THE SORTIE OF THE PORT ARTHUR SQUADRON, JUNE 23RD.

THOUGH for the Japanese the events of June 15th had relieved the military situation they had done nothing to ease the strain on the fleet, but rather the reverse. The Imperial Staff was bent on pursuing the victory at Telissu by starting their long-planned concentric advance on Liau-yang. The idea was to deliver their decisive blow and secure the whole military situation before the rains set in and made the movement of troops impossible. If this was to be done there was not an hour to spare. But before the real movement could begin General Oku must be got forward into line with the other two armies, and until a supply base could be established on the coast in front of him he was at the end of his tether. At present, his most advanced depôt was at Pu-lan-tien, and it was being filled by the railway. As, however, no locomotives had been captured the trucks had to be moved by coolies, and this method was found to be barely sufficient for the current needs of the force. For an accumulation such as a further advance demanded General Oku had to look to the fleet, and it was for this purpose the supply base south of Kaiping had been surveyed.

To appreciate the situation it must be remembered that in certain cases, where the supply line is difficult or confined, before an army can advance any considerable distance in force a detachment must be pushed forward in order to seize some point on the line of the intended movement, at which supplies can be accumulated freely. Such was the case now.

Even so it was but a stop-gap. No permanent system that would be adequate both for General Oku and General Nogi could be organised till Talien-hwan was cleared of mines and a proper railway base established. This work was also thrown upon the fleet, and on June 14th Admiral Miura was called from the Elliot Islands base to take over entire charge from the Army Disembarkation Staff. His orders were to arrange for landing military stores, heavy guns, and railway material, to bear the whole responsibility for the transport work, to set up pumping machinery and make a repairing dock, to sweep and buoy the bay, and to lay out booms and erect observation stations for its defence. Till this work was well forward the establishment at Yentoa Bay had to be retained, and Admiral Togo had thus the prospect of three military bases to guard. Over and above this arduous work the time had come when the absolute isolation of Port Arthur was imperative. Apart from the exigencies of the coming siege Admiral Bezobrazov’s raid had demonstrated the need of cutting the place off entirely from communication with the Russian Headquarters, to prevent their arranging combinations between the two squadrons.

Moreover, it was still by no means certain whether or not Port Arthur was effectually sealed. When the deputation waited on the Minister of Marine he had told them it was, or at least that no ship bigger than the Novik, a third-class cruiser of 3,000 tons, could get out. The immobility of the battleships and larger cruisers had apparently confirmed this impression even in the fleet. Nevertheless, Admiral Togo at least believed that an attempt to break out was imminent. His information was that the Russians were working harder than ever at repairing the damaged ships, that the Tsar had sent an order that on no account were they to surrender with the fortress, and that before the end came they were to endeavour to get to Vladivostok or to escape to the southward to meet the Baltic Fleet.

The problem before him was therefore of no small difficulty. He had still to keep his battleships at the Elliot Islands and watch the port by cruiser sub-divisions in two-day spells with corresponding flotilla guards at night. All this with the work in support of the Army meant a considerable dispersal of force. How was he to have it concentrated at the right time and place if the enemy put to sea? The solution he adopted is contained in a General Order issued on June 18th.1 The former system of cruiser watch was retained, the morning rendezvous being 10 miles west of Encounter Rock, from which point the ships of the sub-division on duty would begin their day patrol. An hour before sunset they would steam southward and pass the night south and east of Round Island. In case of fog they were to anchor east of the meridian of Changzudo. If the enemy came out they were to fire 10 shotted rounds and make the “Urgency” cypher by wireless. If there was interference one cruiser was to proceed to the base at full speed. The ship which first sighted the enemy was to keep touch out of range, and attempt to delay an escape southwards by occasionally attacking their rear ship and their destroyers. All ships on blockade duty were immediately to gather the flotillas within reach and bring them up to make a vigorous attack on the enemy’s rear. Similar orders were given for the flotilla on guard whose point of refuge was now Kerr Bay, and one of its divisions was specially told off for communicating the news to the blockade ships and the base.

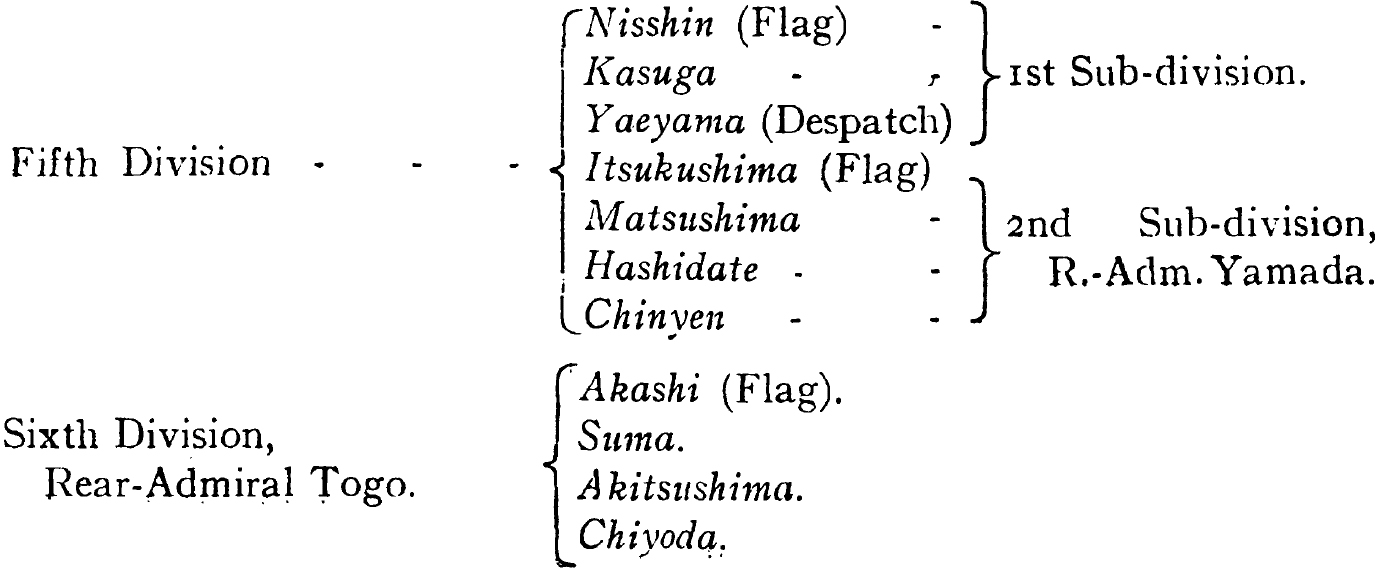

As for the battle mass, it was obvious that since the enemy’s destination was uncertain, and it was, therefore, not known what course they would take after leaving the port, it should be formed as close off their point of departure as was consistent with safety from mines. The concentration point chosen was Encounter Rock. There was still the danger that the enemy might succeed in stealing away before the concentration could be effected and it was to this eventuality the Admiral’s orders for the main force were directed. To appreciate them it is necessary to have clearly in mind the constitution of his fleet as well as its organisation which had been considerably modified. The squadronal arrangement is still traceable.2 Under the Commander-in-Chief’s immediate direction were the four remaining battleships and Admiral Dewa’s Division. This, which still formed the Third Division of the fleet, now consisted of the two armoured cruisers, Yakumo (Flag) and Asama, with the three second-class cruisers, Chitose, Takasago, and Kasagi. The Second Squadron, comprising the Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Divisions, was still under Admiral Kataoka and his flag was now in the Nisshin. This ship with her sister armoured cruiser Kasuga, which, having completed the repairs to her ram, had rejoined from Kuré on the 12th, and the small cruiser Yaeyama formed his first sub-division. The second, consisting of his original division, namely, the old battleship Chinyen and the three old cruisers Matsushima, Hashidate, and Tsukushima, was under Admiral Yamada with his flag in the last-named. These two sub-divisions formed the Fifth Division of the Fleet. The Sixth under Rear-Admiral Togo was unchanged and so was the Seventh or coast-defence division under Admiral Hosoya.2

For the battle mass neither the Yamada Sub-division nor the Seventh Division was available, Admiral Yamada being charged, if the enemy came out, to guard the Elliot Island Base and Yentoa Bay, while Admiral Hosoya with his coast-defence vessels and gunboats guarded the transports. The arrangement then, if news came that the enemy was actually escaping south, was that Admiral Dewa with two divisions of destroyers was to proceed as quickly as possible towards Shantung Promontory; Admiral Kataoka with his two armoured cruisers and the Sixth Division and three divisions of destroyers would make for a point 15 miles east of Shantung Promontory; and the Battle Division with one division of destroyers and one of torpedo-boats would head S. by E.

![]() E. for a position 28 miles W.N.W. of Modeste Island in the Mackau Group off the south-western extremity of Korea. This was the direct course for the Tsushima Strait and would carry him about 30 miles east of Shantung. In this way the narrows between Shantung and the Sir James Hall Islands, which were less than 100 miles wide, would be sufficiently well covered to ensure contact before the enemy reached open water. The general instructions were that any division getting contact during the day was to fight a delaying action till the divisions astern could get up; if by night, the divisional flotilla was to attack vigorously. The meaning of this was, that as Port Arthur and the Elliot Islands were almost equidistant from Shantung, the Russian Squadron, should it come out at night, would be able to pass the narrows before the Japanese Battle Squadron unless it were checked. But as Admiral Togo believed he had two or three knots’ superiority in speed, he calculated on reaching Modeste Island before his enemy and engaging them before they could enter the Tsushima Strait.

E. for a position 28 miles W.N.W. of Modeste Island in the Mackau Group off the south-western extremity of Korea. This was the direct course for the Tsushima Strait and would carry him about 30 miles east of Shantung. In this way the narrows between Shantung and the Sir James Hall Islands, which were less than 100 miles wide, would be sufficiently well covered to ensure contact before the enemy reached open water. The general instructions were that any division getting contact during the day was to fight a delaying action till the divisions astern could get up; if by night, the divisional flotilla was to attack vigorously. The meaning of this was, that as Port Arthur and the Elliot Islands were almost equidistant from Shantung, the Russian Squadron, should it come out at night, would be able to pass the narrows before the Japanese Battle Squadron unless it were checked. But as Admiral Togo believed he had two or three knots’ superiority in speed, he calculated on reaching Modeste Island before his enemy and engaging them before they could enter the Tsushima Strait.

It must not be assumed, however, that the Admiral’s dominant idea was to bring about a decisive action. In the concluding paragraph of the instructions he left the question in no doubt. “The above orders,” he wrote, “explain what is intended to be done if the enemy come out. But the object of our strategy is to prevent them from escaping. Our blockading division should always bear this in mind and intimidate the enemy by letting them see our ships.” His hope clearly was, firstly, to deter them from coming out by a constant display of force; and, secondly, if they did put to sea to stop them by massing his whole force at Encounter Rock. If, however, he found there was no time for concentrating so close off the port he would make sure of bringing them to action before they could leave the Yellow Sea or get touch with the Vladivostok Division.

Of the result of a battle there was little doubt in his mind. So far as our information goes the Japanese at this time were confident that the Russians could not possibly have more than one of their damaged battleships ready for sea, and the whole plan appears to have been based on an assumption of superiority.3 This confidence is rendered the more striking by what happened two days after the above orders were issued. On the 20th, General Oku called for an escort to conduct his store ships to the Kaiping Base. The Imperial Staff was, in fact, informing all officers concerned that an advance on Liau-yang was to be made as soon as possible. General Kawamura, instead of pushing on towards Kaiping, was ordered to stand fast and collect 20 days’ provisions at his front. General Kuroki was to do the same, and it was to assist General Oku in forming a like advanced depôt that the services of the fleet were required.

In spite of the increased dispersal it entailed, Admiral Togo met the demand at once by removing the Sixth Division from Admiral Kataoka’s command and detailing it for the service. Rear-Admiral Togo’s four light cruisers, whose place in the intercepting plan was off Shantung, were thus withdrawn from the scheme and Admiral Kataoka had nothing but his two armoured cruisers and despatch-vessel to cover the area assigned to him. The draft on Admiral Togo was, therefore, no light one, and his decision to honour it was made no easier by a caution which he quickly received from the Naval Staff at Tokyo. “As the fate of Port Arthur is becoming exceedingly critical,” Admiral Ijuin telegraphed, “their fleet will certainly make a desperate attempt to break out. Although I am sure that you have fully prepared a plan to meet such a move, I beg, as a matter of form, that you will not send ships too far away from you so that in emergencies you can concentrate and send them all against the enemy.”

The telegram appears to have an obvious connection with the Army’s last demand. It may even be taken as indicating the kind of friction which on these occasions inevitably arises between a naval and military Staff and which requires skilful and constant lubrication. In this case, apparently, Admiral Togo was given a hint that, seeing what the naval situation was, no military demand must be permitted to prejudice his battle concentration—a principle which within fair give-and-take limits no one would dispute.

Whatever it meant the Admiral did not take advantage of the discretion it allowed him. With characteristic loyalty to his military colleague he let the order for the store-ship escort stand, and did his best to minimise the risk it involved. On the 22nd, the day Admiral Ijuin’s message was received, Rear-Admiral Togo, who had just come in from his spell of blockade duty, was given definite orders to proceed with the store-ships on the 24th to Gobo, where the depôt was to be established, and to assist in landing their cargoes.4 That day also the entrance of Port Arthur was freshly mined and Admiral Kataoka, as a further precaution, received orders to proceed off the port with his two armoured cruisers. He was also to take under his command the whole of the torpedo-boat flotilla and the Chinyen and Matsushima from his Yamada sub-division, and to make a powerful demonstration on the morning of the 23rd. Admiral Dewa would also be at hand to support, since he had just taken over the routine watch from Rear-Admiral Togo, with the Yakumo and two other cruisers and the usual attached destroyers.

It was always believed by the Russians in Port Arthur that the Japanese had means of learning every decision that was come to. It is interesting, therefore, to note that in the above dispositions and orders there is no trace of their having known that the Russians had completed the repairs of all their battleships and had actually resolved to put to sea. Yet so it was. We have seen how the various orders which Admiral Vitgeft received from the Viceroy up to June 16th had left him in some doubt as to what was expected of him. On that day—forty-eight hours before Admiral Togo issued his general orders—he called a Council of War and after full deliberation it was decided that the squadron should put to sea on June 23rd, when the morning tide would be full at dawn, but with what precise object is uncertain. It is only to be inferred from the surrounding circumstances.

The general effect of the last orders from the Viceroy, it will be remembered, was that Admiral Vitgeft was to regard Port Arthur as his base so long as it had a prospect of holding out and that he was to employ his fleet as part of the combination for its relief. This it was considered he would achieve if he could meet an inferior squadron of the enemy and defeat it; and at the moment the prospects of success seemed peculiarly favourable.

For some days nothing had been seen of the Japanese squadron and the landing of troops at Yentoa Bay appeared to be complete. Though the loss of the Yashima had been successfully concealed the further disasters of the Japanese were known and other ships were believed to have been crippled. Owing probably to the Kasuga having been sent in to Sasebo, an impression gained ground that possibly the bulk of their squadron had withdrawn for repairs or perhaps to watch Vladivostok. Admiral Vitgeft, however, distinctly states that he did not believe the roseate reports of the Viceroy’s Staff as to the weakening of the Japanese fleet, and in the circumstances it would seem that what he decided was to make a reconnaissance in force to clear up the situation. But the evidence as to what his precise plan was is by no means clear. He himself in his subsequent report to the Viceroy explained it as follows5:—“The plan of my intended movements was to steam out to sea for the night at some distance from the destroyers. Calculating that the enemy’s fleet was much weaker than ours (in accordance with the Staff information) and that it would be scattered at various points in the Yellow Sea and the Gulf of Pe-chi-li, I intended during the day [meaning presumably the next day] to proceed towards the Elliot Islands and seeking out the enemy to attack him as a whole or in detail.” This would scarcely appear to be the whole truth. The Admiral’s official report states there were constant conferences of Flag Officers and Captains at which “the possible plan of operations was discussed and elucidated.” Captain Bubnov is more explicit, and although he does not appear to have been present at the discussions he probably wrote with authority.6 His statement is that “after a long deliberation it was decided to put to sea for a three days’ cruise, to examine the Elliot Islands, and to engage the enemy should he be met with in suitable force.” Further, there is the general order which the Admiral issued to the fleet on the 20th saying that the squadron was about to put to sea by order of the Viceroy “in order to assist their comrades ashore in the defence of Port Arthur.” Nowhere is there any suggestion of an attempt to break through to Vladivostok. What is indicated is a design to run out to sea clear of the Japanese destroyers for the first night and then by doubling back to strike a blow at the enemy’s base and deal with anything they found there or encountered on the way that did not seem beyond their strength.7

That strength, however, was not what it seemed even in material, for only one ship had her full armament on board. Of twenty-two 6-inch guns, seven 4.7, and forty-two 12-pounders lent to the army only three 6-inch had been returned. The Sevastopol was short of one of her 12-inch, the Pobyeda of eight 6-inch. In all eighteen 6-inch and twenty-three 12-pounders were missing, besides over fifty light guns. Added to this 600 men were ashore with the guns and searchlights and their numbers had to be made up from the small ships, naval barracks and reserve, and at the last moment the captain of the Pobyeda went sick. His ship was given to the captain of the Pallada and the Pallada to the commander of the mine-layer Amur, which had recently been disabled by fouling one of the sunken blockships.8 The confusion was further increased by a new Chief of the Staff in the person of Rear-Admiral Matusevich, who hitherto had been in charge of the blue-jackets ashore; while Admiral Loshchinski, who alone had shown real capacity for command, was by the Viceroy’s orders to be left behind. If then Admiral Vitgeft had any real intention of dealing with the enemy “as a whole” it cannot have been without very serious misgiving.

The main difficulty in carrying out the programme lay in the Japanese mines. Vigorous sweeping operations had been going on for some time and destroyers were out every night to keep off the enemy’s mine-layers. This work had been so successful that a passage 700 feet wide had been cleared to a distance of seven miles, as well as an anchorage in the roadstead between their own defensive minefields. But it will be remembered that when Admiral Togo decided to detach the Sixth Division into the Gulf of Liau-tung at General Oku’s request, he had taken the precaution of ordering new minefields to be laid off the port. Before daybreak on the 22nd this had been done, in spite of the fire of the Russians batteries and guard boats. The next night as Admiral Vitgeft was preparing to weigh the work was continued. But this time the mining party encountered two gunboats and two divisions of destroyers which had been sent out to keep the channel clear. A desultory action ensued in the dark in which two Russian destroyers were damaged. They believed nevertheless they had driven off their enemy. But it was not so. While the fighting was going on two picket-boats fitted with mining gear had stolen in so close as to be inside the searchlight beams and were able unseen to lay a minefield just outside the Russian eastern field. Knowing nothing of this, Admiral Vitgeft had no ground for further hesitation, and at dawn on the 23rd he made the signal to weigh.

It was not till nearly 6.0 that the inshore Japanese destroyers on night guard detected the movement,9 and even then it was an hour before the morning haze permitted them to realise what it meant. Though an order had just been given for the leading boat in each division to be fitted with wireless, the gear had not yet been installed and the officer in command had to go off to Encounter Rock to find Admiral Dewa. The delay was serious. He did not reach the Yakumo till 8.0, and consequently Admiral Togo did not receive her “Urgency” signal till 8.20; but Admiral Kataoka had already started for his demonstration before the port with his two armoured cruisers, and taking in the signal he made straight for Encounter Rock. The armoured cruiser Asama had also left by routine to relieve the Yakumo and the other two ships of her sub-division, Kasagi, and Takasago, were just starting to join her. Still it must be long before anything else could move, and when Admiral Togo signalled to raise steam he did not expect to get away for an hour and a half.

While the Elliot Island base was thus starting into feverish activity the destroyers on guard, to their surprise, saw the Russians anchoring in the outer roadstead, apparently close to where the new minefield had been laid in the night. As yet all the ships had not come out, and when the next destroyer went off to report the full extent of the crisis was not known. According to the Russians themselves they had actually anchored in the midst of the new minefield and by a miracle had escaped injury. Fortunately for them the mines had been badly moored. Several came to the surface to give warning and the squadron was able to remain where it was in comparative safety till the whole area had been swept. It meant of course hours of delay—a delay on which Admiral Togo had probably counted.

Amongst the ships which had not appeared when the last destroyer came away to report were the three injured battleships. He was still, therefore, unaware of the full gravity of the situation, and could regard it as well in hand. One precaution, however, he deemed it necessary to take. The movement which General Oku had requested must be countermanded. Rear-Admiral Togo could not be spared. He was then at the Elliot Islands preparing to sail next day with the victual transports. They were ordered to stand fast, and the Rear-Admiral was sent away immediately with his division to Port Arthur. The necessity of cancelling this important operation affords a striking example of the influence of a “fleet in being,” that is, of a fleet long dormant which had come to life again, and the abandonment of the movement to Gobo was, as we shall see, only the beginning of the disturbance which its exhibition of activity inflicted upon the plans of the Japanese Imperial Staff. No other change was made, but to gain time for the battle concentration Admiral Kataoka, who with the Nisshin and Kasuga was already off Kerr Bay, was directed to carry on with every destroyer and torpedo-boat he could lay hands on. Two more of his demonstration force, both belonging to the Yamada sub-division, were already on their way. At Kerr Bay the Chinyen returning from patrol duty met the Matsushima which had just arrived from the Elliot Islands to protect the sweeping operations in the bay, and together they at once made for Cap Island. The rest of Admiral Yamada’s division was at the Elliot Islands, and left at 9.45 to take up the position south of Kwang-lo-tau to guard the base. The Commander-in-Chief did not get away till 10.30—over two hours after he had received the “Urgency” signal, and at 10 knots only he made for Round Island. Not till then, as he was moving out, did he know what it was he had to meet. By 11.0, so he said in his official despatch, he learned that, contrary to all expectation, the whole of the Russian battleships had made good their damages and that he would have to fight six with his four.

What the effect was on his mind we cannot know. All he tells is that he determined to try to lure his enemy out to sea. This was contrary to his standing order that flag officers were to show their ships in order to intimidate the Russians from coming out. But now they had come out, and it is only natural to assume that he was resolved if possible to strike them a blow of some kind. The idea of luring them to sea does not necessarily imply that he was seeking a general action. It was equally compatible with offensive mining or a flotilla attack after dark. Before leaving the base he had made arrangements for the picket-boats to lay mines off the port behind the enemy and his two torpedo depôt ships had been ordered to be at Round Island next morning. Of one thing, however, in view of the general orders he had given, we may be certain, that come what might, the enemy must not be suffered to leave the Yellow Sea, even at the cost of staking the issue of the war on a decisive battle.10

In any case the dispositions already made for a concentration required no change. Soon after 11.0 Admiral Kataoka joined Admiral Dewa, who was at Encounter Rock on blockade duty with the Yakumo and Chitose, and began carrying out his last order for a demonstration with the flotilla, while his colleague cruised slowly to the westward. Still the Russians did not stir; they were busy sweeping and sinking the mines they found. It was nearly 3.0 before all was reported clear and they ventured to weigh.

The course they steered was to the southward, and the Chinyen and the Matsushima having just reached Cap Island, were able to note it and report by wireless with sufficient accuracy. About the same time Admiral Kataoka had launched the massed flotilla on its intimidating demonstration. They found the enemy moving in line-ahead very slowly, preceded by a sweeping flotilla and its destroyer escort.11 These vessels were at once fired on by the leading Japanese boats, who, the Russians says, ran in “with great impudence” to molest them, an operation which scarcely endorses Admiral Togo’s alleged intention of “luring his enemy out to sea.” The Novik and two divisions of destroyers that formed their guard moved to oppose them, assisted by the fire of the cruiser Diana that was leading the line. The Japanese flotilla, having no similar support, was forced to retire.

The Chinyen, which had been at hand on observation duty, had gone off to report to the Commander-in-Chief, leaving the Matsushima to continue keeping observation, but this ship was some time in coming up. Admiral Dewa, however, who had been joined by the Kasagi and Takasago from the base, although too far out to see what was going on, could hear the firing, and about 3.45, as it seemed to increase, he sent in the Chitose with the Chiyoda, which had just joined him in company with the Asama. With his two armoured cruisers he then drew in himself.

The meaning of the continued firing was that as the Russian destroyers straggled in chase of their retiring enemy the Japanese had turned on them. Again the Novik advanced, but by 4.0 the first of the Japanese supporting ships had begun to heave in sight. Then for the first time the Russians divined they had something formidable in front of them and the chase ceased. As the retiring Japanese flotilla came in, Admiral Dewa slowly fell back, trying, it is again said, to draw the enemy southward, while the Kasagi and Matsushima hung on either flank to watch their movements.

Meanwhile the battle division having reached Round Island was holding on for Encounter Rock. Rear-Admiral Togo was already there and the fleet was in a state of concentration. There was still plenty of time. The Japanese believed that their flotilla demonstration had checked the sweeping, and the Russians were reported to be advancing very slowly with the same precautions as before. By 4.0 Admiral Togo had reached Encounter Rock, his battle mass was complete, and it was open to him to seek a decision. Did he do so, and if so was he right?

At the time he was highly praised for the restraint he showed in avoiding an action with a force which he had suddenly found was greatly superior to his own. This judgment is hard to follow. The Russians certainly believed it was they who were in inferiority. Measured by the ordinary tests there was no difference between the offensive power of the two fleets great enough in itself to tempt either side to hazard a decision. The Japanese had but four battleships to the Russian six, but they had four armoured cruisers to one, besides the Chinyen. Even without her the Japanese armoured line numbered in guns of 6-inch and upwards 139, while the Russians, deducting the guns remaining on shore, could only show 85. On the other hand, the Russians could oppose a primary armament of 23 guns of 10-inch and upwards against the Japanese 17. In cruisers and flotilla the Japanese were greatly superior. It is difficult to believe, therefore, that if Admiral Togo, with a more seasoned fleet and higher speed, avoided action it was because he felt himself decidedly inferior to his enemy.12

The facts on which we have to form an opinion are fairly clear. By about 5.30 Admiral Vitgeft was free to take what course he chose, and, considering that he had reached open water, he dismissed his sweeping vessels and began forming his line of battle. At this time Admiral Togo was steering W.S.W. so as to keep his battle division out of sight. This was obviously in accordance with his expressed intention of enticing the enemy further to sea, but whether to entrap them into a decisive action or to expose them to torpedo attack there is still nothing to show except the fact that there were not many hours of daylight left. At 5.30, finding that on a report from the Matsushima he had crossed the course of the enemy, he turned 16 points to E.N.E. A little later the Russians having formed their line of battle had moved off S. 20 E. (true) for Shantung Promontory, and being already over 20 miles from shore seemed determined to persevere. Their resolute attitude appears to have convinced Admiral Togo that an action must be fought and brought him face to face with the one condition which made it inevitable that a battle must be risked. The enemy were trying to escape. His whole strategy had been based on preventing their escape and to all appearance nothing but an action could stop them. At all events he now called on Admiral Kataoka, with the Nisshin and Kasuga from the Fifth Division, to join him, and at 6.0 he formed with them a line of battle numerically equal to that of the enemy. At the same time he signalled for the whole of the flotilla to prepare to attack. His precise intention is still not clear. He had within call no less than five divisions of destroyers and six of torpedo-boats, over 40 units in all. All of them report that they received the preparative at 5.50, and at 6.15, after the line of battle was formed, they took in the executive “to attack.” According to the Confidential History, however, the orders were “to keep contact with the enemy and attack after “sun-down if they came south or stopped outside the harbour.” There seems to have been some misunderstanding. The 3rd division of destroyers made off at once for the eastward of the harbour, intending to attack after midnight. One division of torpedo-boats made straight for the Tsesarevich, which was leading the Russian battle line. The rest remained in touch with the Mikasa, but why they did so is nowhere explained.

With his reinforced battle squadron Admiral Togo was still steaming E.N.E. back towards Encounter Rock “awaiting the enemy,” with his cruiser divisions on his starboard bow and quarter respectively. The flotilla or the greater part of it had hitherto been on his disengaged side, but when the preparative for attack was made, that is just before he formed his battle line it had taken station to port. By the time the new disposition was complete the Russians had been sighted in line-ahead some 8 miles N.W. of Encounter Rock still on the same course S. 20 E. Till 6.30 Admiral Togo held on to cross their course and then turned again 16 points to W.S.W. “By 7.5,” says the Confidential History, “the enemy were about 16,000 metres (9 miles) on the starboard beam. As they appeared to be coming south on a course which would cross ours at right angles, the First Division altered to S.W. so as to press on their leading ships,” which seems to mean that he turned away to avoid being crossed, and with the intention of securing by his superior speed an oblique concentration upon the enemy’s van and ultimately a position from which he himself would cross. Whatever else is in doubt it is quite clear that by this time the Admiral was determined to fight if the Russians held on, and beyond having altered more to the southward they showed no sign of giving way. At 7.12 he hoisted the battle flag, and then made the signal which shows how fully he grasped the responsibility of the decision he had taken. “This battle,” it ran, “will decide the fate of our country. Everyone will do his best.”

The signal made, he increased to battle speed—14 knots; but the setting sun was exactly behind the Russians and it was impossible to align a sight. Gradually, however, the Japanese drew ahead and got the enemy clear of the glare. By 8.0, that is about half an hour after sunset, they had closed to 12,500 metres (13,700 yards) and Admiral Togo altered two points to starboard back to his original course, in order to cross the enemy’s van. A night action seemed now inevitable, but it was not for the more highly trained fleet to avoid it. As Admiral Togo pressed on, the Russians gradually altered to starboard on a parallel course to avoid being crossed. The Japanese conformed by also inclining to starboard and thus the two fleets kept about the same relative positions. But the Japanese had the speed; the situation could not be prolonged; and sooner or later if the same tactics were maintained the Russians must be headed right off their course and through the Pe-chi-li Strait. Without a close action Admiral Vitgeft could not hope to run out to sea, and for close action the enemy had not been found “in suitable force.” The plan on which his cruise had been based was no longer realisable, while on the other hand he saw himself threatened with a danger he had no means of meeting. To him it appeared that part of the enemy’s flotilla was trying to get between him and his port, while the rest were holding off for a direct attack at nightfall. Before, then, it was too late he turned nearly 16 points in succession, and headed for Ping-tu-tau to avoid his own minefields. Then turning west till he picked up his leading marks he led the squadron back for the anchorage.

The explanation he afterwards gave the Viceroy was this. His plan had been frustrated “(1) owing to the lateness of our sortie; (2) owing to the enemy’s force being far superior; and (3) mainly owing to the large number of torpedo craft, against which I could only oppose seven and two torpedo vessels; and therefore I decided to steam back to Port Arthur in order to meet the night torpedo attacks in the roadstead and to act further according to circumstances.”

Seeing the retreat Admiral Togo immediately turned eight points together and with both cruiser divisions gave chase in an effort to close. Up to this time, notwithstanding the order to attack, he seems to have kept the bulk of his flotilla in hand, but now he let it loose.13 One or two of the divisions had already started directly the sun went down, and now they all headed for the shore west of Port Arthur to cut off the retreat. It was only for a quarter of an hour that the Admiral’s chase continued. Now that the sun had set, we are told, “he felt that offensive action must be left to the flotilla.” He had headed off the escape, and from the first he had clung to the principle that it was only to prevent an escape that the hazard of an action was justifiable. This decision was at least consistent; and in accordance with the plan on which he had been acting, he dispersed his various divisions to their night stations to guard against the possibility of the enemy’s renewing his attempt to break away. The battle division returned to Round Island while the two cruiser divisions were sent down to bar the approach to Shantung Promontory.14

For the Russians there was no thought of persisting in their plan. They were fully occupied in defending themselves against the swarms of torpedo craft that worried them through the night. The defence was entirely successful, and demonstrated again the unreliability of the torpedo for a primary operation. Still in this case the chances were all against the attack. The moon was at first behind the flotilla and brilliant enough to read by. There could be no concealment and the enemy were fully on the alert. The reckless speed, moreover, with which the squadron retired into waters strewn with mines surprised the Japanese, and only one or two divisions succeeded in attacking before it was at anchor and the nets were out. Had they all started when the executive was first made their chance would have been better. As it was they were nearly all held back too long. A rush of the whole mass as the enemy were anchoring was the only real chance, but no provision had been made for a concerted attack. Each division acted independently and even single boats took their own line. Some attacked as they came up, some waited for the moon to set, some did not find the enemy, some saw their chance foiled by other divisions and could not get in till daylight put an end to their efforts. Most of the boats came in from the eastward, ran along the Russian line, and after discharging their torpedoes escaped to the southward. Every boat as she attacked had to enter the zone of the shore searchlights, and thus each division as it attacked singly became the focus of a concentrated fire. The Russians were using not only their secondary armament but the turret guns as well. Blinded by the glare and the storm of spray the Japanese could neither judge distance nor lay their tubes. Officers who were present state that the spray bursts thrown up by the shells shone in the searchlight beams “like fountains of amber-coloured fireworks,” and that nothing could be seen through them. By the official reports, 67 torpedoes were fired at ranges which they put at from 400 (440 yards) to 1,500 (1,600 yards) metres, and not a ship was touched. The Russian range-finding positions ashore stated that no boat came within three miles of the fleet, but this must be an exaggeration, as a dozen torpedoes were found on the beach next day. Under the conditions of the attack the miracle is not that they missed but that they themselves escaped so easily. Though the Russians believed they had sunk two or three boats, only four were hit, and even these not severely enough to prevent their getting off. The escape of the Russians was scarcely less miraculous. They had run for the harbour at full speed in the dark and not through the channel by which they had left. Yet the Sevastopol was the only ship that suffered. She was the last but one in the line and the torpedo attack opened while she was still under way. In the excitement she edged away to port and fouled a mine which burst forward. A large rent was made in her side and two compartments were flooded, but she was able to get into shoal water in White Wolf Bay and next morning was towed safely in. There was no other mishap and by 11.0 a.m. the whole squadron had passed the gullet out of harm’s way.

The failure of the Japanese so far as an effective blow at the enemy’s fleet was concerned had been complete, but they found the truth hard to realise. The following morning when Admiral Togo had concentrated again, Admiral Dewa was sent in to ascertain the condition of the enemy. The torpedo depot ships had arrived and every preparation was made for a renewal of the attempt upon the ships in the roadstead. But by 1.0 o’clock it was known that they had all moved inside and that the opportunity had passed. The Admiral therefore returned to the Elliot Islands and the blockade resumed its normal course.

![]()

1 See post, Appendix I. 519.

2 The following table will give the organisation at a glance. The Seventh Division, being wholly devoted to coastal work, is omitted:—

FIRST SQUADRON—Admiral TOGO.

SECOND SQUADRON—Vice-Admiral KATAOKA.

3 Naval Attaché Report, I., page 103.

4 Gobo is about 6 miles west of Siung-yau station, which is 14 miles south of Kaiping station in lat. 40° 14 N., long. 122° 10′.

5 Russian Military History, Vol. VIII., Part ii., Appendix No. 15.

6 Recollections of Port Arthur, Chap. viii. The author was a naval officer and at this time was in command of the Naval Barracks ashore.

7 The only official statement that Vladivostok was the destination seems to be in the chronology issued by the Russian Naval Staff in which under June 23 is entered, “Attempt of the 1st Pacific Squadron to break through to Vladivostok.”

8 Admiral Vitgeft’s Report ubi supra.

9 It was 5.5 by Russian time. Japanese time is here used throughout.

10 The expression “luring the enemy out to sea” is of much interest, for there is reason to believe it should not be taken too seriously. It recurs constantly in connection with the battle of August 10th, and then as well as now Admiral Togo certainly did his best to head the enemy back. It may be conjectured the phrase was intended for home consumption, as an explanation of why he did not comply with the extravagant expectations of his countrymen and fall at once upon the enemy and destroy them. It probably means no more than that he did not consider the situation favourable for a close action.

11 The sweeping flotilla was composed of 6 steam hoppers, 2 harbour launches, 2 steam boats, and 6 destroyers.

12 The actual figures are as under:—

13 The Japanese Confidential History is confused on this point. In Chapter XII., Sec. i., p. 384, it says: “At 8.20 Admiral Togo ordered the destroyer and torpedo-boat flotillas to make a combined attack.” In Section ii., subsec. 1, p. 386, it says between 8.0 and 8.17 “offensive action was relinquished to the torpedo craft.” In Section iii, relating to the flotilla, it says, p. 392, all got the signal to attack at 6.15; but only the 3rd destroyer division went off at once apparently. The rest started about 8.15 after the enemy turned. The torpedo-boat divisions that were with the battle fleet did the same. The explanation may be that they were all hovering near the battle fleet waiting for a chance or that they took the signal to attack to mean “after dark.” None of the boats mention a second order after the Russians turned back.

14 Admiral Dewa’s position was 58 miles S.E.

![]() E, and Rear-Admiral Togo’s was 45 miles S.

E, and Rear-Admiral Togo’s was 45 miles S.

![]() E, of Encounter Rock,

E, of Encounter Rock,