The writer Carlo McCormick did an important interview with Mike Bidlo in 1985, in which these two active participants in the East Village art scene of the early 1980s discussed the successes and failures of Bidlo’s performances and installations during this time. Near the end of the interview, Bidlo is talking about the “public entertainment” aspect of his Yves Klein piece (Not Yves Klein Anthropometries, performed at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1986), and McCormick says, “Something like this quote of yours on the wall: ‘When I am alone with myself, I have not the courage to think of myself as an artist in the great and ancient sense of the term. Giotto, Titian, Rembrandt, and Goya were great painters; I am only a public entertainer who had understood his times and has exhausted as best he could the imbecility, the vanity, the cupidity of his contemporaries. Mine is a bitter confession more painful than it may appear, but it has the merit of being sincere.’” We imagine a long pause, and then Bidlo replies, “Well, to tell you the truth, Picasso said it—not me!”1

The question of plagiarism or forgery (and thus of originality and authenticity) is never far from any discussion of value in art, and the recent substitution of the term “appropriation” for the older terms has done little to clarify the basic issues. As Rosalind Krauss so deftly demonstrated in her book The Originality of the Avant-garde and Other Modernist Myths, artists have always made copies. Every good artist appropriates ideas, images, and techniques from the past, and great artists do it with abandon. But this fact has been obscured by the modern rhetoric of originality. As Krauss says, “The discourse of originality … represses and discredits the complementary discourse of the copy. Both the avant-garde and modernism depend on this repression.”2

Copying is the one area of art in which the intent of the artist actually matters. If an “American Friend” copies a painting by Picasso with the intent to sell it as a Picasso, that is forgery. But if one copies Guernica and shows it at Larry Gagosian’s gallery, or copies Demoiselles d’Avignon and a number of other Picasso paintings of women and shows them all together at Leo Castelli’s gallery, and then Gagosian and Castelli sell the paintings not as original works by the Spanish painter but under the name of their “forger,” Mike Bidlo, that is something else entirely.3 In this case, the intent is not to deceive but to enlighten.

So, what are we looking at when we look at a Mike Bidlo copy of a painting by Picasso, or Matisse, or Cézanne, Léger, De Chirico, Kandinsky, Man Ray, Morandi, Pollock, De Kooning, Yves Klein, Franz Kline, Lichtenstein, or Warhol? A study? A facsimile? A later performance of an original score? A kind of impersonation or visual ventriloquism? An homage? A pastiche? An enchantment?

We might notice that Bidlo’s copy of a Franz Kline painting has a very different relation to its original than does a copy of a Lichtenstein painting, or one by Yves Klein. We might try to determine whether Bidlo’s Not De Chirico is closer in its effect to early or late De Chirico. We’ll recognize that the distance between Bidlo’s recreations and the originals is drastically reduced when both are seen, as they most often are, in reproduction, in books. And we can’t help but track the copyist’s relative affinity with each artist he engages: his preference for Picasso over Matisse, Pollock over Kline, Lichtenstein over Warhol. It might also occur to us as we look at these works that we usually judge quality in art by measuring difference and with these works we do it by measuring likeness and that this is a significant turn.

Looking back over many years of Bidlo’s investigations in this area, the obsessive intensity of his quest begins to emerge, with a kind of innocent adherence that seems wholly incongruous with the public life of the works. Only someone who considers art to be the most important thing in the world would spend so much time debunking its myths and testing its limits. Tradition must go to extraordinary lengths to operate today, to carry it across. “Appropriation” gets people excited because it is a crime against property; it threatens our sense of propriety. Out of imposture, Bidlo has forged a distinctive practice. “Ultimately,” he’s said, “my goal is to confront and challenge the viewer to accept these works as mine.”4

They always say that time changes things,

but you actually have to change them yourself.

—Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975)5

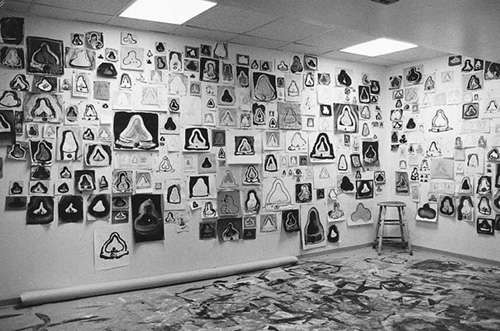

From 1996 to 1998, Bidlo made some 3,000 drawings of Duchamp’s readymade urinal. These are no more “copies” of Duchamp’s Fountain than are Ellsworth Kelly’s drawings of plants and flowers “copies” of their subjects. Each one of “The Fountain Drawings” is unique, and the range of articulation across them is astonishing, from a well-rendered pencil sketch to an abstract smear on a page from a phonebook, from schematic drawings to cartoons, from ink blots to fine lines to gouache. There are Rorschachs, Buddhas, animations, organic abstractions, rustic caves, and refined lingam/yonis. One of my favorites imposes a thickly painted outline of the urinal onto a page from an art history text discussing the symbolism of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

One is reminded that after Alfred Stieglitz photographed Fountain at “291” in April 1917, Carl Van Vechten wrote to Gertrude Stein in Paris telling her that Stieglitz’s photographs of the urinal “make it look like anything from a Madonna to a Buddha.”6

“The Fountain Drawings” have been a veritable fountain of youth for Bidlo, a principal source and point of origin for a new beginning. It’s as if Bidlo’s originality had been voluntarily held in balance with the copy for all these years, and was now exploding out of him like a, well, like a fountain.

“The Fountain Drawings,” East Village cellar studio view (1997) by Mike Bidlo; courtesy of the artist

Before beginning the drawings of the “Fountain” series, Bidlo spent five years fashioning careful replicas of Fountain (in ceramics), of the Bottle Rack in meticulous detail, and of glass ampules containing not Paris air but Bidlo’s breath (a sort of miniature monument to inspiration. Duchamp: “I am a respirateur—a breather. I enjoy that tremendously”).7 In the fall of 1996, Bidlo also mounted an homage installation of relics—the Bicycle Wheel, Fountain, the Bottle Rack, as well as copies of Nude Descending a Staircase and T um’—in his little storefront in the East Village. He christened it “Saint Duchamp,” intending the French pun on “sans Duchamp.”

There are many who think we have moved (or are moving) out of the age of art into a new age of the image. If this is true, Bidlo’s investigations may be especially appropriate to our present condition. He returns to making handmade images of a readymade symbol (Duchamp said he resorted to the readymade “to cut my hands off”) in order to show that originality can be as rampant and seemingly endless as the copy. We recall here also Duchamp’s invention of the “infra-mince” (infra-thin) to measure the subtlest differences between supposedly identical things (like twins, or clones). Duchamp was investigating this at about the same time that Walter Benjamin was writing “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” If only the two could have gotten together in 1936 and compared notes!

Bidlo himself has said that, in “The Fountain Drawings,” he brings “a symbolist aspect to the piece” that Duchamp didn’t wish to pursue. “Maybe he saw them [the symbolic references] but was too much of a rationalist to see any merit in pursuing this kind of symbolism … like he thought it was outside of his formalist concerns. Or maybe he wanted the viewer to discover it for himself, like a hidden message.”8

Bidlo’s attraction to Duchamp makes perfect sense, of course, for it was Duchamp who pushed the investigation of the reciprocity between reproducibility and originality to a new level. Judged as an influence on later art and discourse, Duchamp’s work can only be seen as wildly successful. But as an attempt to change the way art operates in the world, it was a failure, as all art historically is, for that change must be made anew by each generation.

In a short entry on Mike Bidlo for Artforum’s “Best of 1998” issue, Wayne Koestenbaum called “The Fountain Drawings” “the diary of a perverse quest,” and asked the substantive question “Why move on from illuminations that haven’t yet been understood?”9 This is as concise and elegant a statement of the rationale for Bidlo’s way of working as we are ever likely to find. The truth is that Bidlo is engaged in an inquiry that will never end. “Copying is the instinctive means of learning,” he has said. “For me at least, recreating a work in any form becomes revelatory.”10 And one good revelation deserves another, and another, and another, and …

The Yearling (1992) by Donald Lipski; courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York City