Under the Roman Empire the title of curator (“caretaker”) was given to officials in charge of various departments of public works: sanitation, transportation, policing. The curatores annonae were in charge of the public supplies of oil and corn. The curatores regionum were responsible for maintaining order in the 14 regions of Rome. And the curatores aquarum took care of the aqueducts. In the Middle Ages, the role of the curator shifted to the ecclesiastical, as clergy having a spiritual cure or charge. So one could say that the split within curating—between the management and control of public works (law) and the cure of souls (faith)—was there from the beginning. Curators have always been a curious mixture of bureaucrat and priest.

That smooth-faced gentleman, tickling Commodity,

Commodity, the bias of the world—

—Shakespeare, King John1

For better or worse, curators of contemporary art have become, especially in the last ten or fifteen years, the principal representatives of some of our most persistent questions and confusions about the social role of art. Is art a force for change and renewal, or is it a commodity, for advantage or convenience? Is art a radical activity, undermining social conventions, or is it a diverting entertainment for the wealthy? Are artists the antennae of the human race, or are they spoiled children with delusions of grandeur? (In Roman law, a curator could also be the appointed caretaker or guardian of a minor or lunatic.) Are art exhibitions “spiritual undertakings with the power to conjure alternative ways of organizing society,”2 or vehicles for cultural tourism and nationalistic propaganda?

These splits, which reflect larger tears in the social fabric, certainly in the United States, complicate the changing role of curators of contemporary art, because curators mediate between art and its publics, and are often forced to take “a curving and indirect course” between them. Teaching for five years (2001–5) at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, I observed young curators confronting the practical demands and limitations of their profession armed with a vision of possibility and an image of the curator as a free agent, capable of almost anything. Where did this image come from?

When Harald Szeemann and Walter Hopps died in February and March 2005, at age 72 and 71, respectively, it was impossible not to see this as the end of an era. They were two of the principal architects of the present approach to curating contemporary art, working over 50 years to transform the practice. When young curators consider what’s possible, they are imagining (whether they know it or not) some version of Szeemann and Hopps. The trouble with taking these two as models of curatorial possibility is that both of them were sui generis: renegades who managed, through sheer force of will, extraordinary ability, brilliance, luck, and hard work, to make themselves indispensable, and thereby intermittently palatable, to the conservative institutions of the art world.

Each came to these institutions early. When Szeemann was named head of the Kunsthalle Bern in 1961, at age 28, he was the youngest ever to have been appointed to such a position in Europe, and when Hopps was made director of the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum) in 1964, at age 31, he was then the youngest art museum director in the United States. By that time, Hopps (who never earned a college degree) had already mounted a show of paintings by Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Richard Diebenkorn, Jay DeFeo, and many others on a merry-go-round in an amusement park on the Santa Monica Pier (with his first wife, Shirley Hopps, when he was 22); started and run two galleries (Syndell Studios and the seminal Ferus Gallery, with Ed Kienholz); and curated the first museum shows of Frank Stella’s paintings and Joseph Cornell’s boxes, the first U.S. retrospective of Kurt Schwitters, the first museum exhibition of Pop Art, and the first solo museum exhibition of Marcel Duchamp, in Pasadena in 1963. And that was just the beginning. Near the end of his life, Hopps estimated that he’d organized 250 exhibitions in his 50-year career.

Szeemann’s early curatorial activities were no less prodigious. He made his first exhibition, Painters Poets/Poets Painters, a tribute to Hugo Ball, in 1957, at age 24. When he became the director of the Kunsthalle in Bern four years later, he completely transformed that institution, mounting nearly 12 exhibitions a year, culminating in the landmark show Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, in 1969, exhibiting works by 70 artists, including Joseph Beuys, Richard Serra, Eva Hesse, Lawrence Weiner, Richard Long, and Bruce Nauman, among many others.

While producing critically acclaimed and historically important exhibitions, both Hopps and Szeemann quickly came into conflict with their respective institutions. After four years at the Pasadena Art Museum, Hopps was asked to resign. He was named director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1970, then fired two years later. For his part, stunned by the negative reaction to When Attitudes Become Form from the Kunsthalle Bern, Harald Szeemann quit his job, becoming the first “independent curator.” He set up the Agency for Spiritual Guestwork and cofounded the International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art (IKT) in 1969, curated Happenings & Fluxus at the Kunstverein in Cologne in 1970, and became the first artistic director of Documenta in 1972, reconceiving it as a 100-day event. Szeemann and Hopps hadn’t yet turned 40, and their best shows were all ahead of them. For Szeemann, these included Junggesellenmaschinen—Les Machines célibataires (“Bachelor Machines”) in 1975–77, Monte Veritá (1978, 1983, 1987), the first Aperto at the Venice Biennale (with Achille Bonito Oliva, 1980), Der Hang Zum Gesamtkunstwerk, Europaïsche Utopien seit 1800 (The quest for the total work of art) in 1983–84, Visionary Switzerland in 1991, the Joseph Beuys retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 1993, Austria in a Lacework of Roses in 1996, and the Venice Biennale in 1999 and 2001. For Hopps, yet to come were exhibitions of Diane Arbus in the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1972, the Robert Rauschenberg midcareer survey in 1976, retrospectives at the Menil Collection of Yves Klein, John Chamberlain, Andy Warhol, and Max Ernst, and exhibitions of Jay DeFeo (1990), Ed Kienholz (1996 at the Whitney), Rauschenberg again (1998), and James Rosenquist (2003 at the Guggenheim). Both Szeemann and Hopps had exhibitions open when they died—Szeemann’s Visionary Belgium, for the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, and Hopps’s George Herms retrospective at the Santa Monica Museum—and both had plans for many more exhibitions in the future.

Szeemann and Hopps were the Cosmas and Damian (or the Beuys and Duchamp) of contemporary curatorial practice. Rather than accepting things as they found them, they changed the way things were done. But finally, they will be remembered for only one thing: the quality of the exhibitions they made; for that is what curators do, after all. Szeemann often said he preferred the simple title of Ausstellungsmacher (exhibition-maker), but he acknowledged at the same time how many different functions this one job comprised: “administrator, amateur, author of introductions, librarian, manager and accountant, animator, conservator, financier, and diplomat.”3 I have heard curators characterized at different times as:

Administrators

Advocates

Auteurs

Bricoleurs (Hopps’s last show, the Herms retrospective, was titled “The Bricoleur of Broken Dreams …One More Once”)

Brokers

Bureaucrats

Cartographers (Ivo Mesquita)

Catalysts (Hans Ulrich Obrist)

Collaborators

Cultural impresarios

Cultural nomads

Diplomats (when Bill Lieberman, who held top curatorial posts at both the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, died in May 2005, ARTnews described him as “the consummate art diplomat”)

And that’s just the beginning of the alphabet. When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked Walter Hopps to name important predecessors, the first one he came up with was Willem Mengelberg, the conductor of the New York Philharmonic, “for his unrelenting rigor.” “Fine curating of an artist’s work,” he continued,

that is, presenting it in an exhibition—requires as broad and sensitive an understanding of an artist’s work that a curator can possibly muster. This knowledge needs to go well beyond what is actually put in the exhibition…. To me, a body of work by a given artist has an inherent kind of score that you try to relate to or understand. It puts you in a certain psychological state. I always tried to get as peaceful and calm as possible.4

But around this calm and peaceful center raged the “controlled chaos” of exhibition-making. Hopps’s real skills included an encyclopedic visual memory, the ability to place artworks on the wall and in a room in a way that made them sing,5 the requisite personal charm to get people to do things for him, and an extraordinary ability to look at a work of art and then account for his experience of it, and articulate this account to others in a compelling and convincing way.

It is significant, I think, that neither Szeemann nor Hopps considered himself a writer, but both recognized and valued good writing, and solicited and “curated” writers and critics as well as artists into their exhibitions and publications. Even so, many have observed that the rise of the independent curator has occurred at the expense of the independent critic. In an article published in 2005 titled “Do Art Critics Still Matter?” Mark Spiegler opined that “on the day in 1969 when Harald Szeemann went freelance by leaving the Kunsthalle Bern, the wind turned against criticism.”6 There are curators who can also write criticism, but these precious few are exceptions that prove the rule. Curators are not specialists, but for some reason many of them feel the need to use a specialized language, appropriated from philosophy or psychoanalysis, that too often obscures rather than reveals their sources and ideas. The result is not criticism, but curatorial rhetoric. Criticism involves making finer and finer distinctions among like things, while the inflationary writing of curatorial rhetoric is used to obscure fine distinctions with equivocating language. The latter’s displacement of the former has a political dimension, as we move culturally into an increasingly managed, postcritical environment.

Although Szeemann and Hopps were very different in many ways, they shared certain fundamental values: an understanding of the importance of remaining independent of institutional prejudices and arbitrary power arrangements; a keen sense of history; the willingness to continually take risks intellectually, aesthetically, and conceptually; and an inexhaustible curiosity about and respect for the way artists work.

Szeemann’s break away from the institution of the Kunsthalle was, simply put, “a rebellion aimed at having more freedom.”7 This rebellious act put him closer to the ethos of artists and writers, where authority cannot be bestowed or taken, but must be earned through the quality of one’s work. In his collaborations with artists, power relations were negotiated in practice rather than asserted as fiat. Every mature artist I know has a favorite horror story about a young, inexperienced curator trying to claim an authority they haven’t earned by manipulating a seasoned artist’s work or by designing exhibitions in which individual artists’ works are seen as secondary and subservient to the curator’s grand plan or theme. The cure for this kind of insecure hubris is experience, but also the recognition of the ultimate contingency of the curatorial process. As Dave Hickey said of both critics and curators, “Somebody has to do something before we can do anything.”8 In June 2000, after being at the pinnacle of curatorial power repeatedly for over 40 years, Harald Szeemann said, “Frankly, if you insist on power, then you keep going on in this way. But you must throw the power away after each experience, otherwise it’s not renewing. I’ve done a lot of shows, but if the next one is not an adventure, it’s not important for me and I refuse to do it.”9

When contemporary curators, following in the steps of Szeemann, break free from institutions, they sometimes lose their sense of history in the process. Whatever their shortcomings, institutions do have a sense (sometimes a surfeit) of history. And without history, “the new” becomes a trap, a sequential recapitulation of past approaches with no forward movement. It is a terrible thing to be perpetually stuck in the present, and this is a major occupational hazard for curators.

Speaking about his curating of the Seville Biennale in 2004, Szeemann said, “It’s not about presenting the best there is, but about discovering where the unpredictable path of art will go in the immanent future.” But moving the ball up the field requires a tremendous amount of legwork. “The unpredictable path of art” becomes much less so when curators rely on the Claude Rains method, rounding up the usual suspects from the same well-worn list of artists that everyone else in the world is using.

It is difficult, in retrospect, to fully appreciate the risks both Szeemann and Hopps took to change the way curators worked. One should never underestimate the value of a monthly paycheck. By giving up a secure position as director of a stable art institution and striking out on his own as an “independent curator,” Szeemann was assuring himself years of penury. There was certainly no assurance that anyone would hire him as a freelance. Anyone who’s chosen this path knows that freelance means never having to say you’re solvent. Being freelance as a writer and critic is one thing: the tools of the trade are relatively inexpensive, and one need only make a living. But making exhibitions is costly, and finding “independent” money, money without onerous strings attached to it, is especially difficult when one cannot, in good conscience, present it as an “investment opportunity.” Daniel Birnbaum points out that

all the dilemmas of corporate sponsorship and branding in contemporary art today are fully articulated in [“When Attitudes Become Form”]. Remarkably, according to Szeemann, the exhibition came about only because “people from Philip Morris and the PR firm Ruder Finn came to Bern and asked me if I would do a show of my own. They offered me money and total freedom.” Indeed, the exhibition’s catalogue seems uncanny in its prescience: “As businessmen in tune with our times, we at Philip Morris are committed to support the experimental,” writes John A. Murphy, the company’s European president, asserting that his company experimented with “new methods and materials” in a way fully comparable to the Conceptual artists in the exhibition. (And yet, showing the other side of this corporate-funding equation, it was a while before the company supported the arts in Europe again, perhaps needing time to recover from all the negative press surrounding the event.)10

So the founding act of “independent curating” was brought to you by …Philip Morris! Thirty-three years later, for the Swiss national exhibition Expo.02, Szeemann designed a pavilion covered with sheets of gold, containing a system of pneumatic tubes and a machine that destroyed money—two 100-franc notes every minute during the 159 days of the exhibition. The sponsor? The Swiss National Bank, of course.

When Walter Hopps brought the avant-garde to Southern California, he didn’t have to compete with others to secure the works of Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, or Jay DeFeo (for the merry-go-round show in 1953), because no one else wanted them. In his Hopps obituary, Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight pointed out that “just a few years after Hopps’ first visit to the [Arensbergs’] collection, the [Los Angeles] City Council decreed that Modern art was Communist propaganda and banned its public display.”11 In 50 years, we’ve progressed from banning art as communist propaganda to prosecuting artists as terrorists.12

It’s not that fast horses are rare,

but men who know enough to spot them

are few and far between.

—Han Yü13

The trait Szeemann and Hopps had most in common was their respect for and understanding of artists. They never lost sight of the fact that their principal job was to take what they found in artists’ works and do whatever it took to present it in the strongest possible way to an interested public. Sometimes this meant combining it with other work that enhanced or extended it. This was done not to show the artists anything they didn’t already know, but to show the public. As Lawrence Weiner pointed out in an interview in 1994, “Everybody that was in the Attitudes show knew all about the work of everybody else in the Attitudes show. They wouldn’t have known them personally, but they knew all the work…. Most artists on both sides of the Atlantic knew what was being done. European artists had been coming to New York and U.S. artists went over there.”14 But Attitudes brought it all together in a way that made a difference.

Both Szeemann and Hopps felt most at home with artists, sometimes literally. Carolee Schneemann described for me the scene in the Kunstverein in Cologne in 1970, when she and her collaborator in “Happenings and Fluxus” (having arrived and discovered there was no money for lodging) moved into their installations, and Szeemann thought it such a good idea to sleep on site that he brought in a cot and slept in the museum himself, to the outrage of the guards and staff. Both Szeemann and Hopps reserved their harshest criticism for the various bureaucracies that got between them and the artists. Hopps once described working for bureaucrats when he was a senior curator at the National Collection of Fine Arts as “like moving through an atmosphere of Seconal.”15 And Szeemann said in 2001 that “the annoying thing about such bureaucratic organizations at the [Venice] Biennale is that there are a lot of people running around who hate artists because they keep running around wanting to change everything.”16 Changing everything, for Szeemann, was just the point. “Artists, like curators, work on their own,” he said in 2000, “grappling with their attempt to make a world in which to survive…. We are lonely people, faced with superficial politicians, with donors, sponsors, and one must deal with all of this. I think it is here where the artist finds a way to form his own world and live his obsessions. For me, this is the real society.”17 The society of the obsessed.

Although Walter Hopps was an early commissioner for the São Paolo Biennale (1965: Barnett Newman, Frank Stella, Richard Irwin, and Larry Poons) and of the Venice Biennale (1972: Diane Arbus), Harald Szeemann practically invented the role of nomadic independent curator of huge international shows, putting his indelible stamp on Documenta and Venice and organizing the Lyon Biennale and the Gwangju Biennale in Korea in 1997, and the first Seville Biennale in 2004, as well as numerous other international surveys around the world.

So what Szeemann said about globalization and art should perhaps be taken seriously. He saw globalization as a euphemism for imperialism, and proclaimed that “globalization is the great enemy of art.” And in the Carolee Thea interview in 2000, he said, “Globalization is perfect if it brings more justice and equality to the world …but it doesn’t. Artists dream of using computer or digital means to have contact and to bring continents closer. But once you have the information, it’s up to you what to do with it. Globalization without roots is meaningless in art.”18 And globalization of the curatorial class can be a way to avoid or “transcend” the political.

Rene Dubos’s old directive to “think globally, but act locally” (first given at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972) has been upended in some recent international shows (like the fourteenth Sydney Biennale in 2004, and the first Moscow Biennial in 2005). When one thinks locally (within a primarily Euro-American cultural framework, or within a New York-London-Kassel-Venice-Basel-Los Angeles-Miami framework) but acts globally, the results are bound to be problematic, and can be disastrous. In 1979, Dubos argued for an ecologically sustainable world in which “natural and social units maintain or recapture their identity, yet interplay with each other through a rich system of communications.” At their best, the big international exhibitions do contribute to this. Okwui Enwezor’s19 Documenta 11 certainly did, and Szeemann acknowledged this when I spoke with him in Kassel in 2002. At their worst, they perpetuate the center-to-periphery hegemony and preclude real cross-cultural communication and change. Although having artists and writers move around in the world is an obvious good, real cultural exchange is something that must be nurtured. Walter Hopps said in 1996: “I really believe in—and, obviously, hope for—radical, or arbitrary, presentations, where cross-cultural and cross-temporal considerations are extreme, out of all the artifacts we have…. So just in terms of people’s priorities, conventional hierarchies begin to shift some.”20

“Art” is any human activity that aims at producing improbable situations, and it is the more artful (artistic) the less probable the situation that it produces.

—Vilém Flusser21

Harald Szeemann recognized early and long appreciated the utopian aspects of art. “The often-evoked ‘autonomy’ is just as much a fruit of subjective evaluation as the ideal society: it remains a utopia while it informs the desire to experientially visualize the unio mystica of opposites in space. Which is to say that without seeing, there is nothing visionary, but that the visionary should always determine the seeing.” And he recognized that the bureaucrat could overtake the curer of souls at any point. “Otherwise, we might just as well return to ‘hanging and placing,’ and divide the entire process ‘from the vision to the nail’ into detailed little tasks again.”22 He organized exhibitions in which the improbable could occur, and was willing to risk the impossible. In reply to a charge that the social utopianism of Joseph Beuys was never realized, Szeemann said, “The nice thing about utopias is precisely that they fail. For me failure is a poetic dimension of art.”23 Curating a show in which nothing could fail was, to Szeemann, a waste of time.

If he and Hopps could still encourage young curators in anything, I suspect it would be to take greater risks in their work. At a time when all parts of the social and political spheres (including art institutions) are increasingly managed, breaking out of this frame, asking significant questions, and setting the terms of resistance is more and more vitally important. It is important to work against the bias of the world (commodity, political expediency). For curators of contemporary art, that means finding and supporting those artists who, as Flusser writes, “have attempted, at the risk of their lives, to utter that which is unutterable, to render audible that which is ineffable, to render visible that which is hidden.”24

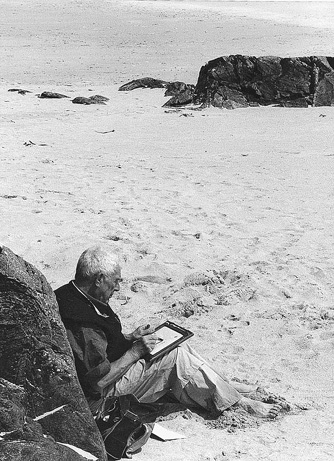

John Berger drawing on the beach in Connemara, photographed by Sarah O’Flaherty in 2004