her decks. Her port 3-inch antiaircraft gun was knocked out and every man in its crew was wounded, as were the crews of the port side machine guns. A lookout was killed instantly and another seaman mortally wounded. In all, the crew suffered twenty-eight casualties, almost half the ship’s complement.

Damage to the Heron was considerable, but it was nothing compared to what might have happened had the bomb that hit atop her mast instead exploded in her guts. Twenty-five shrapnel holes, varying in size from 1 to 10 inches, pockmarked her port side forward from the waterline to the main deck. All three of the ship’s boats were studded with holes and the engines of two of them were damaged. The emergency radio was knocked out, and there was considerable minor damage topside, including a stubborn fire in a forward storeroom which smouldered and resisted all efforts to put it out for nearly three hours. The battered Heron was still seaworthy and her sadly mauled crew was grimly determined to fight her to the death.

The harrowing task of tending the wounded got under way, while wary eyes kept track of the bombers circling the ship out of gun range. All hands dreaded another attack, but stood ready to meet it if it came. That eventuality, however, failed to materialize and, with intense relief, the Heron’s beleaguered crew saw the bombers suddenly turn and fly away. But their ordeal was not yet over. At 1645, even as the five land-based bombers diminished to specks in the distant sky, three more four-engine seaplanes were spotted streaking toward the ship at wave-top level. This was a torpedo attack, one plane coming in on each bow, and the third on the port quarter. All operable guns were manned on the double, some by wounded seamen who refused to stay out of the fight. Angry, rattling bursts of machine-gun fire and the rhythmic, sharp crack of the remaining 3-inch gun greeted the onrushing seaplanes. Bill Kabler, as he had done throughout the day, maneuvered his ship to take evasive action. This time, however, he was grimly aware that to avoid three torpedoes launched simultaneously from three directions was going to take more than skill. What is known in the navy as the “J,” or Jesus, factor had to be cranked into the problem in a big way.

As luck would have it, the Japanese planes did not coordinate their attack and launched their torpedoes several seconds apart. Kabler turned, stopped, and backed his ship. The three torpedoes missed. They had come frightfully close, but the miracle was—they missed.

During the attack, the seaplane that approached on the port quarter was shot up by the Heron’s guns and forced to land. Thereupon, the pilots of the two remaining planes, their common sense probably overcome by anger and frustration, made strafing runs on the Heron. Their light machine guns did only superficial damage to the ship but, for their efforts, both planes were hit repeatedly by the Heron’s .50-caliber guns. One of them appeared to be seriously damaged, and both beat a hasty retreat westward.

When the sky was clear of enemy planes, Kabler maneuvered the Heron close to the sinking seaplane, which had been abandoned by its crew, and, with deliberate gunfire, blew it to bits. He then tried to pick up the plane’s eight-man crew swimming in the sea, but they stubbornly refused to grasp the lines thrown to them. His ship being overburdened with casualties, most of whom were in dire need of shore-based medical treatment, Kabler had no time to spare. After making several earnest attempts to rescue the Japanese, he left them to their own devices and headed the Heron full speed for Ambon.

After eight punishing hours, the sky was at last clear of enemy planes and, with darkness enveloping her, the Heron was safe. A little giant-killer, if there ever was one, she had survived ten attacks by fifteen planes which unleashed forty-six bombs and three torpedoes. In the process, she had shot down one four-engine patrol bomber and so severely damaged several other planes that their ability to make the long flight back to base was doubtful. Overall, the outcome was a glorious tribute to the Heron’s crew and to her commanding officer, Lieutenant William L. Kabler, who, throughout the long torturous day, kept his cool and maneuvered his ship superbly.

The USS Heron’s battle against fearful odds was but a straw in the tumultuous winds of war, yet, to the anguished men of the Asiatic Fleet, it was a victory of magnificent proportions.