Raoul Hague was born Haig Heukelekian in Constantinople in 1905 and died in Woodstock in 1993, and within that 88-year span he mastered what Constantin Brancusi called “the art of reanimating matter” (direct carving). Hague came to direct carving in his twenties, working with William Zorach at the Art Students League in New York. One day the sculptor John Flannagan (who hewed Woodstock’s Maverick Horse, symbol of the Maverick artists’ colony, out of an 18-foot-high standing chestnut stump at about this time) took Hague to a stone yard in Brooklyn and taught him to pick out the best stone for carving. Hague lugged a choice block of limestone back to his third-floor walk-up studio and whaled away at it all night with a hammer and chisel, while Flannagan watched, drank, and read the paper. In the morning, Flannagan said, “Well, that’s it. That’s your life. You are a sculptor.” And Hague was, for the next 68 years.

In the City, Hague carved stone in the summer (producing stone sculptures for the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration from 1935 to 1939) and wood in the winter, but when he moved up to Hervey White’s domain on Maverick Road in Woodstock for good in 1943, he found it difficult to get good stone (the local bluestone, he said, was “impossible to work”), so he began to work with wood all year round. Large tree trunks were plentiful in Ulster County, but one had to know how to get them. Hague’s friend the painter Holly Hughes tells of driving Hague all over the county scouting for old trees of sufficient girth and compelling character that were dead or dying or otherwise slated for felling. Hague remembered the locations of choice trunks by assigning them place-name titles: Shandaken, Peekamoose, Onandaga, Otsego Falls, Meads Mountain Meadows, Wallkill Walnut.

Once secured, these massive trunks (often weighing 600 pounds or more) were hauled back to the little brick and log house on Maverick Road and hoisted through a large door into Hague’s 10-by-15-foot studio. In order to clear the doorway, the selected trunks had to be less than 42 inches in diameter, and not more than 6 feet 4 inches in height after trimming. Hague cut away the largest pieces first with chainsaws, then used chisels and finer tools for the close work, sometimes taking six months or more to free the forms he saw within.

The work was both physically and aesthetically demanding. Hague faced each raw chunk of wood anew, remaking himself each time in the unpredictable reciprocity of direct carving. The beginning of a piece, he said, was “very cruel.” Each trunk presented different problems and required a different approach. One had to listen closely (with the eyes) to know what was required. Trying to force anything was disastrous. “I consider the wood has got half of the relationship with me,” Hague said. “I cannot dominate the material. It is a very close association.”1

Hague chose wood as his sole material, of course, for reasons other than its ready availability. As Ionel Jianou wrote in describing the relative values of Brancusi’s materials: “Marble lends itself to the contemplation of the origins of life, while wood lends itself more easily to the tumultuous expression of life’s contradictions.”2 Wood is resistant yet malleable, obdurate yet yielding, consistent yet variable. Its contradictions are resonant and generative in relation to human will. In Hague’s early years, the transformations of the trunks were more forceful, and the results often more figurative. Toward the end, the relation changed, so that more of the tree showed through. In his last years (he worked right up to the end), he listened more and asserted less. He became less concerned with finish, letting the tool marks show along with the irregularities of the wood. The forms became less labored, more spontaneous and raw. Reviewing Hague’s show at Lennon, Weinberg Gallery in December 1988 (when Hague was 83) for the New York Times, Michael Brenson wrote: “What is so striking about these works is the sense that he does not so much carve as listen. When he gets it right, the sculptures seem to have revealed themselves and shown him what they wanted to be…. When a piece of wood does finally speak, it seems to reveal itself all at once, in a hurry. The result is sculpture that is patient and impulsive at the same time.”3

Another of the active contradictions that is repeatedly and sumptuously explored in Hague’s work is that of masculine and feminine, what James Joyce called “the He and the She of it.” In the shifting grain and textures of the wood, in the dichotomous branching and successive forking of the trunks, Hague found fertile ground for his explorations. The forms are set in erotic tension and release, and this movement drives the most abstract later works as much as it does the earlier torsos. One experiences these works with one’s whole body, or not at all.

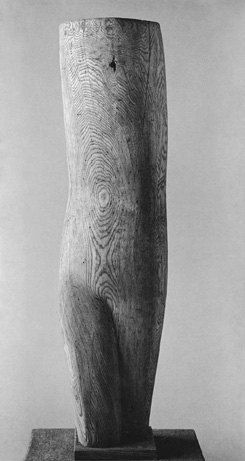

The chestnut torso from 1946, shown on the following page for the first time in nearly 40 years, is a work of exquisite torsion and balance. When Hague carved this piece, he had just given up carving in stone, and was beginning to find all the tension and potential he needed in wood. He liked carving chestnut, but couldn’t get it in large enough pieces, so most of his carving from this point on is in walnut. But in this torso, you can see the dawning of a new engagement with his material. The strong circular grain radiates out from a linked solar plexus and mons veneris, and Hague responds by twisting the entire sculpture the other way, around the vertical axis—legs crossing demurely below as the upper torso lifts and torques the other way. In these turnings, the torso comes alive.

Chestnut Torso (1946), photographer unknown; courtesy of Lennon, Weinberg Gallery, New York and the Raoul Hague Foundation

Jill Weinberg Adams has pointed out that this sculpture from 1946 may be the first instance of Hague engaging directly with the whole form of a tree trunk: its shape, grain, texture, scale, and movement. The balance achieved in this sculpture, between the assertions of the material and the will of the artist, showed Hague a way forward.

When Hague’s work was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 1956, Leo Steinberg wrote that Hague’s sculptures were “more concretely physical, far less involved with ideal essences than Brancusi’s…. They are stilled and collected and content in their own mass, without attempting to suggest the dynamics of growth, or potentials of space penetration.”4 Even though most of Hague’s sculptures are roughly the same size, some of them do fool the eye, suggesting a monumentality far greater than their actual dimensions—from the centrifugal spread of Peekamoose, to the forceful truncations of Onandaga, to the gravitational compaction and concentrated mass of Wallkill Walnut.

Steinberg recognized that Hague’s early works did not attempt to imitate “the superficial look of antique art, but the great surge and sinuous torsion of a stub of body.”5 Though Hague eventually moved away from the more explicit torsos, his sculptures remained thoroughly embodied. What we have in the end are no longer trees, but discrete somatic dialogues of an extraordinary kind.

In his own physique, Hague appeared to be all trunk and no limbs. The Woodstock historian Alf Evers once said of his friend, “There is nobody less likely to dance than Raoul, but apparently he did.” In fact, he did it in earnest, professionally, right before turning to sculpture. Soon after the 17-year-old Armenian refugee began his studies at the Art Institute of Chicago, a pretty Italian girl named Maria coaxed him into joining her on the vaudeville stage. She even convinced him to change his name to Raoul, so they could be billed as “Raoul & Maria, the Tango Sensation.” Publicity photos from the time picture a young man with matinee idol good looks, wearing a Spanish hat set at a rakish angle. Though it might seem a long way from this “tango sensation” to the sculptor on Maverick Road, the fact is that Hague never stopped dancing; he just transformed the dance into direct carving. His sculptures materialize the movement of the body in space, over time. Two bodies—man and tree—work on one another. Their interaction might be violent at one moment, and tender in the next. From the outside, it might look more like a fight than a dance. But for Hague, it was a way of life, and he was thoroughly absorbed in this dance for over 50 years.

Raoul Hague and Robert Frank were friends. You can see how much they enjoyed each others’ company by looking at their faces in the photographs of them together taken by a third friend, the photographer Brian Graham. Hague and Frank had much in common. Both were expatriates and bohemians, and both were fiercely independent of the institutional New York art world and similarly allergic to its cant and puffery. It’s why Hague moved up to the cabin on Maverick Road to work, and why Frank escapes to Mabou.

But there is another reason, a better one, to look at the works of these two artists together. Frank’s photographs of Hague’s sculptures have the effect of reanimating them, putting them back in motion to correspond to the way we see the sculptures. Many people over the years have remarked on the extreme difficulty of photographing Hague’s sculptures, because they exist so insistently in three dimensions. Hague carved these sculptures in the round, turning them constantly as he worked, and to see them one must move around and keep moving. Each movement of the viewer yields a new view of the work, and the effect is cumulative. Frank’s photographs work so well because they accept this limitation, and revel in the fragmentary and contingent nature of the representation. As always in Frank’s work, images are combined to add up to something much more than can occur with a single image. This is particularly appropriate in relation to Hague, who spent his entire life as a sculptor trying to make whole forms from fragments, and building a body of work that is greater than any single piece.

In 1978, Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander realized that they had both been photographing Hague’s sculptures for some time, and wanted to do something as a gesture of admiration for the sculptor and his work. The result was a limited edition portfolio produced by the Eakins Press in New York, titled The Sculptures of Raoul Hague: Photographs by Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander. Each photographer made six sets of prints that were combined into six albums. This was the most limited edition the Eakins Press ever produced, and none of the copies were offered for sale.

Photography has always had a complex relationship with sculpture. Its static, two-dimensional rendering paradoxically heightens and clarifies sculpture’s occupation of three-dimensional space. In memorializing single temporal views, photographs call attention to the kinetic push of sculpture. A viewer cannot look at photographs while he or she is moving, and can only look at sculptures by moving, so the distance between the two media never collapses entirely. The gap between image and object remains unbridgeable, and a certain charge accrues from bringing them into close proximity.

In his six images of Wallkill Walnut, 1964, Frank circles the sculpture as it sits on a rough stand in Hague’s studio, watching the way sunlight plays over it, picking out its planes and modulating its textures. The sculpture has just been completed, and Frank is not displaying it, but regarding it, with pleasure and curiosity. We imagine Hague standing off to the side, looking at Frank looking at the sculpture.

For an abstract artist, Hague had an overwhelming appetite for realistic images. He produced no drawings, but collected thousands of photographic images from books, magazines, and newspapers, and collaged them onto the walls of his studio and house: Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo, Assyrian reliefs and Arabic calligraphy, Muybridge’s camels, Christo’s umbrellas, a group of mannequin heads wearing bridal veils, and lots and lots of dancers.

In 1971, Leo Steinberg said of Hague, “I continue to feel that this fine sculptor has been unjustifiably ignored,” and in 1998, Donald Kuspit, writing in Artforum, called Hague “a major figure accorded only minor recognition.”6 You will hear it said of Hague that he turned his back on the New York art world when he moved up to Woodstock in 1943 (as some also say of his friend and next-door neighbor Philip Guston, who did the same thing 24 years later), and there is some truth in that. But what he also did was put himself in a position to devote himself wholly to the practice of his art, without the (to him) intolerable distractions of showing and promoting his work. When he did finally have his first one-man show at Egan Gallery in 1962, the then 57-year-old Hague said he was so distracted that he “couldn’t work for a week after seeing it.”

In a prescient piece published in ARTnews in 1955, Thomas B. Hess wrote: “Perhaps we are entering a period of underground art, and men like Raoul Hague … will fill catacombs near their studios with works which will be the marvels of the future.”7 And that’s more or less what’s happened, with Hague’s sculptures preserved in storage sheds near his studio. Hague cared little for the trappings of success in his lifetime, but he well knew the value of his work, so he took care to preserve it. Now others have taken care, and we are the beneficiaries.

One of the signal pleasures of spending time with Hague’s work is the way it causes us to slow down and look. It took time to make these sculptures and it takes time to see them. A glance will yield very little. The act of reanimating matter does not happen quickly and its results take time to contemplate. If this kind of time is no longer available to us, then Hague’s sculptures will eventually become ciphers, and we will have lost something critical to our survival. Hague used to say that Arshile Gorky had teased him in the 1940s about being “behind the times,” but Hague thought then that his sculptures might come through in the end, like the tortoise passing the hare. And well they might, if anyone is still around to see the finish.