It was not until the last quarter of the sixteenth century that missionaries penetrated the forests to the east of Peru, following down the River Ucayali and entering the Caupolican of what is now Bolivia. Except for the ill-fated expedition of Gonzalo Pizarro in 1541, organized exploration of the forests did not commence until about 15 60, and even then was undertaken spasmodically and with little worthwhile result. The conditions in the forests under the Andean foothills were utterly different from those found by the Portuguese in the low-lying and more populated region of the Atlantic coast. As the historian says:

"Easy as it was to conquer the Empire of the Incas, this was not so as regards the region east of the Andes (known commonly by the designation of 1m Montana) owing to the impenetrable forests which cover its surface. There these men of iron had to struggle against obstacles such as an almost impenetrable growth, aided at times by human beings as barbarous as Nature herself. Wide and rapid rivers, torrents capable of destroying anything which resisted them; hungry wild beasts; gigantic and poisonous reptiles; insects no less dangerous and more troublesome than the reptiles; inaccessible mountains, on whose slopes every pace carried its risk, now of going over the precipice, now of being bitten by a venomous serpent or by one of the millions of equally poisonous ants, should any plant be seized to save a fall; limitless forests, immense lagoons, swamps; torrential rains, inundations of enormous extent; constant damp, and consequently fevers which attack a man in a thousand forms; and boils painful and dangerous. To all this add an absolute lack of food. But even these circumstances were incapable of stopping men so audacious."

In one important respect the historian exaggerated. Between Cuzco and the south of Peru there were four recognized trails constructed by the Incas for military purposes. Over these, narrow and difficult though they were, the early explorers crossed the Cordilleras and descended to the forests with large trains of saddle and cargo animals. In the Caupolican province of Bolivia was a paved road ten feet wide, now long overgrown, leading from Carabaya to the Beni margin of the Plains of Mojos. On the Plains of Polopampa—as Apolobamba was called—travelling was easy, but before and beyond them the trails must have been narrow—

adequate for an Indian on foot, but extraordinarily difficult for animals. Even today the Andean trails, improved though they have been, are mostly suitable for pedestrians and agile mules only, and always with some considerable risk. Away from the trails the historian's description is not exaggerated—and the forests have changed little in 400 years.

Fired by an Indian slave's account of the riches of the Kingdom of Ambaya, Hernando Pizarro sent Pedro de Candia on the first of the forest expeditions in 1535. The next was that of Pedro Auzures, who in 1539 entered by way of Camata with considerable cavalry, came up against the Maquires in the Plains of Mojos, and lost most of his men before finally beating a retreat to the Altiplano through Cochabamba.

These efforts were followed by innumerable attempts to find the Kingdom of the Musus, and under its various appellations of Ambaya, Paititi, Emln, or Candir6, its reputed wealth continued to arouse Spanish avarice. Though the ventures failed to win fabulous riches and found only disaster, yet as a result of them missions were established and some knowledge of the geography of Peru's hinterland was gained. In 1654 Fray Tomds Chavez revived waning enthusiasm by reporting that he had been taken from Mojos in a hammock carried by Indians for a march of thirty days, followed by twelve days of canoe travel, and then twenty-one days by land, to Paititi, where the fame of his medical knowledge had reached the Emperor of the Musus. He stated that it was more thickly populated and richer in gold than Peru and all the Indies I

Similar tales of its wonders were told by a Portuguese named Pedro Bohorques in 1630, and in 1638 by an obscure person called Gil Negi "In the province of Paititi are mines of gold and silver, and great store of amber," they said. It may well be that these men were merely gratifying their vanity by claiming as personal knowledge the stories heard from the Indians.

However much romance may have coloured the tales, the fact remains that the legendary existence of a highly civilized remnant of an ancient people persisted amongst the indigenes of the continent; and these traditions can be heard today from the Indians of the remote places rarely visited by a white man. There is a remarkable similarity in the accounts, which makes it reasonable to conclude that there is a basis of truth in them.

In 1679 tne Spanish Government officially protested against the expenditure of so much money on an objective that since Pizarro's time had been attempted by seventeen expeditions, not counting those equipped by private enterprise. But it needed time and constant failure to shake the belief in the story—and meanwhile it was proving a potent factor in the exploration of the Amazon basin.

Exploration of the Madeira River by the Portuguese commenced in 1716, and of the Guapore in 1760. These joined up with the limits of

Spanish penetration, and the two nations arranged a recognized demarcation of the spheres of their respective influence. To preserve Portuguese interests and to protect a garrison from the attacks of the Araras, Pacaguaras, and other hostile tribes which swarmed in the open forests of this section, Fort Principe de Beira was built in 1783 near the confluence of the Guapor£ and Mamore Rivers, ^t still stands intact, and there is some talk of reoccupying it.

While adventurers were seeking the elusive El Dorado, more practically minded colonists of Peru were taking advantage of the abundant slave labour to operate the rich placers of Carabaya and the Altiplano, and the numerous mines that supplied the Incas with the bulk of their treasure. The immensely rich silver mountain of Potosi attracted much attention, and it is said that over one hundred million pounds sterling worth of silver formed the Royal Fifth in a single century. At Puno, on Lake Titicaca, rich silver mines were also worked. So plentiful was the metal that even the Indians possessed feeding utensils made of it, and for the shoes of horses it was found cheaper than iron. 1 Lima, capital of His Most Catholic Majesty's possessions in the New World, was fabulously wealthy by the end of the seventeenth century. I quote an eighteenth-century chronicler:

". .. But to give some idea of the wealth of that city, it may suffice to relate what Treasure the Merchants there exposed about the Year 1682, when the Duke de la Plata [Marquis de la Palata.— Ed.] made his entry as Viceroy: They caused the Streets called de la Merced, and de los Mecadores [Mercaderes.— Ed.], extending thro* two of the Quarters (along which he was to pass to the Royal Square, where the Palace is) to be paved with Ingots of Silver, that had paid the Fifth to the King: they generally weigh about 200 Marks, of eight Ounces each, are between twelve and fifteen Inches long, four or five in Breadth, and two or three in Thickness. The whole might amount to the Sum of eighty Millions of Crowns."

The immense treasures of the Incas looted in Cuzco and elsewhere, and the huge production of the mines under slave labour, created the Buccaneers of the Spanish Main and Pacific. Up to the time of the Wars of Independence, when the yoke of Spain was thrown off in the third decade of the nineteenth century, the Pacific coast was never free from semi-piratical brigs, ultimately hard-headed 'Down-Easters* masquerad-

1 But not so good! During World War II it came within the province of the editor, then a locomotive engineer in Peru, to find, for use in bearing metals, a substitute for tin, scarce because all supplies were being shipped to the U.S.A. Tests were made with silver—not as a substitute, but to see what could be done with it industrially—and the conclusion reached was that while it looked pretty when made into plates and dishes, or even in the locally popular form of chamber pots, in the field of railroad engineering it was valueless. A pity, because 'here was so much of it.— Ed.

ing as respectable raiders under letters of marque, or else making no pretence of disguising their intentions. The people of these countries had no illusions about the adventurers—they had suffered too frequently in the past from raiders such as Drake, Spilberg, Jacob the Hermit, Bartholomew Sharp and Dampier. Even our venerated Lord Anson is classified by them as nothing more than a pirate. It is interesting to note that the last Armada, or treasure fleet, left the Peruvian port of Callao in 1739 bound for the Isthmus of Panama, where treasure would be taken overland for reshipping on the Atlantic side. Anson's raid on the Pacific coast frightened the treasure ships into the Guayas River and up as far as Guayaquil, where they stayed for three years before returning to Callao with the bullion still on board.

So rich were the goldmines beyond the Cordilleras that no trouble was taken to extract the metal except in a most primitive way. Fine gold was ignored. In 1780-81, during the Indian rising led by Jose Gabriel Condorcanqui—Tupac Amaru—every Spaniard and employee east of the Andes was massacred, trails were destroyed, and every possible trace of the mines obscured. In the archives are records of the names and production of these mines, few of which have been rediscovered. Indians may know of their whereabouts, but nothing will make them talk; for in their hearts they cherish the belief that one day the Inca will return to claim his hidden treasure and his ruins, when the last vestige of Spanish rule has disappeared from the continent.

In the power of their conquerors the lot of the Indians fell from bad to worse. Under the system of Repartimientos they became slaves to be sold together with the lands where they lived. The Peonage system left them little better off, even if nominally free—they still changed hands with the land. But the Aymaras of Bolivia are of different stuff from the docile Quechuas; they are more independent, and even walk with a truculent air. It is not wise to enter without their consent some of the Aymara villages east of Lake Titicaca. Today there are 800,000 Indians in Bolivia, as against 700,000 cholos (mixed Indian and Spanish b! and the same number of whites—and the Government keeps a respectful eye on them. The Aymara of the mountains is physically rather a tine man. Even under the rags and humility of the Quechua smoulders a later.: and in spite of his apparent zeal for the Catholic Church he preserves his ancient ceremonies, conducting them in secret in the mountain fastiu The beautiful emblem of the Sun still appeals to him more than the hypocrisy of the priests and the sanguinary images in the adobe churches. Not that all the priests are hypocritical; for while many of those to be found in out-of-the-way villages are ignorant half-castes or even Indians, greedy and vice-ridden, there are also men of the highest type, especially amongst the members of the French missions and the virile, abnegating Franciscans.

With the suppression of the Jesuits in 1760 the status of the Indian

in Brazil became that of an animal, and he was hunted for the value of his labour. The importation of large numbers of Negro slaves and the acquisition of a growing army of Indians produced an extraordinary number of half-castes. It was the same on the western side of the continent. Portuguese and Spanish colonists of the best blood mixed freely with both, and the Negro in turn mixed with all the different tribes of the civilized indigenes. A very difficult social problem was created when slavery was abolished and the half-castes were placed on a level with the free population.

Brazil is by no means homogeneous except in its intense patriotism. The Negro is not regarded as an equal by the whites, and while there is freedom and a measure of camaraderie among all classes, there is below the surface as much class distinction as in any other part of the world. Indian blood is tolerated, and in some cases considered a matter for pride, just as in the U.S.A. The result is curious and interesting. Every Negro woman is so conscious of her colour bar that she spares no pains to disguise it, and when she can will mate with someone lighter in complexion than herself. This, and the selective preferences of the well-to-do classes, are breeding out the Negro, while preserving his valuable immunity to tropical diseases. More and more Europeans come to the country, marry locally, and produce—in the upper classes, at any rate—very good-looking children. Eventually there will be a fine and vigorous race free from the inherent weaknesses of inbred nations.

In the seventeenth century Brazil suffered much from lawless and independent communities of escaped Negro slaves, who were either joined by women of their own race or obtained them by raiding Indian tribes. These communities destroyed settlements and estancias, and were guilty of appalling atrocities—for under the influence of the liquor known zspinga the Negro, and particularly the Negro-Indian mestizo, becomes a wild animal.

Not many years ago, in the Leneois district of Bahia, an Englishman was unwise enough to knock down one of the Caboclos, or half-castes, for some trifling offence. The man said nothing, but went to his shack and sharpened the faca> or triangular-bladed stiletto with which insults are unhesitatingly avenged. He openly acknowledged the intention of knifing his patrao —and he did; and not even the certainty of thirty years' imprisonment could stay him. He had been struck, and that was enough 1

Although many thousands of Negroes live in both Bolivia and Peru, they are a negligible element in the population. For the most part the half-castes in these republics are the product of the European and the Indian, though it is hard to find just where black blood ceases. These half-castes are capable of even worse excesses than the full-blooded Indians, if driven by the maddening cane alcohol called chacta in Peru, kachasa in Bolivia, and pinga in Brazil.

Except in the capitals and big towns—where a cosmopolitan element produces a certain general aloofness—there is not a dwelling or village, however poor, in any one of these countries that does not dispense the unstinted hospitality I met with so often in my journeys in the interior. This is particularly the case in Brazil, where it may be counted on if the ordinary rules of courtesy be observed. No people possess less racial prejudice, or are more kindly disposed towards the stranger. But Spanish and Portuguese alike attach great importance to etiquette; and it is desirable for the foreigner to know the language. Some say these languages are easy to learn. To acquire a smattering of grammar-book talk may not be difficult, but that is not enough. Nor is it enough to reach the point of understanding either language rapidly spoken by a provincial. The necessary standard is the ability to tell a good joke, make witty remarks, and discuss philosophy and the arts. How many foreigners take the trouble to aim at that objective? The staccato and slangy pronunciation acquired by a child may be beyond the powers of an adult, but South Americans ignore the lack of this, and even shortcomings in grammar, so long as conversation is witty and intelligent. Conversation is the breath of life to them, and fifteen minutes of 'chawing the fat' with a peon about Plato or Aristotle will do more to build up mutual esteem than years of good intentions without the ability to express them. It is always a matter of surprise to Americans and Europeans to find how profound can be the conversation of even the humblest South American. 1 On the other hand, as elsewhere, the conversation of high and low can be woefully uninformed about elementary matters, as we shall see in a moment.

What annoys the people is a suggestion of superiority—and who can blame them? It is difficult to keep a straight face when an educated lady asks, as I was once asked in Bolivia, "Did the setior come from England in a canoe or on muleback?"

"No, seiiora? was my reply; "I came in a steamer carrying about a thousand people."

"Oish!" exclaimed she. "Was there no danger from currents and rapids?"

A dignitary at San Ignacio, Bolivia, hearing of the Titanic disaster, said to me out of the maturity of his river experience:

"Heavens, man! Why don't they keep near the bank? It's far safer. Those big canoes in mid-stream are always dangerous!"

A gentleman in the same village took much pride in the possession of a horrible oleo-lithograph representing a storm, a lighthouse, and a

1 1 can vouch for this being no exaggeration. The greatest mistake a foreigner can make in these countries is to insist on hustle and bustle without ever taking time out to chat with the workmen under his authority. I myself learned to converse with them because I likeJ them, and my reward was a priceless store of tales, legends and titbits of knowledge, to say nothing of the pleasure derived at the time. Besides the need to learn the colloquial language, it is worth while stressing the importance of abundant reading in that language, the ability to write it well, and—sooner or later it will be necessary—to make a speech in itl— Ed.

fantastically rough sea. lie was frequently asked if it was the Cachuela Esperanza, a well-known rapid in the Beni.

Once when I asked the postmaster in a provincial town in Peru what was the postage to England, he took the envelope, turned it upside down and sideways, scrutinized it with the most ludicrous attention, and then asked, "Where's England?" I explained to him as best I could. "Never heard of it," he said. I explained in more detail, and tried a different approach. Finally light dawned. "Oh! You mean London. England's in London, then? Why didn't you say so at first, senor?"

It sounds terribly ignorant, no doubt, but what about the society lady in London who asked if Bolivia was 'one of those horrid little Balkan states'? Another titled lady, who is now a big figure in politics, asked me in all seriousness if the people in Buenos Aires were civilized and wore clothes! Apparently she imagined that the people of one of the world's iinest cities were wild Indians—with perhaps here and there a gaucho, armed to the teeth, galloping along unpaved streets and lassoing turbulent cattle! Even the passport official of a great bank slipped up badly when in 1924 my youngest son, about to leave for Peru, applied for a passport. He enquired whether Peru might be in Chile or Brazil 1

Many parts of the interior, in all these countries, are isolated from the world by weeks of atrocious mule trails, and consequently there is no check to inbreeding and superstition. In San Ignacio, for instance, the people when ill cover up mouth, ears and nose, so that the spirit may not escape. Nearly everywhere more faith is placed in the miraculous power of wax images than in expensive medicines. There are villages where inbreeding has practically wiped out the men, but it is interesting to note that the women seem to improve in physique by it. When men from outside visit these places they have to be careful, for there is no feminine modesty!

Many foreigners consider the Indian an animal, incapable of any feelings beyond instinct. Even after four centuries of utter debasement and cruel treatment as serfs, I have always found them readily responsive to kindness, and I know them to be highly capable of education. There are Indians who have enriched themselves and become important national figures. They have started as peons, and in spite of almost insurmountable obstacles have risen to become owners of land, mines, ranches and businesses. I have met many such men in the course of my wanderings. In the countries they inhabit direct taxation is practically non-existent, indirect taxation is low, and personal liberty is unchallenged by over-legislation.

The curse of the Indian is kachasa —too often the only means of temporary escape from hopeless servitude—and he can obtain it on credit. The Indian is not the only one to drink himself into stupor; practically everyone in the interior, including the European, does so. It debases a man physically and morally, and accounts for nine-tenths of

what crime there is—which isn't very great. I am not blaming them and am certainly not going to repeat teetotal dogma. Some people fated to live under similar conditions would prefer suicide!

I hope these chapters will have made clear what I am looking for, and why. The failures, the disappointments, have been bitter, yet always there has been some progress. Had I still had Costin and Manley as companions it is possible that instead of writing an uncompleted manuscript I might now be giving to the world the story of the most stupendous discovery of modern times.

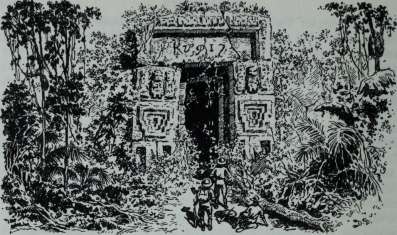

There has been disillusionment too. After the Gongugy expedition I doubted for a time the existence of the old cities, and then came the sight of remains that proved the truth of at least part of the accounts. It still remains a possibility that 'Z'—my chief objective—with its remnant of inhabitants, may turn out to be none other than the forest city found by the Bandeira of 1753. It is not on the Xingu River, or in Matto Grosso. If we ever reach it we may be delayed there for a considerable time—an unsuccessful journey will be a rapid one.

Our route will be from Dead Horse Camp, u° 43' south and 54 0 35' west, where my horse died in 1921, roughly north-east to the Xingu, visiting on the way an ancient stone tower which is the terror of the surrounding Indians, as at night it is lighted from door and windows, Beyond the Xingu we shall take to the forest to a point midway between that river and the Araguaya, and then follow the watershed north to 9 0 or io° south latitude. We shall then head for Santa Marfa do Araguaya, and from there cross by an existing trail to the Rio Tocantins at Porto Nacional or 'Pedro Afonso'. Our way will be between latitude io° 30' and 11 ° to the high ground between the States of Goyaz and BahJa, a region quite unknown and said to be infested by savages, where I expect to get some trace of the inhabited cities. The mountains there are quite high. We shall then follow the mountains between Bahia and Piauhv to the Rio Sao Francisco, striking it somewhere near Chique-Chique, and, if we are in fit condition to do so, visit the old deserted city (that of 1753) which lies at approximately n° 30' south and 42 0 30' west, thus completing the investigations and getting out at a point from which the railway will take us to Bahia City. 1

1 This is the route my father set out to follow in 1925. Experts in Brazil maintain it i< impossible to do it, and inasmuch as he never returned they may be right. The area where he believed 'Z' to lie has in recent years been regularly flown over by domestic airlines, and no trace of an ancient city has been reported. Moreover, this part of the country is not unknown— and I can hardly believe it was unexplored at the time he wrote. It is true that remains of incalculable age have been found thereabouts—on the borders of Goyaz an cs— but no city. But for over a century one has been known in the state of Piauhy, and culcd ' Uk Cidades', from its seven citadels.

I have personally investigated the bearings be gives for the 17j * <. i I tatively that it is not there.— Ed.

I have talked with a Frenchman who for some years occupied himself with tracking down the legendary silver mines, associated indirectly with the deserted city (for it was in looking for these Lost Mines of Muribeca that the 1753 Bandeirantes found it). He claims to have been all over the region I propose visiting, and states that it is populated by civilized settlers wherever there is water—that there is no real forest in that area— that no ruins can possibly exist there! He asserts that he discovered a peculiar, weather-worn formation of sandstone which from the distance looked very much like old ruins, and that this is what the Bandeirantes of 1753 actually saw, inventing the rest of their tale in the fashion of those days. When I told him of the recorded inscriptions (he had neither seen nor heard of the document left by 'Raposo') he had no answer—and in any case, various essential points did not tally with his arguments. The inscriptions on the ruins, and the 'jumping rats' (jerboas) cannot surely have been a mere invention.

Frankly, I have little confidence in the Frenchman. To have been all over such a region is hardly possible. There are sandy areas devoid of water; cliffs bar the way; even a single valley may remain hidden for centuries, for exploration has never been systematically carried out, although the lure of diamonds in this region has in the past disclosed the safe and accessible places. My impression is that there is an inner area bordered by a waterless belt that has discouraged expeditions. The Frenchman had an alcoholic breath, and I cannot consider drinkers fully reliable. I was told, too, that he had never been away for more than two or three weeks at a time—far too short a period for prolonged investigation. 1

The late British Consul at Rio, Colonel O'Sullivan Beare, a gentleman whose word I would not have dreamed of doubting, gave me as nearly as the wretchedly inaccurate maps of the region would allow the location of the ruined city to which he was taken by a Caboclo in 1913 (mentioned in Chapter I). He never crossed the Sao Francisco—his city was well east of it, twelve days' travel from Bahf a. The Sao Francisco has been associated with legends of White Indians for centuries, and it is possible that the two clothed whites seen by 'Raposo's' advance party were somewhere between the mouth of the Rio Grande and Chique-Chique. Since then, encroaching civilization may have kept them in their valley beyond the dry belt.

There are curious things to be found between the Xingu and the Araguaya, but I sometimes doubt if I can stand up to that journey. I am growing too old to pack at least forty pounds on my back for months on end, 2 and a larger expedition costs a great deal of money and runs

1 Nevertheless, from what I myself have seen, I believe the Frenchman was right. I have heard much in Bahia about this Frenchman's travels, and he really did penetrate unknown regions of the state.— Ed.

* He was fifty-seven when he wrote this in 1924.— Ed.

greater risks—besides, all the men who go must be picked men, and there is probably not more than one in a thousand who is fit for it.

If the journey is not successful my work in South America ends in failure, for I can never do any more. I must inevitably be discredited as a visionary, and branded as one who had only personal enrichment in view. Who will ever understand that I want no glory from it—no money for myself—that I am doing it unpaid in the hope that its ultimate benefit to mankind will justify the years spent in the quest? The last few years have been the most wretched and disillusioning in my life—full of anxieties, uncertainties, financial stringency, underhand dealing and outright treachery. My wife and children have been sacrificed for it, and denied many of the benefits that they would have enjoyed had I remained in the ordinary walks of life. Of our twenty-four years of married life only ten have been spent together. Apart from four years in the Great War, I have spent ten in the forests, yet my wife has never complained. On the contrary, her practical help and constant encouragement have been big factors in the successes so far gained, and if I win in the end the triumph will be largely due to her.

EPILOGUE

by Brian Fawcett

Have I named one single river? Have I claimed one single acre?

Have I kept one single nugget—(barring samples)? No, not II Because my price was paid me ten times over by my Maker.

But you wouldn't understand it. You go up and occupy.

Rudyard Kipling.

THROUGH THE VEIL

IT seemed in 1924 as though funds for the final expedition would never be forthcoming. Disappointment followed disappointment, while ever just beyond reach was the glowing image of the Great Objective—the ancient cities of Brazil. Funds were low—so low that it was a problem how the family could keep going in even a modest way—yet it was necessary to preserve an attitude of preparedness and be ready to move at a moment's notice.

Ever since his return to England late in 1921 my father's impatience to start off on his last trip was tearing at him with ever-increasing force. From reticent he became almost surly—yet there were also times when this dark mantle was laid aside, and he was again a jolly companion to us children.

We—that is, my mother, my brother, my younger sister and myself —who in 1920 set out for Jamaica, never, as we thought, to return to England, were back again in under two years. Disillusionment hastened our departure from Jamaica. The island was not, as had been hopefully expected, like Ceylon; living conditions were difficult for the white minority and educational standards were poor, and so there was another frenzy of packing and an exodus to California, which had for many years been a sort of dream Mecca. Several reasons, not the least of them the high cost of living, necessitated our departure from Los Angeles after only a year, and in September 1921 we landed at Plymouth, where a month later we went to meet my father on his arrival from Brazil.

A house was rented in Exeter for a while, and then we moved out to a dilapidated but roomy place at Stoke Canon, in the direction of Tiverton.

*75

Here we stayed till the family broke up. I was the first to go, leaving for Peru on a railway appointment. My father and brother were the next to leave. Plans had suddenly come to a successful conclusion, and off they went to New York. My mother and sister left for Madeira, where they stayed for some years before going to reside on the French Riviera, and then in Switzerland.

It was during our stay in Stoke Canon that the present book was written, and from my father's lips I heard many of the anecdotes and ideas he records. I realized too late that had I shown more interest I might have been told much more that now I would give anything to know. That's usually the way of it. At the time my enthusiasm was concentrated on locomotive engineering to the exclusion of everything else.

My father would get up at an ungodly hour of the morning to make breakfast for me before I set off on a bicycle to the engineering works in Exeter, where I was serving a grimy but interesting apprenticeship as moulder's helper in a foundry. He could turn out as good a breakfast as anybody, and his acceptance of the task with silent humility only became significant to me years later when I recalled the circumstances of that period. He did it to ensure more rest for my mother, and because he would not consider my doing it for myself.

Though the time spent in Stoke Canon must have seemed to him like a jail sentence, there were bright moments too. Cricket, ever his joy, took him and my brother—both exponents of the game up to county standards—far afield in the season, for they were much in demand.

I saw him for the last time in March of 1924, when the Liverpool train pulled out of St. David's station, Exeter, and his tall figure was lost beyond view from the carriage window. As I was whisked northwards on the first stage of the long journey to Peru I fully expected that we should meet again in a few years in South America.

"I was up in London for a week on expedition matters," he wrote in May 1924, "and it may be that things are now fixed up satisfactorily. Probably the whole business will be done in the U.S.A., and if so the results will go there too. But the Royal Geographical Society has unanimously endorsed the expedition, so at least it has scientific backing.

"Jack and I may go via New York in June, where Raleigh will join us. He is as keen as mustard. It will be a comforting feeling that we are all in the same continent."

But it was not yet to be. Arrangements took much longer to make, and in the meantime he and Jack 'went into training'. Rudiments of the Portuguese language and some experience with theodolite work were instilled into Jack; and they went vegetarian in preparation for what might make an otherwise hungry expedition less difficult to bear. Physically there was little training required. Jack's six feet three inches were sheer bone and muscle, and the three chief agents of bodily degeneration

J'.PILOGUR

*77

—alcohol, tobacco and loose living—were revolting to him. Jack made a cult of physical fitness, and the only domestic chores he never complained of doing were those requiring an exercise of strength.

At school it was always Jack who distinguished himself in games, in fights, and by standing up to the severe canings of the headmaster. In his scholastic work too he could excel when the subject interested him. I, three years his junior, followed him in my humble way, true member of the unimportant but not contemptible rank and file. Bullied into a stupor during my first term, it was Jack's ready fist that ultimately brought me respite—but thereafter he made me fight my own battles and only took part when the odds weighed too heavily against me.

At home it was Jack who formed and led the gang—Jack who kept a log book in which to record all the mischief that could truly be classed as anti-social. His able and willing lieutenant was Raleigh Rimell, son of a Seaton doctor. Raleigh was with us most of the time during these school years at Seaton. He was a born clown, perfect counterpart of the serious Jack, and between the two there sprang up a close friendship which led to the Adventure of 1925.

During the Great War (of 1914-18) we were too young to be drawn into the army, but not too young to get hold of a horrifying assortment of firearms, with which we made so free that the authorities honoured us by nominating a special constable to follow our trail and bring us within reach of the lawl I'm afraid we led the poor man a miserable life, and it ended up by our trailing the constable with intent to work mischief on him. The police never pounced; we continued to shoot inoffensive starlings off the roofs of the town's houses, and even made targets of the enamelled collection-plates on pillar-boxes. Raleigh was summoned on this charge and made to replace a broken plate at the cost of ten shillings. Whenever he passed that pillar-box he would polish the plate with his handkerchief and say, "This is mine, you knowl"

When we went to Jamaica, Raleigh was already there, working for the United Fruit Company on a coconut estate at Port Maria. Jack was employed as a cow hand on a big cattle ranch up in the Montego Bay area, on the other side of the island, but occasionally they met. Raleigh went to California ahead of us, but we saw nothing of him there, for when we arrived he had moved on. Jack, between intervals of doing nothing, worked as a chainman to a Riverside surveyor and as an orange picker. A clever but untutored draughtsman, he also did some art work for the Ij>s Angeles Times. The glamour of the movies bit him for a time—as it does most of the impressionable people who visit Hollywood—and he made perfunctory attempts to land extra parts under Betty Blythe and Nazimov.i, two stars whose names are no longer familiar but who at that time were at the height of their fame. He might have broken in, for he lacked none of the necessary looks, but a friend who was acting as technical director in

the making of an exotic picture that never saw the light— Omar Khayyam — warned him off before the celluloid octopus grasped him in its fatal rentacles. Actually, the nearest he ever came to the movies was when a property-man hired his cricket bat, because of its authentic appearance, for Mary Pickford to use in Little Lord Fauntleroy. Apart from the cash received, he was awarded a letter' of thanks and a signed photo from the star.

Towards the end of 1924 arrangements for financing the expedition were made, and a friend of my father's went off to New York in advance to raise the money and have the business concluded by the time he and Jack arrived there. When the two of them landed in the U.S.A. it was to find that this 'friend* had squandered in a glorious drunk lasting six weeks $1,000 of my father's and $500 of Mrs. Rimell's (which he got hold of from Raleigh's mother on the plea of a wildcat mining syndicate). Needless to say, he had not succeeded in raising a cent, and only £200 were recovered of the funds entrusted to him.

My father now set to work to raise enough for the expedition; and this he managed to accomplish in a month by arousing the interest of various scientific societies, and by the sale of newspaper rights to the North American Newspaper Alliance, which nominated him a special correspondent.

"We are going to have a thoroughly good time going out, and in Brazil until we vanish into the forests for three years or so," my father wrote me in September 1924, before leaving England. "I fancy Jack and Raleigh will enjoy it. On the expedition, no one else will be with the party, except two Brazilians up to a certain point only."

Then, towards the end of January 1925, he wrote from on board S.S. Vauban, of the Lamport and Holt Line:

"Here we are, with Raleigh, approaching Rio. Personally I find the

voyage rather tiresome, but Jack is thoroughly enjoying it They were

very hospitable and sympathetic in New York, but the position was of course difficult. However, we are now in the same continent with you and on the way to Matto Grosso, and with at least forty million people already aware of our objective.

"Given facilities at Rio in the Customs, etc., we shall leave for Matto Grosso in about a week, and Cuyaba about April 2. Thereafter we shall disappear from civilization until the end of next year. Imagine us somewhere about a thousand miles east of you, in forests so far untrodden by civilized man.

"New York tried us badly. It was extremely cold, under a foot of snow, and the winds were bitter. Jack haunted cinemas—which were on the whole very poor—and chewed masses of gum. All three of us took our meals at an Automat."

Now Raleigh speaks in a letter to me from Rio:

"On the voyage down I became acquainted with a certain girl on board, and as time went on our friendship increased till I admit it was threatening to get serious—in fact, your father and Jack were getting quite anxious, afraid I should elope or something! However, I came to my senses and realized I was supposed to be the member of an expedition, and not allowed to take a wife along. I had to drop her gently and attend to business. I sympathize with you if you get sentimental once in a while.

"Jack said to me the other day, 'I suppose after we get back you'll be married within a year?' I told him I wouldn't make any promises—but I don't intend to be a bachelor all my life, even if Jack does I . . .

"I have wished several times that you also were coming on this trip, as I believe you would help to make it even more interesting and cheerful. I am looking forward to the actual start of the expedition into the forest, and I think Jack shares the same feeling. With an objective like ours, it requires too much patience to remain long in one place. The delays in New York were almost more than we could bear. ..."

While in Rio de Janeiro they stayed at the Hotel Internacional, and did the rounds of sightseeing and sea-bathing. Jack was not greatly impressed, and wrote:

"I would not live in Rio or any other town here if I had a million a year, unless I could come for only a month or two at a time! I don't care about the place, though of course the surroundings are magnificent. Brazil seems frightfully cut off from the world somehow. I must say the people are awfully decent everywhere, and help in every way."

Expedition kit was tried out in the 'jungle' of the hotel garden and found satisfactory, and in February 1925 they set off, going first to S2o Paulo. From Corumba Jack wrote a lively account of the trip as seen through the eyes of an enthusiastic youth of twenty-one:

"We have spent a week in the train from Sao Paulo to Porto Esperanca, fifty miles down from Corumba, and are glad to get this far at last. The train journey was interesting, in spite of the sameness of the countr passed through, and as we were lent the Line Official's private car, pr was ours all the way. In this respect we were lucky, for from Rio to Slo Paulo, and from there to Rio Parana, we had the private car of the President of the railroad.

"Most of the way was through scrubby mato forest and grazing land, with a good deal of swamp near the river. Between Aquidauana and Porto Esperanca I saw some quite interesting things. In the cattle country were numerous parrots, and we saw two flocks (or whatever you call them) of young rheas about four to five feet high. There was a glimpse of a spider's web in a tree, with a spider about the size of a sparrow sitting in the middle. In the River Paraguay this morning there were small alligators, and we are going out to shoot at them.

"On account of the passports left behind in Rio we might have been

held up when we landed here this morning, but apparently there will now be no bother, and we sail for Cuyaba tomorrow on the Iguatemi, a dirty little launch about the size of a naval M.L. There will be a large crowd of passengers, and our hammocks will be slung almost touching one another.

"Mosquitoes were pretty bad from Bauru to Porto Esperanca, but last night on the Paraguay there were none at all. The food is good and wholesome here, and much more sustaining than in Rio or Sao Paulo. One eats rice, beans—big black ones—chicken, beef, and a sort of slug-slime vegetable, something like a cucumber in texture, egg-shaped and the size of a walnut. Then comes Goiabada (guava cheese), bread and cheese, and the inevitable black coffee. Macaroni is also a favourite dish. All this is consumed at one meal.

"The heat is pretty stifling here at present, but not so bad inside the hotel. We are fed-up with these semi-civilized towns, amiable though the people are, and want to get through our time at Cuyaba as quickly as possible so as to start off into the forest. When Raleigh and I are unusually fed-up we talk of what we will do when we revisit Seaton in the spring of 1927, with plenty of cash. We intend to buy motor-cycles and really enjoy a good holiday in Devon, looking up all our friends and visiting the old haunts.

"Our river trip to Cuyaba takes about eight days, and we shall probably have all our mules ready for fattening by the middle of March. We leave Cuyaba on April 2, and it will take us six weeks, or perhaps two months, to reach the spot Daddy and Felipe got to last time. To reach 'Z' will probably take another two months, and it may be that we shall enter the place on Daddy's fifty-eighth birthday (August 31).

"Aren't the reports of the expedition in the English and American papers amusing? There is a lot of exaggerated stuff in the Brazilian papers too. We are longing to start on the real journey, and finish with these towns, though the month in Cuyaba will probably pass fairly quickly. One thing I only realized today is that we have crossed Brazil and can see Bolivia from here—and the places where Daddy was doing much of his boundary delimitation work.

"We had a fine send-off from Sao Paulo by a number of English people, including members of the diplomatic and consular corps. Before we left there we visited the Butantan snake-farm, where Senhor Brasil, the founder, gave us a talk on snakes—how they strike, how much poison they eject, the various remedies, and so on. He presented us with a whole lot of serum. An attendant entered the enclosure where the snakes are kept, in beehive huts, surrounded by a moat, and with a hooked rod took out a bushmaster. He placed it on the ground, reached down, and caught it by the neck before it could do anything. Then he brought it over and showed us the fangs, which are hinged, and have

spare ones lying flat with the jaw in case the principal ones arc broken. Senhor Brasil let it bite on a glass saucer, and a whole lot of venom squirted out.

"Last night saw the end of Carnivals, and all the inhabitants were tearing up and down in front of the hotel, on the only bit of good road. They made the deuce of a row, and were all in home-made fancy dress, some costumes being quite pretty. The custom during Carnivals is to squirt scent at you—or ether, which gets in the eyes and freezes them. The heat is awful today, and we drip with sweat. They say that in Cuyaba it is cooler. This morning we were talking to a German just in Cuyaba, and he told us they have over a hundred Ford cars there now— not bad for a place two thousand miles up river 1 He also said he came down on the Iguatemi, the boat we go up on, and that the food is good, but the mosquitoes are bad. I hear that in the new park they have a couple of jaguars in captivity, so I think I'll go and see them.

"The lavatory arrangements here are very primitive. The combined W.C. and shower-room is so filthy that one must be careful where one treads; but Daddy says we must expect much worse in Cuyaba.

"We have been exceedingly lucky to get passages, and to have all our luggage put on board the Iguatemi intact. It will be terribly cramped, but no doubt interesting going up river. The country we have seen so far has a dreadful sameness about it, though not in this respect as bad as the Mississippi.

"We have decided not to bother about shaving between here and Cuyaba, and already I have two days' growth on me. Raleigh looks like a desperate villain, such as you see in Western thrillers on the movies."

February 25, 1925. "We are now nearly two days out of Corumba, and reach Cuyaba next Monday evening, if we haven't died of boredom before then! The boat is supposed to carry only twenty people, but fifty passengers are crowded on board. We travel about three miles an hour, through rather uninteresting swampy country, but today the monotony was broken by the sight of hills. We sleep on deck in hammocks, and it is quite comfortable except for the mosquitoes, bad enough up to now, but expected to get worse tonight when we enter the Sao Lourenco R The first night was so cold that I had to get up to put on two shirts, socks and trousers. The monotony is appalling, and there is no room for exercise of any sort. Cuyaba will seem like Heaven after this! . . .

"Most of the passengers are 'Turks' (which means here a citizen of any of the Balkan countries) and run small shops in Cuyaba. Their women jabber incessantly, and whenever a meal is imminent gather round like vultures. The smells on board are pretty bad. Every now and then we stop at the bank to take on wood fuel for the boiler, counting with great care every stick as it comes in overside.

*82 EPILOGUE

"At present the banks of the river are scrubby mato with in the background some rocky hills about eight hundred feet high. There are a few alligators to be seen, and everywhere along the edge of the river any amount of cranes and vultures. Owing to the congestion on board it is out of the question getting the guns out to shoot at the alligators."

February zj. "Daddy says this is the dullest, most boring river journey he has ever made; and we are counting the hours of the three more days yet to be spent before Cuyaba is reached. We are still in swamp country, though no longer in the Paraguay River, for we entered the Sao Lourenco the day before yesterday, and the Cuyaba River last night. The Sao Lourenco is noted for its mosquitoes, which breed in the extensive swamps, and on Wednesday night they came aboard in clouds. The roof of the place where we eat and sleep was black—literally black—with them! We had to sleep with shirts drawn over our heads, leaving no breathing-hole, our feet wrapped in another shirt, and a mackintosh over the body. Termite ants were another pest. They invaded us for about a couple of hours, fluttering round the lamps till their wings dropped off, and then wriggling over floor and table in their millions.

"We saw some capibara today. One of them stood on the bank not eighteen yards away as we went past. It is a tragedy that the whole of this country for hundreds of miles is absolutely useless and uninhabitable. We go up river at a walking pace—so slowly that today we were overhauled by two men in a canoe, who were soon out of sight ahead.

"There is no entertainment in staring at the river bank, for it has altered in no way since we left Corumba. There is a tangle of convolvulus creeper and wild banana-like dock leaves—with onfa (jaguar) holes, worn bare with use, coming out to the edge of the water. Behind, and towering above, are thick trees of various sorts, extending about twenty yards back, and then the swamps begin, stretching as far as the eye can see, broken only by isolated clumps of swamp trees like mangroves. Occasionally there is to be seen a foetid pool, lurking-place of anacondas and nursery of mosquitoes. Sometimes the swamp comes right up to the river and there is no bank at all. There are many vultures and diving birds like cormorants, with long necks which make them resemble snakes when swimming. The jacares (alligators) live only where there is bare mud or sand where they can bask.

"Heavy rain has fallen today and the temperature has dropped to about the same as an English summer. The weather is supposed to grow cooler now anyway, as we are nearing the dry season. Daddy says he has never been in this region in the really dry season, and thinks it probable that the insects will not be as bad as they were in 1920.

"A new pest has come aboard today. It is the mutaca, a sort of h< fly with a nasty sting. We smashed many, but Daddy and Raleigh were stung. All of us are of course covered with mosquito-bites.

"What we miss a good deal is fruit, and none can be obtained till wc reach Cuyaba. Otherwise the food is good. Lack of exercise is annoying, and in Cuyaba we intend to make up for it by having a good long walk every day. As a matter of fact, we have had almost no exercise since leaving Rio, except for a fairly long hike up the railway track while we were held up for a day or two at Aquidauana. I do 'press-ups' whenever I can, but so crowded are we that even this is not easy.

"Raleigh is a funny chap. He calls Portuguese 'this damn jabbering language', and makes no attempt to learn it. Instead he gets mad at everyone because they don't speak English. Beyond fa% favor and obrigado he can say nothing to them—or is too shy to try. I can now keep up a fair conversation provided the person I am speaking to answers slowly and distinctly. They mix it with a lot of Spanish here, owing to the proximity of Bolivia and Paraguay."

March 4. "Cuyaba at last—and not so bad as I had been led to expect! The hotel is quite clean, and the food excellent. We are feeding up now, and I hope to put on ten pounds before leaving, as we need extra flesh to carry us over hungry periods during the expedition. The river journey took eight days—rather a long time to be cooped up on a tiny vessel like the Iguatemiy and confined to the same spot on the same bench. Yesterday we went for a walk in the bush, and joyed at the freedom to take exercise. Today we go shooting for the first time—not at birds, but at objects put up for practice.

"We called on Frederico, the mule man, but he is away until Sunday. His son says there will be no difficulty about getting the twelve mules we require. The sertanista ('guide* is near enough) Daddy wanted has died; and Vagabundo has gone into the sertao with someone else, which is a great pity, for I've heard so much about that dog that I wanted to see him. There is an American missionary here who has a lot of back numbers of the Cosmopolitan and other magazines, and we are going along tonight to swap books with him. ..."

March 5. "Yesterday Raleigh and I tried out our guns. They are very accurate, but make a hell of a row 1 We expended twenty cartridges, which leaves us 180 for future practice.

"I hear that on leaving Cuyaba we have scrub country for a d travel which will bring us to the plateau; then small scrub and grass all the way to Bacairy Post; and about two days beyond that wc will get our first game. In the first day or two we may be able to photograph a gorged sucuri (anaconda) if anyone can direct us to one in the vicinity. . . ."

April 14. "The mail has come in—the last we shall get, for on the 20th we leave. The heat here is something like Jamaica at its very hottest, but Raleigh and I go out daily to a stream on the Rosario road and stay in the water for an hour or so. It's not very refreshing, for its temperature is about the same as the air, but the evaporation in drying off afterwards cools us down.

"I have tried to get some sketching done here, but the subjects are so commonplace that I can't put any pep into them, and the result is they are not worth a damn! What I am always looking for is a really good subject, and then possibly something worth while will be produced. When we reach the place where the first inscriptions are to be seen I shall have to sketch, for all those things must be carefully copied.

"You would be amused to see me with a fortnight's growth of beard. I shall not shave again for many months. We have been wearing our boots so as to break them in, and Raleigh's feet are covered with patches of Johnson's plaster, but he is keener than ever now we are nearing the day of departure. We seem to be a hell of a time waiting for animals, but it is all the fault of Frederico and his lies. It was hopeless trying to get anything done with him, so we are now dealing with another chap called Orlando. I think the mules arrived today. The two dogs, Chulim and Pastor, are getting very bravo, and rush at any visitor who dares tap at the door.

"There was some rather bad shooting at Coxipo, a league distant. A fellow named Reginaldo with six companions, all of whom we saw leave Gama's Hotel here in the morning, were waylaid by a gang with a grudge against them. There had been a quarrel over gunplay and drink in the Casamunga diamond fields, and they met at Coxipo and shot it out. Reginaldo and one of the bandits were killed, and two others seriously wounded. The police went to work on the case after a few days, and over a cup of coffee asked the murderers why they did it! Nothing more has happened. ..."

Extracts from my father's letter of April 14:

"We have had the usual delays incidental to this continent of mananas, but are due to get away in a few days. We start with every hope of a successful issue. . . .

"We are all three very well. There are two dogs rejoicing in the names of Pastor and Chulim; two horses and eight mules; a polite assistant named Gardenia, who has an unrestrained appetite for advances—or providencias, as they euphemistically call them here—and a hard-working negroid mougo who answers to everyone's call. These two men will be released as soon as we find traces of wild Indians, as their colour involves trouble and suspicion.

"It has been abominably hot and very rainy, but things are settling down now into the cool and dry season.

"Jack talks a fair amount of Portuguese, and understands a modicum of what is said to him. Raleigh cannot acquire a blessed word!

"A ranching friend of mine told me that since a boy he and his people have sat in the verandah of their house, six days north of this, and listened to the strange noise coming periodically out of the northern forests. 1 Ic describes it as the hiss, as it were, of a rocket or great shell soaring into the air and plunging again into the forest with a 'boom-m-m-boom-m\ 1 Ic has no idea what it might be, but I think it is probably a meteorological phenomenon connected with high volcanic areas, such as my* people at Darjeeling, where discharges of artillery were heard between monsoons. Other parts of this lofty region give out 'booms' and snoring sounds, to the terror of the people who hear.

"My ranching friend tells me that near his place there is in the River Paranatinga a long rectangular rock pierced with three holes, the middle one being closed and apparently cemented at both ends. Behind it, somewhat carefully concealed, is an inscription of fourteen strange characters. He is going to take us there to photograph it. An Indian on his ranch knows of a rock covered with such characters, and this we also propose to visit.

"Another man, who lives up on the chapada —the high plateau just north of this, which was once the coastline of the old island—tells me he has seen the skeletons of large animals and petrified trees, and knows of inscriptions, and even foundations of prehistoric buildings, on the same chapada. It is, of course, the border of our region. One wide grassy plain near here has in its centre a great stone carved in the shape of a mushroom —a mysterious and inexplicable monument.

"The intermediate building between 'Z' and the point where we leave civilization is described by the Indians as a sort of fat tower of stone. They are thoroughly scared of it because they say at night a light shines from door and windows 1 I suspect this to be the 'Light that Never Goes Out*. Another reason for their fear of it is that it stands in the territory of the troglodyte Morcegos, the people who live in pits, caves, and sometimes in thickly foliaged trees.

"Some little time ago, but since I first drew attention to Matto Gr by my activities, an educated Brazilian of this town, together with an army officer engaged in surveying a river, were told by the Indians about a city to the north. The offer was made to take them there if they dared face the bad savages. The city, said the Indians, had low stone buildings with many streets set at right angles to one another, but there were also some big buildings and a great temple, in which was a large disc cut out of rock crystal. A river running through the forest beside the city fell over a big fall whose roar could be heard for leagues, and below the fall the river seemed to widen out into a ^reat lake emptying itself thev had

no notion where. In the quiet water below the fall was the figure of a man carved in white rock (quartz, perhaps, or rock crystal), which moved to and fro with the force of the current.

"This sounds like the 1753 city, but the locality doesn't tally with my calculations at all. We might visit it on the way over, or, if circumstances permit, while we are* at *Z\

"My rancher friend told me he brought to Cuyaba an Indian of a remote and difficult tribe, and took him into the big churches here thinking he would be impressed. 'This is nothing!' he said. 'Where I live, but some distance to travel, are buildings greater, loftier, and finer than this. They too have great doors and windows, and in the middle is a tall pillar bearing a large crystal whose light illuminates the interior and dazzles the eyes!'

"So far we are getting a lot of rain and it is very hot. I don't remember perspiring so much for many years—yet it is only 80 degrees in the shade "

Jack takes up the tale again:

Bacairy Post, May 16, 1925. "We arrived here yesterday after a rather strenuous journey from Cuyaba. We left on April 20, with a dozen animals; the horses in fairly good condition, but the mules thin. It seems that the place where they were sent to be fattened up had half-starved them instead, so as to make a few extra milreis 1

"At the start we went very slowly on account of the animals, and camped the first night about two leagues from Cuyaba. During the night an ox collided with Raleigh's hammock, but apart from pitching him out no harm was done. The second night we camped three leagues on, and bathed in quite a good stream. The third night was spent in the higher chapada country, where we were in terror of the Saube ants eating our equipment. Next day we lost the way for the first time, having to retrace our steps some distance and camp on a side trail. Fortunately we cut the main one next day, and on reaching the house of a morador —a man who lives on the trail—we asked the distance to the Rio Manso. He told us four leagues, so we decided to make it that day—but it was about seven leagues, and darkness had fallen before we reached there.

"Daddy had gone on ahead at such a pace that we lost sight of him altogether, and when we came to a place where the trail forked we didn't know which to take. I spotted some marks made by a single horse on the larger trail, so we followed it and eventually arrived at the Rio Manso in pitch dark, to find he was not there! I discargoed at once and sent out Raleigh and Simao, one of the peons, to fire shots in the hope of getting a reply. Meanwhile we camped and made tea in the pitch dark, and when the others returned without him we thought he must have put up for the night with a morador. Next morning we sent out more signals but they were

unanswered; then, as we finished breakfast, he rode in after spending the night on the ground.

"We stayed in camp next day to rest ourselves and the animals, but were plagued v/ithgarapata ticks the whole time. Ticks of all sizes swarmed on the ground, and Raleigh was bitten so severely that his foot was poisoned. Next day we crossed the river on a batalao and camped in a deserted place where a morador had lived, finding there any amount of oranges.

"To cut things short, we missed the way again, and Raleigh gloomed all the way to the Rio Cuyaba, which we found impossible to cross owing to rapids and the weak condition of the animals. A fording-place was found higher up, and we had to unload the animals and make them swim across, sending over the cargo in a canoe we found there. Raleigh could do nothing because of his bad foot, so Daddy and I attended to the cargo, while the.peons looked after the animals. After a difficult passage we finally reached the house of Hermenegildo Galvao, where we stayed five days to feed up. I found that between Cuyaba and here I had gained seven pounds in weight, in spite of far less food. Raleigh has lost more than I gained, and it is he who seems to feel most the effects of the journey.

"Five days after leaving Senhor Galvao's place we reached the Rio Paranatinga, only to find that the Bacairy village was deserted and the canoe on the other side of the river. Someone had to swim over and get it, so I went—though I was scared stiff of things in the river, and felt rather like that time in Jamaica when Brian and I were chased by a shark. We camped in the village, and next day swam the animals over, and did the cargo in the same way as on the Cuyaba River. One league beyond we had to do it again, to cross a boggy stream; one league beyond that the whole back-breaking business had to be repeated. By this time we were absolutely fagged out, so we camped, and came into Bacairy Post yesterday morning.

"It is nice and fresh here, and just beyond the hills—about four miles away—is absolutely unexplored country. The schoolhousc has been put at our disposal, and we get our meals from the head of the Post, a decent fellow named Valdemira.

"Shortly after we arrived, about eight wild Indians from the Xingu —stark naked—came in to the Post. They lived about eight days down the river, and occasionally visit this place for the sake of curiosity and for the things they are given. There are five men, two women, and a child, and they are living in a hut by themselves. We gave them some guava cheese yesterday, and they liked it immensely. They are small people, about five feet two inches in height, and very well built. They eat only fish and vegetables—never meat. One woman had a very tine necklace of tiny discs cut from snail shells, which must have required tremendous patience to make. We offered her eight boxes of matches,

some tea, and some buckles, and she readily swapped. The necklace will be sent to the Museum of the American Indian in New York."

May 17. "Today we took some photos of the Mehinaku Indians which will of course go to the North American Newspaper Alliance. The first showed four of them with their bows and arrows, standing near a small stream by a strip of jungle. I am standing with them to show the difference in our heights. They just come up to my shoulder. The second picture shows them preparing to shoot arrows at fish in the water. The bows are bigger than the ones we had in the house at Seaton, and are over seven feet long, with six-foot arrows; but as these people are not so powerful, I can easily draw the bows to my ear.

"Last night we went to their hut and gave them a concert. I had my piccolo, Valdemira his guitar, and Daddy his banjo. It was a great success, though we were nearly choked with smoke.

"These Mehinakus tell us by signs that four hard days' travel to the north live the Macahirys, who are cannibals, and not over five feet tall. They may be the Morcegos, but I doubt it, as they use arrows, which the Morcegos have not yet come to.

"About three weeks' journey from here we expect to strike the waterfall mentioned by Hermenegildo Galvao, who heard about it from the Bacairy Indian Roberto, whom we visit tomorrow. It is entirely unknown to anyone, and Roberto was told of it by his father, who lived near there when the Bacairys were wild. It can be heard five leagues away, and there is to be seen an upright rock, protected from the waters, which is covered with painted pictures of men and horses. He also mentioned the watch tower, supposed to be about half-way to the city."

May 19. "A nice fresh day for my twenty-second birthday—the most interesting I have had up to now!

"Roberto came over here, and after being primed with Vinbo de Cajo told us some interesting things. He says it was the ambition of his life to go to this big waterfall where the inscriptions are, and settle there with his tribe, but now it is too late. Also, there are Morcegos and Caxibis there, and he is scared of them. We obtained the location from him together with a description of the country. The waterless desert is only one day's journey from end to end, and after that we come into grass country with no mato at all. His uncle talked about the cities, and he alleges that his very ancient ancestors made them. We leave here the day after tomorrow, and five days will see us in unknown country. I shall be glad when the peons leave us, as we are getting sick of them.

"You may be interested to hear what we eat while on the trail. At half past six in the morning we have one plate of porridge, two cups of tea, and one third of a cup of condensed milk; then, at half-past five in

the evening we have two cups of tea, two biscuits, goiabaaa or sardines, or one plate of cbarque and rice. Here we have been able to buy any amount oijarinha and sweet potato to help out the rice, and I do the cooking of it. We are also able to get some bones and a little mandioca. There are plenty of cows belonging to the Post, so fresh milk is obtainable in the mornings.

"We have clipped our beards, and feel better without them. I must be even heavier here than I was at Hermenegildo's, in spite of the journev, and I have never felt so well. Raleigh's foot has nearly healed, and Daddy is in first-rate condition. What we now look forward to is reaching Camp 15 and getting rid of the two peons.

"By the way, they say the Bacairys are dying off on account of fetish, for there is a fetish man in the village who hates them. Only yesterday a little girl died—of fetish, they say!"

May 20. "The photographs for N.A.N.A. have just been developed and there are some very good ones of the Mehinaku Indians, and of Daddy and myself. It is hard to develop successfully here as the water is so warm, and we were lucky to find the temperature of one stream as low as 70° Fahrenheit.

"Raleigh's other foot is swollen. He rubbed it or scratched it one morning, and in the afternoon when he took his sock off to bathe the skin came off with it, leaving a raw place. Now it has started to swell— and he has a raw place on his arm, too. What will happen when we really meet insects I don't know! There will be plenty of walking in about a week, and I hope his feet will stand it. Brian could have stood it much better, especially as we have had no hardships. 1 Daddy was saying today that the only ones he has had with him who were absolutely fit all through were Costin and Manley. Both of us are feeling damn good.

"Next time I write will probably be from Para—or 'Z' maybe!"

To Jack it was a grand adventure—the very thing he had been brought up to do, and kept himself fit for. My father's letters were more matter of fact. To him it was routine stuff, and his eyes were focused on the objective lying ahead of them. He speaks again:

Bacairy Post, Nlatto Grosso, May 20, 1925. "We reached here after rather unusual difficulties, which have given Jack and Raleigh an excellent initiation into the joys of travelling in the sertao. We lost our way three times, had endless bother with mules falling in the mud ot streams, and have been devoured by ticks. On one occasion, being too tar ahead, 1 missed the others. Returning to look for them, I was overtaken by the dark and forced to sleep on the open campo with saddle fi>r pillow,

1 Big-brother stuff! He may have been the most muscular, but I was ever the stronger constitutionally.— Ed.

thereby being covered with minute ticks which gave me no rest from scratching for over two weeks.

"Jack takes it well. He reached here stronger and fatter than he was in Rio. I am nervous about Raleigh's being able to stand the more difficult part of the journey, for on the trail the bite of a tick developed into a swollen and ulcerous foot, and of late he has been scratching again till great lumps of skin have come away.

"To Jack's great delight we have seen the first of the wild Indians here, naked savages from the Xingu. I have sent twenty-five excellent photographs of them to N.A.N.A.

"I saw the Indian chief Roberto and had a talk with him. Under the expanding influence of wine he corroborated all my Cuyaba friend told me, and more. Owing to what his grandfather had told him, he always wanted to make the journey to the waterfall, but is now too old. He is of the opinion that bad Indians are numerous there, but committed himself to the statement that his ancestors had built the old cities. This I am inclined to doubt, for he, like the Mehinaku Indians, is of the brown or Polynesian type, and it is the fair or red type I associate with the cities.

"The Bacairys are dying out like flies of fever and fetishism. Every malady is the work of a fetish! Without question it is the finest opportunity for a missionary if only one with medical experience would come, for he could contact the wild Indians and tame them.

"Needless to say, I was cheated over mules and pretty well everything else. It was unfortunate that the man supposed to provide them failed me, forcing me to get them at very short notice from another—and in Cuyaba commercial honesty is not dreamed of! They turned out to be so bad that it was necessary to buy mules on the way, and for this purpose—as well as to cure Raleigh's foot—we stopped five days at the/agenda of my friend, Hermenegildo Galvao. The peons are useless too, and, on account of the wild Indians, are terrified at the prospect of continuing north.

"Jack is pretty good at Portuguese now, but Raleigh still has only two words. I prefer Spanish, but Portuguese is more important for Brazilian developments, and of course I am pretty fluent.

"A letter will be sent back from the last point, where out peons return and leave us to our own devices. I expect to be in touch with the old civilization within a month, and to be at the main objective in August. Thereafter, our fate is in the lap of the gods!"

Finally comes the last word from him, dated May 29, 1925, and sent back with the peons. After this not another thing was heard from them, and to this day their fate has remained a mystery.

"The attempt to write is fraught with much difficulty owing to the legions of flies that pester one from dawn till dark—and sometimes all

through the night! The worst are the tiny ones smaller than a pinhead, almost invisible, but stinging like a mosquito. Clouds of them are always present. Millions of bees add to the plague, and other bugs galore. The stinging horrors get all over one's hands, and madden. Even the head nets won't keep them out. As for mosquito nets, the pests fly through them!

"We hope to get through this region in a few days, and arc camped here for a couple of days to arrange for the return of the peons, who are anxious to get back, having had enough of it—and I don't blame them. We go on with eight animals—three saddle mules, four cargo mules, and a madrinha, a leading animal which keeps the others together. Jack is well and fit, getting stronger every day even though he suffers a bit from the insects. I myself am bitten or stung by ticks, and these piums, as they call the tiny ones, all over the body. Raleigh I am anxious about. He still has one leg in a bandage, but won't go back. So far we have plenty of food, and no need to walk, but I am not sure how long this will last. There may be so little for the animals to eat. I cannot hope to stand up to this journey better than Jack or Raleigh, but I had to do it. Years tell, in spite of the spirit of enthusiasm.

"I calculate to contact the Indians in about a week or ten days, when we should be able to reach the waterfall so much talked about.

"Here we are at Dead Horse Camp, Lat. u° 43' S. and 54 0 35' \\'., the spot where my horse died in 1920. Only his white bones remain. We can bathe ourselves here, but the insects make it a matter of great haste. Nevertheless, the season is good. It is very cold at night, and fresh in the morning; but insects and heat come by mid-day, and from then till six o'clock in the evening it is sheer misery in camp.

"You need have no fear of any failure. . . ."

Those last words he wrote to my mother come to me like an echo across the twenty-six years elapsed since then. "You need have no fear of any failure. . . ."

THE NEW PRESTER JOHN

IT was in 1927, when I was stationed up in the Mountain Section of the Central Railway of Peru, that a call came from Lima saying that there had arrived in town a French civil engineer named Roger Courteville, who claimed to have come across my father in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, a month or two earlier.

I rushed down to Lima and met M. Courteville, who told me that he and his wife had crossed from Atlantic to Pacific by car, via La Paz. When coming through the sertSo of Minas Gerais, he said, they met seated by the wayside an old man, ragged and sick, who on being questioned replied that his name was Fawcett.

"Did he say anything else?" I asked.

"He seemed confused, and not all there—as though he had come through terrible hardships."

M. Courteville was anxious to persuade me to contact the North American Newspaper Alliance, raise funds for an expedition, and return to find the old man.

"I didn't know anything about Colonel Fawcett till I reached here," he explained. "Had I known we could have brought him with us. Anyway, it shouldn't be hard to find him if we go back—there are very few Gringos in that district."

I was sceptical, but reluctant to dismiss the story in case it might be true. After all, it could 'be! However, N.A.N.A. thought otherwise, and no funds were forthcoming. It was not yet the heyday of the big, well-

292

financed, and top-heavy 'rescue' party, with movie apparatus and two-way radio.

The following year N.A.N.A. organized a big expedition led by Commander George Dyott (whom I met in Peru in 1924) to investigate my father's fate, and it left Cuyaba in May, 1928. They made across country to the Kuliseu River, coming to a village of the Nafaqua Indians. In the hut of the chief, Aloique, Commander Dyott saw a metal uniform case, and the chief's son wore round his neck a string with a brass tag bearing the name of the maker of this trunk, Silver & Co. of London.

Aloique said the trunk was given to him by a Caraiba (white man) who had come with two others, younger, and both lame. The three had been taken by Aloique to a Kalapalo Indian village on the Kuluene River, after which they crossed the river and continued east. For five days the smoke of their camp fires was seen, and then no more.

The Dyott expedition returned with no proof of anything—not even that the Fawcett party had been there, for while the uniform case, identified by the maker, had belonged to my father, it was one discarded by him in 1920. It was Commander Dyott's belief that my father had been killed; but I have given the evidence, and leave it to the reader to judge. We of the family could not accept it as in any way conclusive.

The next expedition to solve the mystery was led by a journalist, Albert de Winton; and in 1930 it reached the same Kalapalo village where de Winton believed the Fawcett party was wiped out. He never came out alive, and nothing was proved.

There was a sensation in 1932 when a Swiss trapper named Stctan Rattin came out of Matto Grosso with a tale that my father was a prisoner of an Indian tribe north of the River Bomfin, a tributary of the Sao Manoel River. He claimed to have spoken with him, and this was his statement:

"Towards sunset on October 16, 1931, 1 and my two companions were washing our clothes in a stream (a tributary of the River Iguassu Ximary) when we suddenly noticed we were surrounded by Indians. I went up to them and asked them whether they could give us some chicha. I had some difficulty in communicating with them as they did not speak Guarany, though they understood a few words. They t us to their camp, where there were about 250 men and a large number of women and children. They were all squatting on the ground drinking chicha. We sat down with the chief and about thirty others.

After sunset there suddenly appeared an old man clad in skins, with a long yellowish-white beard and long hair. I saw immediately that he was a white man. The chief gave him a severe look and said something to the others. Four or five Indians left our group and pot the old man to sit down with them a few yards away from us. Eic