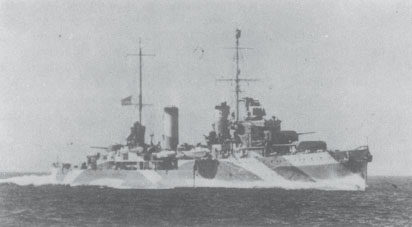

THE HEAVY CRUISER USS HOUSTON (CA-30)

![]()

The Japanese claimed to have sunk the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30), flagship of the United States Asiatic Fleet, so many times during the first three months of World War II that she was nicknamed “The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast.” On several occasions she had come perilously close to fulfilling those pronouncements, but it was not until the night of 28 February 1942 that her luck ran out and, off the northwest coast of Java, Houston vanished with all hands. The mystery shrouding the cruiser’s fate persisted until the war’s end, when groups of half-dead survivors were discovered in Japanese prison camps scattered from the Netherlands East Indies, through the Malay peninsula, the jungles of Burma and Thailand, and northward to the islands of Japan.

Of Houston’s 1,087 officers and men, 721 went down with the ship and 366 escaped, only to be captured as they floundered helplessly in the sea or attempted to penetrate the wilds of Java. Of the original survivors, 76 died, but 290 somehow managed to live through the ordeal of filth, starvation, and brutality meted out to them during three and one-half years as Japanese prisoners of war.

What happened to the Houston that night is a nightmare of many years standing, yet each incident lives in my mind as though it occurred only yesterday. Near sundown of that fateful evening of 28 February 1942, Houston, in company with the Australian light cruiser Perth, steamed out of Tandjungpriok, the port for Batavia, Java, heading for Sunda Strait. I stood alone on the Houston’s quarterdeck contemplating the placid green of the Java coast as it slowly fell astern. Often I had found solace in its beauty, but this time it seemed only a mass of coconut and banana palms that had lost all meaning. Like the rest of the Houston’s crew, I was physically and mentally exhausted from four nerve-racking days of incessant bombings and battle, and was deeply preoccupied with the question that gnawed at every man on board, “Will we get through Sunda Strait.”

True, Captain Rooks of the Houston and Captain Waller of the Perth had visited the British Naval Liaison Office in Batavia, where by telephone to Supreme Allied Naval Headquarters at Bandung they had been informed that a Dutch navy reconnaissance plane had reported as late as 1500 that no Japanese sea forces were within ten hours steaming time of Sunda Strait. That was a pleasant thought, but what about the Japanese cruiser planes which had shadowed us throughout the day? The ships from which they had been launched could not be far away, and certainly they were well aware of our movements. There was also the possibility that enemy submarines would be stationed throughout the length of Sunda Strait, between Java and Sumatra, to intercept Allied ships attempting to escape from the Java Sea into the Indian Ocean.

Although there appeared to be little room for optimism, there had been other times when the odds had been heavily stacked against us, and somehow we had managed to battle through. Perhaps I was just a plain damn fool, but I could not bring myself to believe the Houston had run her course. With a feeling of shaky confidence, I turned and headed for my room. Having just been relieved as officer-of-the-deck, I found the prospect of a few hours rest most appealing.

The wardroom and interior of the ship through which I walked was dark, for the heavy metal battle ports were bolted shut, and white lights were not permitted within the darkened ship. Only the eerie blue beams of a few battle lights close to the deck served to guide my feet. I felt my way along the narrow companionway, and briefly snapped on my flashlight to seek out the coaming of my stateroom door. As I stepped into the cubicle that was my room, I quickly scanned the place and switched off the light. There had been no change. Everything lay as it had for the last two and a half months. There had been only one addition in all that time. It was Gus, my silent friend, the beautiful Bali head I’d purchased six weeks before in Surabaja.

Gus sat on top of my desk lending his polished wooden expression of absolute serenity to the cramped atmosphere of the room. In the darkness I felt his presence as though he were a living thing. “We’ll get through, won’t we, Gus?” I found myself saying. And, although I could not see him, I thought he slowly nodded.

I slipped out of my shoes and placed them at the base of the chair by my desk, along with my tin hat and life jacket, where I could reach them quickly in an emergency. Then I rolled into my bunk and let my tired body sink into its luxury. The bunk was truly a luxury, for the few men able to relax lay on the steel decks by their battle stations. I, being an aviator, with only the battered shell of our last seaplane left on board, was permitted to take what rest I could get in my room.

Although there had been little sleep for any of us during the past four days, I found myself lying there in the sticky tropic heat tossing fretfully and yearning for sleep that would not come. The hypnotic hum of blowers thrusting air into the bowels of the ship, the Houston’s gentle rolling as she cleaved through a quartering sea, and the occasional groaning of her steel plates combined to parade through my mind the mad sequence of events that had plagued us during the past few weeks.

Twenty-four days had elapsed since that terrifying day in the Flores Sea, yet there it was haunting me again as it would for the rest of my life. From my vantage point on the signal bridge I saw ahead of us the Dutch light cruiser De Ruyter, on board which was the striking force commander, Rear Admiral Karel Doorman. Behind the Houston steamed the only other American cruiser in all of Southeast Asia, the old light cruiser Marblehead. She was followed by the Dutch light cruiser Tromp. Screening our line of ships were the Dutch destroyers Van Ghent, Piet Hein, and Bankert, along with the American destroyers Bulmer, Stewart, John D. Edwards, and Barker. We were en route to attack an enemy convoy in the vicinity of Makasar Strait. This was to be the Houston’s initial engagement with the Japanese, and all hands were excited with the prospect of battle and victory. But the doughty little fleet would never reach its objective.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, enemy planes were sighted in the distant sky heading in our direction. The shrill bugle call “air defense” immediately sounded in raucous concert with the clanging gongs of “general quarters.” All hands rushed to battle stations as 54 twin-engine bombers, flying in six nine-plane formations, circled out of gun range to commence their attacks.

On the first bombing run by a nine-plane section, the planes appeared to be within easy reach of our 5-inch antiaircraft guns. The batteries opened fire. Wide-eyed we watched, anticipating the blasting of enemy planes from the sky. But something was wrong. Although our gunners rapidly fired shells into the sky, we were appalled to see most of them failed to explode at altitude. The Houston was cursed with faulty ammunition. A bursting shell staggered the lead plane, but all of them continued on course. Bomb bays opened and down tumbled the black projectiles of death and destruction.

The bombs, large armor-piercing ones, straddled the Houston. Detonating well beneath the surface, they spewed up great volumes of water as high as the main director atop the foremast. The force with which they exploded lifted the big cruiser, as though by some giant hand, and tossed her yards away from her original course. Men were dashed to the decks, but there were no casualties. Our principal antiaircraft director, however, was wrenched from its track, rendering it useless, and the Houston was taking on water from sprung plates in the hull.

The attacks continued to be concentrated on the Houston and Marblehead. Even with faulty shells it was only the steady barrage from our antiaircraft guns and the skillful shiphandling by Captain Rooks that kept the Houston from the realms of Davy Jones. For over two hours we successfully evaded the bombs and, in the process, even knocked down three planes and damaged others. But our luck was running out.

All at once, bombs dropped on the Marblehead sent geysers of water leaping into the air, engulfing the old cruiser from stem to stern. When the curtain of water settled back into the sea, there were fires amidships and near her after turret. She suffered two direct bomb hits, one of which jammed her rudder hard to port, and she could take evasive action only by steaming in a circle. Near misses gouged holes in her forward hull, and she was shipping water at an alarming rate. Captain Rooks rushed the Houston close to the stricken ship, hoping to fend off the attackers with our guns. But now it was the Houston’s turn.

“Stand by for attack to port,” bellowed from the ship’s loudspeakers, and immediately all eyes shifted from the smoking Marblehead to the sky. There they came again, nine more of the bastards. Guns commenced tracking the oncoming enemy, then opened fire. Salvo after salvo sped from their flaming muzzles, but the determined attack was pressed home. When the bombs were seen falling, over the speakers came the command, delivered in cool, matter-of-fact tones, “Take cover. Take cover.” Those who could sought cover, others hit the deck. But the men on the 5-inch guns amidships stood fast and, as they had done throughout all other attacks, unflinchingly fired away. They were magnificent in their resolute performance of duty.

All but one of the bombs burst harmlessly in the sea off our port quarter, but the stray, released a fraction of a second late, nearly finished the Houston on the spot. There was a tremendous explosion aft. The big ship lurched and trembled violently. Crashing through the searchlight platform on the mainmast, the bomb cut a foot-long gash in a mast leg, ripped through the radio shack, and exploded at main deck level just forward of number 3 turret. Chunks of white-hot shrapnel slashed through the turret’s armor plate as though it were paper, igniting powder bags in the hoist. In one blazing instant, all hands in the turret and in the handling rooms below were dead. Where the bomb spent its force, it blew a gaping hole in the deck beneath which the after repair party had been stationed. They were wiped out almost to a man. The damnable battle ended with forty-eight of our shipmates killed and another fifty seriously burned or wounded.

Desperately I strove to rid myself of that gruesome picture—the blazing turret, the bodies of the dead sprawled grotesquely in pools of blood, and the numb, bewildered wounded staggering forward seeking medical aid—but I was forced to see it through. I heard hammers banging, hammers that pounded throughout long hours as weary men steadily worked building coffins for their shipmates lying in covered little groups on the fantail.

The following day we put into Tjilatjap, that stinking, fever-ridden little port on the south coast of Java. The bomb-damaged Marblehead limped in behind us several hours later with thirteen men killed and more than thirty wounded. When the Marblehead passed the Houston close aboard, the crews of both ships lined the rails and cheered in spontaneous acknowledgement of mutual admiration and respect.

Sadly, we unloaded our wounded and prepared to bury our dead. In the hum of the blowers, I detected strains of that mournful tune the ship’s band had played when we carried our fallen comrades through the heat of those sunbaked, dusty streets at Tjilatjap. I saw again the silent, sarong-clad natives who watched as we placed our dead in the little Dutch cemetery bordering the sea, and wondered what they thought of all this.

The scene shifted. Only four days had elapsed since we steamed through the minefields protecting the beautiful port of Surabaja. Air raid sirens whined throughout the city and lookouts reported bombers in the distant sky. Large warehouses along Rotterdam Pier were burning, and a sinking merchant ship lay on its side vomiting dense black smoke and orange flames. The enemy had come and gone, but left his calling cards. Anchored in the stream a few hundred yards from the docks, we silently watched soldiers of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army methodically work to extinguish the fires.

Six times during the next two days we experienced air raids. Lying at anchor, we were as helpless as a duck in a rain barel. That the men of the 5-inch gun crews did not collapse is a tribute to their sheer guts and brawn. Resolutely they stood by their guns, beneath the searing equatorial sun, slamming shell after shell into the sky while the rest of us sought what shelter was available in that bull’s-eye of a target.

Time and again bombs, falling with the deep-throated swoosh of a giant bullwhip, exploded all around us spewing water, shrapnel, and even fish over our decks. Docks not far away were demolished and a Dutch hospital ship was hit, yet “The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast” still rode defiantly at anchor.

When the siren’s baleful wail sounded the all clear, members of the Houston’s band came from battle stations to the quarterdeck, where all hands gathered to clap and stomp as they played swing tunes. God bless the American sailor, you can’t beat him.

Like Scrooge, I continued to be haunted by ghosts of the past. I saw us in the late afternoon of 26 February 1942, standing out of Surabaja for the last time. In tactical command of our small striking force was Rear Admiral Karel Doorman of the Royal Netherlands Navy. His flagship, the light cruiser De Ruyter, was in the lead followed by the heavy cruiser Exeter of Graf Spee fame. Next in line came the Houston, whose bomb-shattered number 3 turret was beyond repair. The light cruisers Perth and Java, in that order, were last in the line of ships. Nine Allied destroyers; four American, three British, and two Dutch; comprised the remainder of our force. We slowly passed gutted docks where small groups of old men, women, and children had gathered to wave tearful goodbyes to their loved ones, most of whom would never return.

Our small, hastily gathered force had never operated together as a unit. Communications among ships of three different navies was poor at best. Orders from Vice Admiral Conrad E. L. Helfrich, commanding the American, British, Dutch, and Australian naval forces (ABDAFLOAT) for defense of the Netherlands East Indies,* were vague. We had no battle plan, only the grim directive from the ABDA naval command, “Continue attacks until enemy is destroyed.” We knew only that we were to do our utmost to break up one of several Japanese invasion fleets bearing down on Java—even though it might mean the loss of every ship and man. This was a last-ditch attempt to save the Netherlands East Indies, which were doomed regardless of the outcome.

All night long we searched for the enemy convoy, but it seemed to have vanished from its reported position. At 1415 the next afternoon we were still at battle stations and about to return to Surabaja when reports from air reconnaissance indicated that the enemy we sought was south of Bawean Island and heading south. The two forces were less than 50 miles apart.

A hurried but deadly serious conference of officers was immediately held in the Houston’s wardroom. Commander Arthur L. Maher, our gunnery officer, explained that our mission was to sink or disperse the protecting enemy fleet units, then destroy the convoy. My heart pounded with excitement, for the battle, to be known as “The Battle of the Java Sea,” was only a matter of minutes away. I wondered if the sands of time were running out for the Houston and all of us who manned her. At that moment, I would have sold my soul for the answer.

In the darkness of my room the Japanese came again, just as I had seen them from my duty station on the bridge. At 1615 a British destroyer in the van signaled, “Two battleships to starboard.” With this, my heart froze, for battleships, with their huge guns, could stand off beyond our range and blast us all to bits. A minute later, this awful thought was dispelled by a correction to the report which read, “Two heavy cruisers.”

The Houston’s foretop spotter reported the enemy ships bearing 30 degrees relative to starboard. I strained my eyes and finally made out two small dots on the far horizon. With each passing minute they grew larger until their ominous, pagoda-shaped superstructures became clearly visible. They were Nachi-class heavy cruisers, each armed with ten 8-inch guns in five turrets, and eight 21-inch, long-range torpedoes in addition to powerful secondary batteries.

I watched, transfixed, as sheets of copper-colored flame erupted from the enemy ships, and black smoke momentarily masked them from view. My heart pounded and cold sweat drenched my body as I realized the first salvos were on the way. Somehow those big guns all seemed aimed at me. I wondered why our guns did not open fire, but when the shells fell harmlessly 2,000 yards short, I understood that the range was still too great.

Suddenly, masts were reported dead ahead. These, we anxiously hoped, were the transports. They rapidly developed into a forest of masts and then into ships which climbed in increasing numbers over the horizon. To our dismay, they were identified as two flotillas of destroyers, six in one, seven in the other, and each led by a light cruiser. Now the situation had taken a drastic change. Because the Exeter’s after turret was malfunctioning and could not be brought to bear on the enemy, and the Houston’s number 3 turret was destroyed, we had only ten 8-inch guns between us against twenty for the Japanese. We were both outnumbered and outgunned.

At 30,500 yards, the Exeter opened fire, quickly followed by the Houston. The sight of the Exeter’s big guns firing and the attending heavy booms so fascinated me that I was caught unprepared when the Houston’s main battery let go. Concussion from our gun blasts knocked me against a bulkhead and tore off my helmet, sending it bounding along the deck. Although shaking with excitement, I recovered my helmet to discover that the tensions induced by waiting for the battle to begin had magically vanished. It was heartening to hear a battle-phone talker relay a report from spot 1, “No change in opening range.” The Houston was close to target.

The range closed rapidly and soon all cruisers were joined in a furious battle. The Houston’s fire was directed at the rear enemy heavy cruiser. The Exeter and our light cruisers seemed to be engaging the Japanese light cruisers, which by now were broad on our starboard beam. For the first fifteen minutes, the enemy completely ignored the Houston, concentrating their fire on the De Ruyter and the Exeter. After their initial salvos, their shells were falling dangerously close to our lead ships.

From the onset, the Houston’s shells had landed close to her target. She was the only ship firing shells with dye in them to mark their fall. When they exploded in the water, they kicked up blood-red splashes. There was no mistaking where the Houston’s heavy shells were landing. Following our sixth salvo, spot 1 reported, “Straddle.” On the tenth, the Houston scored her first effective hit, and a brilliant fire broke out in the vicinity of the heavy cruiser’s forward turrets. In succeeding salvos, additional hits were observed. By 1655, the cruiser was aflame both forward and amidships. She ceased firing and turned away under dense smoke from the fires and her funnel. The Houston had drawn first blood.

Enemy cruisers were concentrating fire on the Exeter. To give her relief, the Houston engaged the remaining heavy cruiser. Spotters reported hits, but there was no visible damage. The Exeter, meanwhile, scored a direct hit on one of the light cruisers, forcing it, smoking and on fire, out of the action. Despite the loss of two cruisers, the fall of enemy shells did not seem to diminish, and salvo after salvo ripped into the sea around us. I was mesmerized by the savage flashing of enemy guns, and the sight of their deadly shells flying toward us like flocks of black birds.

Suddenly, we were in a perilous position. A salvo of 8-inch shells exploded close to our starboard side, quickly followed by another to port. This was an ominous sign that the Japanese had at last zeroed in on the Houston, and the next salvo could spell disaster. Fearfully we waited. With high-pitched screams the shells came hurtling down to explode all around us. It was a perfect straddle, but not a hit was sustained by the Houston. Four more screaming salvos followed, but miraculously we remained unscathed. At the same time, the Perth, 900 yards astern, was straddled eight times in a row, yet she too continued to fight without so much as a scratch.

About ten minutes later, enemy destroyers attempted a torpedo attack. The two flotillas raced toward us, but gunfire from our light cruisers turned them back. The Perth claimed one destroyer sunk and another damaged in this abortive effort. But the Japanese were not to be denied. They re-formed and, with a light cruiser leading, charged in again as a single coordinated group. This time, instead of thirteen destroyers, there were only twelve. They were heavily engaged by the Exeter and the light cruisers, while the Houston continued dueling with the remaining heavy cruiser. Hits were observed on enemy destroyers, but they pressed on. At 17,000 yards they launched torpedoes and immediately retired under heavy smoke. It was estimated that it would take almost fifteen minutes for those deadly “tin fish” to reach us.

At this juncture, the heavy cruiser previously damaged by the Houston returned to attack the rear of our column. Whatever damage she sustained evidently was under control, but her rate of fire was considerably reduced. The light cruiser Java was hit by a 6-inch shell, but there were no injuries and it did little damage. An 8-inch projectile ripped into the Houston. Passing through the main deck, aft of the anchor windlass, it penetrated the second deck and exited through the starboard side just above the waterline, without exploding. Another ruptured an oil tank on the port side aft, but did little damage as it too failed to explode.

It was not about 1725, and the vicious tempo of the battle was stepping up. Heavy shells exploding in the sea often threw water over the Houston’s decks. Accuracy of the Japanese gunfire left no doubt that someone was going to be hit seriously. Throughout this madness, all hands were uncomfortably aware that those damnable torpedoes were knifing through the sea toward us, yet Admiral Doorman gave no orders for evasive action.

Suddenly, a billowing white cloud of steam was seen venting amidships from the Exeter. She had been hit by an 8-inch shell which killed the four-man crew of her S2 4-inch gun, slashed through several steel decks, and exploded in number 1 boiler room. Six of her eight boilers were instantly knocked out of commission, and around them lay ten dead British seamen. The seriously crippled Exeter’s speed rapidly fell off to 7 knots.

In a desperate attempt to avoid the oncoming torpedoes, Captain Oliver L. Gordon immediately turned the crippled cruiser to port. Captain Rooks, believing he had missed a signal from Admiral Doorman for a simultaneous turn of ships from line ahead to line abreast, turned the Houston with the Exeter. And when Captain Waller of the Perth and Captain Van Staelen of the Java saw the two ships ahead of them turn, they too swung to port. Instant confusion reigned in the Allied fleet. Without orders, the three groups of American, British, and Dutch destroyers made off in various directions. Left no alternative, Admiral Doorman quickly ordered the De Ruyter turned to port, thereby joining in a logical defensive maneuver he should have ordered in the first place.

Before the Perth had completed her turn, Captain Waller realized the Exeter’s predicament and abruptly pulled his ship back out of the line. With volumes of thick black smoke pouring from her funnels, the Perth raced around the Houston to screen the Exeter from the Japanese. Then, to add to the confusion, lookouts reported three additional enemy cruisers with six destroyers on the horizon to starboard.

At that moment, the water became alive with torpedoes, which seemed to be running in all directions. A seaman standing near me shouted, “Jesus Christ, look at that!” I whirled to look in the direction he was pointing and could hardly believe my eyes. Immediately off our starboard bow a gigantic pillar of water was rising to a height of more than 100 feet. Directly beneath it, with only small portions of her bow and stern showing, was the Dutch destroyer Kortenaer. She had been racing to change stations when a torpedo aimed at the Houston blew her guts out. With her back broken, she rolled over and jackknifed. When the water pillar slumped back into the sea, only the bow and stern sections of the ship’s keel remained above water. A few hapless men could be seen scrambling for their lives to cling to her barnacled bottom while her twin propellers, in their dying propulsive effort, slowly turned over in the air. In less than a minute, the Kortenaer had vanished beneath the Java Sea. No ship stopped to look for survivors, for any one that did could have easily shared the same fate.

Now all Allied ships were making black smoke to hide the Exeter from the enemy. The sea for miles around was so heavily curtained with smoke that to determine accurately who was where, or what Admiral Doorman had in mind for his next maneuver was impossible. Occasionally a Japanese scouting plane circled out of gun range to relay our fleet’s disposition, course, and speed back to his flagship. The confused mass of Allied ships steaming in various directions must have produced some wild and perplexing reports.

Eventually, through the smoke, the De Ruyter was spotted flying her usual “follow me” signal. The Houston and the other cruisers attempted to fall in line while firing on enemy ships to prevent their closing on the Exeter. To further complicate the situation, the sea still bubbled with torpedo wakes, and it took extreme vigilance to avoid them. Throughout this period, the waters around us occasionally erupted with strange explosions. These, it was finally determined, were caused by enemy torpedoes self-destructing at the end of their runs.

Foretop spotters reported many enemy ships moving to penetrate the smoke screening the Exeter. Only the British destroyers Electra, Jupiter, and Encounter were in position to meet this attack. With traditional British courage, they resolutely charged to intercept this numerically superior force.

The Electra, first to make contact, broke through the dark curtain of smoke into the brilliant sunshine and was immediately engaged by Japanese destroyers, the tail end of a force consisting of seven destroyers led by a light cruiser. The fight grew to savage proportions when the cruiser, followed by the other destroyers, wheeled back to do battle. The Encounter and Jupiter arrived on the scene just as the Electra was blasted into a flaming hulk. But, before she went under, Electra scored hits on the cruiser and a destroyer.

The Encounter and the Jupiter exchanged fire with the Japanese until our cruisers moved into position to take up the fight and permit them to move back behind the protective smoke screen. The Japanese, realizing they were outgunned, hightailed it out of range. The attack was broken up and the Exeter saved, but it was depressing to know that the Electra and her valiant crew had been lost.

The action continued to be extremely confused. The Houston was maneuvering to fall in line behind the De Ruyter when a Japanese destroyer broke through the smoke not 2,000 yards dead ahead. Our main battery, alert and ready, fired a salvo of 8-inch shells which virtually tore the ship apart. She was there one moment and gone the next.

By this time, the Exeter had managed to build up speed to 10 knots, and the Dutch destroyer Witte De With was ordered to escort her back to Surabaja. Then, with his column once more assembled, Doorman returned to the attack. At a range of about 20,000 yards, the ships continued the engagement. Hits were observed on several enemy ships, but with no telling effect, and the Allies suffered no more than near misses. This part of the battle lasted less than fifteen minutes and the admiral, to conserve ammunition for use against transports, turned his force to the south in an effort to break off the engagement.

As his cruisers steadied on course, Doorman signalled to the American destroyers, “Counterattack.” He quickly followed that with, “Cancel counterattack—make smoke.” A few minutes later he signalled, “Cover my retirement.” By this time the American destroyer captains were thoroughly confused and far from certain what the man had in mind. It was determined, however, that the last directive meant they should attack the enemy cruisers, which were following uncomfortably close. Braving heavy enemy fire, the old four pipers John D. Edwards, Alden, Paul Jones, and John D. Ford pressed to within 10,000 yards. To move in further would have been sheer suicide and, at extreme range, they launched torpedoes. At times, enemy shells splashed dangerously close, but the courageous destroyermen brought their ships back unharmed.

During the attack, the Houston’s main battery fired on what appeared to be two heavy cruisers not previously encountered. The Perth also fired on them, and the Japanese warship was engulfed in flames fore and aft. With that, Commander Maher shifted his attention and the Houston’s guns to other targets. Though Maher could not confirm this ship sunk, observers on board the Houston, Perth, and other Allied ships reported seeing a violent explosion, following which the enemy cruiser disappeared stern first beneath the sea.

The daring torpedo attack failed to damage any enemy ships, but it forced the Japanese to turn away, terminating the engagement. It was then 1830. The battle had lasted for over two hours. Such a time span was contrary to the thinking of most naval strategists, for it was believed gunnery and torpedo fire had been developed to such a fine point that a naval engagement would be decided in a matter of minutes. Perhaps the assumption was sound, provided the battle was conducted in accordance with the book, but the likes of this fouled up fight were not contained in any book.

The afternoon had been filled with blood-boiling tensions, and the brief lull, during which hastily prepared sandwiches and coffee were served, was a godsend. Although there was a modicum of comfort in knowing we were still alive, all hands were haunted by the agonizing question, “How much longer can our luck hold out?” Admiral Doorman, we knew, was determined to intercept the transports and, if necessary, die in the attempt. That he might kill us all in the process was not a pleasant thought.

We checked our losses. The destroyers Kortenaer and Electra had been sunk. The crippled Exeter, escorted by the destroyer Witte De With, had retired to Surabaja. The four American destroyers, out of torpedoes and running low on fuel, also had withdrawn to Surabaja. Only the two British destroyers, Jupiter and Encounter, remained with us. The cruisers Houston, Perth, De Ruyter, and Java, showing the jarring effects of continuous gunfire, were still in the fight.

Our main battery was in sad shape. The guns of both turrets were less than 40 rounds away from their designed life expectancy of 300 rounds per gun. Even then their accuracy was questionable. That afternoon they had fired so rapidly for such a sustained period of time that the liners in the gun barrels crept out an inch or more. The casings were so hot that it would be hours before they could be touched. To add to the Houston’s predicament, only 50 rounds of 8-inch shells per gun remained.

The ventilating system in the magazine areas had proven totally inadequate. Men on the shell decks passed our during the battle from the oppressive heat and the physical exertion required to keep the guns supplied with ammunition. Adding to the hardships of the gun crews, melted grease from the gun slides lay 2 inches deep in the pits, making the platforms treacherously slippery. A 1-inch deep pool of water and sweat in the powder circles made footing extremely hazardous, especially with the ship maneuvering at high speed, and caused the wetting of trays and the dampening of powder. The situation was no better in the bowels of the ship, where the chief engineer reported his force, which had suffered more than seventy cases of heat prostration during the battle, was on the verge of complete exhaustion.

After sunset, Admiral Doorman led his remaining ships on a northerly course. At 1930, enemy warships were reported to port. At the same instant, the darkness was shattered when the Perth fired a spread of star shells. We strained our eyes, but could see nothing. To elude enemy ships lurking in the darkness, we abruptly changed course to the east. Twenty minutes passed without a sign of the enemy. Then, all of a sudden, night became day as a parachute flare burst above us. Blinded by the brilliant, greenish light, and helpless to defend ourselves, we stood by, fearful that the unseen enemy was closing in for the kill.

One after another the flares burst in the sky, burned, and slowly fell into the sea. On board ship, men spoke in hushed tones, as though their very words might expose us to the enemy. Only the rush of water, as our bow knifed through the Java Sea at 30 knots, and the continuous roaring of blowers from the vicinity of the quarterdeck, were audible. Death stood by, ready to strike. No one talked of it, although all thoughts dwelt upon it.

Following the eighth flare, we tensely awaited the next. It failed to come, and once again we were cloaked in darkness. No attack materialized and, as time passed, it became evident that the unseen plane which dropped the flares had gone. How wonderful the darkness, yet how terrifying to think that the enemy was aware of our movements, and was merely biding his time to strike.

The flares caused Admiral Doorman to change course to the south. When the dark mountains of Java were seen silhouetted against the star-flecked sky, a westward course was set paralleling the coast. Some miles west of Surabaja, we headed into a large bay where it was anticipated the Japanese might attempt a landing. Our charts showed that these waters were not very deep, and when a large stern wave started to build up on either side of the fantail, Captain Rooks became alarmed, for this indicated the ship was endangered by shallow water. Suddenly, the Houston commenced vibrating violently and losing speed. Aware that his ship was running aground, Rooks instantly turned the Houston out of the formation and headed for deeper water away from the coast. Soon afterward, Doorman apparently realized his mistake, and led the other ships out of the bay, where the Houston rejoined the column.

Coincident with Doorman’s change of course, the British destroyer Jupiter, covering our port flank on the landward side, exploded in flames. “I am torpedoed,” she reported.* We were appalled, for there were no enemy ships in sight. Leaving the doomed destroyer to her fate, we raced away and continued blindly searching for the transports.

The moon, sometimes obscured by scudding clouds, aided our search, but for an hour we saw nothing of enemy warships. I climbed up on the forward antiaircraft director platform and sprawled out for a bit of rest before the inevitable shooting began. Hardly had my eyes closed when the sounds of whistles and shouting men jerked me to my feet. The water to starboard was dotted with men who hailed us in a foreign tongue. They were Dutch survivors of the destroyer Kortenaer, torpedoed during the day action, and the British destroyer Encounter was ordered to rescue the poor devils and take them to Surabaja.

Stripped of destroyers, all that remained of our little fleet were three light cruisers and one crippled heavy cruiser. On we steamed through the eerie night. Suddenly, six water-borne flares mysteriously appeared paralleling our line of ships. Aghast, we stared at these insidious lights, which resembled those round pots that burn with an oily yellow flame alongside road construction sites. No one could tell how they got there or what they were. Some thought they were mines, others thought their purpose was to mark our course for the enemy. Either possibility was disquieting.

As fast as we left one group of lights astern, another popped up alongside. As we continued on we could see behind us the unnerving lights, spread out for several miles, clearly defining our track. In zigzag lines, on the rolling surface of the Java Sea, they bobbed and glowed like fiendish jack-o’-lanterns. It was stupefying to know the enemy was following our every move. Then, as suddenly as they appeared, the lights stopped. Apprehensively, we continued on, searching for the elusive transports. When the enemy failed to strike, and the mysterious lights vanished in the night, we were grateful once again for the cloak of darkness.

The nerves of all hands were as taut as a hunter’s bowstring. There could be no relaxing. We were in an area charged with hostility. From our ships, hundreds of eyes peered into the night, seeking the enemy convoy we hoped would momentarily be within our grasp. The battle was bound to begin soon, and men wondered if these were their last living moments on earth.

At about 2300, lookouts reported two cruisers to port, moving on an opposite course. No friendly ships sailed within hundreds of miles of us, and all hands, standing keyed-up and ready at battle stations, knew this was the enemy. The sharp cracking of 5-inch guns ravaged the silence as the Houston attempted to illuminate the enemy with star shells. The first spread, fired at a range of 10,000 yards, was short. Rapidly, two additional spreads were fired at a range of 13,000 yards. Although they brilliantly illuminated the area, these too were short and served only to blind both sides temporarily. As the enemy ships drew away in the darkness, the Houston fired one main battery salvo with undetermined results. The shortage of 8-inch shells prevented firing more. The Japanese, however, fired three salvos, one of which straddled our stern. The encounter was brief, and both sides lost each other in the night as Admiral Doorman continued the wild, blind hunt for transports.

During the night, the order of ships in column was changed. The De Ruyter still maintained the lead, followed by the Houston, Java, and Perth, in that order. A half-hour passed without incident. It was almost midnight. The moon, partially obscured by clouds, was of little help in our search. All hands desperately wanted to end this mad game of blindman’s buff and settle the issue one way or another. All at once, our senses, numbed by fatigue and unrelenting tensions, were shocked back to terrifying reality. With the quickness of a lightning bolt, a savage explosion shattered the oppressive silence and the Java, 900 yards astern of the Houston, was instantly enveloped in flames which leaped high above her bridge.

At the same time, torpedo wakes foamed in the water around the Houston. Where they came from no one could tell, for the enemy remained invisible. The De Ruyter abruptly changed course to starboard. The Houston was about to follow when another tremendous explosion racked the De Ruyter. Monstrous, crackling flames licked over her bridge and spread like wild-fire over the ship’s entire length. We passed within 100 yards of this terrifying inferno as ammunition, detonated by the intense heat, sent white-hot fragments rocketing into the sky.

During the last precious moments he had left on earth, the courageous Admiral Doorman, who had resolutely carried out the directives from higher authority until the end, ordered the Houston and Perth not to stand by for survivors, but to retire to Batavia.

Captain Rooks, in a masterpiece of seamanship and quick thinking, maneuvered the Houston to avoid torpedoes that zipped past us 10 feet on either side. Then, joined by Perth, we raced away from the striken ships, and the killer enemy which still remained unseen. How horrible and depressing to leave our valiant comrades-in-arms to die in such a manner, but we were powerless to assist them.

With Admiral Doorman gone, Captain Waller in the Perth assumed command, for he was senior to Captain Rooks. We now faced the unsavory prospect of being the only Allied cruisers, other than the damaged Exeter, in all of Southeast Asia. Both of us, low on fuel and ammunition, were pitted against the entire might of the Japanese Navy and Air Force. Our only hope was somehow to elude enemy forces and escape into the Indian Ocean through Sunda Strait, which lay between Java and Sumatra.

Throughout the night, we followed the Perth as she zigzagged along at 28 knots. All hands stood at battle stations and all eyes sought to penetrate the darkness, looking for ships they prayed they would not find. With the dawn, it seemed a miracle to watch the sun come up, for there had been many times during those past fifteen hours when I could have sworn we never would.

The Houston was a wreck. During the battle, turrets 1 and 2 each had fired 101 salvos for a total of 606 8-inch shells. The concussions from those big guns, coupled with the shock waves from firing them, played havoc with the ship’s interior. Every unlocked desk and dresser drawer had been torn out and the contents spewed all over. In lockers, clothing was wrenched from hangers and dumped in muddled heaps. Pictures, radios, books, in fact everything not bolted down, had been jolted from normal places and dashed about.

The admiral’s cabin, once the shipboard home of President Roosevelt, was a deplorable sight. Broken clocks, overturned furniture, cracked mirrors, charts ripped from the bulkhead, and large chunks of soundproofing jarred loose from overhead added to the rubble underfoot.

The ship too had suffered. Steel plates along the Houston’s sides, weakened by near hits in previous bombing attacks, were badly sprung and shipping water. Glass windows on the bridge were shattered. Fire hoses, strung along passageways for emergency purposes, were leaking and caused minor flooding. The Houston, for sure, was battle-scarred and battle-weary, but there was still plenty of fight left in her.

Morale remained high, but the physical condition of the crew was poor. Most had not had a chance for anything one might call rest for more than four days because battle stations had been manned more than half that time, and freedom from surface contacts or air alerts had never exceeded four hours. This had caused meals to be irregular and inadequate. Nevertheless, the exhausted crew shrugged it off, for every man considered himself lucky to be alive, and was determined to give every last ounce of strength to bring the Houston through.

These events, and qualms about what lay in store, tortured my mind until at last my senses numbed and I relaxed in the arms of Morpheus. While I slept, Captain Rooks was on the bridge along with Lieutenant Harold S. Hamlin, Jr., the officer-of-the-deck, who was busy keeping station 900 yards astern of the Perth. Turrets 1 and 2 were manned with powder trains filled. The 5-inch battery was divided with the flight deck guns on the forward director, and the boat deck guns on the after director. The sea was calm, the night windless. A full moon silhouetted the foreboding, volcanic mountains of western Java. Saint Nicholas Point light, marking the entrance to Sunda Strait, was sighted, and the quartermaster noted that the time was 2315. All hands on deck were elated, for it seemed as though the Houston and Perth just might make it. But, at that moment, lookouts reported surface vessels dead ahead. Tensions mounted. At first it was hoped these were Dutch patrol boats known to be operating in the strait. Captain Rooks and Lieutenant Hamlin examined them closely through night glasses and concluded they were maneuvering much too fast for an ordinary patrol. Captain Rooks immediately ordered general quarters sounded and Hamlin, who was officer in charge of turret number 1, made a mad dash for his battle station.

Clang! Clang! Clang! Clang! Clang!, the nerve-shattering general alarm burst my wonderful cocoon of sleep. Through nearly three months of war, that gong calling all hands to battle stations had rung in deadly earnest. It meant only one thing, danger. So thoroughly had the bitter lessons of war been taught to the brash, heartless clanging of that gong that I found myself in my shoes before I was fully awake.

Clang! Clang! Clang! Clang! Clang! The alarm resounded along the steel bulkheads of the Houston’s deserted interior. I wondered what kind of deviltry now confronted us and felt depressed. Strapping on my steel helmet, I hurried from the room. As I did, a salvo from the main battery roared out overhead. The shock flung me against the barbette of number 2 turret. We were desperately short of those 8-inch bricks. I knew the boys were not wasting them on mirages. I groped my way through the empty wardroom and into the passageway at the after end.

At the base of the ladder leading to the deck above, a group of stretcher bearers and corpsmen was assembled. I asked what we had run into. They did not know. As I quickly climbed the ladder heading for the bridge, the 5-inch guns joined with the booming of the main battery. This was getting to be one hell of a fight. I paused on the communication deck where the pom-pom guns were getting into action. Briefly, I watched their crews working swiftly, mechanically in the dark as their guns pumped out shell after shell. I glimpsed the fiery streaks of tracers hustling out into the night. How beautiful, I thought, these emissaries of death.

Before I reached the bridge, every gun on the ship was in action. Their murderous melody was magnificent, reassuring. At measured intervals the thunderous crash of the main battery joined the sharp, random cracking of the 5-inch guns, and the steady pom, pom, pom of the 1.1s, while above it all, from platforms high in the foremast and mainmast, came the sweeping volleys of the .50-caliber machine guns, placed there to fight off low-flying aircraft but now finding themselves engaging surface targets.

My arrival on the bridge was greeted by a blinding flash and a thunderous boom as a salvo from number 2 turret raced out into the night. My eyes had just begun to refocus when a salvo from number 1 turret shattered the darkness, blinding me again. I wanted desperately to know what we were up against, but to ask would have been absurd. On the bridge, from the captain to the sailors manning the overburdened battle phones, everyone was grimly absorbed in fighting the ship. Eventually, by the bright flashes of her guns, firing on all sides, I distinguished the Perth several hundred yards ahead of us. Continuous gun flashes from many directions indicated that the Houston was the target for numerous men-of-war.

Outgunned as we obviously were, it would have made little difference to any of us to know we had rammed into the very midst of the largest amphibious landing operation yet attempted by the Japanese. Targets were on all sides and there was little room to be selective. Lining the shores of Bantam Bay, where most of the battle was fought, were sixty transports readying to unload troops and materials of war for the conquest of Java. Between us and the transports was a squadron of destroyers, led by a light cruiser and augmented by motor torpedo boats. A few miles behind us steamed two heavy cruisers, an aircraft carrier, and an unknown number of destroyers. Blocking the entrance to Sunda Strait were two heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, and ten destroyers. The Houston and Perth were trapped.

In attempting to fight through the encircling warships, the Houston and Perth were forced to make radical and violent maneuvers to evade torpedoes launched by destroyers from every conceivable direction. The dark waters of the Java Sea glowed with their phosphorescent wakes. At one point, two torpedoes were reported approaching the Houston to port. The ship then was maneuvering to avoid others; to do more was impossible. Awestruck, my eyes frozen to the onrushing “tin fish,” I braced myself for whatever might come. Then, miracle of miracles, both torpedoes passed directly beneath the Houston without exploding.

As the battle progressed, the evasive maneuvering of both ships and the constant blinding flashes of gunfire made it difficult, and at times impossible, to keep track of the Perth. A few minutes past midnight, she was observed dead in the water and sinking, but with her guns still firing. When Captain Rooks realized that the Perth was finished and escape impossible, he turned the Houston toward the transports, determined to sell his ship dearly. From then on, every ship in the area was an enemy, and we began a savage fight to the death.

The light cruiser HMAS Perth, sunk near Sunda Strait, Java, during the early hours of 1 March 1942 by Japanese naval forces. James C. Fahey Collection, U.S. Naval Institute

The Japanese desperately fought to protect their transports. Like a wolf pack closing in for the kill, destroyers fearlessly raced in close to illuminate the Houston with powerful searchlights so their cruisers’ big guns could find the range. Undaunted by the blinding glare, the Houston’s crew battled back. No sooner were the lights snapped on than our guns blasted them out. One destroyer attempting to illuminate the Houston was torn apart by a main battery salvo, and instantly disappeared. Another, victimized by the port side 5-inch guns, had its bridge shot away. Several times, confused destroyer crews mistakenly illuminated their own transports close to the beach, and the Houston’s gunners quickly seized the opportunity to pump shells into them.

The Houston had no difficulty selecting targets, but the Japanese were hard-pressed at times to distinguish their own ships. On one occasion, we watched in amazement while the enemy, for a short time, fired heavily at each other and no shell so much as splashed near us.

For almost fifty minutes the Houston led a charmed life. The enemy had scored not a single hit of consequence. A salvo of heavy shells had even passed completely through the wardroom, from starboard to port, without exploding. But the Houston’s luck had run its course. A shell, bursting on the forecastle, started a fire in the forward paint locker, pinpointing our location for the enemy. While men of the forward repair party raced to extinguish the fire, Japanese gunners, shooting at point-blank range, scored several more hits on the forecastle. Shrapnel and debris flew in all directions, wounding several in the repair party. It seemed like an eternity, but within a few minutes, the fire was out.

The Houston now was overtaken by the inevitable. At about 0015 the great ship was rocked by a torpedo crashing through the port side. Everyone in the after engine room was killed instantly, and the Houston’s speed was reduced to 23 knots. Thick smoke and hot steam from the engine room inundated the boat deck, driving men from their guns and rendering the after 5-inch gun director useless. When the smoke and steam subsided, gun crews returned to battle stations and fired independently. Power to the shell hoists was knocked out, stopping the flow of 5-inch ammunition from the almost-empty magazines. Men tried to go below to bring shells up by hand, but debris and fires blocked their way. Lacking service ammunition, the crews attacked enemy ships with star shells, all they had left in the ready ammunition boxes.

Close on the heels of the first, a second torpedo smashed into our starboard side, just below the communications deck. Bursting shells started fires throughout the ship, and frantic efforts to extinguish them failed in the face of intensified enemy gunfire. Suddenly number 2 turret, penetrated by a direct hit, blew up sending flames soaring above the bridge. The intense heat buckled steel deck plates, driving everyone out of the conning tower and off the bridge. Communications to other parts of the ship were completely disrupted.

Within a few minutes the fire was out, and turret 2 lay silent and dark. The shortage of ammunition had forced turrets 1 and 2 to use a common magazine. When that was flooded to prevent an explosion, it deprived turret 1 of ammunition. The Houston’s big guns were now silent forever, but a few 5-inch guns, along with the pom-poms, and .50-caliber machine guns continued the fight.

Confident the Houston was finished, the enemy sent in several motor torpedo boats to rake the decks with gunfire. One, caught in the murderous cross fire of the Houston’s .50-caliber machine guns and number 1 pom-pom, disintegrated. Another was sliced in half by the same guns; it sank 50 yards off our port quarter, but not before launching a torpedo, which exploded in the Houston’s guts forward of the quarterback.

The Houston was shipping great quantities of water through gaping holes in her hull and listing slowly to starboard. Her speed fell off making it impossible to maneuver. Ships were attacking from all sides, and enemy planes flew overhead. It was impossible to determine whether we were being blasted by shell, torpedo, or bomb. Like a groggy fighter, the Houston was all but knocked out.

The time had come for Captain Rooks to give his last command. I was standing next to him on the bridge when he summoned the young marine bugler and, in a strong, resolute voice ordered, “Bugler, sound abandon ship.”

As the bugle notes rang out, I decided not to wait to go down the already crowded ladder. Instead, I climbed over the rail and lowered myself to the deck below. This was a fortuitous move, for just as I landed a shell burst on the deck above. I made my way to the starboard catapult tower where, in the gloom, the battered hulk of our last seaplane spread its useless wings. It contained a two-man life raft and a bottle of brandy, both of which I figured would come in handy on such a night. But I was too late. Others were there ahead of me.

About this time, Ensigns Charles D. Smith and Herbert Levitt, looking for wounded shipmates to help over the side, found Captain Rooks lying on the communications bridge. His head and chest were covered with blood. Barely conscious, he was unable to speak. The ensigns gave him a shot of morphine to ease his pain then, seconds later, he died. They covered him with a blanket and were about to abandon ship when, looking back, they saw someone sitting cross-legged on the deck cradling the captain’s body in his arms. They returned to find it was the captain’s rotund Chinese steward, good-naturedly known to all hands as “Buda.” They urged him to leave the sinking ship before it was too late, but he ignored them. Rocking back and forth, he held Captain Rooks as though he were a little boy asleep and, in a voice overburdened with sorrow, repeated over and over, “Captain die, Houston die, Buda die too.” He went down with the ship.

Captain Albert H. Rooks, commanding officer of the heavy cruiser Houston.

Although the Houston continued to be pounded by shells and was sinking slowly, there was no panic or confusion. Men quickly went about the job of abandoning ship. Fear was nowhere apparent, perhaps because the one thing we all had feared most had become a reality.

Enemy ships closed in to rake the weather decks systematically with machine-gun fire. In spite of the order to abandon ship, and the fact that the Houston was plagued with fires and dangerously listing to starboard, a few stouthearted sailors and marines refused to discontinue the battle. Several .50-caliber machine guns, and one 5-inch gun continued to fire. Their diversionary fire served to disrupt the gunning down of many men attempting to get over the side. They undoubtedly saved the lives of shipmates but, in all probability, not their own. Who these heroic men were, will never be known.

I dropped from the catapult tower to the quarterdeck, where several men were sprawled grotesquely. Sadly, I examined each one. I knew them all, and they all were dead. Time was running out. I saw men of the “V” Division struggling to drag a large seaplane pontoon and two wing-tip floats from the starboard hangar. These had been filled with food and water in anticipation of just such an emergency. Joined together in the water as designed, the rig would make a sturdy structure around which we could gather and work out our survival plan. I hurried to help.

We worked fast, for the Houston threatened to capsize at any moment. The heavy float was manhandled out of the hangar while I worked feverishly to take down the starboard lifelines so it could be heaved over the side. I had uncoupled one and was about to break loose the second when, suddenly, the quarterdeck jumped and buckled underfoot. A tremendous geyser of oil and salt water leaped high overhead and pounded back down upon us. The torpedo struck directly below where I was standing, yet I heard no noise. There was no time to reason why.

Until that moment, I had been much too fascinated with the unreality of the nightmare I was living to become frightened. But the torrent of fuel oil and water was for real. It was happening to me, and all I could think of was fire. I had not entertained the thought of being killed or wounded, but this—this was something different. I visualized blazing fuel oil on my body and covering the surface of the sea. I was frantic with the thought that I might not be able to swim through such an inferno. Spontaneously, most of us raced from the starboard side into the dubious shelter of the port hangar. Just as we cleared the quarterdeck, a salvo of shells plowed through it and exploded deep inside the ship.

The fuel oil failed to ignite, but the Houston was listing well over to starboard. With shells slamming into her from all sides, there was only one thing left to do—get the hell off the ship, and the faster the better. I climbed down a cargo net draped over the port side, and dropped into the warm Java Sea. In the dark, with the sounds of combat ringing in my ears, I found myself surrounded by faceless men swimming for their lives. I was sick at heart to hear the anguished cries for help from drowning shipmates, cries to which few, if any, of us could respond. All at once the sea had become an oily battleground where individual men were pitted against death. I thought of the powerful suction created by a sinking ship and swam as hard as I could away from the Houston.

A hundred or more yards astern of my mortally wounded ship, I turned, exhausted and gasping for breath, to witness her last moments. Destroyer searchlights illuminated Houston from bow to stern. She was heeling to starboard, and enemy shells continued to pound into her. I prayed no one on board was still alive. Several heavy shells burst in the water among groups of swimming men. As far removed as I was, the underwater shock waves slammed into my guts like giants fists, making me wince. I shuddered to think of the havoc they inflicted on the poor souls closer to them.

Dazed, unable to believe the macabre scene was real, I floated alone and watched bewitched. The sinking Houston listed further and further to starboard until her yardarms barely dipped into the sea. Even so, the enemy was not yet finished with her. A torpedo, fired by the vindictive foe, exploded amidships on her port side. After having been subjected to so much punishment, the ship should have capsized instantly. Instead, the Houston tediously rolled back on an even keel. With decks awash, the proud ship paused majestically, while a sudden breeze picked up the Stars and Stripes, still firmly two-blocked on her mainmast, and waved them in one last defiant gesture. Then, with a tired shudder, the magnificent Houston vanished beneath the Java Sea.

*Helfrich relieved Admiral Thomas S. Hart as commander, ABDAFLOAT, on 14 February 1942.

*Unknown to Doorman, he was leading the Allied ships into a newly laid minefield. The Jupiter was sunk by one of those mines.