Hosephat and the Wooden Shoes

ROBERT DUNCAN AND DÉLIRE

I shall be drawn thru in music

I shall be drawn thru in pain

I shall be drawn thru in delirium.

—Robert Duncan, “A Letter to Jack Johnson” (1942)

The people about him said he had been for some time delirious; but when I saw him he had his understanding as well as ever I knew.

—Jonathan Swift, “The Death of Partridge” (1706)

The Duncan books that are most present for me now are his last ones, the two volumes of Ground Work: Before the War (1984) and In the Dark (1987). I experienced these poems first in hearing Duncan read them, and for me it is only now that I can read them without hearing Duncan’s reading voice in my ear. Now they come to me straightaway, without pause or mediation. They are so much in the furrow that their music seems to me inevitable.

The Ground Work poems are vatic, and their urgent truths and prophetic futures are becoming more and more insistent as time passes. But now I want to address that part of Duncan’s life and work that was “out of the furrow.” It goes under the name délire. It was there at the beginning and came around in force at the end of Duncan’s life.

I have been guided in my inquiries into délire by the work of Jean-Jacques Lecercle, whose book Philosophy through the Looking Glass was published in 1985 (the same year as Duncan’s essay on Jabès, “The Delirium of Meaning”). Both Philosophy through the Looking Glass and Lecercle’s later book The Violence of Language are concerned with what Robin Blaser has called “the big gift, a Trojan Horse: the materiality of language.” Lecercle has been described as “a worldwide authority on Nonsense” (an enviable title). His books have the advantage over many others of this period in not reading as if they are translated from the French. Though drawing mainly from French theory, Lecercle himself writes in a remarkably lucid English prose.

In Philosophy through the Looking Glass, Lecercle sets out to track the tradition of délire, or “reflexive delirium.” He writes:

Délire as I shall now use the word is a form of discourse which questions our most common conceptions of language (whether expressed by linguists or by philosophers), where the old philosophical question of the emergence of sense out of nonsense receives a new formulation, where the material side of language, its origin in the human body and desire, are no longer eclipsed by its abstract aspect (as an instrument of communication or expression). Language, nonsense, desire: délire accounts for the relations between these three terms.1

Lecercle’s aim is to “provide a solution to what has emerged as our main problem, the problem of abstraction, that is of the relationship between sounds as materially produced by organs of the body, and sense as the immaterial entity transmitted in human communication.”2

More than anything else, délire means “abandoning control of and mastery over language. The logophilist no longer speaks through language, he is spoken by it. This is the core of the experience of language in délire: an experience of madness in language, of possession.” Lecercle describes this possession, in délire, as “the experience of the body within language, of the destruction and painful reconstruction of the speaking subject, not through the illusory mastery of language and consciousness, but through possession by language.” And he quotes Louis Wolfson’s Le Schizo et les Langues (1970) saying, “The psychotic’s cure does not consist in becoming conscious, but in living through words the story of love.”3

Here we can’t help but recognize Duncan, as in the opening lines of The Truth and Life of Myth:

Wherever life is true to what mythologically we know life to be, it becomes full of awe, awe-full. All the events, things and beings, of our life move then with the intent of a story revealing itself. When a man’s life becomes totally so informed that every bird and leaf speaks to him and every happening has meaning, he is considered to be psychotic. The shaman and the inspired poet, who take the universe to be alive, are brothers germane of the mystic and the paranoiac. We at once seek a meaningful life and dread psychosis, “the principle of life.”4

In the four main parts of Philosophy through the Looking Glass, Lecercle traces the language of délire through literature, linguistics, philosophy, and psychoanalysis. The literature of délire is limited here to considerations of the works of Raymond Roussel, Jean Pierre Brisset, Antonin Artaud, and Louis Wolfson. In this, Lecercle remains with the texts that were assembled into a corpus of délire in the 1960s by a group of philosopher-critics including Michel Foucault, Julia Kristeva, and Gilles Deleuze. But many of Lecercle’s characterizations of the language of délire can be applied outside of that context, certainly to Duncan. In writing about Roussel and Brisset, Lecercle says:

Language in Roussel was a source of anxiety, a danger to the sanity of the writer: in Brisset, it is the only source of truth and the scribe must lose himself in it, let it regain its mastery, without which no remembrance of origins is possible. On the one hand a poet, for ever fighting for a mastery over language which constantly threatens to evade him: on the other hand a prophet, joyfully and gratefully possessed by language.”5

Duncan would of course never have divided things that way, or if he had, he might very well have reversed them.

In his chapter on the linguistics of délire, Lecercle outlines the thesis of the centrality of language, mainly coming out of Lacan, but going back to Freud, and forward to Luce Irigaray and the linguist Judith Milner. The chapter on philosophy deals primarily with Deleuze, in Logique du Sens, where “proliferation is always a threat to order.” Lecercle writes, “If délire is concerned with the relationship between language and the human body, sense as Deleuze analyses it dwells on the frontier between them; indeed it is the frontier.”6

Lecercle’s chapter on the psychoanalysis of délire focuses on the famous case of Schreber, examining both Freud’s and Lacan’s readings of it. Lecercle closes this chapter with a contradiction: “délire as a form of speech has two fundamental roles—it testifies to a disruption of discourse, and it is an attempt at reconstruction.” His concluding chapter is titled “Beyond Délire.” It begins with George Herbert and lands squarely on Deleuze and Guattari:

The first comment one can make about délire is that the truth about it cannot be grasped from the outside: it requires a degree of involvement and renunciation on the part of the philosopher. He must abandon his normal processes of thought, proceed by paradox (Deleuze and Guattari talk of the “bright black truth” of délire—Anti-Oedipus, p. 9), he must become delirious.

Lecercle ends by saying that Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus “give the first positive account of délire as constitutive of language.”7

I’ve described elsewhere the delirious effects of Duncan’s speech on the students in the Poetics Program in San Francisco, how we experienced his lectures as a kind of delirium that we often needed to protect ourselves from in order not to become sick with it.8 (The root of the word délire is the verb meaning “to teach,” literally, “to lead someone on his way.”) And Duncan spoke and wrote often of himself as being possessed by language, a victim of his own logorrhea. Lecercle writes that “délire is first characterized by logorrhea, an unceasing flow of words, indicating that communication is no longer possible.”9 One of Duncan’s running jokes was that when he finally did become senile, how would anyone be able to tell?

In the summer of 1986, after Duncan had been on dialysis for some time, he suddenly became delirious and was hospitalized. This is a notebook entry of mine from July 21, 1986:

I’ve just come from a visit with Robert Duncan at Seton Medical Center in Daly City. Susan Thackrey was there when I arrived. Joanna McClure and Jess had just left. Robert was asleep, so Susan and I spoke in the hallway for awhile. We were told that Duncan had had a difficult night and needed to rest. After some time passed a nurse came and woke him to take his temperature and blood pressure. When he awoke he looked up at me and beckoned us in. Susan and I went in and sat down next to his bed and he began to speak. He said he’d been travelling in Russia, land of “stalwart young men on trains.” He picked up a cup from his table, examined it, and said “This is certainly an American cup.” When Susan picked up a cellophane-wrapped package of candies on his bedside table and asked if they were his, he replied, “What would a jackass have on his table?”

His room was situated next door to the nursing station, so their conversation could be heard through the door. Occasionally Duncan stopped and listened intently to the voices. Once after listening for awhile, he muttered “Hypocrites!” and turned back to us. The fifth issue of my literary journal ACTS had just appeared and when Susan held it up, Duncan said that Kenneth Rexroth was behind that magazine. When I asked at one point if he was going to eat his “orange-flavored dessert,” he thought I wanted it and said, “Well, I’ll have to revise my high opinion of your intelligence if you like that. I’ll have to revise it to something more agricultural.”

Once Susan and I became accustomed to Duncan’s state, we talked and laughed as we always had, as if it all made sense. And it did, but certainly not in the way it had before. Duncan’s mannerisms, tone of voice, and gestures were unchanged, but what he said was transposed to another world. He called this world Russia, “behind the Curtain.” And he spoke of being there “before the War.” When Susan remarked that I looked very Russian, Duncan was pleased.

When I took out my brown National notebook and laid it on my lap, he picked it up, looked it over carefully, and said, “I see you’ve brought your wooden shoes.” From this point on, he always referred to my notebook in this way: “Don’t forget to bring your wooden shoes tomorrow.”

We laughed a lot. The asparagus on Duncan’s plate was cause for great hilarity, as was the frozen orange-flavored dessert. Sitting there with his hair twisted into a flame that stood straight up on top of his head, crossed eyes wild, Duncan looked quite mad. When he suddenly turned to me and asked, “Who is Hosephat?” Susan and I collapsed into uncontrollable laughter.

After leaving Duncan at the hospital, I returned home and wrote for awhile. I tried to sleep but couldn’t. Finally, at 4 a.m., I fell asleep at my desk. At 6 a.m., I awoke to see my wife, Sterrett, over me, eyes wide. “Your father is dead,” she said. I took the phone and listened to my sister tell the story. They had been awake all night, giving my father liquid morphine. He was delirious with pain, and nothing would relieve it. He moaned in agony and couldn’t speak. Finally he stopped moaning.

I got up and made arrangements to fly home to Kansas. My mind was cloudy from lack of sleep, so I laid down and slept from 11:30 to 1:30. Again Gret’s face was over me with the telephone. “It’s Jess. Duncan has refused dialysis. He says he wants to die.” Jess told me he’d been with Robert all morning in the hospital. When Dr. Conner came in to suggest that Robert have the hemodialysis that day instead of waiting until the next day, Robert said no, he would not have dialysis that day, or any other day. He would not have it at all. Jess and Susan tried to reason with him, to convince him that the doctors were trying to help him, but Duncan would have none of it. He said the doctors were “hypocrites,” and he was through with them. Later Susan, Duncan McNaughton, and Diane DiPrima spoke with Duncan and tried to reason with him. Susan tried several times to pin Robert down and make sure that he knew the consequences of his refusal of dialysis, that he would die without it. Duncan indicated that he knew this.

Later, a hospital-appointed psychiatrist came to evaluate Duncan’s condition. Susan asked to speak with Duncan before the psychiatrist. She then spoke very directly to Duncan. She told him that if he wanted to retain any control over his situation, he must convince the psychiatrist that he was sane. If he did not do this, none of his friends could help him. He would be committed to the psychiatric ward where he would most likely be given dialysis and psychiatric medication against his will. Duncan replied that these matters, the things of this world, were no longer of any concern to him. He was in another world now. He was “in the Dark.” He couldn’t come back to act on this world. “I’m caught in the Mousetrap,” he said. He looked on what was to come as the Keatsian trials—part of the process, the vale of soul-making. He also spoke of wanting out, of not wanting to reincarnate. “I don’t want to come back on the Baby-Rama,” he said.

Duncan’s delirium turned out to be iatrogenic. In the language of allopathy, it was a “side effect” of the dialysis, a chemical deficiency in the blood. Once the doctors figured that out, they righted the imbalance and the delirium immediately disappeared. Duncan lived for another two years and died on February 3, 1988, at the age of 69.

I was fortunate to have gone into Duncan’s delirium with Susan Thackrey, a practicing psychotherapist as well as poet, student in the Poetics Program, and one of Duncan’s dearest friends. She led me into the delirium. I do remember being afraid at one point that we might not be able to come back out of the delirium, we were so much inside it. And Duncan was even then crossing back and forth from this world to the next, practicing for death.

At the same time, Duncan’s delirium had many of the characteristics outlined by Lecercle. “Délire,” Lecercle writes, “is not merely an abnormal form of discourse: it is also a metalinguistic activity.”10 Many of Duncan’s pronouncements in delirium were about the delirium and the language of délire. He may have been out of the furrow, but he was still very much in the field.

His comment about having to revise his opinion of me to something more “agricultural” recalls the derivation of the word delirium, from the Latin meaning “out of the furrow,” as in ploughing the field, that ground work. In Logique du Sens, Deleuze remarks that “common sense is agricultural; it cannot be separated from the problem of enclosures….”11

This comment about my intelligence being agricultural also referred to my original absorption into the Duncan/Jess household as their gardener. Duncan hired me to bring the garden back. It had been “let go.” And off the garden was the basement, where Duncan set me up with his mimeograph machine and enough paper to print the first issues of my literary journal ACTS. Some of the best discussions I had with Duncan during that time occurred while we were both down on our knees, sifting through the soil to rid it of the corms with which the incredibly rampant Oxalis plant had colonized the garden.

Duncan’s sudden question in the hospital, “Who is Hosephat?” put Susan and me on the floor laughing because of our experience of reading the Iliad in Greek with Duncan over seven years’ time.12  is an oft-repeated Homeric beginning, meaning “So he spoke”—

is an oft-repeated Homeric beginning, meaning “So he spoke”— the “adverb of manner,” so or thus, and

the “adverb of manner,” so or thus, and  or

or  is the aorist of

is the aorist of  to speak. The latter shares with

to speak. The latter shares with  the common sense of “bringing to light, making known.” In asking “Who is Hosephat?” Duncan was asking “Who is the one who is speaking thusly?” or really, “Who is the one who is delirious?” The question blasted us out of the delirium and we exploded in laughter.13 Back of the question “Who is Hosephat?” is also David Melnick’s perverse, hilarious homophonic translation of the Iliad, Men in Aïda, written in some great measure for Duncan’s amusement. Duncan was Men in Aïda’s ideal reader.

the common sense of “bringing to light, making known.” In asking “Who is Hosephat?” Duncan was asking “Who is the one who is speaking thusly?” or really, “Who is the one who is delirious?” The question blasted us out of the delirium and we exploded in laughter.13 Back of the question “Who is Hosephat?” is also David Melnick’s perverse, hilarious homophonic translation of the Iliad, Men in Aïda, written in some great measure for Duncan’s amusement. Duncan was Men in Aïda’s ideal reader.

Duncan’s “stalwart young men on trains” in Russia recalls Schreber’s “fleeting-improvised men,” when he was convinced that everybody was dead and that he saw around him only pale images of men. Duncan reversed this, making them “stalwart.” His time in Russia was also a glimpse into the world “Before the War” of Ground Work I.

As for Duncan’s referring to my notebook as my “wooden shoes,” I’m still puzzling over that. At one point it seemed he was saying “woden shoes” (shoes of Woden). Woden, the one-eyed patriarch (he gave up one of his eyes for a drink from Mimir’s well of knowledge), was the god of war, yes, but also of poetry and magic. On his shoulders (seated on his throne in Valhalla) perched his two ravens, Hugin (Thought) and Munin (Memory), whispering in his ear. At his feet lay his two wolves, Geri and Freki, to whom Woden gave all the food that was set before him, because he had no need of food. At the time Duncan said this he was also making fun of the hospital food and was soon to refuse all food.

I also know that “wood” once meant “violently insane,” related to the Gaelic “gwyld,” whence comes our “wild,” meaning “of the forest.” And the paper on which I wrote was of course made of wood. There is also this exchange from Ella Young’s recounting of the Fionn legends and the Celtic bard Finnegas (in her Tangle-Coated Horse) that Jess uses in his “Translation #3”: “‘What help is there in words?’ said Finnegas. ‘You could not teach me how to snare the Salmon: I could not teach you more woodcraft than you know already.’ ‘You could teach me poetry,’ said Fionn.”14

I thought of this wooden shoes business recently when reading Edmund White’s biography of Jean Genet, where White describes Genet’s life as a child ward of the state: “Public Welfare would provide the children with a uniform and wooden shoes, or sabots….” And he quotes Genet from an interview recalling those days: “There were no proper shoes set aside for us; we wore wooden shoes every day, even Sunday.”15 So wooden shoes were orphan shoes, for children like Duncan.16 The traditional Scottish ballad “A Lyke-wake Dirge” reflects the belief that if you give shoes to a poor man when you are alive, an old man will meet you when you die with those very shoes, to protect your feet from the rough path ahead:

If ever thou gavest hosen and shoon,

Every night and alle,

Sit thee down and put them on,

And Christe receive thye saule.

My French dictionary tells me that sabot can mean either wooden shoes (the first act of sabotage was the clattering of wooden shoes to disrupt work, and later, a clog thrown into the works) or horses’ hooves, and the horse brings me back to Blaser’s “the big gift, a Trojan Horse: the materiality of language.”17

For Duncan, in délire, was letting go. Letting go of language, of writing, of Logos (reason), of “So he spoke.” He looked forward to this letting go again and again in his writing. In “Notes on Poetics Regarding Olson’s Maximus,” he refers to “the proposition of letting go, back to the visceral process.” And of Finnegans Wake he wrote, “Here meanings are being churned up, digested back into the original chaos of noises, decomposed.”18

But it was not just language (in Duncan, it was never “just language”) being let go. And it was not only Duncan’s “I,” the one Blaser has described as that sometimes “awfully autocratic I.” Not only the materiality of language, but materiality itself was being let go in Duncan’s practicing for death.

At the end of “The Self in Postmodern Poetry,” Duncan writes:

The Self, with a capital S, this Atman, Breath, Brahma, that moves in the word to sound I so love I also would undo the idea of, let it go. The theme increases in recent years, and back of it hovers the dissolution of the physical chemical universe which I take to be the very spiritual ground and body of our being. Something more than Death or Inertia comes as a lure in this “Letting go.” Here again it comes into the poem as it appeared as a command in dream: “Let it go. Let it go. Grief’s its proper mode.” This whole grand idea of Self—a sublime Undoing. In the coda of the Dante Etudes in Ground Work: Volume I such a rapturous prayer for dissolution appears:

AND A WISDOM AS SUCH

And a wisdom as such, a loosening

of energies and every gain! For good.

A rushing-in place of “God”, if it be!

Open out like a rose

that can no longer keep its center closed

but, practicing for Death, lets go,

let’s go, littering the ground

with petals of its rime,

“and spreads abroad the last perfume

which has been generated within”—

sweet warning the heart,

the rose hip, knows

of how soon the rapturous outpouring

speech of self into the silence of the mind

comes home, and, even the core

dispersed, in darkness of the ground

is gone

out from me, the very last of me,

till I am rid of every rind and seed

into that sweetness,

that final giving over, letting go,

that scattering of every nobleness …

“the seed of blessedness draws near despatcht

by God into the welling soul.”19

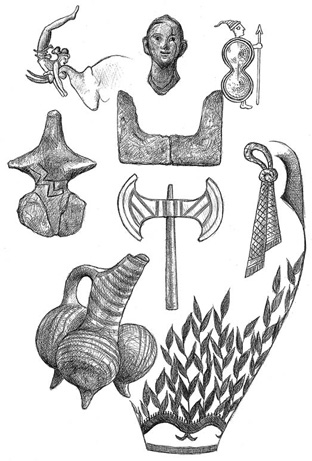

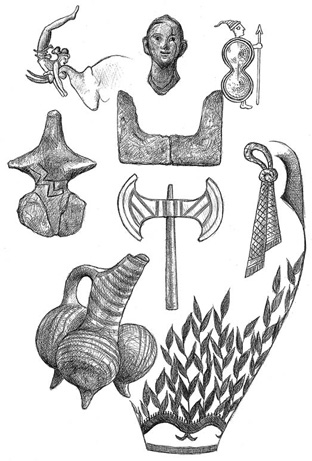

Heraklion Museum, Crete (1984) by Sterrett Smith; courtesy of the artist

is an oft-repeated Homeric beginning, meaning “So he spoke”—

is an oft-repeated Homeric beginning, meaning “So he spoke”— the “adverb of manner,” so or thus, and

the “adverb of manner,” so or thus, and  or

or  is the aorist of

is the aorist of  to speak. The latter shares with

to speak. The latter shares with  the common sense of “bringing to light, making known.” In asking “Who is Hosephat?” Duncan was asking “Who is the one who is speaking thusly?” or really, “Who is the one who is delirious?” The question blasted us out of the delirium and we exploded in laughter.13 Back of the question “Who is Hosephat?” is also David Melnick’s perverse, hilarious homophonic translation of the Iliad, Men in Aïda, written in some great measure for Duncan’s amusement. Duncan was Men in Aïda’s ideal reader.

the common sense of “bringing to light, making known.” In asking “Who is Hosephat?” Duncan was asking “Who is the one who is speaking thusly?” or really, “Who is the one who is delirious?” The question blasted us out of the delirium and we exploded in laughter.13 Back of the question “Who is Hosephat?” is also David Melnick’s perverse, hilarious homophonic translation of the Iliad, Men in Aïda, written in some great measure for Duncan’s amusement. Duncan was Men in Aïda’s ideal reader.