TWO

What a Plant Smells

Stones have been known to move and trees to speak.

—Shakespeare, Macbeth

Plants smell. Plants obviously emit odors that animals and human beings are attracted to, but they also sense their own odors and those of neighboring plants. Plants know when their fruit is ripe, when their neighbor has been cut by a gardener’s shears, or when their neighbor is being eaten by a ravenous bug; they smell it. Some plants can even differentiate the smell of a tomato from the smell of wheat. Unlike the large spectrum of visual input that a plant experiences, a plant’s range for smell is limited, but it is highly sensitive and communicates a great deal of information to the living organism.

If you look up the word “smell” in a standard dictionary today, you’ll see that it is defined as the ability “to perceive odor or scent through stimuli affecting the olfactory nerves.” Olfactory nerves can easily be understood as the nerves that connect the smell receptors in the nose to the brain. In olfaction, the stimuli are small molecules dissolved in the air. Human olfaction involves the cells in our nose that receive airborne chemicals, and it involves our brain, which processes this information so that we can respond to various smells. If you open a bottle of Chanel No5 on one side of a room, for example, you smell it on the other because certain chemicals evaporate from the perfume and disperse across the room. The molecules are present in very dilute quantities, but our noses are filled with thousands of receptors that react specifically with different chemicals. It only takes one molecule to connect with a receptor to sense the new smell.

Our body’s mechanism for the perception of smells is different from the mechanism involved in the perception of light. As we saw in the previous chapter, we only need four classes of photoreceptors that differentiate between red, green, blue, and white to see the colors of a complete palette. When it comes to olfaction, however, we have hundreds of different receptor types, each specifically designated for a unique volatile chemical.

The way that a smell receptor in the nose binds to a chemical is similar to the concept of a lock-and-key system. Each chemical has its own particular shape that fits into a specific protein receptor, just as each key has its own particular structure that fits into a specific lock. Only a unique chemical can bind to a unique receptor, and once this happens, it initiates a cascade of signals that ends in a nerve firing in the brain to let us know that the receptor has been stimulated. We interpret this as a particular smell. Scientists have recorded hundreds of individual aroma chemicals such as menthol (the major component of aroma in peppermint) and putrescine (responsible for the foul-smelling aroma that emanates from dead flesh). But any particular aroma we smell is usually the result of a mix of several chemicals. For example, while about half of the peppermint odor is due to menthol, the rest is a combination of more than thirty other chemicals. That’s why we can describe the bouquet of an excellent spaghetti sauce, or of a deep red wine, or of a newborn baby in so many different ways.

So what happens in a plant? Our dictionary’s definition of “smell” excludes plants from the discussion. They are removed from our traditional understandings of the olfactory world because they do not have a nervous system, and olfaction for a plant is obviously a nose-less process. But let’s say we tweak this definition to “the ability to perceive odor or scent through stimuli.” Plants are indeed more than remedial smellers. What odors does a plant perceive, and how do smells influence a plant’s behavior?

Unexplained Phenomena

My grandmother didn’t study plant biology or agriculture. She didn’t even finish high school. But she knew that she could get a hard avocado to soften by putting it in a brown paper bag with a ripe banana. She learned this magic from her mother, who learned it from her mother, and so on. In fact, this practice goes back to antiquity, and ancient cultures had diverse methods for getting fruit to ripen. The ancient Egyptians slashed open a few figs in order to get an entire bunch to ripen, and in ancient China people would burn ritual incense in a storage room of pears to get the fruit to ripen.

In the early twentieth century, farmers in Florida would ripen citrus in sheds heated by kerosene. These farmers were sure that the heat induced the ripening, and of course their conclusion sounds logical. You can imagine their dismay, then, when they plugged in some electric heaters near the citrus and found that the fruit didn’t cooperate at all. So if it wasn’t the heat, could the ripening magic be coming from the kerosene?

It turned out that it was. In 1924, Frank E. Denny, a scientist from the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Los Angeles, demonstrated that kerosene smoke contains minute amounts of a molecule called ethylene and that treating any fruit with pure ethylene gas is enough to induce ripening. The lemons he studied were so sensitive to ethylene that they could respond to a tiny amount in the air, at a ratio of 1 to 100 million. Similarly, it turns out that the smoke from the Chinese incense also contained ethylene. So a simple scientific model would posit that the fruit “smells” minuscule amounts of ethylene in the smoke and translates this smell into rapid ripening. We smell the smoke from a neighbor’s barbecue, and we salivate; a plant detects some ethylene in the air, and it softens up.

But this explanation doesn’t answer two important questions: First, why do plants respond to the ethylene in smoke anyway? And second, what about my grandma putting two fruits together in a bag and the Egyptians slashing their figs? Experiments carried out by Richard Gane in Cambridge in the 1930s point to some answers. Gane analyzed the air immediately surrounding ripening apples and showed that it contained ethylene. A year after his pioneering work, a group at the Boyce Thompson Institute at Cornell University proposed that ethylene is the universal plant hormone responsible for fruit ripening. In fact, numerous subsequent studies have revealed that all fruits, including figs, emit this organic compound. So it’s not just smoke that contains ethylene; normal fruit emits this gas as well. When the Egyptians slashed their figs, they allowed the ethylene gas to easily escape. When we put a ripe banana in a bag with a hard pear, for example, the banana gives off ethylene, which is “smelled” by the pear, and the pear quickly ripens. The two fruits are communicating their physical states to each other.

Ethylene signaling between fruits didn’t evolve so that we can have perfectly ripe pears whenever we crave them, of course. Instead, this hormone evolved as a regulator of plant responses to environmental stresses such as drought and wounding and is produced naturally throughout the life cycle of all plants (including little mosses). But ethylene is particularly important for plant aging as it is the major regulator of leaf senescence (the aging process that produces autumn foliage) and is produced in copious amounts in ripening fruit. The ethylene produced in ripening apples ensures not only that the entire fruit ripens uniformly but that neighboring apples will also ripen, which will give off even more ethylene, leading to an ethylene-induced ripening cascade of McIntoshes. From an ecological perspective, this has an advantage in ensuring seed dispersal as well. Animals are attracted to “ready-to-eat” fruits like peaches and berries. A full display of soft fruits brought on by the ethylene-induced wave guarantees an easily identifiable market for animals, which then disperse the seeds as they go about their daily business.

Finding Food

Cuscuta pentagona is not your normal plant. It’s a spindly orange vine that can grow up to three feet high, produces tiny white flowers of five petals, and is found all over North America. What’s unique about Cuscuta is that it has no leaves and it isn’t green because it lacks chlorophyll, the pigment that absorbs solar energy, which allows plants to turn light into sugars and oxygen through photosynthesis. Cuscuta obviously can’t carry out photosynthesis, as most plants do, so it doesn’t make its own food from light. With all of this in mind, we’d assume Cuscuta would starve, but instead it thrives. Cuscuta lives in another way: it gets its food from its neighbors. It is a parasitic plant. In order to live, Cuscuta attaches itself to a host plant and sucks out the nutrients provided by the host by burrowing an appendage into the plant’s vascular system. Not surprisingly, Cuscuta, commonly known as the dodder plant, is an agricultural nuisance and is even classified as a “noxious weed” by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But what makes Cuscuta truly fascinating is that it has culinary preferences: it chooses which neighbors to attack.

Five-angled dodder (Cuscuta pentagona)

Before we get to the reasons why Cuscuta has very specific and refined culinary tastes, let’s see how it starts its parasitical life. Cuscuta seeds germinate like any other plant seeds. Placed on soil, the seed breaks open, the new shoot grows into the air, and the new root burrows into the dirt. But a young dodder left on its own will die if it doesn’t quickly find a host to live off of. As a dodder seedling grows, it moves its shoot tip in small circles, probing the surroundings the way we do with our hands when we’re blindfolded or searching for the kitchen light in the middle of the night. While these movements seem random at first, if the dodder is next to another plant (say, a tomato), it’s quickly obvious that the Cuscuta is bending and growing and rotating in the direction of the tomato plant that will provide it with food. The dodder bends and grows and rotates until finally it finds a tomato leaf. But rather than touch the leaf, the dodder sinks down and keeps moving until it finds the stem of the tomato plant. In a final act of victory, it twirls itself around the stem, sends microprojections into the tomato’s phloem (the vessels that carry the plant’s sugary sap), and starts siphoning off sugars so that it can keep growing and eventually flower. Oh, and the tomato plant starts to wilt as the dodder thrives.

Dr. Consuelo De Moraes even documented this behavior on film.* She is an entomologist at Penn State University whose main interest is understanding volatile chemical signaling between insects and plants, and between plants themselves. One of her projects centered on figuring out how Cuscuta locates its prey. She demonstrated that the dodder vines never grow toward empty pots or pots with fake plants in them but faithfully grow toward tomato plants no matter where she put them—in the light, in the shade, wherever. De Moraes hypothesized that the dodder actually smelled the tomato. To check her hypothesis, she and her students put the dodder in a pot in a closed box and put the tomato in a second closed box. The two boxes were connected by a tube that entered the dodder’s box on one side, which allowed the free flow of air between the boxes. The isolated dodder always grew toward the tube, suggesting that the tomato plant was giving off an odor that wafted through the tube into the dodder’s box and that the dodder liked it.

(* To fully appreciate this, you really have to see it with your own eyes: www.youtube.com/watch?v=NDMXvwa0D9E.)

If the Cuscuta was really going after the smell of the tomato, then perhaps De Moraes could just make a tomato perfume and see if the dodder would go for that. She created an eau de tomato stem extract that she placed on cotton swabs and then put the swabs on sticks in pots next to the Cuscuta. As a control, she put some of the solvents that she used to make the tomato perfume on other swabs of cotton and put these on sticks next to the Cuscuta as well. As predicted, she tricked the dodder into growing toward the cotton giving off the tomato smell, thinking it was going to find food, but not to the cotton with the solvents.

Clearly, the dodder can smell a plant to find food. But as I explained earlier, this noxious weed has its preferences. Given a choice between a tomato and some wheat, the dodder will choose the tomato. If you grow your dodder in a spot that is equidistant between two pots—one containing wheat, the other containing tomato—the dodder will go for the tomato. Even at the level of fragrance, and not the whole plant, dodder prefers eau de tomato to eau de wheat.

At the basic chemical level, eau de tomato and eau de wheat are rather similar. Both contain beta-myrcene, a volatile compound (one of the hundreds of unique chemical smells known) that on its own can induce Cuscuta to grow toward it. So why the preference? One clear hypothesis is the complexity of the bouquet. In addition to beta-myrcene, the tomato gives off two other volatile chemicals that the dodder is attracted to, making for an overall irresistible dodder-attracting fragrance. Wheat, however, only contains one dodder-enticing odor, the beta-myrcene, and not the other two found in the tomato. What’s more, wheat not only makes fewer attractants but also makes (Z)-3-Hexenyl acetate, which repels the dodder more than the beta-myrcene attracts it. In fact, the Cuscuta grows away from (Z)-3-Hexenyl acetate, finding the wheat simply repulsive.

(L)eavesdropping

In 1983, two teams of scientists published astonishing findings related to plant communication that revolutionized our understanding of everything from the willow tree to the lima bean. The scientists claimed that trees warn each other of imminent leaf-eating-insect attack. The results were relatively straightforward; the implications astounding. News of their work soon spread to popular culture, with the idea of “talking trees” found in the pages not only of Science but of mainstream newspapers around the world.

David Rhoades and Gordon Orians, two scientists from the University of Washington, noticed that caterpillars were less likely to forage on leaves from willow trees if these trees neighbored other willows already infested with tent caterpillars. The healthy trees neighboring the infested trees were resistant to the caterpillars because, as Rhoades discovered, the leaves of the resistant trees, but not of susceptible ones isolated from the infested trees, contained phenolic and tannic chemicals that made them unpalatable to the insects. As the scientists could detect no physical connections between the damaged trees and their healthy neighbors—they did not share common roots, and their branches did not touch—Rhoades proposed that the attacked trees must be sending an airborne pheromonal message to the healthy trees. In other words, the infested trees signaled to the neighboring healthy trees, “Beware! Defend yourselves!”

White willow (Salix alba)

Just three months later, the Dartmouth researchers Ian Baldwin and Jack Schultz published a seminal paper that supported the Rhoades report. Baldwin and Schultz had been in contact with Rhoades and designed their experiment to be carried out under very controlled conditions, rather than monitoring trees grown open in nature, as Rhoades and Orians had done. They studied poplar and sugar maple seedlings (about a foot tall) grown in airtight Plexiglas cages. They used two cages for their experiment. The first contained two populations of trees: fifteen trees that had two leaves torn in half, and fifteen trees that were not damaged. The second cage contained the control trees, which of course were not damaged. Two days later, the remaining leaves on the damaged trees contained increased levels of a number of chemicals, including toxic phenolic and tannic compounds that are known to inhibit the growth of caterpillars. The trees in the control cage didn’t show increases in any of these compounds. The important result here was that the leaves of the intact trees in the same cage as the damaged ones also showed large increases in phenolic and tannic compounds. Baldwin and Schultz proposed that the damaged leaves, whether by tearing as in their experiments or by insect feeding as in Rhoades’s observations of the willow trees, emitted a gaseous signal that enabled the damaged trees to communicate with the undamaged ones, which resulted in the latter defending themselves against imminent insect attack.

White poplar (Populus alba)

These early reports of plant signaling were often dismissed by other individuals in the scientific community as lacking the correct controls or as having correct results but exaggerated implications. At the same time, the popular press embraced the idea of “talking trees” and anthropomorphized the conclusions of the researchers. Whether it was the Los Angeles Times or The Windsor Star in Canada or The Age in Australia, news outlets went berserk over the idea and carried stories with titles like “Scientists Turn New Leaf, Find Trees Can Talk” and “Shhh. Little Plants Have Big Ears,” and the front page of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune bore the headline “Trees Talk, Respond to Each Other, Scientists Believe.” The New York Times even titled its main editorial on June 7, 1983, “When Trees Talk,” in which the writer speculated about “talking trees whose bark is worse than their blight.” All this public attention didn’t help convince scientists to adopt the ideas of chemical communication being posited by Baldwin and his colleagues. But over the past decade, the phenomenon of plant communication through smell has been shown again and again for a large number of plants, including barley, sagebrush, and alder, and Baldwin, a young chemist just barely out of college at the time of the original publication, has gone on to a prominent scientific career.*

(* Baldwin now directs the Department of Molecular Ecology at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany.)

While the phenomenon of plants being influenced by their neighbors through airborne chemical signals is now an accepted scientific paradigm, the question remains: Are plants truly communicating with each other (in other words, purposely warning each other of approaching danger), or are the healthy ones just eavesdropping on a soliloquy by the infested plants, which do not intend to be heard? When a plant releases a smell in the air, is it a form of talking, or is it, so to say, just passing gas? While the idea of a plant calling out for help and warning its neighbors has allegorical and anthropomorphic beauty, does it really reflect the original intent of the signal?

Martin Heil and his team at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies in Irapuato, Mexico, have been studying wild lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus) for the past several years to further explore this question. Heil knew that when a lima bean plant is eaten by beetles, it responds in two ways. The leaves that are being eaten by the insects release a mixture of volatile chemicals into the air, and the flowers (though not directly attacked by the beetles) produce a nectar that attracts beetle-eating arthropods.* Early in his career at the turn of the millennium, Heil had worked at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Germany, the same institute where Baldwin was (and still is) a director, and like Baldwin before him Heil wondered why it was that lima beans emitted these chemicals.

(* Many insect-eating arthropods have coevolved with plants and recognize the volatile signals emitted by herbivore-attacked plants and use this signal as a food-finding cue.)

Heil and his colleagues placed lima bean plants that had been attacked by beetles next to plants that had been isolated from the beetles and monitored the air around different leaves. They chose a total of four leaves from three different plants: from a single plant that had been attacked by beetles they chose two leaves, one leaf that had been eaten and another that was not; a leaf from a neighboring but healthy “uninfested” plant; and a leaf from a plant that had been kept isolated from any contact with beetles or infested plants. They identified the volatile chemical in the air surrounding each leaf using an advanced technique known as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (often featured on the show CSI and employed by perfume companies when they are developing a new fragrance).

Wild lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus)

Heil found that the air emitted from the foraged and the healthy leaves on the same plant contained essentially identical volatile chemicals, while the air around the control leaf was clear of these gases. In addition, the air around the healthy leaves from the lima beans that neighbored beetle-infested plants also contained the same volatiles as those detected from the foraged plants. The healthy plants were also less likely to be eaten by beetles.

In this set of experiments, Heil confirmed the earlier studies by showing that the proximity of the undamaged leaves to the attacked leaves provided them with a defensive advantage against the insects. But Heil was not convinced that damaged plants “talk” to other plants to warn them against impending attack. Rather, he proposed that the neighboring plant must be practicing a form of olfactory eavesdropping on an internal signal actually intended for other leaves on the same plant.

Heil modified his experimental setup in a simple, albeit ingenious, way to test his hypothesis. He kept the two plants next to each other but enclosed the attacked leaves in plastic bags for twenty-four hours. When he checked the same four types of leaves as in the first experiment, the results were different. While the attacked leaf continued to emit the same chemical as it did before, the other leaves on the same vine and neighboring vines now resembled the control plant; the air around the leaves was clear.

Heil and his team opened the bag around the attacked leaf, and with the help of a small ventilator that’s usually used on tiny microchips to help cool computers, they blew the air in one of two directions: either toward the neighboring leaves farther up the vine or away from the vine and into the open. They checked the gases coming out of the leaves higher up the stem and measured how much nectar they produced. The leaves blown with air coming from the attacked leaf started to emit the same gases themselves, and they also produced nectar, while the leaves that were not exposed to the air from the attacked leaf remained the same.

The results were significant because they revealed that the gases emitted from an attacked leaf are necessary for the same plant to protect its other leaves from future attacks. In other words, when a leaf is attacked by an insect or by bacteria, it releases odors that warn its brother leaves to protect themselves against imminent attack, similar to guard towers on the Great Wall of China lighting fires to warn of an oncoming assault. In this way, the plant ensures its own survival as leaves that have “smelled” the gases given off by the attacked leaves will be more resistant to the impending onslaught.

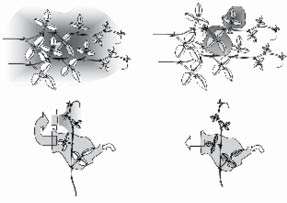

An illustration of Heil’s experiments. On the top two panels Heil let beetles attack the gray leaves and then checked the air around other leaves on both the same vine and the neighboring vine. On the top left we see that the air around all the leaves of both vines contained the same chemicals, while on the top right, when Heil isolated the attacked leaves in plastic bags, the air around them was different from the air around all the other leaves on both vines. On the bottom we see his second experiment. Heil blew air from attacked leaves either onto other leaves on the same vine (on the left) or away from the other leaves (the bottom right panel).

So what about the neighboring plant? If it’s close enough to the attacked plant, then it benefits from this internal “conversation” among leaves on the infested plant. The neighboring plant eavesdrops on a nearby olfactory conversation, which gives it essential information to help protect itself. In nature, this olfactory signal persists for at least a few feet (different volatile signals, depending on their chemical properties, travel for shorter or much longer distances). For lima beans, which naturally enjoy crowding, this is more than enough to ensure that if one plant is in trouble, its neighbors will know about it.

What exactly is the lima bean smelling when its neighbor is eaten? Eau de lima, just like the eau de tomato described in the dodder experiment, is a complex mixture of aromas. In 2009, Heil collaborated with colleagues from South Korea and analyzed the different volatile compounds emitted from the leaves of the attacked plants in order to identify the chemical messenger. But the trick was identifying the one chemical responsible for the evident communication with other leaves. They compared the compounds emitted by leaves following bacterial infection with those emitted following an insect feeding. Both treatments resulted in the expression of similar volatile gases, except for two gases that discriminated between the two treatments. The leaves under bacterial attack emitted a gas called methyl salicylate, and those eaten by bugs did not; the latter produced a gas called methyl jasmonate.

Methyl salicylate is very similar in structure to salicylic acid. Salicylic acid is found in copious amounts in the bark of willow trees. In fact, the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates described a bitter substance, now known to be salicylic acid, from willow bark that could ease aches and reduce fevers. Other cultures in the ancient Middle East also used willow bark as a medicine, as did Native Americans. Centuries later, we know salicylic acid as the chemical precursor for aspirin (which is acetylsalicylic acid), and salicylic acid itself is a key ingredient in many modern antiacne face washes.

Although willow is a well-known producer of salicylic acid, which has been extracted from this tree for years, all plants produce this chemical in various amounts. They also produce methyl salicylate (which by the way is an important ingredient in Bengay ointment). But why would a plant produce a pain reliever and fever reducer? As with any phytochemical (or plant-produced chemical), plants don’t make salicylic acid for our benefit. For plants, salicylic acid is a “defense hormone” that potentiates the plant’s immune system. Plants produce it when they’ve been attacked by bacteria or viruses. Salicylic acid is soluble and released at the exact spot of infection to signal through the veins to the rest of the plant that bacteria are on the loose. The healthy parts of the plant respond by initiating a number of steps that either kill the bacteria or, at the very least, stop the plague’s spread. Some of these include putting up a barrier of dead cells around the site of infection, which blocks the movement of the bacteria to other parts of the plant. You sometimes see these barriers on leaves; they appear as white spots. These spots are areas of the leaf where cells have literally killed themselves so that the bacteria near them can’t spread farther.

At a broad level, salicylic acid serves similar functions in both plants and people. Plants use salicylic acid to help ward off infection (in other words, when they’re sick). We’ve used salicylic acid since ancient times, and we use the modern derivative of aspirin when we’re sick with an infection that causes aches and pains.

Returning to Heil’s experiments: his lima beans emitted methyl salicylate, a volatile form of salicylic acid, after they were attacked with bacteria. This result supported work done a decade earlier in the lab of Ilya Raskin at Rutgers University, who had shown that methyl salicylate was the major volatile compound produced by tobacco following viral infection. Plants can convert soluble salicylic acid to volatile methyl salicylate and vice versa. One way to understand the difference between salicylic acid and methyl salicylate is this: plants taste salicylic acid, and they smell methyl salicylate. (As we know, taste and smell are interrelated senses. The major difference is that we taste soluble molecules on the tongue, while we smell volatile molecules in the nose.)

By enclosing the infected leaves in plastic bags, Heil had blocked the methyl salicylate from wafting from the infected leaf to the noninfected one, whether on the same vine or on a neighboring plant. When the noninfected leaf finally smelled the methyl salicylate by having the air from the infected leaf blown onto it, it inhaled the gases through the tiny openings on the leaf surface (called stomata). Once deep in the leaf, the methyl salicylate was converted back to salicylic acid, which, as we now know, plants take when they’re feeling sick.*

(* If you’re wondering about methyl jasmonate, the story is quite similar. Methyl jasmonate is a voluble form of jasmonic acid, a defense hormone that plants emit upon leaf damage inflicted by herbivorous creatures.)

Corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum)

Do Plants Smell?

Plants give off a literal bouquet of smells. Imagine the smell of roses when you walk on a garden path in the summertime, or of freshly cut grass in the late spring, or of jasmine blooming at night. How about the sweet pungent odor of a brown banana intemingled with the myriad of smells at a farmers’ market? Without looking, we know when fruit is ready to eat, and no visitor to a botanical garden can be oblivious to the offensive odor of the world’s largest (and smelliest) flower, the Amorphophallus titanum, better known as the corpse flower. (Luckily, it blooms only once every few years.)

Many of these aromas are used in complex communication between plants and animals. The smells induce different pollinators to visit flowers and seed spreaders to visit fruits, and as the author Michael Pollan infers, these aromas can even induce people to spread flowers all over the world. But plants don’t just give off odors; as we’ve seen, they undoubtedly smell other plants.

Of course, like plants, we sense airborne volatile compounds. We use our noses to get a whiff of many things, particularly food. But we need to remember that “olfaction” means much more than smelling good food. Our language is littered with olfactory-tainted statements like “the smell of fear” and “I smell trouble,” and smells are intimately tied with memory and emotion. The olfactory receptors in our noses are directly connected to the limbic system (the control center for emotion) and evolutionarily to the most ancient part of our brains. Like plants, we communicate via pheromones, though we’re often not aware of it.

Pheromones are given off by one individual and trigger a social response in another. Pheromones in different animals, from flies to baboons, communicate various situations: social dominance, sexual receptiveness, fear, and so on. We also are influenced by odors and emit odors that affect those around us. For example, synchronization of menstrual cycles among women living in close quarters has been found to be due to odor cues in perspiration. A recent (and provocative) study in Science showed that men who simply sniffed negative-emotion-related odorless tears obtained from women showed reduced levels of testosterone and reductions in sexual arousal. So subtle olfactory signals could potentially affect many aspects of our psyche.

Plants and animals sense volatile compounds in the air, but can this really be considered olfaction by plants? Plants obviously don’t have olfactory nerves that connect to a brain that interprets the signals, and as of 2011 only one receptor for a volatile chemical, the ethylene receptor, has been identified in plants. But ripening fruits, Cuscuta, Heil’s plants, and other flora throughout our natural world respond to pheromones, just as we do. Plants detect a volatile chemical in the air, and they convert this signal (albeit nerve-free) into a physiological response. Surely this could be considered olfaction.

So if plants can “smell” in their own unique ways without olfactory nerves, is it possible they can “feel” as well without sensory nerves?