ONE

THE GOLDEN ARROW

THE ABSENT SEA

The railways operating from the south London termini are disappointing to the railway romantic for many reasons. The trains are uninspiring: stubby, overlit electrical ‘units’ in ahistorical liveries. There are relentless, robotic announcements, and too much catering on the station concourses, where you don’t want it, and not enough on the trains, where you do.

And there are no long-distance expresses. Generally speaking, there isn’t room for the southern operators to stretch out, and there never has been. Yes, the London & South Western Railway did reach as far as Padstow from its base at Waterloo – much to the irritation of the Great Western, which regarded Cornwall as its own backyard – but that was a freakish bit of outreach.

There was self-consciousness about this among the southern companies, which would be amalgamated into the company called Southern in the railway grouping of 1923. Whether we’re talking about the above-mentioned LBSCR and LSWR, the South Eastern Railway, or the London, Chatham & Dover, none dared claim the prefix ‘Great’, unlike the Great Western, the Great Northern or the Great Central. But while the southern trains may not have travelled over long distances, they could take a running jump at the sea. They could operate trains that connected with boats: ‘boat trains’ in fact, and these could be the first leg in the longest journeys of all.

By the 1840s the Channel ports were linked to London by rail, and the French ports were linked to Paris. A journey from London to Paris took eleven and a half hours in 1851. This was down to six and a half hours by 1913, when faster trains and faster steamers (propeller, as opposed to paddle-driven) had opened up the Continent. It is estimated that 150,000 Britons crossed the Channel or North Sea in 1850; in 1913 it was more like 2 million.

At Victoria today there are few signs of the days of the boat train, when the station proclaimed itself ‘The Gateway to the Continent’. Yes, there is a bureau de change, and the left luggage office is subtitled ‘consigne’, but these facilities are mainly for passengers to Gatwick Airport.

Victoria station used to bristle with inducements to foreign travel, and images of boats and the sea. Today there is only one boat at Victoria. It is on a pretty, tiled map located in an alcove off one of the entrances to the station from Victoria Place. The map is opposite a South African deli called Savanna, which is built into what used to be the booking office of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway. Because the map is in a quiet alcove, somebody is usually making a mobile phone call right in front of it, and you have to ask them to step aside, at which point they will notice the map for the first time, and be amazed and appalled at your interest in it. At the top of the map are gold letters on a semicircular blue mosaic: ‘LB & SCR Ry. Map of System.’ The map shows the lines of the railway stretching south of London ‘showing all important landmarks’: in other words, ‘Stations, Motor Halts, Golf Links, Race Courses, Harbours for Yachts, Military Stations and Castles.’

At the bottom is the sea, and dotted lines showing London, Brighton & South Coast Railway boat-train connections from Portsmouth to the Isle of Wight, and from Newhaven to Dieppe, Bordeaux, La Rochelle and St Nazaire. At the very bottom is a small vertical sailing ship, apparently tumbling off the edge of the world. It is odd that this one remaining ship at Victoria should be associated with the LBSCR, and for the following reason …

Victoria used to be two stations. Anyone who doesn’t know this, must think it a very bizarre design indeed, what with the two different façades and the brick wall dividing Platforms 1 to 8 from Platforms 9 to 19. One side was owned by the London, Chatham & Dover Railway, the other by the LBSCR. Older staff at the station still refer to ‘the eastern side’ (Platforms 1 to 8) and ‘the central side’ (9 to 19). The tile map is on the central, or LBSCR, side. It was put up by that company when it redeveloped its half of the station in 1906, employing a pleasing, airy Art Nouveau style. It is ironic that the one remaining ship at Victoria should be on that side because, as we will be seeing in the next chapter, the LBSCR was mainly concerned with ensnaring commuters rather than operating boat trains.

The other tenant of Victoria, the London, Chatham & Dover, was the more seagoing railway, being one of two companies (we will meet the other in a minute) serving Dover and Folkestone. In 1907 the LCDR rebuilt its own half of Victoria. In London’s Termini Alan A. Jackson writes: ‘a handsome four-storey masonry block rose up. The style was French Second Empire, with a maritime flavour bestowed by four mermaids contemplating their well-parted bosoms.’ Let’s get it straight about the bosoms. You can see both nipples on the four mermaids on the LCDR side, whereas you can only see half of one breast belonging to the one mermaid on the LBSCR side.

The canopy in front of the LCDR side boasted ‘Shortest and Quickest Route to Paris & Continent – Sea Passage One Hour’. The Brighton side countered with ‘To Paris and the Continent via Newhaven and Dieppe – Shortest and Cheapest Route’. In the case of the Brighton side, ‘Shortest Route’ meant ‘shortest to Dieppe’ rather than Paris. But it certainly was the cheapest route, for the very good reason that Newhaven–Dieppe took three and a half hours – which on the steamers of the time meant three and a half hours of being sick – as against one hour from Dover to Calais. (Incidentally, modern ferries serving those routes take slightly longer. Cynics say the trip is prolonged so people will spend more in the on-board shops.)

The LCDR side boasted more numerous destinations, ranging from Crystal Palace to (rather vaguely) ‘India’. If you go to Blackfriars – built as the City terminus of the same company and recently rebuilt – you will see a monument resembling a wall of paving stones, each inscribed with the name of a destination theoretically reachable by the LCDR. Dresden jostles with Faversham, Chatham with Lucerne, Berlin with Bickley. This sort of grandiosity had been satirised as early as 1839 by Angus B. Reach in A Comic Bradshaw. He lists the destinations of the fictional ‘Eastern Countries Line’. The train leaves Shoreditch at 6; it arrives at Bow at half a minute past six. It then goes to Constantinople, Aleppo, Jericho, Baghdad, Canton, Peking.

To be clear, the LCDR trains, whether from Victoria or Blackfriars, went no further south than Dover. You would have had to change several times to get to Lucerne, and many more to reach India.

France was always the main destination. Cheap excursions to France were widely available by Edwardian times, and the newly formed Workmen’s Travelling Club suggested that a week in Paris could cost ‘less than a week at Margate’. A weekend return ticket to Paris could be had for a pound (the weekly wage of the very lowest earners), and foreign hotels were cheaper than British ones. But there was also a big luxury market.

In 1889 both the London Chatham & Dover Railway and the South Eastern Railway – which was based at Charing Cross – put on luxury trains to Paris via Dover–Calais, to coincide with the Paris International Exhibition of that year. They were known as the Club Trains, and these two trains corresponded to a single French train – operated by the Nord company – that collected passengers from Calais and took them on to Paris. On the British side the services exemplify the absurdity of a free market in railways. The LCDR, based at Victoria, ran its Dover trains over its main line via Chatham and Canterbury. This was called going ‘up Chatham’. The South Eastern, based at Charing Cross, ran its Dover trains over its own main line, via Orpington and Ashford. (The lines, and sometimes the Club Trains themselves – which left their respective stations at 4.15 p.m. – crossed at Chislehurst.) In other words, the LCDR approached Dover from the east, while the South Eastern approached it from the west, even though the point of origin of the LCDR (Victoria) was west of that of the South Eastern (Charing Cross).

The two lines, and the two trains, converged again on windswept Admiralty Pier at Dover. Back then, as today, there were always plenty of bored fishermen on Admiralty Pier, and they would make bets on which company’s train would arrive first. But it didn’t really matter (except to the fishermen), because the two sets of passengers were destined to board the same steamer, which awaited, bucking about on its moorings. As the passengers queued to board, a boy with a barrow offered hot coffee or soup.

The club trains were not great successes and were withdrawn in 1893, although each company continued to operate several Paris trains a day, most including Pullman carriages. In 1899 the South Eastern and the Chatham companies saw sense and pooled their assets. They didn’t formally merge but began operating jointly as the South East & Chatham Railway. Their two main lines were joined by means of the ‘Chislehurst Loops’ at Chislehurst, where they had crossed. The preferred route for the boat trains was from Charing Cross to Folkestone and Dover along the old SER main line, via Tonbridge and Ashford. This was flatter than the Chatham route or, as the railway surveyors say, ‘less graded’.

After the First World War the old SER route remained the preferred option for boat trains, but Victoria became the favoured starting-point, since it had more and longer platforms. Charing Cross dwindled towards being a commuter-only station, and the traditional boast of the hotel became all too true: ‘Acknowledged one of the quietest hotels in the West End.’

In the railway grouping of 1923 the companies using the southern termini were collected under one head as the Southern Railway. Its boat-train services were listed in its Continental Handbook, which began with a quotation from Henry VI Part One, Act V, scene i: ‘See them guarded and safely brought to Dover;/Where, inshipped, commit them to the fortunes of the sea.’ The book would make a Phileas Fogg of any reader. Hundreds of destinations were listed, and the fold-out map showed international routes such as ‘London – China–Japan by the Trans-Siberian Rly’.

Here, apparently, was the high point of the boat train era, but a shadow loomed over the cross-Channel business. In 1922 the first scheduled air services between London and Paris had begun. Meanwhile there were complaints from the users of luxury boat trains that the trains weren’t quite luxurious enough. The delays in the customs sheds at Dover were too long; the Channel boats were overcrowded. There was a desire for a smoother, more coherent journey.

Whereas some of the Paris-bound boat trains had incorporated one or two Pullman coaches, in 1924 the Southern met the demand for greater pampering with the first all-Pullman boat train. It ran from Victoria to Dover, and it was nicknamed ‘the White Pullman’. The train ran in what had become the standard Pullman livery of umber and ivory, and ‘white’ referred to the ivory part. This whiteness was deemed worthy of comment because the South East, Chatham & Dover Railway (which had been operating to Dover until the grouping of the year before) had been unique in running its Pullmans in its own ‘crimson-lake’ livery.

In 1929 this train was formally named the Golden Arrow.

The inaugural run of the Arrow took place at eleven o’clock on 15 May 1929. The single fare, including supplement, was £6 10s., or about £260 in today’s money. At the time of writing the most expensive single first-class (or ‘Business Premier’) fare between London and Paris on Eurostar is £276. After a steady decline that will be described later, the Arrow ran for the last time on 30 September 1972.

The train was the brainchild of Davison Dalziel, chairman of the International Sleeping Car Company, known for short as Wagons-Lits. This operated such famous continental trains as the Train Bleu and the Orient Express, and it had a close relationship with the Pullman company. John Elliot of the Southern – that pioneering PR man mentioned in the introduction – was all in favour. ‘It was the number one train for us’, he wrote.

4. The Golden Arrow at Dover in 1948. It runs under the walkway that leads to Admiralty Pier. The Lord Warden Hotel (as was) is in the background. The engine is Boscastle of the West Country class.

Like the White Pullman, the Arrow was all first-class Pullman. It was a long steam train operating amid the many electrical pygmies of the Southern. Until 1961 it was hauled by a succession of big locomotives. From inception until 1939 these were of the King Arthur or Lord Nelson classes. After the war bigger locomotives still were used: engines of the Battle of Britain, Merchant Navy and Britannia classes. On their smoke-box doors the engines sported a golden arrow, pointing diagonally down to the right, and the Arrow was advertised by posters showing the train inhabiting a thunderbolt pointing in that direction.

The Arrow was a long-distance express, taking the record time of six hours thirty-five minutes to reach Paris. It left Victoria at 11 a.m. and arrived at Paris at 5.35 p.m. But it was a long-distance train only by virtue of its being two trains. You had to add together the Golden Arrow strictly speaking (London–Dover) with the French counterpart, which was called, with pleasing reciprocity, the Flèche d’Or (Golden Arrow in French), its own luxury carriages supplied by Wagons-Lits. The Flèche d’Or collected the passengers from Calais and took them on to Paris. In between came the steamer (never to be called a mere ‘ferry’), a luxury vessel called SS Canterbury, whose only job was to carry Arrow passengers. In the pious business-speak of today, it would be called a ‘dedicated service’. Other than for boarding and disembarking from the steamer, there were no stops, or no ‘station stops’ in the modern parlance. And the whole thing happened in reverse, the Flèche d’Or leaving Paris at noon, France being an hour ahead. Passports and hand luggage were examined on the train; bigger luggage was examined before it was put into the baggage wagon. So Arrow passengers could be ‘waved through’ the customs shed at Dover.

The Arrow was the golden train of the Golden Age. In his memoir John Elliot writes, ‘I well remember the inauguration party on the day of the initial run.’ He doesn’t actually give much detail about it, except to say that ‘Javary, Director-General of the Nord Railway’ was present; also Viscount Churchill, although why he was there Elliot couldn’t think, since he was a director of the Great Western Railway. Lord Churchill’s better-known relation Winston was to become a regular on the service, and Elliot writes that in the early days, ‘the Golden Arrow departure platform from Victoria was like a page from Who’s Who.’ A book about the Arrow’s Channel steamer, The Canterbury, lists the following as regulars: Lord Birkenhead, Lloyd George, Jack Buchanan, George Bernard Shaw, Tallulah Bankhead, Gordon Selfridge, the Dolly Sisters, Maurice Chevalier, Lord Carnarvon, Prince Chula of Thailand, Sir Austen Chamberlain, the Aga Khan, the kings of Spain and Romania … and ‘indeed almost every celebrity extant at the time’.

The named trains were used to propagandise railways to children, and the best account of Arrow glamour that I have read comes from The Children’s Railway Book, by Cecil J. Allen, whom I said we would be encountering again. He masquerades here as ‘Uncle Allen’, which sounds alarming to modern ears, but his wife, ‘Auntie’, is present as he escorts his ‘young charges’ – twins called Janet and Peter – about the network. The book is undated, but I think it’s very early ’30s. It contains a chapter called ‘To Paris with the Golden Arrow’, in which ‘Uncle’ and ‘Auntie’ take Janet and Peter to ‘the land of mystery that sometimes they had seen as just a faint, faint line of cliff’ – i.e., France.

Here they are arriving by taxi at Victoria:

‘Golden Arrow, Sir?’ asked the porter, as he flung open the door, and was nearly knocked over by the Twins in their excitement to get out. ‘Yes,’ I replied, laying a restraining hand on my two charges. ‘Some of these bags are to be registered, and the rest we shall take in the carriage with us.’

In those days each platform at Victoria was approached through iron gates, like park gates. The platform number was set into the iron arch above the gate, like a keystone. The platform for the Arrow in its first thirty years was number 2. (From the ’60s it left from number 8).

On the concourse side of these gates there’d be a throng of people who’d come to see passengers off, or just to see the train off. You needed to show your passport to get through the Golden Arrow gate, this literal ‘gateway to the continent’. Immediately on the other side there’d have been the bustle of baggage loading, and passengers would crowd apprehensively around a blackboard indicating the state of the Channel. ‘Sea Slight’ meant you were probably going to be sick on the Canterbury, or that you’d do well to postpone lunch until the Calais–Paris leg.

You would see the perfunctory back end of the train first. In Uncle Allen’s account Janet is intrigued by the very back of the train. ‘Oh, Uncle!’ she exclaims, being only a girl, and therefore ignorant about important matters, ‘What funny little guard’s vans!’ Uncle Allen points out that these are the storage boxes for the registered luggage, at which Janet asks what ‘registered’ means (which I’m glad she did, because I wasn’t sure myself), to be told it means anyone who’s consigned a bag to the van has a ticket to collect it at the other end. Young Peter, meanwhile, is contemplating the carriages, and ‘reverently’ breathing the word ‘Pullman’, quite overawed, even though he’s ‘been running Pullmans on his Hornby railway at home for a year or two’.

He and Uncle walk past the carriages:

Deep and wide glass windows showed us one charming interior after another. There were no ordinary seats; every car was like a drawing room or a lounge, with cosy armchairs scattered about on a carpeted floor, and little tables, each with its electric table-lamp and coloured shade.

They come to the business end of the train.

One glance was sufficient for my nephew. It was clear that his study of my railway books had not been in vain. ‘A Lord Nelson’, he replied promptly. ‘Right,’ I replied. ‘What’s more it’s Number 850, Lord Nelson himself.’

This was the kind of excitement I was hoping to kindle in myself, using the modern railway.

RAIL–SEA–RAIL

I began by attempt to replicate a journey on the Arrow by queuing for an advanced ticket at Victoria. Why Victoria? The Arrow left from there. It might be argued that I should have gone straight to St Pancras International and boarded Eurostar. Surely that is the modern equivalent of the Arrow, being a glamorous train that goes to Paris? There can be no doubt about that glamour. In the late ’90s I wrote an article about Motor Books, a transport bookshop (now closed) in Cecil Court, W1. The owner insisted that he catered to a new, more sophisticated sort of trainspotter: ‘They’re interested in the French high-speed trains, and Eurostar.’ The latter was – and is – our only high-speed train, and its glamour was endorsed in the film The Bourne Ultimatum, in which Jason Bourne travels from Paris to London by Eurostar. (It must have been a toss-up between that and flying, because it is impossible to imagine Bourne, this ‘psychogenic amnesiac’, driving his car on to a roll-on, roll-off ferry.)

Standing in that ticket queue at Victoria, I thought back to my latest trip to Paris on Eurostar. I had been in Business Premier on a press ticket. I recalled rocketing through northern France with the sun setting, and a dinner on the table before me. This dinner had been ‘designed’ by the famous chef Raymond Blanc: cod fillet in sauce armoricaine. The starter had been marinated sardine fillet with cauliflower tartare and fennel.

When I accidentally dropped my napkin, an attendant immediately scooped it up, and to spare me the embarrassment of apologising offered, ‘Anozzer white wine, sir?’ Wagons-Lits (those operators of the Flèche d’Or) are involved in the catering on Eurostar. The pink-shaded table lamps that were a feature of Pullman cars appear in Eurostar Business Premier coaches, and Eurostar, like the Fléche/Arrow is a joint Anglo-French operation. But the Arrow was a boat train, and it was the advent of Eurostar in 1994 that finally killed off the boat trains.

I am glad that Eurostar now commands more of the London–Paris traffic than all of the airlines combined – that it has won London-to-Paris back for the railway – but it is more the murderer of the Arrow than its heir. The Arrow was also a ‘rail-sea-rail’ experience, combining boat and train, which Eurostar does not, and Eurostar runs over a new railway line, High Speed 1, that long post-dates the Arrow.

St Pancras also offers the Class 395 trains (known as Javelins) operated by Southeastern Trains. They go to Dover, but they also use High Speed 1 as far as Ashford International, and they only have one class. This is called ‘Premium’, whereas the few classless Pullman cars were more modestly called ‘Nondescripts’. Premium is apparently ‘Better than standard but not as expensive as first’, which is a case of the operator having their cake and eating it: combining elitism and egalitarianism. But any element of egalitarianism in a train bars it from being compared with the Arrow.

… Which is why I was queuing at Victoria. When I reached the ticket window, I asked, ‘I don’t suppose you can sell me a ticket to France, can you?’ That arch question deserved an arch reply, and the clerk, of Asian origin, asked, ‘Do you doubt it?’ He then proposed a special train and ferry package called a ‘Cheap Day Return to Calais … I will explain all about it, and if you don’t buy, no hard feelings.’ I told him a cheap day return would be no good; I wanted to stay overnight in France. (No one who travelled on the Golden Arrow came back the same day.) ‘Then buy two of them,’ he said. ‘It’s cheaper than buying separate train and ferry tickets.’

‘Is first-class available on that ticket?’ I asked.

‘No. Standard only.’

That was no use either. I then explained that I didn’t just want to go to Calais but all the way to Paris.

‘In that case,’ said the clerk, ‘you’ll need three separate tickets: train, boat, train. First, you go to Dover …’ and he printed out something headed a ‘departure line-up’ (such a nuisance that the word ‘timetable’ has fallen by the wayside). The first morning train shown was accompanied by a note ‘change at Faversham’. Now that was suspiciously far east, and it occurred to me that Dover-bound trains from Victoria, operated by Southeastern Trains, had reverted to the practice of the earlier South Eastern Railway: they all went ‘Up Chatham’. That was not the way the Arrow went. It started from Victoria, but then headed directly south via Orpington, Ashford etc. I explained it was essential that I went over this route, and the clerk – who now clearly thought I was deranged but remained forbearing – explained that trains running by that route to Dover all went from Charing Cross these days. So I had a choice between starting from the right station for the Arrow but going over the wrong route or starting from the wrong station but going over the right route. As I frowned over the Departure Line-Up, the clerk surreptitiously handed me a small slip of paper, about the dimensions of a cigarette paper. ‘Or try these people,’ he said mysteriously. The paper read: ‘Golden Tours – Visitor Centre, 11(a) Charing Cross Road.’ ‘Do they run trains to Paris?’ I asked, incredulously. ‘I think they can help,’ the clerk replied, continuing mysterious.

I thanked him, got on my bike and rode straight towards 11(a) Charing Cross Road. It was a very resonant address, I reflected as I pedalled with mounting excitement along Piccadilly. If any small operator was somehow providing a revived a Golden Arrow-type rail experience, then 11(a) Charing Cross Road would be where they would be doing it from. ’11(a)’, for instance was perfect, echoing the 11 a.m. departure time of the Arrow.

When I arrived at Charing Cross Road, I couldn’t at first find 11(a), but, judging by the adjacent numbers, it seemed to denote a black door bearing a gold plaque, and promisingly located next to a bureau de change at the faded southern end of the street. This, too, was perfect. Behind such a door would be an antiquated clerk of cosmopolitan aspect: a shambolic old gent from the pages of a Joseph Conrad novel. I would gauchely remark, ‘But I thought the Golden Arrow was dead and buried?’ ‘Yes,’ he would reply, ‘that is what most people think …’

But 11(a) turned out not to be the black door. Instead it denoted a glass booth on the pavement, decorated with advertisements for London tourist attractions. A jolly-looking woman sat behind the counter. ‘Can I buy a railway ticket for Paris here?’ I asked, hopelessly.

‘No dear, have you tried Eurostar?’

‘But what is Golden Tours?’

‘It’s one of the firms working from here. It offers BritRail products to foreign visitors. They can’t be purchased by UK residents,’ she added, driving the final nail into the coffin. The decision was made. I would start from Charing Cross, as I had done in the very last days of what might have been called the last boat train …

Charing Cross station today looks bereft, fallen not so much on hard times as small times. If you go to the ticket windows and look up, you will see a stone balcony projecting from the back of the Charing Cross Hotel. London swells used to sit here with their cigars, bought from the station tabac, their drinks and their mistresses (this hotel was traditionally louche), watching the arrival and departure of the boat trains, and contemplating a trip to the Continent themselves, where even better wine, cigars and women were reputed to be available. It has been a long time since anyone sat on that balcony. It’s covered with a net to keep pigeons off, and it hasn’t really been viable since 3.40 p.m. on 5 December 1905, when a defective tie-rod caused the station roof to collapse. Six people died, including an employee of the W. H. Smith’s bookstall on the concourse. The new roof was built cheaper, therefore lower, and if you stood up on the balcony today, you’d hit your head against it.

Until 2007 I often used to queue up at the ticket windows beneath the balcony in order to buy a ticket for the service that was the bathetic heir to the last boat trains: the rail– sea–rail ticket. I might be standing behind a man buying a ticket for Greenwich, and in front of a man proposing to buy a ticket for Orpington. When the man for Greenwich had finished, I would step forward and say, ‘A ticket for Paris, please,’ at which the man for Orpington might give a snort of amusement. But he would quickly cease to be amused when he learned that a ticket for Paris was indeed available; that the clerk would have to go off and find it and that, having found the ticket, he would have to spend five minutes filling it out.

The rail–sea–rail looked like a ticket should: flimsy, and about the size of a chequebook down to its last three cheques. The part giving authority for the ferry crossing was called a ‘Sea Coupon’ and embossed with an anchor. I travelled by rail–sea–rail many times. I used to enjoy looking up Paris in the later years of the National Rail timetable. (It was there, between Parbold and Park St.) The entry tried to direct me to a schedule of Eurostar services, but I ignored that in favour of the note reading. ‘Rail–sea–rail services are offered by Southeastern Trains in partnership with P&O Ferries. Details of these may be obtained by visiting Charing Cross Station.’ A footnote read: ‘NB: Connections between rail–sea–rail services are not guaranteed.’ In the 2005 timetable an even more ominous footnote appeared: ‘The timings for this service are not known’ … not that the timings had ever been given.

A journey on the rail–sea–rail ticket–which was withdrawn in 2007, by which time the railway travel agency, Ffestiniog Rail, was selling a dozen a year, at most – worked like this. You took a train leaving Charing Cross at about seven; you transferred to a mid-morning ferry, then took a train departing Calais at about two and arriving in Paris at about five. It was clear that a journey much like this would be as near as I would get to the Arrow.

I called Ffestiniog Rail. Being a railway specialist, the man I spoke to betrayed no surprise when I said I wanted to duplicate the route of the Golden Arrow. The crucial thing, we agreed, was that I should avoid travelling on a French TGV (or high-speed) train, because although the Arrow had been an ‘express’, that meant at the time an average of 60 m.p.h. rather than the 180 of the TGVs, which in any case take a different route between Calais and Paris from that of the Arrow. I paid just over £100 for ferry and train on the French side. The ticket on the English side I acquired separately.

The Arrow permitted a civilised starting time (11 a.m.) for a cocktail-hour arrival in Paris. But that was in 1929. In 2013 you must set off at 7.10 to reach Paris for early evening.

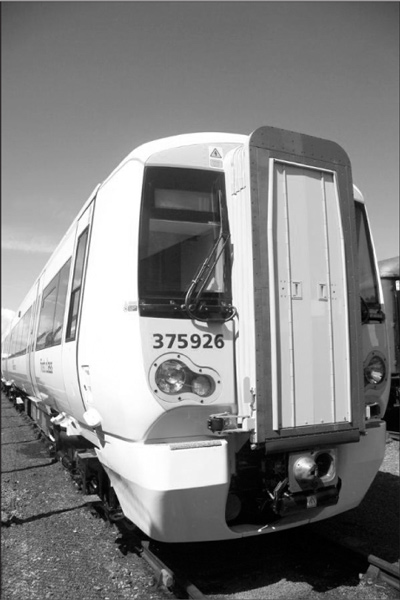

THE ELECTROSTAR

At 6.45 a.m. at bleary Charing Cross there were no crowds of the kind that had waved off the Golden Arrow, but just a few rain-sodden commuters looking up at the departure board. It was late spring, but wintry. A TV screen outside the front of the station had spoken of emergency engineering works on the Dover line, so I was in need of advice. In his book of 1970, The Golden Arrow, Alec Hasenson writes: ‘On the platform the bewildered traveller will find a good-looking BR hostess who will supply him with all up-to-date information about his journey. All the girls speak two or more foreign languages and also carry out duties on the telephone and at the counter of the Continental Enquiry Office at Victoria.’ I walked up to the barrier and consulted a young female platform guard, whose personal appearance is, as we now know, completely immaterial. I asked if everything was all right on the way to Dover. ‘Far as I know it is,’ she said. I mentioned the screen outside. ‘Oh, that dates from last week,’ she said dismissively.

5. An Electrostar 375, heir – in a way – to The Golden Arrow.

I could think about food. Those boarding the Arrow would already have eaten breakfast, probably in the Grosvenor Hotel adjacent to Victoria station, but they were offered a mid-morning snack on departure: coffee or tea and smoked salmon or chicken sandwiches. ‘And’, says a brochure for the Arrow dating from the 1940s, ‘if you happen to ask for cigarettes, don’t think you’re dreaming when he [the attendant] answers with a smile, “Yes sir, how many would you like?” and stands by with a match.’ The cigarettes served on the inter-war Pullmans were called Abdullas. The label read ‘Turkish Egyptian Virginia’, whatever that meant.

I walked into W. H. Smith’s at Charing Cross and surveyed the elegantly named Foo Go sandwich range. No chicken or smoked salmon, but egg sandwich always feels like a railway sandwich to me, so I bought one of those. Egg and cress, it should really have been. (The railways put egg and cress on the map.) I bought a coffee in a cardboard cup from the chain called Délice de France – the name, for once, sort of appropriate. I went through the barrier and approached the train. Whereas I would have been greeted by an attendant at the carriage door if travelling on the Arrow, before being shown to my seat by another attendant, boarding the 7.10 for Dover was a lonely business. The train, operated by Southeastern, was an electric multiple unit – an Electrostar 375, if you must know. A multiple unit is a train with its motive power – its engines – distributed at intervals along the length of the train. There is no locomotive. The driver drives from a cordoned-off part of the front carriage. There are diesel and electrical multiple units. Most multiple units are about as exciting as the term suggests (but see the next chapter for an exception).

I walked to the very front, and boarded first-class: ten empty seats, insufficiently divided from standard seats in the rest of the carriage for my liking. Not that there was anyone else in the carriage. The seats were plum-coloured, with yellow dots. The only real difference between these and seats in standard was a blue antimacassar. If I’d gone into standard and a put a clean blue handkerchief between my head and the seat, I would effectively have been travelling in first. (On Pullmans the antimacassars were known as ‘antis’, and those on the Arrow were of embroidered linen.)

There was much shuffling about of cars during the first years of the Arrow, but for simplicity’s sake let’s say they were all of the Edwardian sumptuousness described in the introduction. The very first cars were inherited from the White Pullman. One of them was called Fingall, and it has been preserved on the Bluebell Railway. Fingall had (and has) a floral theme on the marquetry, dark blue carpets, armchairs of a mid-blue decorated with silver leaves. Fingall is a kitchen car: twenty-two places for diners, plus a kitchen. The seating is 1+1. Single men boarding a first-class Pullman might collude with the attendants to be seated opposite an attractive woman. But, since this was an open carriage, any too forward behaviour would be observed, whereas compartments were, in the words of the Oxford Companion to Railway History, ‘convenient for sexual assaults’, as we will be seeing.

The Electrostar juddered into life, and an automated announcement informed me – for the first of what would turn out to be about thirty times – that the train would be dividing at Ashford International, the rear four coaches going on to Canterbury West, the front four to Dover.

I hate train announcements, but in fact the post-war Golden Arrow was fitted with a pioneering loudspeaker that allowed the conductor to talk to passengers ‘who,’ as Alec Hasenson writes, ‘had become accustomed to being talked at by such means in stations, camps, ships and airports in the war … Such a thing would have been unthinkable before the war, even on such “matey” excursions as the Eastern Belle.’ The modern injunction ‘Please remember to take all your personal belongings’ was prefigured in that, on arrival at Dover, the conductor reminded passengers not to forget their umbrellas.

We rolled away towards the first of the fourteen stops we’d be making before Dover: London Bridge. I had a view of the misty river and Parliament. Those leaving Victoria on the Arrow in its first years would have seen the river and Battersea Power Station under construction.

In about 2002, when I was on one of my rail–sea–rail jaunts, a Maltese gent boarded at London Bridge and set a rail–sea–rail ticket on the table in front of him. Unable to believe he was a fellow nostalgist, I asked if he’d ever heard of Eurostar. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but I am afraid of it. I would rather be on the sea than under it.’ I thought I would give him a vicarious thrill by telling him about something that had happened to me on Eurostar in 1996 …

We were proceeding towards the Chunnel in a heavy snowstorm. We entered the tunnel so tentatively that I thought, ‘The driver doesn’t fancy this very much. Something bad’s going to happen.’ At the mid-point, sure enough, the train stopped abruptly. Alongside me were some men playing bridge. After half an hour the guard made an announcement: ‘The driver informs me … that this train cannot go.’ ‘Oh dear,’ said one of bridge players. Over the next couple of hours the train began to expire. The air-conditioning and the heating stopped working. The lights would periodically flicker. I knew something really serious was amiss when the guard announced that food and drink were being given away in the buffet. I went and got a sandwich and a half-bottle of wine, feeling like the condemned man eating his last meal. In the buffet I met a German engineer, who said he was ‘very interested’ to see whether the train, having been stuck for so long in the same position, would crash through the bottom of the tunnel. ‘I cannot see why it would not happen,’ he said, smiling. An hour later, I was back at my seat when all the lights went out. The guard came into the carriage and placed a torch on one of the tables. When the torch failed, one of the bridge players said, ‘This really is rather irritating.’ After six hours we were pushed to Calais by another loco. A few weeks later, I was sent a full refund and vouchers entitling me to two complimentary returns. When I presented these at Waterloo (which was the Eurostar terminus in those days), the ticket clerk said, ‘Wow, you must have had a really terrible delay.’

The Maltese gent had remained silent at the end of the story, and indeed all the way to Dover.

After half an hour we were at Chislehurst, in the middle of bright green woods, where, in circumstances of great complexity and apparent secrecy, the railways meet: the old South Eastern main line and that of the old London, Chatham & Dover. I was now properly on the route of the Golden Arrow and soon flashing through Petts Wood and Orpington, where I looked at commuters waiting for London-bound trains with as much arrogance laced with pity as if I’d been on the real Arrow. All the while the line was climbing. On a modern train you don’t notice, but in The Children’s Railway Book Uncle Allen mentions that, on reaching the end of the climb at Knockholt (17 miles from Victoria), ‘the loud voice of Lord Nelson quietened, so that we could no longer hear it.’

Then it was through the mile-and-a-half Polhill Tunnel, emerging on to the North Downs under light rain. In his book Pullman in Europe George Behrend wrote: ‘The wide view to the left hereabouts is one of the most beautiful in Britain and always seems to the author typically English as though challenging the departing traveller for leaving the country.’ Yet Behrend, an expert on international luxury trains (as well as a distinguished soldier, an expert on the art of Stanley Spencer and sometime chauffeur to Benjamin Britten), often did leave the country. I spoke to him once in the mid-1990s. He was getting on by then, and he said he didn’t much care to be in a world that lacked the Golden Arrow and its nocturnal counterpart, the Night Ferry.

We were approaching Sevenoaks, the right geographical point to consider the Night Ferry, for a reason to be revealed after a bit of history.

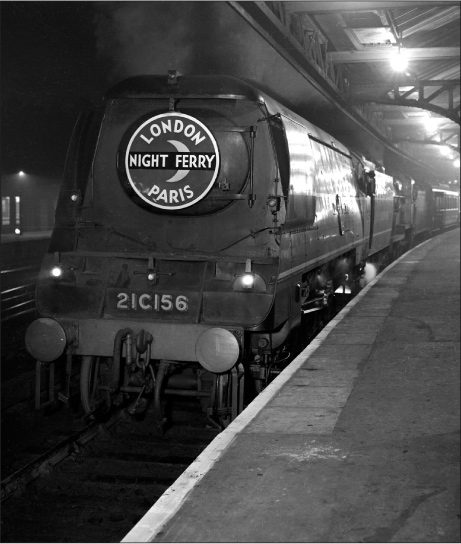

When I mention the Golden Arrow, people tend to say, ‘Wasn’t that the train that was put on to the boat?’ No. That was the Night Ferry. It began operating in 1936, leaving Victoria Platform 1 at about 10 p.m. (the timings varied over the years), arriving in Paris at about 9 a.m., and vice versa. At Dover or Dunkirk the carriages were shunted on to a special ‘train ferry’, supposedly ‘while the passengers slept’. In practice, what with the shunting, the tremendous susurration, general shouting, swearing and noises-off as the sea level was adjusted in the train ferry dock, followed by the clangourous shackling down of the carriage bogies in the echoing hold of the boat, passengers did not sleep. They put on their dressing gowns and padded up to the ferry’s bar. It was the amphibious nature of the train that made it so famous. There was a lifebuoy in every compartment, and every compartment was a sleeper. There was also a Pullman restaurant car. It was a French train, built and operated by Wagons Lits, with carriages of a seductive dark blue, trimmed down slightly to the British loading gauge. (‘Loading gauge’ refers to the dimensions of the carriages, as opposed to the track gauge – the distance between the wheels – which is uniform throughout Europe. French carriages have bigger dimensions than British ones, which is partly why they seem more comfortable.)

6. The Night Ferry, leaving Victoria in December 1947. Its carriages were loaded onto a cross-channel boat, supposedly while passengers slept.

The locos that drew the train bore a nameboard featuring a crescent moon. The Night Ferry wasn’t the first train to be put on a boat. Train ferries were used to cross the Firths of Forth and Tay until the waters were bridged in 1890. There are many train ferries still operating. In his book Italian Ways (2013) Tim Parks describes the train ferry between Calabria and Sicily. He leaves his compartment on the train to go up on deck and take pictures of the setting sun, but then he can’t find his way back: ‘You would have thought it was easy to find a train in the bottom of a boat, but actually, no. There were an extraordinary number of stairways and corridors, and no signs telling passengers where to go.’

The Night Ferry ran for the last time on 31 October 1980, by which time electro-mechanical indicators had been installed at Victoria. On that night the indicator on Platform 1 read, ‘Au revoir mon ami,’ and the driver brandished a copy of the London paper, the Evening News, which also shut down that night.

I never went on the Night Ferry, but a year ago I met a man of about my own age, Dr David Haslam, whose father was a railwayman, and who also went on jaunts with the British Rail Touring Club, including one involving the Night Ferry. I asked him what he’d thought of it. ‘In a word, cosy,’ he said. ‘When I got back to school after the holidays, I was asked what the French word for train was, and I got told off for saying “Wagons-Lits”.’

As our Electrostar approached Sevenoaks, I recalled the one time the Night Ferry stopped to pick up a passenger before Paris. It was on 16 December 1951, when the Night Ferry called at Sevenoaks to collect Winston Churchill. His country seat, Chartwell Manor, was at nearby Westerham, along a branch line now closed. The Night Ferry conductor had been given orders to put a bottle of Dewar’s White Label whisky, soda water and cracked ice in Churchill’s compartment.

Churchill was a regular on both the Night Ferry and the Arrow. The attendants were advised not to ask him if he wanted an aperitif. ‘I don’t need an aperitif to have an appetite,’ he would growl. Another reason he didn’t need one was that he was already drinking something else. Another notable regular on the Night Ferry was the violinist Yehudi Menuhin. And in 1978 Ernest Marples, the former transport minister, builder of roads and recruiter of Dr Beeching, fled Britain for Monaco using the Night Ferry. He was avoiding a big tax bill. Many of his possessions were left at his Belgravia flat; others were loaded into tea chests and put into the baggage wagon of the Night Ferry. It was a good job for Marples that his man Beeching hadn’t cut the service, as he had so many others. Marples never returned to Britain.

When our Electrostar stopped at Sevenoaks, at 7.42 a.m., a crowd of schoolchildren climbed up. They were perfectly well behaved, if noisy, but I resented these boarders. The fact that both hand luggage and passport examinations happened on the Arrow guaranteed that it would not stop to pick up or set down passengers. To do so would have created what is now called a security risk.

We buzzed (the Arrow would have roared) through the two-mile Sevenoaks Tunnel and descended towards Tonbridge, where the noisy schoolchildren got off, and some even noisier schoolchildren got on. Then came Paddock Wood, in the Weald of Kent. The Weald, as seen from windows of the Golden Arrow in the 1930s, would have been all fruit orchards, hop gardens and oast houses. The majority of the Kentish orchards and hop gardens have been lost, but some oast houses remain, like funny hats. The passing fields were small and – now that the rain had cleared – bright green, often with a haze of bluebells, and scruffy horses standing in them.

When we reached Marden, the day had become properly sunny. It checked my watch (whereas on the Arrow I would simply have looked at the clock at the end of the carriage). It was 8.04. The Arrow would have sped through Marden shortly after mid-day, and passengers would be thinking about walking through to the bar car. The Arrow had a number of bars cars down the years, and the actual bars within them were always called Trianon. The name, chosen by John Elliot, was taken from two small castles found in the grounds of the Palace of Versailles. The most famous Trianon was the one that appeared when the Arrow was re-launched after the wartime suspension.

In 1946 a booklet called London to Paris, a Journey in Pictures, was produced to mark the re-launching of the Arrow. It was written by someone called George C. Jury. ‘It’s “chic”,’ he writes of the new bar, ‘done in pale pink and grey plastic throughout. The little lounge compartment is very cosy – plastic too, even to the curtains.’

Jury, I suspect, was chosen for his ultra-modern prose style, which is incomprehensible. Here he is (I think) defending the Arrow against criticism that a luxury train ought not to be revived at a time of austerity:

The voice of Austerity whispers, For Shame! That Trianon’s modicum of comfort should be a substantial reason for riding Parisward this way! A far, far better thing it ought to be that the Arrow does you Paris, or from Paris does you London, with a save of anything from four to thirteen hours, which, multiplied like the efficiency experts can’t help doing it, would aggregate to something disturbingly unprogressive.

The plastic bar lasted until 1951, when it was replaced by another Trianon, fitted into a car called Pegasus. In 1963 this became the Nightcap Bar on the Night Limited (my favourite name for a train full stop), a sleeper service from Euston to Glasgow. In the ’90s this carriage was restored and brought up to spec to run on main lines of the modern railway. It formed part of a diesel-hauled train comprising some replica Pullman cars (along with Pegasus) and providing a ‘railway cruise’. In the year 2000 I went on this cruise. Over the course of five days we roved over the north of England and Scotland, and I sat next to a charming American called Tom Savio. Over Brut Premier Cuvée champagne, Scottish smoked salmon, caviar and scrambled eggs – in other words, breakfast on the second day – Savio explained all about our Trianon bar, which resembled a cocktail bar in a good hotel, with a marble top, a chrome rail along the front, and, behind the actual bar, an image in Lalique glass of Cupid firing an arrow from London to Paris. Savio gave me a copy of his book, The World’s Great Railway Journeys, signing it ‘Railway Dreams’. Savio is known as ‘the railway baron’. Aside from writing railway books, he had been the assistant curator of California State Railway Museum, Sacramento, California, and, even better, stationmaster at the small town of Davis, California. He revered Britain as ‘the motherland of railways’. ‘With respect,’ he told me, as we were rolling past a sunlit Loch Lomond, ‘your country is like a model railway layout.’

… Then again, if I – as an Arrow passenger – couldn’t be bothered to leave my seat as we ran through Marden, I might press the bell to summon the attendant. Since Paris was in the offing, I might order a quarter-bottle of champagne. Quarter-bottles were first seen in Britain on Pullman coaches. They were introduced in 1947, because passengers always seemed to want some champagne – but not too much – to fortify themselves for the Channel crossing. Quarter-bottles of red and white burgundy, red and white Bordeaux, a hock and a port were also available.

At 8.08 a.m. we stopped at Staplehurst.

At 3.13 p.m. on 9 June 1865 ten people were killed and fourteen were injured in a train crash on a viaduct near Staplehurst. One of the survivors was Charles Dickens.

The train was an express from Folkestone to London. Workmen had taken up the track in order to repair a fault in the viaduct, and they seemed to have forgotten about the ‘up’ train from Folkestone. The confusion arose because it was a ‘tidal’ train, as were most boat trains up the 1880s, before harbours were deepened to allow boats to dock at regular times irrespective of tides. Early Continental timetables showed perhaps half a dozen departure times – varying between, say, seven in the morning and two in the afternoon – for any given boat-train service, depending on the tide.

Nonetheless Dickens was a regular on the boat trains, which connected him with his mistress Ellen Ternan, whom he’d set up in a house near Boulogne. He had been ‘enchanted’ by getting from London to Paris in eleven hours in 1851. He blessed the South Eastern Railway Company ‘for realising the Arabian Nights in these prose days’. However, he had disliked trains other than boat trains before the Staplehurst crash, and he disliked the generality of trains afterwards, always clutching the arm-rests of the seat, and feeling the carriage was ‘down’ on the right-hand side.

The 1860s was the worst decade for railway accidents, when train numbers and speeds were outstripping safety provision. The worst of the decade occurred at Abergele, in Wales, where runaway paraffin wagons – vehicles obviously emanating from some signalman’s nightmare – collided with the Irish mail train from Euston. Thirty-three people were instantly immolated. A year after Staplehurst, Dickens wrote the best of his ghost stories, The Signalman, which is about a train crash in a tunnel. We will be considering this in the next chapter, since it was ‘inspired’ not only by Staplehurst but also by a smash that occurred on the Brighton line.

Twelve minutes after Staplehurst, we came to Pluckley. Speaking of ghosts, Pluckley has the reputation as the most haunted village in Britain. Difficult though it was to believe on this bright morning – or on any morning – it is on the route of a phantom coach and horses: there’s an old mill haunted by an old miller, and a ghostly monk, a Red Lady, a White Lady, a poltergeist in the Black Horse inn, over the road from which the ghost of a schoolmaster who hanged himself has been seen dangling from a tree.

I would have thought that to read a ghost story, or any book, on the Golden Arrow would have been to miss the point. You should be looking out of the window, eyeing up your ‘+1’ or savouring the food and drink. But in 1948 BR, W. H. Smith’s and Pullman combined to institute a bookstall service on the Arrow. I own copy of a magazine called The Railway Digest from that year, and it shows a ‘bookstall boy’, dressed as a Victorian urchin, proffering a rack of books to languid-looking, cigarette-smoking passengers. Why the urchin get-up? I frowned over this for quite a while before reading the small print, which revealed that the whole stunt was by way of celebrating the centenary of W. H. Smith’s.

At 8.30 we reached Ashford International, and here were more ghosts, in the form of the old loco and carriage works, which closed in 1962. They are now largely a retail park. Ashford is called ‘International’ because Eurostar calls there, but the station has been upstaged by – and lost Eurostar services to – Ebbsfleet International. Railway traditionalists consider the suffix ‘International’ pompous. It was never ‘Victoria International’, even when it was the ‘gateway to the continent’.

At Ashford the train divided; our front half rolled on towards Dover. There was only one other passenger in the carriage with me: a youth who fell asleep on departure, with mouth wide open. We came to Folkestone, rumbling over the nineteen arches of the Foord Viaduct, which commands a view of the town in its entirety. (The youth was now snoring.) The Channel lay to the right, glittering and beautiful but completely empty, whereas in 1970 Alec Hasenson had written, ‘The steamers are just discernible amongst the harbour cranes.’ Most of the intercontinental action at Folkestone is now under the sea, because it is here, beneath Shakespeare Cliff, that the Channel Tunnel begins.

We came off the viaduct and began threading through the cliffs, the sea appearing intermittently on the right. This run is called ‘the Warren’, and it is the ultimate English theme ride, in that you are actually penetrating the White Cliffs of Dover. The track here has suffered many landslides, with particularly severe ones during both the First and Second World Wars, as though symptomatic of a momentary collapse of confidence. Emerging from the cliffs, we curved left, heading inland and past the remains of Dover Harbour station, which closed in 1927 but remains shockingly dead, like a corpse in the street. We were heading towards Dover Priory, the only surviving railway station in Dover. At least half a dozen others have come and gone, the result of the competition between the South Eastern and the London, Chatham & Dover.

The building that housed one of those half-dozen survives on the edge of the sea. Craning to the right, I looked at it with a certain longing, because this was once Dover Marine, where Golden Arrow passengers disembarked to begin their Channel crossing.

DOVER MARINE: A DETOUR

Dover Marine station was built as part of the widening of Admiralty Pier that was completed immediately before the First World War. In the Deco style, it looks somehow Egyptian, or like a giant mausoleum, its great maw facing inland to suck up incoming trains that never arrive, since all the railway approaches have been lifted and turned into a lorry park.

I formulated my plan to visit Dover Marine a few weeks before undertaking my Golden Arrow journey. I was at Deal with my wife. She loves looking around the antique shops there, whereas I quite like looking around them. ‘I have an important closed-down railway station to go and see,’ I told her, as she sifted through some Victorian napkin rings, and – making an arrangement to see her back in Deal for dinner – I was off, racing along the A258 to Dover docks.

In Dover the situation was much as it has been for the past twenty years: the white Georgian houses of the Marine Parade looking ghostly in the centre of the otherwise unlovely sea-front; the giant car ferries coming and going metronomically from the Eastern Docks, which has been the base of all ferry activity since 1994, and a dreaming silence on the western side, where Admiralty Pier and the building formerly known as Dover Marine stand.

A towering, apparently empty, multicoloured cruise ship was tethered to Admiralty Pier, like a Eurotrash blonde on the arm of a decrepit English gentleman. Dover Marine closed as a station – and a transfer point to ferries – in 1994, when Eurostar commenced.

Today the Dover Marine building, in conjunction with the landward end of the pier, is a cruise ship terminal, and if you are the passenger on a cruise ship docked at Dover, you have a pass enabling you to come and go. But if you are a writer who’s turned up on the off-chance, you can forget it. The ferry terminal is guarded by G4S staff clad in fluorescent orange. They control a barrier located two hundred yards in advance of the building. From there I could make out where the platforms had been, and I could see the iron gantries of the roof, under which, in the mid-’70s, I had watched my father carry our family’s two suitcases, repeatedly stopping to set them down in order to let the blood flow back into his hands, or to check that, yes, all the passports and tickets were in his inside pocket … because even passengers arriving on ordinary trains for ordinary ferries used to go from Dover Marine.

‘Do you get many rail enthusiasts turning up?’ I asked the G4S man.

‘The odd one,’ he said, with the emphasis on ‘odd’.

‘Is is still recognisably a railway station?’

‘Oh yes,’ he said, ‘it’s pretty much as was. Look, I’m sorry I can’t help you, but try giving this number a call.’

The number was for the Dover Port Police, and the idea was that I would get authorisation to enter the building. I called it a couple of times, listening to a series of messages referring me to other numbers that also went unanswered. I was forced to conclude that the police at Dover port took Saturday off. But the Dover Transport Museum – a scruffy, enthralling barn of a place on the edge of town – is open on Saturdays.

A rusting hovercraft propeller is propped outside the entrance. It commemorates what was in retrospect the short-lived and eccentric heyday of the hovercrafts (if that’s the plural) which operated alongside the cross-Channel ferries between 1968 and 2000. They took only thirty minutes to cross the Channel, but carried only carried about thirty cars and two hundred and fifty passengers. Not enough of either; and the end of duty-free shopping in 1999 killed them off.

A man selling tea and cakes in the Dover Museum told me his uncle had worked as a signalman at Archcliffe Junction, Dover, and sometimes he’d telephone to say, ‘The Arrow’s coming down if you want to have a look.’ I talked to another man, a visitor to the museum, who said he’d spent many evenings inside the Marine station as a boy. ‘I wasn’t intending to go anywhere. It was just a place to hang about in the evening. It was brightly lit, warm – well, warmer than outside – and there was a bookstall and a café. The café was always full of fishermen, coming in out of the rain for a bottle of beer.’ He liked the sound of the sea echoing about in the station, and the screaming of the gulls.

In the late afternoon I returned to the waterside. There was a beautiful golden haze in the air, and a new man on the G4S barrier. He blocked me, just as his colleague had, but he indicated a rusting gateway a few feet off. It gave access to a stone staircase, and a structure I had somehow overlooked among the salt-stained hangars of Dover docks: an elevated, enclosed walkway circumventing Dover Marine but running closely alongside the western side of its roof and leading to a staircase giving access to Admiralty Pier. The walkway, with its peeling blue and pink paint (a raddled remnant of Edwardian seaside gaiety) and frequent puddles of seawater, was a genuinely frightening place to walk alone, but I was consoled by the sight of an elderly red setter standing beside a ticket booth at the seaward end. From the booth the dog’s master checked the permits of fishermen going on to the pier. Immediately left of this booth was a lateral extension of the walkway that had once given access to the upper regions of Dover Marine, but this was all blocked off.

I descended onto Admiralty Pier and tried, as it were, to crane around the bulk of the old Marine station to see the bit of quayside adjacent to it. Here the Arrow’s own steamer, the SS Canterbury, had waited, in the very spot occupied by the garish cruise ship. A small crane winched the luggage aboard. This was done in one go, the Arrow’s luggage van comprising a single container atop a flatbed truck. As the passengers walked up the gangplank, the Arrow’s locomotive would have been turned on the turntable where the lorry car park now stands, and the attendants would have switched the menus around, so passengers boarding the train from the ferry (having left Paris on the Flèche d’Or) would be offered afternoon tea rather than mid-morning sandwiches or an early lunch.

On the way back to my car I stood outside what had once been the Lord Warden Hotel, a beacon of early Victorian elegance on the Dover dockside. For many years cross-Channel travellers stayed here, including Thackeray and Charles Dickens, who resented being turfed out of bed too early in the morning, before boarding the steamer on a wild and dark sea. Shivering and bilious on the Channel, Dickens would look back at the illuminated hotel. ‘I know the Warden is a stationary office that never rolls or pitches, and I object to its big outline seeming to insist upon that circumstance.’ In the Second World War the hotel was known as HMS Wasp, HQ of the Naval Coastal Force. It later became an office of BR Southern Region. Now, although it has a closed-down air, it is something to do with Dover Port Authority. George Behrend wrote of the hotel that ‘It might have been built for the railway student, with the turntable slap outside the lounge windows.’

I was now late for dinner in Deal … but a shuttered pub close to the Lord Warden caught my eye. It was called The Golden Arrow, the name seeming burned into the panel above the boarded-up windows. I had read about this on the internet – from the archive of the Dover Mercury. The pub had previously been called The Terminus. It was renamed The Golden Arrow in 1962, by which time the train was hauled by an electric loco, on which it was impossible to fit the down-pointing arrow and the big, intertwined British and French flags that the Arrow had carried since the war. Instead, the engine carried in its front a sort of plank reading ‘Golden Arrow’, and two small flags, about the size of the things children stick on sandcastles. But the train’s loss was the pub’s gain in 1962, when the landlord, Mr P. Pettet, ‘was presented with the headboard from the famous steam train of that name by railway representatives’. He was also given the old flags. The article continued: ‘BR said they could think of no more suitable resting place for the Golden Arrow regalia, as the public house stands opposite the Marine Station and is greatly used by railwaymen.’

The pub was closed in 1987. It then became a profound contradiction in terms: The Golden Arrow Truckers’ Diner. This development was also chronicled by the Mercury: ‘Maintaining its link with the past, the diner features a specially designed board outside, recalling the days when the famous steam train, the Golden Arrow, called at Dover.’ That has long gone. One part of the window was un-boarded up, and I squinted inside, half-hoping to see some Golden Arrow regalia gathering dust, but there was just a wall painted dark below and white above, with a wave effect at the top of the blue, like a primitive representation of the sea.

TO ‘THE CONTINENT’

Arrow passengers arrived at Dover Marine at 12.35 and were departing on the steamer at 12.55, and if that’s not integrated transport I don’t know what is. By contrast, the 7.10 from Charing Cross carried me into Dover Priory at 9.02, and my ferry was not due to depart until 11.15.

After disembarking at this bland bunker of a station, I walked around the corner to where the buses leave for the Eastern Docks. There I took my place under the dispiriting sign familiar from rail–sea–rail excursions: ‘Passengers are reminded that ferry operations are not train connected and we cannot guarantee the bus service will connect with either ferry or train services.’ This used to be a courtesy bus, but the fare to the docks is now a pound. The implied message is clear: ‘By using the ferries in the old-fashioned way – as a foot passenger – you are being a thorough nuisance, and we would rather you either drove onto a ferry or used Eurostar.’ It was the French who started it, introducing a charge in 2004 for the equivalent bus on their side: the one from Calais Harbour to Calais Ville station. And the French ferries have refused to take foot passengers for years.

The bus took eight of us to the sleepy foot passenger reception for P&O Ferries. But, while sleepy, it is also friendly, and the woman at the ticket desk said I could board an earlier ferry, the 10.15. ‘But what about the hour-long check-in time?’ I said. She just shrugged and smiled. From there we boarded another bus that took us across a car park to a metal detector in a gloomy hangar. Our reward for passing through the detector was a small red card reading ‘Bon Voyage’. This entitled us to board another bus, which carried us towards the ferry gangway. The gangway is almost entirely enclosed, but at the very top, as you pass into the ferry, you are briefly in the open air and looking down on all of Dover, with the wind in your hair and seagulls crying.

Then you are into the ferry – in this case the Pride of Burgundy (launched in 1992) – and all maritime sensations recede once again. Ferries are now floating shopping arcades-cum-multi-storey car parks, with stabilisers that banish almost any possibility of seasickness. When, during the safety announcements, reference is made to ‘the vessel’, you are surprised at the word. As a boy, I crossed the Channel on the ferries of Sealink, the seagoing arm of BR. Some were for foot passengers only; some had car-carrying capacity. Either way, you could have fitted three of them into the Pride of Burgundy, and you knew you were on a vessel. At any one time about a quarter of the passengers were throwing up. Some of the Sealinks were operated by the French, and I preferred these because the coffees were fascinatingly smaller and the sandwiches fascinatingly bigger: long and thin baguettes, and with simple ingredients – pâté or cheese – yet still delicious. (I speak as someone who’s never been seasick.)

For those Arrow passengers with sea legs, the crossing was the time for lunch. For those without, it might be time for another dose of the pills – Aspros, they were called – offered for sale on the train. The Pride of Burgundy Food Court offered a ‘meal deal: curry and beer, £7.99’. There was also the Commercial Drivers’ Restaurant, for which I lacked accreditation, and the Costa Coffee outlet in the ‘family lounge’. Un-tempted by these, I loitered in a gangway and went into a daydream about the Golden Arrow’s private steamer.

The SS Canterbury must be one of the very few cross-Channel steamers about which a biography has been written, and I use the word advisedly, such is the loving anthropomorphisation of the vessel in the 150 limited-edition pages of The Canterbury Remembered by Henry Maxwell, who self-published the book in 1970. ‘The Canterbury’, he begins, ‘was a queen. She stood apart from the ordinary. There was regality in her every line. She was the best known, certainly the best-loved cross-channel steamer there has ever been.’ He then gives her technical specifications, her vital statistics as it were. Her elegance he attributes to ‘a slightly different rake here, a modified prop there, a mere gradation in scale elsewhere’, and let me assure the lay reader that in any picture book of cross-Channel ferries the Canterbury does look the slimmest and sleekest.

One of many curious things about Henry Maxwell is that he was not an expert on shipping. He worked in the offices of ICI, and his introduction to the Canterbury was through the Evening Standard: ‘I was turning the pages idly and suddenly there it was, and I became immediately excited: a new cross-Channel steamer for the Dover–Calais service.’ It is difficult to know whether this points to the peculiar obsession of Mr Maxwell, or the fame of the Golden Arrow. Maxwell goes on to say that ‘The Golden Arrow steamer was “news”. She need only to be delayed to find herself upon the front page of the evening newspapers … What was new and distinctive about her’, he gushes, ‘was the unwonted spaciousness and luxury of her passenger accommodation and furnishings.’

The Canterbury could accommodate 1,700 passengers, but the 300 stepping aboard from the Arrow had her all to themselves. Whereas the foot passenger of today feels like a second-class citizen, decanted by an obscure train onto a boat catering primarily to motorists (‘Foot passengers please await further announcements’), Arrow passengers were accompanied onto the Canterbury by the conductor of the train, who was on hand to give advice about the onward journey, for which duty he exchanged the cap he’d been wearing on the Arrow for a jauntier, more seagoing one.

And whereas the modern ferry is an indoor affair, apart from a ‘deck space’ (in effect, a smoking space) about the size of a prison exercise yard, the Canterbury supplied a distinctively maritime experience. As Maxwell writes:

In good weather the Boat Deck offered a real promenade and the awning deck became virtually a single, huge saloon. All along its sides and down the centre were comfortable bays or recesses composed of high-backed armchairs arranged face to face with a table in-between in groups of four, almost like the coupéd [sections] of a Pullman car.

At the end of this extended lounge was ‘nothing less than a palm court’. A palm court was the ultimate 1930s’ amenity, but they were usually found in grand hotels or ocean liners, not cross-Channel ferries.

The dining-room, reports Mr Maxwell, was on the main deck. It resembled a Parisian brasserie or, as Maxwell writes, was ‘predominantly Empire in character’, featuring light cream walls and mahogany pillars with ‘a delicate golden arrow running vertically up their flutings’. Aside from the public rooms there were eighteen private cabins for use if, for example, you were the king of Spain.

But it couldn’t last. The whole operation was anachronistic from the start, what with all those cars and electrical trains swarming around, and the aeroplanes massing overhead. Maxwell knew this. His book is as much a condemnation of the world that killed the Arrow/Canterbury as a celebration of the de luxe combination. We might as well get it out of the way here: the painful story of the Golden Arrow falling to earth.

First came the economic depression and devaluation of sterling, which discouraged foreign travel, Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald refusing the ‘modest reduction in unemployment relief’ that might have eased the crisis, according to our Mr Maxwell (who was evidently no socialist). In 1932 a couple of the Pullman carriages on the train were replaced by ordinary Southern Railway second-class ones. On the Canterbury the Palm Court became the second-class deck saloon. By 1939 the number of Pullmans on the train had dwindled to four.

The Arrow was suspended during the war, and the Canterbury served in the Dunkirk evacuation, in which patriotic cause she finally reached – indeed exceeded – her passenger-carrying capacity.

The Golden Arrow was reinstated with much fanfare – and intertwined Union Jack and Tricolour flags on the buffer beam – in 1946. There were now ten first Pullmans, each in the traditional umber and cream livery. The Labour government of Clement Attlee was happy to flaunt the luxury of the restored Arrow as being a return to business as usual, and the Arrow was once again teamed up with the Canterbury.

But the Palm Court was not restored, and, as Maxwell notes, a ‘rather regrettable’ notice appeared advertising ‘Restaurant Bar and Tea Lounge’. From October 1946 Arrow passengers were usually carried on another vessel, Invicta. Folkestone became the home port of the Canterbury, the vessel ceding her pre-eminent position ‘with her customary grace’, although Maxwell records her captain as resenting having to use the Canterbury to carry these ‘hordes of trippers’ to Boulogne. Then came BR and the ‘grotesque colour scheme which our nationalised railways have seen fit to adopt for what they all too aptly designate as “ferries”’.

In 1951 Pullman built a rake of new cars (including firsts and seconds) for conveying dignitaries to Paris during the Festival of Britain celebrations. Among the names were Aquila, Carena, Cygnus, Hercules, Orion, Pegasus and Perseus. These cars, which are considered the last ‘traditional’ (if not quite ‘vintage’) Pullmans, then began to operate on the Golden Arrow. The rationality of the ’50s did not mix with Pullman sumptuousness. The cars were more pallid and spartan than their predecessors, and the occluded lavatory windows were rectangular rather than oval, making the whole car appear less Palace of Versailles-like. (Pullman lavatory windows had been oval since 1906.) The cars still had the armchairs, the silver service, the wood panelling (albeit without marquetry), the pressed white tablecloths and the table lamps, now ‘with French old gold finish’. (According to George Behrend: ‘A Pullman car in service without its table lamps is like a Mayor attending an official function without his chain of office.’)

In 1953 the first roll-on, roll-off car ferries were operated from the Dover Eastern Docks. The final steam working of the Arrow was on 11 June 1961. The engine was named Apple-dore. The next day the train was drawn by an electric locomotive: E5001.

On 15 September 1961 the Canterbury was put to the indignity of a ‘bingo cruise’ from Folkestone to Boulogne and back. By now, Maxwell conceded: ‘The aeroplane and the motor car between them have taken the cream of the passenger trade away forever.’ In 1963 BR integrated the Pullman Car Company, which it now owned, with British Transport Hotels Ltd, and this company took over management of the Arrow. The last Trianon bar car was removed from the train. ‘Attendants’ became ‘stewards’; what had formerly been ‘chairs’ were now ‘seats’.

On 29 July 1965 the Canterbury, this ‘product of the era of studied elegance and inviolable proportion … the Augustan age of marine architecture’, was towed from Dover to Belgium for scrapping. Let Maxwell have the last word: ‘She was spared the journalistic sentimentality and vulgar obsequies of a “Last Voyage” … Last salutes were blown to her from the sirens of her consorts on the Channel service and from the tugs and tenders of the Dover Harbour Board as the final cortege passed out of the harbour.’

By then, the Arrow was down to four first-class Pullmans, supplemented by ordinary second-class BR coaches, with a second-class buffet to serve this rabble. In 1967 the cars were painted in the new BR livery of blue and grey, and a generic ‘Golden Arrow’ was painted over their original names. In 1969 the last Pullman/Wagon-Lits car running on the French side was removed, and the name Flèche d’Or was dropped.

According to a memoir written by Alec Hasenson for the website Coupe News, there was a ‘mad scramble’ for seats on the last ‘down’ Arrow, which, on 30 September 1972, was seen off from Platform 8 at Victoria with ‘cheers and bangs’. He supplies a photograph of the white-coated stewards, most with 1970s’ bouffants, toasting the train on its arrival at Dover Marine. But when the last ‘up’ Golden Arrow arrived at Victoria in the early evening, ‘no one came to cheer … The Pullman cars were taken back empty stock to Clapham carriage sidings, then eventually to Brighton for disposal.’

It’s a good job Henry Maxwell did not live to see the ‘Family Bar’ of the Pride of Burgundy, with its TV and fruit machines, scampering children, tables loaded with bottles of Chardonnay, pints of lager, foaming cappuccinos in paper cups and bags of crisps. If he had done, and he’d seen me in it, I’m sure he would have disapproved of me as well. ‘The holiday starts here,’ observed the man sitting directly next to me, as he observed the raucous scene. His name was Steven House, and he too was a foot passenger. He now lives in Antwerp, but he’d grown up in Aylesham, Kent, and as a boy he had often waved at the Golden Arrow from various Kentish fields. He was returning from visiting his mother, who still lives in Kent. He had travelled at short notice, and this was a cheaper way of doing so than Eurostar.

I told him about the Canterbury, and said that I thought the Pride of Burgundy could do with an oak-panelled smoking-room, or a Parisian-style restaurant. ‘There’s always the Club Lounge,’ said Mr House, who knows a lot about crossing the Channel. The words seemed familiar. I checked my ferry voucher. I had grandiosely requested ‘first-class all the way’ when booking my tickets, and while there is, strictly speaking, no class system on a cross-Channel ferry, I saw that I had paid a small supplement entitling me to use this ‘Club Lounge’. Making my excuses to Mr House, I went in search of it.

Opening the door, I entered a plush, pinkish room … and a Golden Arrow sort of world: unquestionably middle-class people sat at low tables eating prawn mayonnaise sandwiches, or something that turned out to be called ‘salmon timbale’, while talking quietly, or reading Great Golf magazine, copies of which were available on a complimentary basis, along with tea, coffee, soft drinks and snacks. I decided against ordering a sandwich – unwisely, as it would turn out – but took two packets of complimentary peanuts and gave one to Mr House when I returned to the Family Bar.

He was looking through the window. The sun was glimmering on the sea, and I thought of what the Maltese gent had said: ‘I’d rather be on the sea than under it.’ As we approached the dock, Mr House began trying to locate the site of the old Calais Maritime railway station …

On arrival at Calais, Arrow passengers would have been ushered through Calais Maritime (counterpart to Dover Marine) and onto the Flèche d’Or, which would have wound its way through the second Calais station, Calais Ville, in the middle of the town, before proceeding to Paris. Calais Maritime had been an elegant château-like building, which was flattened by bombs in the war, and replaced by a single-storey concrete building. It was demolished in the mid-’90s. ‘I think it was over there,’ said Mr House, as we disembarked from the Burgundy at nearly mid-day (1 p.m. French time). I tried to picture the station, which I myself had used as a boy, but I could conjure no image to replace the bleak modern reality, which is a vast hinterland of car parks.

My father says of Calais Maritime, ‘It always made me anxious. Every time we got off the ferry there’d be half a dozen trains waiting, and this cacophony of announcements in French. I never knew which one to board, and if you got on the wrong one, you ended up in the wrong country.’

For now, I was faced with the question of how to get to Calais Ville, from where my train was due to depart. I didn’t quite trust the connecting bus on this side. I had once waited half an hour for it at the ferry terminal, and I recall a languid Frenchman, a member of the port staff, who was in no hurry to go anywhere, lighting a cigarette and saying, ‘Why not take a taxi?’ It had arrived eventually, and I had made my connection at Calais Ville with a minute to spare. ‘If the bus doesn’t come,’ said Mr House, ‘we can walk it – takes about twenty-five minutes. You just keep the station clock tower in sight.’

But the bus was already waiting outside the ferry terminal. On boarding with Mr House, I realised that two of our fellow foot passengers were Americans, father and son. I asked them why they’d come by this route: ‘To see the White Cliffs of Dover,’ said dad, ‘also Calais, the last part of English territory given up during the Hundred Years War.’ In view of this knowledge of English history, evidently better than mine, it seemed likely they’d heard of the Golden Arrow. They hadn’t.

‘Sounds great, though.’