2 Deities and Demons

No other animal elicits such fascination and fear as the shark. Part of the reason is its power. With the occasional exception of humans and killer whales, the shark rules among all the myriad life forms of the sea. Another part of the shark’s hold on our imaginations derives from its elusiveness. Even now, we know relatively little about shark behaviour. They appear suddenly, often out of the gloom of deeper water, at which point they may flick away or circle. Or they may circle and attack, or hit and run. Or they may remain to devour. But what appears as unpredictable or capricious is really an indication of our own ignorance. The response in the West to this ignorance has been the castigation of sharks as vicious demons of the deep, without much regard for their size or species. By contrast, the cultures that have lived most closely with sharks have traditionally viewed them not as monsters but as religious entities.

Pacific islanders invested sharks with spiritual powers. Like violent storms and volcanoes, sharks were forces over which they had no control. These people couldn’t net their beaches or build steel boats any more than they could engineer levees, dikes or sea walls to protect themselves from typhoons and volcanic eruptions. So instead they chose to stand in awe of the natural forces that rendered them helpless. Polynesians of the South Pacific worshipped the shark god, Kauhuhu. The people of Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands believed that sharks were embodiments of their ancestors and in some cases ghosts of the more recently departed. The Tlingit of what is now south-west Alaska and the coast of British Columbia used the dogshark as a decorative element to remind themselves of the myth of a woman who was carried off by a shark and subsequently became one. The Songlines of the Australian Aborigines contain references to a bloodstain on the rocks of Chasm Island, where the reddish coloration on the rocks is believed to be evidence of the attack by the tiger shark Bangudya on the dolphin-man, a gentle hybrid.1 Hawaiians developed the most elaborate beliefs featuring sharks and worshipped them as gods, just as they deified Pele, the fire goddess of the volcanoes. Sharks and volcanoes were seen as uncontrollable natural forces that held the power of life and death. In earlier times the Hawaiians and the Solomon Islanders made human sacrifices, casting ritually dismembered victims or even living ones into the ocean at spots where there were known to be a lot of sharks. Believing that sharks desired human sacrifice seemed logical enough, since sharks periodically took people of their own accord.

Bowl with hammerhead-shark design, c. 600–800 AD, Pre-Columbian (Panama Cocle).

For Pacific islanders, sharks have always been part of life: background threats, reasons to be cautious and occasional killers. Travellers between islands accepted that they were unlikely to drown if they were to capsize at sea; an oceanic whitetip would find them first. Tiger sharks paid periodic visits to these tropical islands, snatching a swimmer or sometimes overturning a dugout canoe. The canoe would be found empty and adrift, and people would assume that a shark was the cause. Spear fishermen knew they were especially vulnerable and took precautions. They immediately crushed the skulls of caught fish between their teeth to stop the fluttering of the wounded fish, and they would suspend all spear fishing for three days after a tiger shark sighting. While the reef sharks that they typically encountered were smaller and less aggressive than tiger sharks, even a minor bite could be fatal without antibiotics or medical care. Polynesian peoples therefore assumed an attitude of respect for the shark’s power and majesty within its own watery realm.

That respect could take the form of deification, particularly in Hawaii. In fact, early Hawaiians had nine named shark gods and demigods, not counting the beneficent guardian spirits and family protectors known as aumakua. Chief among their gods and goddesses was Ka’ahupahau, who lived near Pu’uloa (now Pearl Harbor) and protected the island of Oahu from other sharks. She and her brother, Kahi’uka (which means ‘slapping tail’), were born as humans and later transformed into sharks; however, they retained some memory of their previous lives. While she was still a human, Ka’ahupahau was famous for being a redhead; whether this singularity among Hawaiians was related to her transformation is unclear. What is certain is that imperiousness was part of Ka’ahupahau’s characterization. According to legends, worshippers were bringing leis – flower necklaces – to her when a local girl demanded the loveliest of the leis for herself. Scolded for her disrespect, the girl snatched the lei and ran off, offending Ka’ahupahau. When the girl swam out to a rock, the shark goddess spied her and said to the other sharks, ‘That girl is spoiled and selfish and has no respect. She deserves to die.’ So one of the sharks carried out the goddess’s wishes by dragging the girl into the sea and killing her. With this resolution we might expect the legend to end, but the legend of Ka’ahupahau is a complex parable. The shark goddess was still new to her power and divinity when she said that the girl should die, and when she learned of the girl’s death, she was anguished at the glib way she had exercised her power. Ka’ahupahau pledged that sharks would never again attack humans at Pu’uloa. According to myth, the people of Oahu repaid Ka’ahupahau for her protection by feeding her and her brother and grooming them, removing the barnacles and remoras from their skin.2

The shark god Kamohoalii could transform himself into human shape. Kamohoalii was the favoured brother of Pele, the fire goddess who, because of the several active volcanoes on the islands, ruled most powerfully over Hawaii. The most sacred spot to worship Kamohoalii was, in fact, on the rim of the Kilauea crater on the island of Hawaii, but at one time every piece of land jutting into the sea on Molokai enjoyed some sort of shrine dedicated to Kamohoalii. Kapen’apua, usually identified as the young brother of Pele and Kamohoalii, was seen as a kind of trickster, able to assume the form of a bird and perform feats of magic, including the calming of two legendary colliding hills that destroyed all canoes that tried to pass between them.3 Pele’s cousin Keali’ikau-o-Kau was the shark god who protected the Ka’u people, on the Big Island of Hawaii, from sharks. The legend tells that he had an affair with a young woman who gave birth to a beautiful, benevolent green shark.

Sharks-as-ancestors myths were common throughout the Polynesian islands. On the Big Island of Hawaii, the main shark god Kua was believed to be the ancestor of the Ka’u people.4 Of all Hawaiian tribes, the Ka’u could be said to live closest to their origins, since they made their home at South Point, the southernmost spot in the Hawaiian chain and the likely landing place for the original settlers of the islands. So it seems appropriate that they would retain one of the central Polynesian beliefs. In French Polynesia, islanders also believed that their ancestors manifested themselves in the form of a shark called Taputapua, which could be called upon to take part in family disputes. The common reluctance of spear fishermen to work after a domestic argument follows logically from this belief; the fishermen feared that their angry wives might invoke Taputapua to settle the argument at sea. But sharks as ancestors, the domestication of a deity and a natural threat, must have also helped to bolster the courage of these people who routinely took to the open sea in dugout canoes. Throughout Polynesia, islanders made offerings to the shark gods before ocean voyages, asking for protection and favourable winds during their journeys beyond sight of land. In fact, Taputapua is still thought to be available for emergencies, such as transporting capsized fishermen to shore. It must help the fishermen to believe that their Taputapua, or ancestral spirits, might be available to protect them.

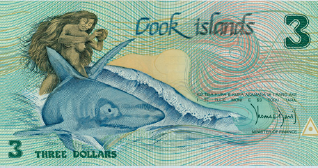

One Cook Island legend, that of Ina and the shark, is commemorated on the country’s currency. Ina was the love of Tinirau, the god of the ocean who lived on a floating island. One day, Ina tried to jump into the ocean to swim to Tinirau, but the surf kept flinging her back to shore. So she asked the fish to help her. But when these fish proved too weak to pull her past the waves, she beat them with a stick, scarring them – which is how angel fish acquired their stripes. Next Ina asked a shark to help, and he agreed. Ina brought along coconuts for her journey, and when she became thirsty the shark lifted his dorsal fin for her to crack the coconut. After a while Ina relieved herself; the shark asked her not to do so again. According to the legend, Ina’s poor manners explain why shark meat sometimes has a slight urine taste. When Ina became thirsty again, she decided to crack her second coconut on the shark’s head. In one version of the story, Ina’s repeated attempts to crack her coconut explain how the hammerhead got its head. In another version, her cracking of the coconut explains why sharks have a bump on the tops of their heads, known to Cook Islanders as Ina’s bump. Regardless, the shark had enough of Ina’s behaviour and tossed her off his back. Ina would have drowned if not for Tekea the Great, the King of the Sharks, who rose up from the bottom of the ocean to save her and transport her the rest of the way to Tinirau’s floating island.5

Ina and the Shark Legend, depicted on Cook Islands currency. |

|

In Sri Lanka the pearl divers attended ceremonies with their local shark charmers before the day of diving. These shark charmers were believed to have hereditary powers from a mysterious higher authority that was recognized and respected by the sharks.6 No doubt the divers were calmer in the water, more graceful and therefore less likely to attract sharks.

The Marshall Islanders fought religious wars over sharks when one tribe showed disrespect to the sacred shark of another tribe. If, for instance, one tribesman caught and killed the totem shark or ray of a rival tribe, the offended tribe would demand an apology and a pledge that the offence would not occur again. If these terms were not met, then a holy war would ensue.7

The coastal people of Papua New Guinea have kept alive the ancient religious practice of shark calling, which is seen as both an act of reverence and proof of manhood and courage. These people have long believed that sharks contain the spirits of their ancestors, but they have what may seem to us an odd way of showing it. Armed with only a club and a noose on a short pole, men go out to sea (usually alone) in dugout canoes to capture sharks. The fisherman uses a rattle made from shells and coconuts to attract a shark; he then slips the noose over the shark’s head and wrestles it into the canoe where, operating in very close quarters, he clubs it to death. Because of the narrowness of the canoes, this ritual requires amazing skill and balance as well as courage. Once ashore, the shark is ritually butchered, with prescribed cuts going to the fisherman’s family and the chief, then to the rest of the community. Even today on the island of Kontu, eating a shark killed and prepared in the customary ancient manner is considered a blessing for the whole village.8

For Westerners, it is easy to see the Pacific islanders’ deification and domestication of sharks as little more than transparent attempts to manage their own fears of the powerful, capricious forces encountered in their daily lives. Aboriginal people, in an effort to explain the mysteries of shark behaviour, attributed human qualities and chieftain characteristics to sharks, thus imagining not only a great shark like Ka’ahupahau who learns from her mistake, but also family sharks, ancestral sharks, benevolent sharks and saviour sharks. Sharks are both elusive and commonly encountered, so it seems only natural that they would inspire divinity myths. Whereas the American and European response, particularly in the twentieth century, has been to sensationalize shark encounters and fan the flames of shark terror, Pacific islanders have wisely preferred to minimize their fear of the unknown and the unpredictable by taming it through mythology.

More complicated are the shark-man myths, common throughout the South and Central Pacific. In ancient Japan, the mythological god most feared was the storm god known as ‘shark-man’, who betrayed people’s trust in nature by transforming typically benign natural forces of wind and rain into an overwhelmingly destructive storm like a typhoon. In the Solomons, myths divided sharks into good and bad ones. The good sharks, often believed to be the spirits of ancestors, were said to guide fisherman back to safe harbour and protect swimmers from alien sharks, even to transform themselves into stingrays and transport endangered swimmers to shore. But in other myths sharks represent not benevolence but the two-faced malevolence of our own kind, with evil men taking the form of sharks to commit their murders and changing back to human form during the day. Hawaiian mythology includes numerous stories of shark-men, identifiable by the pattern of shark jaws on their backs, who were able to alter their forms, sometimes under the full moon, like werewolves. A common event in many of these myths features a strange man warning swimmers to stay out of the water because of sharks. When the swimmers scoff at the stranger and ignore his warning, he transforms himself into a shark and devours them. As in were-wolf mythology, the demonic masquerade is discovered when villagers hunt the shark, only later to find a strange man, pierced with their spears, dying on the beach.

The patterns that exist across the Pacific represent sharks as a higher power, whether a deity or merely a powerful force of nature. The sharks might maim or kill, but the violence they inflict is neither treacherous nor personal. Shark-men are the exceptions and the dangerous aberrations; acts of malevolence, wanton and personal attacks, occur only when sharks are in this unnatural form, hybridized with human qualities such as pride, vengeance, blood lust and cruelty. Ka’ahupahau, not yet fully transformed into the shark deity, reacts angrily and imperiously orders the death of the disobedient girl. The shark goddess is not malicious, however. Once she assumes her new status, she learns from her abuse of power and acquires majesty. By contrast, the shark-man who haunts the beach, switching back and forth between human and shark forms, is a psychopath or a demon – his anger at being laughed at is only an excuse for doing what he wants to do.

The shared quality of these shark-men and partial transformations is treachery: men using their power, their shark forms, to commit the violence that is harboured in their human hearts. The Pacific peoples recognized that sharks are by nature capable of great violence but not of anything malicious or demonic. Sharks kill randomly and indifferently. Only our own species can muster the desire to commit violence for the perverse pleasure of it. Implicit in the shark-man myths is the belief that it takes a hybrid to make a monster: the natural power and armament of the shark combined with the human possibilities of a Jack the Ripper or an Iago.

A Hawaiian shark-tooth weapon.

Interestingly, Hawaiians of centuries past also contrived challenges to the sharks that they revered. They held gladiator contests between particularly brave young men and the shark gods at what is now Pearl Harbor, on the south shore of Oahu. Into a pen of lava rocks they lured sharks with bait, often including human flesh. They pitted these sharks against swimmers armed with a single spear, tipped with a shark tooth. Since the sharks had many teeth and their challengers only one, the sharks usually prevailed, thus reinforcing their majesty and divinity in a cloud of blood and carnage as the crowd looked on. Occasionally, however, a young man with his spear succeeded in slicing open a shark’s belly and disembowelling it, in which case human skill and resourcefulness would be celebrated for having defeated those of the god.

|

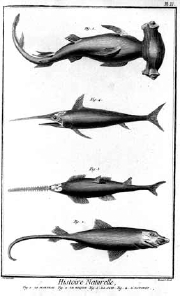

An illustration from Diderot’s Encyclopaedia showing a hammerhead shark. |

A similar desire, not just to get the occasional edge over nature, but to rule it, lies at the base of our Western attitude towards sharks. Within the European tradition, sharks have been demonized as far back as Greek mythology. Lamia was a beautiful queen of Libya pursued by the ever-lecherous Zeus. When his wife, Hera discovered their involvement and the children they’d had together, she stole the children. Lamia went mad from grief, becoming a demon that snatched, killed and ate the children of other mothers. Her mania altered her features, making her hideous; it even changed her form. The word lamia means ‘dangerous lone shark’. Often Lamia is described not as a shark or sea creature, but as a night-haunting demon that preys on young children, a kind of bogeywoman. Still, it’s intriguing to see this early connection between female power, motherhood driven to murderous madness and the shark. Later pluralized, Lamia became the ghostly, man-eating, multiple monster, Lamiai, whence the lamnid sharks (including the white shark) derive their name.9

Although Herodotus, writing in 492 BC, described hordes of ‘monsters’ devouring the shipwrecked soldiers of the Persian fleet, our contemporary terror of sharks really dates from another, much more recent, war – World War II.10 The numbers of actual deaths due to shark attacks were minuscule in comparison to the tens of millions killed, starved and exterminated in the course of the six-year, worldwide war; still, the fear of sharks loomed large in the imaginations of British, Japanese and American air force and naval personnel. The US Navy devised several ‘shark repellents’ which were merely smelly dyes that briefly clouded the water. These were widely used, although none of them proved the least bit effective. But sailors and airmen needed something to believe in when they ventured into ‘shark-infested waters’.

This popular terror can be traced to three major sinkings: two British transports torpedoed off South Africa early in the war and one US cruiser torpedoed in the Philippine Sea just days before the Japanese capitulation in 1945. The first of these disasters was the Laconia, a Cunard liner converted to a British armed merchant cruiser and transport, attacked and sunk on 12 September 1942 by a German U-boat 200 miles south of Ascension Island, just below the equator. The Laconia was carrying 2,715 passengers, including 1,783 Italian prisoners of war. She went down quickly, destroying many of the lifeboats. Still, most of the passengers made it into the water. Appalled by the vast number of survivors bobbing in the ocean, the U-boat crew surfaced and began picking up survivors. It also radioed British ships in the area, alerting them to the disaster. Perhaps because of the many hundreds of Italian pows, a second U-boat arrived to help in the recovery. Unfortunately for the survivors, these U-boats were sighted by an American air patrol and, although the German submarines displayed red crosses on their decks, American aircraft began to bomb and strafe them. The German response was to hastily force the survivors back into the sea. It was believed that the sound of the Laconia’s exploding boilers, rather like a dinner bell, first attracted the sharks. Whatever the reason, oceanic whitetips arrived soon after the sinking and remained close by, persistently circling and occasionally attacking, for the three days until the last survivors were rescued. There were 1,111 survivors. Of the 1,672 who died, an unknown number were victims of shark attacks. No details about causes of death were ever published. In fact, wartime censorship suppressed most information about maritime disasters during World War II.

Considering the lack of published information about sinkings and downed aircraft, it seems surprising that the shark attacks associated with wartime maritime disasters were so widely known. But they were avidly repeated, perhaps even exaggerated, because the sailors and airmen knew that military censorship suppressed and minimized the frightening details. Eyewitness reports contained in the log records of the Alfonso de Albuquerque, the ship that rescued survivors of the Nova Scotia sinking, were not released for years after the British transport went down. The Nova Scotia was torpedoed off Durban, South Africa, on 28 November 1942; it remains the worst maritime disaster to have occurred in that region. Of its 1,000 passengers, only 192 survived. According to the rescuing ship’s log, at least a quarter of those who died in the water were killed by sharks. Oceanic whitetips are common in the deeper waters of the Indian Ocean. Because of its many whale-processing factories, Durban also enjoyed considerable attention from white sharks and huge tiger sharks, hordes of which would follow the whaling ships into port. So, added to the usual reluctance of military authorities to allow publication of information that might be considered inflammatory was the historical local resistance to any linkage between whaling and shark attacks on Durban beaches. According to researcher Marie Levine’s crucial study, more than half of all South African shark attacks from 1940 until 1975 occurred on the Natal coast and when the whaling stations closed, in the late 1970s, shark attacks fell off sharply in the Durban area.11 And yet local rumour reported these statistics well before the South African authorities released information, just as naval gossip had proved the more reliable source for details of naval disasters.

The sinking of the USS Indianapolis resulted in the most sensational (and sensationalized) shark attacks in recorded history. The Benchley–Spielberg character Quint, from Jaws, summarizes the Indianapolis story this way, intending to emphasize the most inflammatory details:

Eleven hundred men went into the water . . . Didn’t see the first shark for about a half an hour. Tiger. 13-footer . . . shark comes to the nearest man, that man he starts poundin’ and hollerin’ and screamin’ and sometimes the shark go away . . . but sometimes he wouldn’t go away. Sometimes that shark he looks right into ya. Right into your eyes. And, you know, the thing about a shark . . . he’s got lifeless eyes. Black eyes. Like a doll’s eyes. When he comes at ya, doesn’t seem to be living . . . until he bites ya, and those black eyes roll over white and then . . . ah then you hear that terrible high-pitched screamin’. The ocean turns red . . . and they rip you to pieces. You know by the end of that first dawn, lost a hundred men. I don’t know how many sharks, maybe a thousand. I know how many men, they averaged six an hour . . . I bumped into a friend of mine, Herbie Robinson . . . I thought he was asleep. I reached over to wake him up. Bobbed up, down in the water just like a kinda top. Upended. Well, he’d been bitten in half below the waist . . . So, eleven hundred men went in the water; 316 men come out and the sharks took the rest, June the 29th, 1945.12

The actual date was 30 July 1945, and considerably fewer than 1,100 men made it out of the ship alive. The Indianapolis’ total crew was 1,196. Since the ship sank in twelve minutes, just after midnight when most crewmen were asleep, historians have estimated that 300 men were trapped below decks or immediately drowned. About 900 men survived the sinking, and 317 ultimately survived the ordeal,13 meaning that 600 men died in the water. Since the Indianapolis had been on a secret mission to deliver parts of the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ to the staging area on the island of Tinian, she was not listed on regular navy schedules and was therefore vulnerable to navy error. Her SOS signals were ignored; she was overdue for three days but not listed as missing when she failed to show up at Leyte, in the Philippines. The US Navy had reports of Japanese submarines in the vicinity but failed to inform the Indianapolis or to provide destroyer escort, as requested by the ship’s captain. The US Navy court-martialled the captain rather than admit that any of its own lapses and procedures might have been to blame for leaving 900 men drifting in the open ocean without food or water for nearly five days, during which time the survivors sustained four full days of shark attacks. Captain McVey was restored to duty a year after the war but took his own life in 1968.14

Perhaps 200 sailors from the Indianapolis were victims of shark attacks, an average of about 50 men per day.15 No doubt many of the other 400 casualties were consumed by sharks after dying from other causes: untreated wounds, hypothermia, dehydration, kidney failure from drinking salt water and drowning. There were very few rafts. The life jackets used by the US Navy became waterlogged within a day or two. By the time the first aircraft spotted the survivors, many hundreds of sharks had gathered. The survivors were too tired to fight, and attacks were routine. The stories about these shark attacks are grisly – sharks assaulting inflatable rafts, sharks attacking in waves – but even so, twice as many sailors died from exposure to the elements as from exposure to hungry sharks. Yet it’s the sharks – not the other natural causes of death or the Navy’s grotesque failures – that have made the USS Indianapolis famous.

The actual survivors of the disaster were much less dramatic than Quint, Benchley’s fictional survivor, and focused less on the sharks’ role in the general misery and loss of life. Of his 2,800-word statement submitted to a Senate inquiry in 1999, Indianapolis survivor Woody Eugene James devotes relatively little attention to the sharks:

Day two was when the sharks showed up, in fact they showed up the afternoon before but I don’t know of anybody being bit. Maybe one on the second day but we just know we’ll be picked up today. They’ve got it all organized by now, they’ll be out here pretty soon and get us, we all thought. The day wore on and the sharks were around. Come nighttime and nobody showed up. We had another night of cold, prayin’ for the sun to come up. What a long night . . . The sun finally did rise and it got warmed up again. Some of the guys been drinkin’ salt water by now, and they were goin’ bezerk. They’d tell you big stories about the Indianapolis is not sunk, it’s just right there under the surface . . . The day wore on and the sharks were around, hundreds of them. You’d hear guys scream, especially late in the afternoon. Seemed like the sharks were the worst late in the afternoon than they were during the day. Then they fed at night too. Everything would be quiet and then you’d hear somebody scream and you knew a shark had got him . . . It didn’t ever get any cooler in the daytime. In fact, Newhall asked me, he said, ‘James, do you think it’s any hotter in hell than it is here?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, Jim, but if it is, I ain’t goin’.16

Like those of the Nova Scotia and the Laconia, the 900 survivors of the Indianapolis were left far too long in the ocean, where shark attacks were only one of their problems. Without in any way trivializing the horror and the helplessness of the victims, we must remember that the open ocean is the sharks’ habitat, where they rule as apex predators feeding on whatever they find. The vibrations from explosions followed by thrashing men would have attracted sharks. The massive bleeding of the wounded would certainly have excited them. Human carcasses in the water serve as excellent appetizers. Had the crew of the Indianapolis been rescued within a reasonable period, shark predation would have been minimal.

Poster for Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film Jaws.

The shark species implicated in the Indianapolis attacks included tiger sharks, oceanic whitetips, short-fin makos and blue sharks. Of these attackers, oceanic whitetips were the most numerous and, with their large rounded dorsal fins, most easily identified. The Indianapolis casualties attributed to oceanic whitetips are estimated to be at least 80 or 90 which, combined with their many victims on the Laconia and the Nova Scotia, would make the oceanic whitetip the greatest man-eater of all sharks – not because of any fondness for human flesh, but because our wartime maritime disasters left people so vulnerable for such long periods of time.

According to mythology, the rogue shark prowls the beaches, haunts the harbours and even swims upstream in his monstrous quest for innocent people to maim and kill. Jaws uses this myth as its central sensation and conceit. In both the Benchley novel and the Spielberg film, the shark-protagonist is a white shark of monstrous dimensions that besets a popular tourist island very much like Martha’s Vineyard or Nantucket, off the coast of Massachusetts. In fact, large white sharks do make their way into these waters every summer as they follow whale and fish into the deep-water eddies off the Gulf Stream; however, no shark attacks have ever been recorded at Nantucket or Martha’s Vineyard. The precursor for the Jaws monster was not a contemporary event but a series of attacks that occurred in New Jersey in 1916. Within twelve days in July of that year, a shark or sharks mauled five swimmers, killing four and attracting the attention of millions, including President Wilson.

Before becoming president, Woodrow Wilson had been governor of New Jersey, as well as president of Princeton University, and he summered on the Jersey shore. In 1916 he was in Asbury Park, with a large contingent of reporters loitering nearby, picking up occasional dry news about trade policy or US neutrality. The first attack occurred in Beach Haven. Charles Vansant, a recent graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, was swimming about fifteen metres out, just beyond the surf line. Onlookers saw the shark rapidly approaching. Vansant was dragged beneath the surface. He was rescued but died en route to hospital.17 Five days later, on 6 July, another young man, Charles Bruder, was attacked in front of a popular hotel in Spring Lake, an opulent resort 45 miles north of Beach Haven. This was much closer to the place where Wilson was summering and the press corp was encamped. Bruder was a hotel employee and a vigorous swimmer. He was alone and about 120 metres from shore when he was attacked. The shark severed both his legs; the water was so red that witnesses at first concluded that a red canoe must have capsized and the paddlers were floundering.18 Over the following weeks these details were repeated many times in the press.

During the same week, children in New York City were dying at the rate of one per hour from a polio epidemic.19 The Battle of the Somme also began that week; on 1 July the British Army suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 deaths. Yet the American press was obsessed with ‘the man-eaters’ on the New Jersey shore. Perhaps it was the proximity of the President. Perhaps newspaper editors sensed the public’s desire to be distracted from more widespread horrors.

The third day of shark attacks was 12 July. The mouth of Matawan Creek is located on Raritan Bay, not far from New York harbour. The creek is a tidal inlet, extending about ten miles and becoming increasingly fresh-water. An eleven-year-old boy and the 24-year-old man who subsequently tried to recover his body were killed in the fresh-water section by a shark of about 2.5 metres. A second boy was subsequently badly mauled a few hundred metres downstream, but he made a full recovery. The shark was assumed to be the same one that had attacked Vansant and Bruder, and rewards were offered for the criminal. Locals of all ages patrolled Matawan Creek with shotguns at the ready. President Wilson called a cabinet meeting, at which they decided to mobilize the US Coast Guard and the revenue boats of the Treasury Department in the search of the killer shark. Fishermen landed hundreds of sharks, including many sandbar sharks, dusky sharks, bull sharks and large but harmless thresher sharks. Fishing fleets had reported an unusually large number of sharks following the schools of baitfish along the coast that year. On 14 July, in Raritan Bay, an amateur fisherman named Michael Schleisser hooked a juvenile white shark and killed it with a broken oar. The shark was only two metres long (small for a great white) but its stomach contained human remains. Since no other shark attacks occurred, Mr Schleisser’s shark was assumed to be the Matawan shark as well as the attacker at Beach Haven and Spring Lake – the ‘rogue shark’ that had been hunting people along that stretch of coast.

|

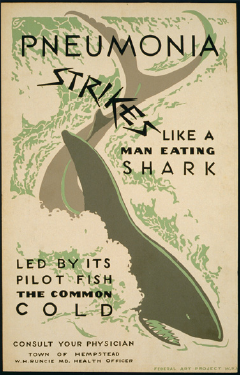

‘Pneumonia strikes like a man eating shark led by its pilot fish the common cold: Consult your physician’. WPA poster, 1937. |

Unfortunately for the species concerned, no attempts were made to compare the remains retrieved from the shark with the victims’ wounds. The shark’s capture in proximity to the mouth of Raritan Creek was evidence enough to conclude that, having savagely attacked two swimmers along the coast, the same shark had penetrated inland to seek out other unsuspecting victims. The newspapers equipped each of these victims with a sympathetic or heroic life story. In fact, the behaviour of the shark in Matawan Creek strongly indicates that it was a bull shark, not a white shark. Bull sharks often pass between salt water and fresh water, whereas white sharks lack the biological mechanisms to breathe in fresh water. Bull sharks also like to hang nearly motionless in muddy holes, while white sharks must swim continuously to stay alive. The point here is not to rescue the reputation of the great white shark, nor to damage that of the bull shark, but to recognize that myth-making in this famous set of incidents was based not on science but on a mass eagerness to believe. The rogue shark myth, with the tragedy of four manly young Americans killed and a culprit shark caught and blame assigned, offers a dramatic completion and catharsis. But beyond the ways that we may transfer real fears of world wars and epidemics of infantile paralysis onto fishier notions such as sharks as serial killers, there exists the question of why we like to scare ourselves. Pacific Island cultures, often labelled as ‘primitive’, don’t drive themselves to distraction by magnifying the dangers of shark attack or volcanic eruptions, or by dramatizing the gruesome details of shark bite or immolation by lava. Fright entertainment, the creating and inflaming of phobias, is a Western cultural norm, not only because our circumstances allow us to choose whether to go in the water or live in the shadow of an active volcano, but also because we’re haunted by visions of hell and – at least since Freud – fascinated by our own inner recesses and dark depths.