VIII

Bertram Visits Snare Forks

Adoniram’s uncle kept his foot hard down on the accelerator, for they had a long way to go, and they wanted to get home that night. The car leaped and bounced, and Ronald had to hang on tight and didn’t have a chance to do much thinking. He did enough, though, to decide that there really wasn’t anything to worry about. They had been going about two hours when Jacob came back. He signaled through the window, and Ronald let him in.

“I’ve talked to the animals,” said the wasp, “and they think that if you’ll stick with Bertram for just a few days, then you can escape and drive him back home. And probably Adoniram’s folks will get discouraged if he runs away again and let the Beans adopt him.”

“That’s all right,” said Ronald, “but I haven’t been married very long. One can’t desert one’s bride practically at the altar, you know, and go careering off in search of adventure.”

“Oh, I talked to Cackletta,” said Jacob. “She said she thought it was just wonderful of you to do this for Adoniram. She said she thought you were terribly brave. And you’d have such marvelous adventures to tell her about when you got back.”

There never yet was a rooster that couldn’t be flattered into doing something he didn’t want to do. Ronald puffed out his chest and tried at the same time to look modest, which is practically impossible. “Oh, I say!” he said. “Nothing brave about it, you know, old man. Line of duty. Have to do these things, what? Thought it was brave of me, eh?”

“Brave as a lion.”

“Silly little thing!” said Ronald tenderly. “Well, well, you can tell them that I shall try to live up to their expectations. Never fear, I will return triumphant.”

“England expects every man to do his duty, eh?” said Jacob. “That’s the stuff. Well, I must push off. If we don’t hear from you inside a week, we’ll know you can’t get away, and Jinx said in that case don’t worry—the gang will come after you. So long.”

Ronald had talked so bravely that he began to feel brave—which is something that quite often happens to people. At six o’clock Adoniram’s uncle and aunt stopped at a restaurant and had supper. They told Bertram that he couldn’t have anything to eat, but must stay in the car. But as Bertram never ate anything anyway this was no punishment. As for Ronald, he had a box of corn meal in the control room, so it wasn’t any hardship for him either.

It was after midnight when they got back to the house by the river. There was some discussion whether they should spank Bertram then or wait until morning, but they were both pretty tired so they decided to postpone it, feeling they wouldn’t do justice to it unless they were fresh. So they sent him down to the barn to bed.

When Ronald got Bertram into the barn he opened the door and hopped out and stretched his wings, and at first he thought he would spend the night perched on a tree outside, for the night was warm and close. But then he decided he had better not, for if he overslept after his long ride, and Adoniram’s uncle came down to the barn before he could get back into the control room, they might think Bertram was sick and send for a doctor. And then of course they would find out that he was a clockwork boy, and not Adoniram at all.

So Ronald had Bertram walk over to a window and turn his back to it, and then he opened the little door so the breeze would blow on him, and went to sleep. And Bertram stood up all night.

Early in the morning the rooster was awakened by a shout of “Adoniram!” He shook the sleep out of his eyes and pulled the right levers, and Bertram turned around and walked out of the barn.

“Oh,” said Adoniram’s uncle, “you’re up and dressed, are you? Wonder you wouldn’t answer when you’re called.”

“I’m sorry, sir, I didn’t hear,” said Ronald.

“Eh? What’s the matter with your voice, boy?” said the man, staring at him in surprise.

“Got a cold,” said Ronald, and, to prove it, wiped his sleeve across his nose.

“Use your handkerchief!” said the man.

“I haven’t got one,” said Ronald.

“That’s a fine excuse, that is,” said the other. “Well, take the hoe and go down and hoe the potatoes for an hour while I have my breakfast. Then come back here and I’ll give you your spanking. Then your aunt will give you your breakfast, and then she will spank you, and then you can go back to the potatoes.”

“Yes, sir,” said Ronald, and Bertram got a hoe and strode off toward the potato patch.

Adoniram’s uncle looked after him curiously. “Wonder why he walks so stiff,” he said to himself. “Can’t be rheumatism at his age. Well, maybe a good whipping will limber him up.”

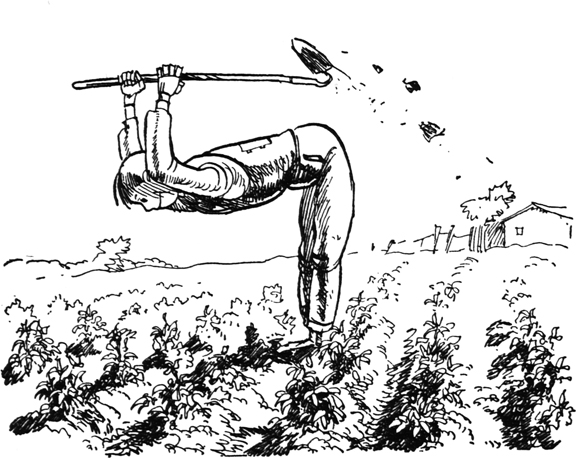

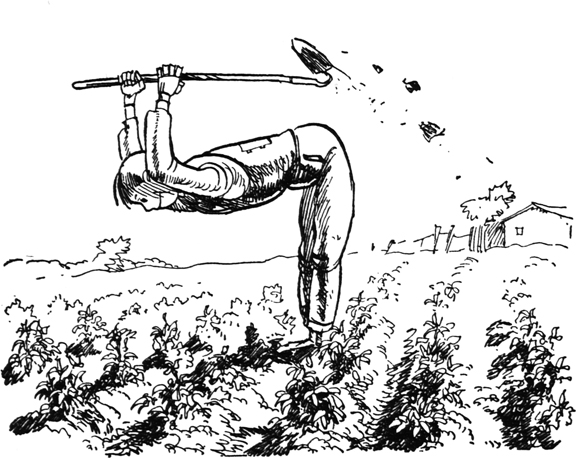

Bertram hoed for an hour, and as he never had to stop for a rest, he did as much hoeing as four men would have done in the time. The hoeing had been rather fun for Ronald, but “I don’t know,” he said as he went back to the house for his spanking; “if Bertram does as much work as that they’ll never let him get away again.”

“Now, young man,” said Adoniram’s uncle, “get across my knee.”

Bertram knelt down and leaned his weight on the man’s knees.

“Quit making that clicking noise,” said Adoniram’s uncle. “Good land, you’ve put on a lot of weight. Been havin’ too much to eat, likely. Well, we’ll see if you get any fatter on bread and water.” Then he started to spank.

But he didn’t spank very long. In fact, after the first spank he gave a yell and shook his fingers as his wife had done after she had slapped Bertram. Only it hurt him worse, because his hand had come down on one of the iron hinges that joined Bertram’s legs to his body.

“Get up, consarn you!” he roared. “I’ll teach you to put bricks under your clothes. Luella, where’s the horsewhip?”

So Adoniram’s aunt brought the horsewhip, and Adoniram’s uncle whipped Bertram until he was pretty nearly exhausted. And Ronald made whining noises every time the whip fell, so it would sound as if it hurt. Ronald enjoyed himself quite a lot at first. But then he remembered that this whipping was really intended for Adoniram, who was his friend, and he got mad. At first he thought he’d make Bertram hit Adoniram’s uncle, but he was afraid that they might put him in jail if he did that. So he thought a minute, and then he remembered how Uncle Ben had adjusted the microphone, so he turned it up to make it louder, and yelled: “Ouch! You’re hurting me! Ow-ow-ow!”

Well, you know what happens when you turn the radio on too loud. That was just what happened to Bertram. Adoniram’s aunt and uncle yelled and ran outdoors, and farmers plowing on distant hillsides and housewives washing up the breakfast dishes stopped work and looked up and said: “My goodness, somebody bein’ killed? Over toward the Smith place, seemin’ly.”

Ronald bawled for quite a while, but at last he stopped and went to the door. Adoniram’s uncle and aunt were whispering to each other and they were as white as two sheets. They stopped when they saw him.

“Don’t you ever make such a noise again,” said Adoniram’s aunt coming toward him. “My goodness, what will the neighbors think?”

“We won’t whip you any more,” said Adoniram’s uncle.

So Ronald turned the microphone down and said: “All right.”

“Go in and eat your bread and water,” said Adoniram’s aunt.

“I don’t want anything to eat,” said Bertram, and he picked up his hoe and went back to the potato patch.

But this time he didn’t do any work at all. He leaned the hoe against a tree and sat down in the grass. Pretty soon he heard a shout: “Adoniraaaam!” But he didn’t move. And presently Adoniram’s uncle came along.

“Get up,” he said, and when Bertram still didn’t move, Adoniram’s uncle kicked him. And, of course, hurt his toe.

“See here boy,” he said when he had stopped hopping around, “there’s some things you’ve got to understand. One is, you’re going to work on this farm like you used to do. And the other is, if you try any more monkey business of putting stones in your pockets, I’ll give you a beating you won’t forget.”

Bertram turned the microphone up again and said: “What?” in a voice that could have been heard six miles.

“Quiet!” said Adoniram’s uncle, looking around apprehensively. “All right, I won’t whip you again. But you’ve got to do your work. If you don’t, you just won’t get fed, that’s all.”

“That’s all right with me,” said Bertram.

“What!” exclaimed Adoniram’s uncle. “You dare say that to me?”

But Ronald had learned how to talk to him. He turned the microphone up again and bawled: “I won’t eat and I won’t work!” And Adoniram’s uncle put his hands over his ears and ran.

“Well, what happens next, I wonder?” said Ronald to himself. But what happened was a pretty big surprise. For Bertram hadn’t been wound up since the morning of the previous day. And suddenly he ran down and fell over flat on his back.

Ronald was in real trouble now. For the little door he got in and out by was in Bertram’s back, and he couldn’t open it. He got hold of the key that wound Bertram up, but he wasn’t strong enough to turn it. And then he thought for a while, but that didn’t do any good either, because the only thought he had was that he had been a fool to come.

But after Bertram had lain there for an hour or so, Adoniram’s aunt came out to see if she couldn’t shame him into working.

“You big lazy hulk,” she said, “aren’t you ashamed of yourself, lying there with all this work to be done!”

“I’m sick,” said Bertram weakly. “I can’t get up.”

She stared at him, frowning. “Well, what do you expect,” she said, “if you won’t eat your breakfast?”

So she stood and argued with him for a while, and then as he still said he was too weak to get up, she went and called her husband.

“If he’s really sick,” she said, “we must get him in the house.”

So Adoniram’s uncle leaned down to get hold of him.

“No, no, it hurts,” said Bertram. “Don’t touch me.” For Ronald was afraid that if they tried to carry Bertram, they’d find out what he really was.

“Have to call a doctor, I guess,” said Adoniram’s uncle.

“Nonsense,” said his wife. “Spend good money on doctor’s bills for a worthless lump of a boy? I guess not! I guess you wish you’d let those people adopt him now. What good is he?”

So they argued for a while, and at last agreed to call the doctor.

Dr. Murdock was a red-faced old gentleman with white whiskers and glasses that kept falling off. “Well, well, well,” he said when he saw Bertram, “what have we here?” And he felt of Bertram’s wrist. “Pulse very feeble,” he said. “Looks like starvation to me.” And he stared very hard at Adoniram’s uncle and aunt.

They both started explaining at once, how the boy had refused his breakfast, and how they always fed him well, and how good they were to him.

“Yes, yes, yes,” said Dr. Murdock impatiently. “I know all about that. I heard him yelling this morning when I stopped in to see old Mrs. Scrunch’s rheumatism. Guess you licked him a little too hard, eh?”

Then he bent down and put his ear to Bertram’s chest to listen to his heart.

“Doctor,” whispered Ronald. “I want to tell you something. Send them away.”

Dr. Murdock started violently when he heard this whisper coming out of a chest where a heart should have been beating. But like most doctors, he was never very much surprised at anything he found inside his patients, and when he had recovered his glasses, which had fallen off when he jumped, he sent Adoniram’s uncle and aunt away. They didn’t want to go very much, but he made them.

“Turn me over, doctor,” said Ronald, and with a good deal of heaving and grunting, and remarks about what a husky boy Adoniram was, to be sure, the doctor turned him on his face. And Ronald opened the door and came out.

Well, this did surprise Dr. Murdock, for he had never found a rooster in any of his patients before. “Upon my soul!” he exclaimed. “A rooster!”

“Yes, sir,” said Ronald. And then he told the doctor the whole story.

“Humph,” said the doctor when he had finished. “Well, there’s one thing I’ll say: you’re the easiest case to cure I ever had.” And he took hold of the key and wound Bertram up. “How long do you plan to stay here?”

“I don’t know,” said Ronald. “I expect I could go back most any time now. I don’t suppose they’ll come for Adoniram again, do you? After this?”

“I shouldn’t think so,” said Dr. Murdock. “I should think they’d be glad to have this Mr. Bean adopt him. But I don’t know. They’re mean people. I think if you could stay a few more days, so they will realize thoroughly that there’s no more work to be got out of you—and maybe you’ll think up some other ways of being disagreeable. They’ve mistreated that boy shamefully. They deserve any unpleasantness you can make for them. And, of course, I’ll tell them that I have to see you every day for a few days—so I can come over and keep Bertram, here, wound up, you see?”

So then Ronald got back into the control room and showed Dr. Murdock a few of the things Bertram could do, and then the doctor went up to the house.

Adoniram’s aunt and uncle were pretty mad at having to pay the doctor, especially as he said the boy oughtn’t to do any work for a while. They tried to make Bertram do some more hoeing that afternoon, but he just refused and went off and took a walk. The next day was about the same, and in the afternoon Dr. Murdock came and wound Bertram up. And that evening Adoniram’s uncle and aunt came down to the barn.

They came very quietly, an hour after Bertram had gone to bed, but Ronald heard them coming. Roosters have small ears, but they don’t miss much. Bertram was standing by the window again, but Ronald had him lie down quickly, and Bertram’s adjustable eyelids clicked shut. And when Adoniram’s aunt bent over to look at him, Ronald made sleeping sounds.

“Psst!” said Adoniram’s aunt, and Adoniram’s uncle rushed in with a lantern and a clothes-line and quickly tied Bertram’s arms tight to his sides while his wife knotted a towel over his mouth so he couldn’t yell.

“And now,” said Adoniram’s uncle, reaching for the whip, “get up on your feet, Adoniram. I’ve spanked you with hands and hairbrushes and basting spoons and I’ve licked you with shingles and carriage whips and dust mops and I’ve whaled you with straps and broom handles and yardsticks and old pieces of pipe. But after all that, you’re just the same stubborn, good-for-nothing, lazy lummox you always were. So I’m going to give you the most everlasting high-powered father and mother of a lambasting you ever had in your life. And then I guess you’ll do as you’re told. Take off your coat.”

Now Bertram couldn’t take his coat off when his hands were tied, and anyway Ronald knew that if he did, a lot of machinery would be visible. While he got Bertram to his feet he was wondering what to do. “I guess,” he said to himself, “that now is the time to take the doctor’s advice and be kind of unpleasant.” So as Adoniram’s uncle swung the whip back, Bertram just raised his arms, and the clothes line snapped like string and dropped to the floor.

“Look out!” yelled Adoniram’s aunt, and ran for the door. Her husband dashed after her, and before Bertram could follow they had slammed the heavy barn door shut and wedged it tight with a piece of timber.

“There,” shouted Adoniram’s uncle, “now we’ll see who’s master around here. You’ll stay there until you’re ready to do as you’re told.” And they both laughed nastily.

But Bertram walked up to the door and drew back his fists and punched—right, left, right, left—and each time a fist went splintering right through the planks. When they were pretty well weakened, he put his shoulder against them and pushed, and then he was out in the open, walking slowly along after his two persecutors, who were scuttling off toward the house.

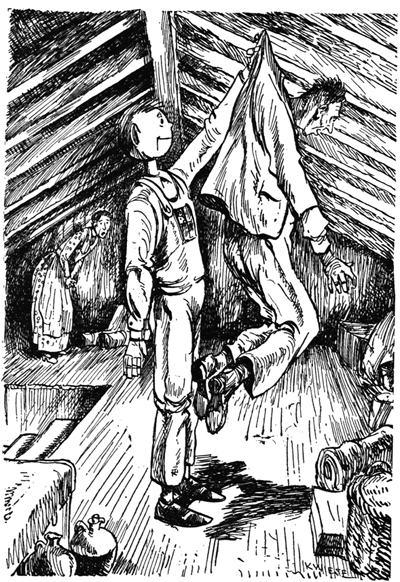

The front door was locked when he got to the house, but he just walked into it and it went down—bang! He heard a squeal of fright, and footsteps racing up the stairs. He followed them. Everything was quiet on the second floor. But all the doors were open except the one to the attic stairs. He kicked that down and went up the stairs—clump, clump, clump. And there, cowering behind a trunk, he found them.

He reached out one hand and caught Adoniram’s uncle by the collar and pulled him out. Adoniram’s uncle struggled and hit out, but he only hit Bertram on the nose and bruised his knuckles. He didn’t even chip the paint. And Bertram caught him by the waist and swung him up and hung him by the coat collar on a big hook that was screwed into one of the rafters.

“Let me down,” roared Adoniram’s uncle. “I was only whipping you for your own good, Adoniram. It hurt me worse than it did you.”

“I guess it did, at that,” said Bertram.

“Oh, don’t hurt him,” begged Adoniram’s aunt. “We’ll promise not to whip you again. We’ll do whatever you want us to.”

“We don’t want to make you do anything you don’t want to do,” said her husband. “We’ll even let those Bean people adopt you, if you say so.”

Well, this was just what Ronald wanted them to say. But he thought he’d have a little more fun before he left. “I don’t know,” he said doubtfully. “After all, you’re my aunt and uncle. I expect probably I’d better stay here.”

“But we’re not your aunt and uncle,” said Mrs. Smith. (I suppose we’d better call her that now, since she was really not Adoniram’s aunt at all.) “We really haven’t any claim on you at all, so if the Beans want you, for mercy’s sake go live with them.”

Ronald was pretty puzzled at this. You can see why. He was Ronald, pretending to be Bertram, who was in turn pretending to be Adoniram. And now Adoniram was somebody else.

“Well, then,” he said, “who am I?”

“There was a flood six years ago, almost as bad as the one this spring,” said Mrs. Smith, “and you came floating down on a barn. We rescued you. You were too little to know where you came from, but you told us your name was Adoniram. You said you had another name, beginning with R, but you wouldn’t ever tell us what it was. That’s all we know.”

“But didn’t you ever try to find my people?”

“How could we?” said Mrs. Smith. “We’re too busy to go traipsing around the country looking for them. If they wanted you, why didn’t they look for you themselves?”

“You wanted to keep me so I could work for you when I grew up, I guess.”

“Well, what if we did? We saved your life, didn’t we? And a fine, grateful boy you turned out to be! Well, go your own way. We’ll be glad to be rid of you.”

“Oh, stop talking,” groaned Mr. Smith, “and let me down. Let him go, Luella, and a good riddance.”

So Bertram lifted Mr. Smith down from the hook, and then they went downstairs and signed the papers that would let the Beans adopt Adoniram, and Bertram put them in his pocket and walked out of the house.

He went first to Dr. Murdock’s and told him the whole story, and Dr. Murdock said he’d make inquiries and see if he could find out who Adoniram’s parents really were. And then he wound up Bertram good and tight.

“You’ve got a long way to go,” he said, “and you’ll have to get wound up several times on the road, unless you’re lucky enough to get a lift all the way. So I’d advise you to appeal to a policeman when you find yourself running down. They’ll wind you up without any nonsense and you can trust them. Good-by and good luck.”

Ronald had pretty good luck. He had gone barely half a mile when he came up to a car at the roadside. There was a man sitting on the running board.

“Hello, boy,” he said. “I don’t suppose you know where I can find a jack around here, do you? I’ve got a flat tire, and no jack to lift the axle, and none of these cars that are going by will stop so I can borrow one.”

“I guess I can help you,” said Bertram. And he caught hold of the rear bumper and lifted the wheel clear of the ground. “I’ll hold it while you get your spare tire on.”

The man stared. “Great Scott, boy!” he exclaimed. “You ought to be in a circus. You ain’t human!”

“You’re right, I’m not,” said Bertram. “But hurry. I can’t hold this all day.”

So the man put the tire on, and in return gave Bertram a lift for about fifty miles.

After that, Bertram walked for a mile or so more, and then he heard a horn blowing continuously behind him, coming nearer, and a big truck passed him and then drew up at the side of the road. The horn kept on blowing, and the driver got out and began poking around under the hood. “Guess I can’t fix it,” he said disconsolately as Bertram came up. “I’ll have to let her blow. Don’t dare shut it off altogether and drive without any horn at all.”

“If you’ll give me a lift, I’ll be your horn,” said Ronald, and he turned up the microphone and said: “Oo-hoo! Oo-hoooo!”

“Gosh,” said the truckman, “that’s a trick and a half, that is. That’s odd trick and rubber. Get aboard, boy. I’ll take you anywhere this side of Albany.”

So Bertram got aboard. When the truckman wanted to pass anybody, he just said: “Horn,” and Ronald would blow. And in between whiles they talked. The truckman wanted to learn how to make the horn noise, because he said he was pretty good at imitations, but Ronald said he didn’t really know how he did it himself. Then the truckman did some of his imitations, and one of them was an imitation of a rooster.

“I can do a rooster myself,” said Ronald, and he crowed.

“Pretty good,” said the truckman. “Not bad at all. But listen, try to make it more like this.”

Late in the afternoon Bertram got down from the truck, and he was within three miles of home.

He thanked the driver, and then he said: “There’s just one thing. Do you still think your imitation of a rooster is better than mine?”

“Now listen, buddy,” said the man. “Your imitation is good, all right. But you need practice. I’ve been doing it for years. It stands to reason mine’s better.”

“All right,” said Ronald. “Now watch.” He turned Bertram’s back to the truckman, and then he stuck his head out of the little door and crowed. Then he shut the door and Bertram walked off up the hill road toward the Bean farm. But at the top of the hill he turned. The truck was still standing in the middle of the road, and seven cars were lined up behind it, blowing their horns to get by. But the truckman just sat motionless on his seat, staring after Bertram with his mouth open. And Ronald turned up the microphone and gave one last, trumpet-like crow, then waved his arm and went on over the brow of the hill.

And by and by the truckman shivered and threw in the clutch and drove on. But he never did any imitations again.