Black hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii), Mexican hawthorn (Crataegus mexicana), and others

Hawthorns have long been used as medicinal plants (need help lowering your cholesterol level?), a vitamin-packed food, strong wood for farm implements, and so much more. Even their thorns are useful! There are more than 100 varieties of hawthorn trees in North America, in part because all the true species readily hybridize with each other, creating many varieties or subspecies with unique traits. The trees can be either small or large, with white to pinkish flowers and red fruits. These fruits — sometimes called berries or haws — look similar to rose hips (indeed, roses are in the same family).

Several parts of the hawthorn are edible: the leaves are eaten as a salad herb, and the flowers are edible, too. Haws can be prepared in a number of ways. Many tribal groups, including the Chippewa, dried the vitamin-rich hawthorn haws into small cakes to be stored for winter; they also stewed the fresh or dried haws. Early settlers made wine from them, which was either drunk for pleasure or dispensed as a heart-tonic medicine.

Even today the haws are preserved as tasty jams and jellies or delicious herbal honey. In Mexico there is a tradition of cooking up the haws with other kinds of fruits, and the haws are also made into a Christmas celebration punch.

Hawthorn jelly is one delicious way to take your heart tonic.

Because of their tolerance for arid climates and lack of water, hawthorn trees are often recommended for landscapes where water must be conserved. They provide habitat for many kinds of wildlife — especially birds like waxwings and thrushes, which eat the berries.

In addition to treating physical heart conditions, hawthorn has a long history of being used for emotional well-being. The Celts believed that hawthorn would heal a broken heart. In ancient Greece, wedding processions carried hawthorn branches to symbolize hope. And in the early 1930s, Edward Bach, a medical doctor and surgeon in England, developed flower essences — a natural preparation made by steeping flowers in water and preserving them with brandy — to treat symptoms of emotional imbalance. Hawthorn flowers, in particular, were indicated for emotions of the heart.

Wood from hawthorn trees is very hard, heavy, and super strong. It’s typically too heavy to be used in construction or for furniture, but farmers use it for fence posts, for tool handles, and to make farming and tractor implements. These last and hold up to serious farm work.

Because of its strong wood and wicked thorns, hawthorn is often used in Europe for laying hedges to contain livestock.

Hawthorn trees have long and wicked thorns, which can actually be put to good use! The First Nations and early settlers of British Columbia used the thorns of black hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii) to lance boils so that they could drain and heal. The tribes in this group, including the Sekani and the Oweekeno peoples, also used the thorns to pierce their ears.

The Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe women used the thorns as awls in their sewing, especially when they were working with buckskin and sinew (the material used for lacing together the leather).

First Nations tribal fishermen in British Columbia carved hooks from the thorns and used them as the tines in rakes used to catch herring.

Crataegus has its roots in the Greek word “kratos,” which means strength.

Braided reeds and hawthorn thorns make an improvised fishing line.

For hundreds of years in both North America and Europe, hawthorn leaves, flowers, and haws have been well known as a heart tonic. Traditionally prepared as a tea, tincture, syrup, or honey, hawthorn was one of the earliest herbal medicines to be studied scientifically and is now available in capsules and other forms.

Hawthorn is used to help strengthen the heart and cardiovascular system, balance blood pressure, act as a mild diuretic, and support the body during congestive heart failure. The fact that it helps reduce excess fluids, which is a common challenge for those with congestive heart failure, makes this herb an especially good ally for people using it under these circumstances. Research indicates that it can lower LDL cholesterol (the bad kind), plus it is a rich source of antioxidant compounds. People using this plant for heart health should seek the guidance of a health-care professional.

Hibiscus martianus, H. grandiflorus, H. moscheutos, and others

A member of the mallow family, along with marsh mallow and hollyhock, hibiscus grows in places with plentiful moisture — often along waterways. It’s found mostly from central to eastern United States, but it can be located north to Ontario and south throughout Mexico. Hibiscus is famous for its brightly colored flowers that add a touch of the exotic to any landscape, wild or domestic.

On our farm we grow a hardy variety of hibiscus with huge, gorgeous flowers ranging from white to shades of pinks and bright red. It’s H. moscheutos ‘Galaxy’, and when it blooms, cars stop on the roadway to admire it. It’s been a seed crop for us nearly 16 years, but not without a specific challenge: it has no pollinators where we live. For the first few years, we didn’t get a seed crop, and we were puzzled. My husband, Chris, observed the flowers very carefully and didn’t see any pollinators working them. He decided to take matters into his own hands, literally.

Every morning during the bloom season, from late July to early September, Chris takes a paintbrush and carefully moves pollen around inside each flower to pollinate it. The flowers close at night and open in the morning about 9:00, so this is when Chris goes out to work his magic. Hand-pollination has allowed the plant to produce seed, and we harvest the ripe seedpods just as they are ready to split open.

Chris earned his nickname, Mr. Bumblebee, from a group of second-grade children who came to the farm to learn about seeds: how the flowers are pollinated and ripen into seed, how to clean the seed and make it ready to plant. After their lesson, they plant seeds in pots to take home. Chris always shows them how he pollinates hibiscus flowers and uses it as a lesson about the importance of pollinators. On any given day, it’s common for a school bus to drive past the farm with waving children calling out to “Mr. Bumblebee” as they pass.

All species of hibiscus flowers are edible, as long as they haven’t been treated with chemicals, such as pesticides or fertilizers. The flowers can be used in soups and salads and to decorate cakes. In Mexico they are sometimes candied and used as an edible garnish — a gourmet delicacy. Perhaps they could even be served with hibiscus tea, which in Mexico is called agua de jamaica.

In fact, hibiscus flowers are very important in the tea industry, which uses them in herbal and black tea blends for their tangy flavor and beautiful red color. They’re high in vitamin C and are a rich source of antioxidant bioflavonoids.

Candied hibiscus flowers are a delicious way to decorate cakes and pastries.

Hibiscus flowers follow the sun. They open in the morning as the sun gets higher in the sky. At dusk the flowers close for the night. If the sky is cloudy or they are planted in deep shade, the flowers will not open fully.

Just looking at the beautiful flowers is enough to make you smile and relax, which by itself may lower your blood pressure a bit. But in 2008 the USDA released a study that said 3 cups of hibiscus flower tea may lower moderately high blood pressure in adults. A good reason to enjoy a cup of hibiscus tea!

Because of its preference for growing near water, its seeds are available as a food source for waterbirds and bobwhite quail. Even though hibiscus isn’t a great nectar source for them, hummingbirds, butterflies, and moths are attracted to the colorful plants all the same. Beetles, flies, wasps, and a few kinds of native bees collect pollen from them, though honeybees don’t bother with them. The seedpods are an important food source for many kinds of moth larvae.

Women sometimes like to wear a beautiful hibiscus flower in their hair (a custom that began in Hawaii but has been embraced by many women in North America) to complement a gorgeous dress or when they are going out on a romantic date. A hibiscus flower worn pinned behind the left ear means a woman is married or in a relationship. A hibiscus flower worn behind the right ear means she is single and open to the possibility of a new relationship.

Shagbark hickory (Carya ovata), mockernut hickory (C. tomentosa), and others

As you are walking in the forest, keep your eyes open for a tall tree with shaggy bark that looks like the tree is about to shed its skin. Now search the ground near the tree for dark-shelled nuts that seem like they’ve been scored into quarters. Once that outer shell is removed, you’ll find a hard, light-colored internal nut shell that contains a delicious nut meat. This is shagbark hickory!

One of the hardest hardwoods, it grows in forest communities with cherry, oak, and ash trees. Hickory is a tree of diverse uses from lumber to food to recreational equipment. It offers its wood and nuts for many purposes, and although it can live as long as 250 years, it must be 40 years old before it will produce its first nut crop.

In a tradition that began with Native American tribes long ago and continues today, the green wood from hickory trees is used to make objects that require a bend or curve. Hickory is a strong wood that, once curved into the proper shape, will keep its strength without easily cracking or splintering. For this reason, it’s a wood of choice to weave into carrying baskets, to shape into the framework of a canoe that will later receive a skin of birch bark, or to create the graceful but effective curve of a hunter’s bow.

Hickory wood is so strong, it’s one of only a few hardwoods that are considered appropriate for the handles of tools like axes, hammers, shovels, and picks, where a strong handle is critical for accomplishing tasks safely.

When wagon trains traveled across North America in the 1800s, the spokes of their wagon wheels were often made from hickory. The durable wood was well suited to the stresses of traversing dangerous terrain in harsh weather.

The craft of making bentwood furniture began in Europe around the 1830s with Michael Thonet, but it didn’t take long for the practice to reach North America. By 1871 sales locations for the Gebrüder Thonet furniture company in Chicago and New York sold bentwood rockers, chairs, and stools shaped from green hickory wood.

Hickory wood has traditionally been used not only to make tools and furniture but also to build recreational sporting equipment like skis, fishing poles, hockey sticks, and even tennis rackets.

One of the strongest woods around, hickory was ideal for making wagon wheels to withstand the journey across the plains.

Cherokees prepare a soup called ku-nu-che to celebrate special occasions like birthdays, holidays, and family gatherings.

Hickory nuts have been and continue to be used in baked goods like pies, cakes, and cookies. They are added to breads in the same way as walnuts or pecans. They are simply delicious! And the cracked nuts have been favored as a snack food dating back to the days of early pioneers.

Because of its high BTUs — 24 per cord — hickory is wonderful firewood. It is widely used as a smoking wood for hams and bacon, and it makes high-quality charcoal, too.

Fall is the time to look for hickory nuts; if you’re out for a hike, you may even see the fallen nuts before you notice the tree itself.

The people of the Ojibwe tribe steamed the young shoots of hickory trees and inhaled the steam to relieve headaches. The Potawatomi Indians soaked a cloth in a decoction made from the tree bark and applied it to rheumatic joints as a compress to relieve achiness. Iroquois people made oil from hickory nuts, mixed it with bear fat, and spread it on their skin to repel insects.

Iroquois and Ojibwe medicine men (both pictured here in a ceremonial meeting) were known to have used hickory medicinally.

Most people are familiar with maple syrup, but less well known is hickory syrup — a smoky, sweet product the Algonquian Indians and European settlers made from hickory bark rather than the tree sap. This traditional food was almost forgotten until Joyce and Travis Miller began making hickory bark syrup (mainly from shagbark hickory trees) a few years ago, as a unique product to sell at farmers’ markets. What they thought would be a nice way to generate some extra income has become a thriving small business and has revived a traditional food item.

Following a recipe Travis developed after much experimenting, the Millers gather the bark — which the trees naturally shed — and toast it to improve the flavor. Then they extract the toasted bark by simmering it gently in water until the liquid has a nice, rich brown color and until the original volume of liquid is reduced by 25 percent or so. They then age the extract and filter it before adding turbinado, a minimally processed sugar. Next, they boil the mixture to just the right temperature of 211°F to achieve syrup. It’s bottled at 185°F, sealed, and labeled.

The Millers have built relationships with several national and historical monuments to produce syrup and label it specifically for these locations to sell in their private gift shops. They feel this is another way to help bring back awareness of this very sweet and wonderful syrup.

Horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), California buckeye (A. californica), Ohio buckeye (A. glabra), and others

Eat it or leave it? Although in passing you might confuse the nuts of horse chestnut or buckeye trees with those of true chestnut trees (Castanea species), you certainly wouldn’t want to swap them in a recipe; nuts in the Aesculus genus are widely considered to be poisonous. Even so, they have historically been used as a food source (when times were tough), and when properly processed, they have been used as a powerful medicine.

The nuts of Ohio buckeye were tied into bundles and placed in streams, where their toxic compounds would paralyze the fish in the area, causing the fish to float up to the surface of the water where they could be easily gathered up by Creek Indian fishermen.

Horse chestnut has a long history of use as a traditional herbal remedy to reduce fevers and to treat joint pain, diarrhea and dysentery, and even malaria. Today clinical studies have shown that an extraction of the key constituent, aescin, can be useful in treating vascular conditions like varicose veins, thrombosis, and hemorrhoids. Given its toxicity, though, it is a plant that should be treated with utmost respect and care, and should only be used under the careful guidance of a health-care professional.

Cherokee people carried red buckeye nuts in their pockets to bring good luck and to rid themselves of rheumatism or painful joints.

Although all species of Aesculus are poisonous (they contain glycoside compounds that can be dangerous if taken internally), these trees still have a long history of use as food and medicine. The seeds, or nuts as they are usually referred to, have been ground and leached (soaked in water) by Native Americans throughout North America to yield a starchy food that could be made into soups or small cakes. These groups felt that when the bitterness was gone, the toxins had been leached out and the nuts would be safe to eat. Horse chestnuts or buckeyes were considered a less desirable food than acorns, which would be used up first (and which also required this leaching process to be edible). Horse chestnuts were consumed only if food was scarce.

Equisetum arvense

As a child I grew up playing with horsetail — which we called snake grass — making its jointed stems into necklaces and pretending that its snakelike head was a real snake to tease my little sisters and friends. Using this plant as a toy is not new; indeed, the Plains Apache Indians made toy whistles for their children from the hollow stems. The botanical name Equisetum comes from the Latin equus (“horse”) and seta (“bristle”). Snake grass, bottlebrush, and joint grass are just a few of the other common names for horsetail.

Historically the fertile part of horsetail would be bundled together and then used to polish metals, especially pewter. Early settlers used it in the same fashion to scrub pots and pans clean. Both Native Americans and woodworkers of all kinds have used horsetail bundles as a primitive but very fine-quality sandpaper. The Ponca tribe considered it useful for smoothing the surface of their bows. Woodworkers sanding tiny detailed carvings consider it to be finer than steel wool. On one of my visits to a historic castle in Edinburgh, Scotland, some years back, there was a man restoring some wood carving in the castle chapel. I was amazed to see that he was using bundled horsetail to do a bit of sanding on his work.

Horsetail is a unique perennial plant that reproduces by spores, much like its relative the fern. It grows in two cycles. In the first cycle, the fertile part of the plant grows in early spring, producing jointed stems and what looks like a scaly snake’s head. This part releases spores to reproduce the plant. When this first cycle of the plant dies back in late spring or early summer, it is replaced by the infertile part, which is bushy along the jointed stem and resembles a horse’s tail, hence its name.

The Cheyenne people and other tribal groups that work with porcupine quills in their beadwork on moccasins and clothing and for jewelry have used horsetail to dye their porcupine quills pink. A mordant of alum is required to achieve a permanent pink fiber dye from horsetail.

Horsetail grows in moist soil, usually near streams and rivers. It prefers sandy, gravelly, or clay soils and extends roots deep into the earth some 40 feet, where it draws up minerals, especially potassium and silica, into its plant tissues. It also draws up metals like gold, copper, molybdenum, and others. This herb is known to grow on land in every part of the planet except Antarctica.

Geologists and mining engineers use horsetail as an “indicator plant,” as it often grows well in places where these types of metals, along with silver and zinc, can be found. An abundance of horsetail might warrant further testing to see if mining potential exists in a specific area.

It’s also true that if the soil upstream or near the horsetail has been seriously disturbed, as during gravel mining or after a big storm event, the plant will draw up dangerous levels of these minerals and metals. Horsetail is a medicinal plant only collected in spring and early summer months; however, if it is growing in seriously disturbed areas, it should not be used internally as a medicinal plant for humans or animals.

Dried horsetail that has been baled with hay is extremely poisonous to horses if they eat it. Horsetail contains an enzyme called thiaminase that destroys vitamin B1 in horses. If horses accidently are poisoned by horsetail in their feed, they often respond well to vitamin B1 supplementation.

Bears, however, will eat horsetail sometimes right after they wake up from winter hibernation. The plant is coarse; as it goes through their intestinal tract, it has a cleansing and laxative effect that is helpful to the bears as they prepare to begin their foraging seasons.

Horsetail dates from the Paleozoic era (about 400 million years ago), when it grew big as a tree.

Sugar maple (Acer saccharum), bigleaf maple (A. macrophyllum), and others

Here is a baker’s dozen of useful relatives! Thirteen different kinds of maple are native to North America, and all of them are useful. Of course, we all love maple syrup, but few people know that the sweet stuff we put on pancakes contains at least 20 different medicinal compounds. After your pancake breakfast, you could head outside to play baseball (with a maple-wood bat) or perhaps listen to an orchestra (playing instruments made of maple).

Broom and ax handles, garden tools, and kitchen utensils like cutting boards and rolling pins are often made from maple. The wood is hard and strong but not too heavy, so it works quite nicely for these types of tools. The Molalla tribe in Oregon used the inner bark for making rope and weaving baskets. Some Cherokee basket weavers still weave with maple inner bark and small twigs.

Furniture, both practical and decorative, is often constructed with maple lumber, which has a fine grain. Bigleaf maple is a common commercial lumber for furniture. Burl maple has a lot of burls and knots, which gives it beautiful interest for decorative furniture like coffee tables.

Long ago, tribal groups like the Interior Salish Indians made snowshoe frames and canoe paddles from maple; indeed, the Lakwungen (Lekwungen) people of Vancouver Island, along with other tribes in western regions of North America, called this “paddle tree.”

Maple has been an important resource for outdoor recreation and sports equipment. Since 1998 professional Major League Baseball bats have been turned from maple wood. Recurve archery bows, boat paddles, and raft oars are still made with maple today.

Maple wood has very good tone — another way of saying it sounds great when it’s made into musical instruments. Many kinds of string instruments, such as double basses, cellos, and violins, have sides, backs, or necks formed from maple wood. Bird’s-eye maple, which is actually sugar maple that has been growing under some kind of difficult situation such as too much shade, is a beautiful wood that is often used for string instruments. Maple wood has a crisp, resonant sound favored by drum makers; certain kinds of drum sticks are carved from maple, too. Woodwind instruments, especially bassoons and recorders, are often made with maple wood.

Several tribes like the Mohegan people brewed maple bark into a strong tea and used it to soothe a sore throat. Interestingly, various western tribes used Rocky Mountain maple bark as a poison antidote. Maple bark tea soothed sore eyes and was used as a skin wash for hives. The Chippewa tribe found the tea very beneficial to promote the healing of wounds, while the Cherokee people drank it for measles and their women used it for menstrual cramps.

Native people have used the bark and the seeds as food, too. The Iroquois people dried the bark and cooked it into a thickening gruel; sometimes they also made bread from this. Maple seeds were eaten three ways: raw, roasted, or boiled.

Maple syrup is a North American treasure and part of a long-standing tradition for both indigenous people and European settlers. It’s made by collecting and boiling sap from any of a number of different kinds of maple trees, but typically from sugar or red maple trees. Bigleaf maple is said to have the most flavorful sap but with a lower sugar content, which just means it takes a lot more sap to make an equal amount of syrup compared to other kinds of maple trees.

Maple syrup is more than just a tasty sweetener, though. The University of Rhode Island released a report in 2010 that stated maple syrup also offers medicinal benefits because of the more than 20 different medicinal compounds it contains. These have antioxidant, antibacterial, antidiabetic, and anticancer properties. In addition, maple syrup contains a wealth of minerals from calcium to zinc. So, maple syrup is not only delicious, but it can be good for you.

Honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), screwbean (P. pubescens), and others

A native of the southwestern regions of the United States and northern Mexico, mesquite has been a much-relied-on source of food, building material, and livestock forage for the people of these regions. It’s a member of the legume family, and its seedpods really do resemble large beans. Screwbean mesquite pods twist into a corkscrew, hence the name. All mesquite trees, regardless of the species, have wicked thorns on their branches!

Honey mesquite is very sweet and is sometimes chewed as a sweet treat. The resin produces a dark brown to black dye, which is used for textiles and as hair dye. Traditionally, Papago (Tohono O’odham) Indians in southern Arizona mixed the resin with the mineral hematite, which creates a red paint used to decorate pottery.

The resin has also been made into an adhesive, and it shows potential to be used like gum arabic — a resin from the acacia tree that is used in foods and industrial products.

As a young herb student attending an ethnobiology conference in 1986, I got a wonderful introduction to this plant in the form of a delicious sweet drink. The drink had been made from coarsely ground pods soaked in water. I’ve been enchanted with the plant ever since. I now use mesquite flour to make corn bread and cookies, and I keep a potted mesquite tree (alas, the tree would not be hardy outside here in Colorado).

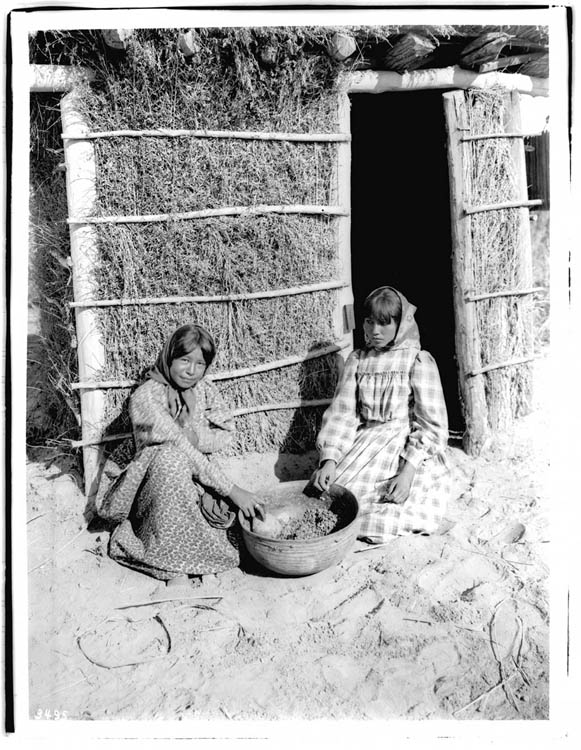

Two young Chemehuevi Indian girls make a nourishing drink from mesquite beans.

Mesquite bean pods are very high in sugar (36 percent sucrose), contain 13 percent protein, and are rich in minerals like calcium and iron. They are twice as sweet as sugar beets and sugarcane, our normal sources of commercial sugar. Since the pods are so high in sugar, they have been used, like corn, to produce alcohol.

The bean pods can be eaten raw or cooked, usually with the seeds removed before the pod is prepared for use. Green pods, when boiled, yield a nutritious sweet syrup. Dried pods are most often ground into meal and used to replace a portion of the flour called for in recipes for tortillas, cakes, breads, and the like. Gary Paul Nabhan, an internationally known ethnobotanist, has been working for many years, along with groups like Native Seeds/SEARCH, to restore mesquite flour’s popularity in the Southwest and northern Mexico, where it once was a prominent staple food.

Mesquite pods are picked in late summer or fall. They store well for winter food, but if they are to be stored for long, they should be roasted first to kill any bruchid beetle larvae that may have made themselves at home inside the pods. (Mesquite trees are forage for these beetles.)

Each tree produces pods with varying amounts of sweet to bitter bean pods. When a particular tree is found to produce bitter pods, harvesters avoid picking from that tree during the following harvest season.

Sweet, nutty-tasting mesquite meal is mixed with flour to make tortillas, breads, and cakes.

This tree’s wood is invaluable, too. The lumber is appropriate for everything from fencing to tool handles and gunstocks to intricate wood carvings. Its reddish-brown color is quite attractive, and because of this rich color, it’s quite often incorporated in parquet floor tiles. Because the wood is very water resistant, in parts of Mexico mesquite is a preferred material for building the framework of fishing boats.

As firewood, it’s excellent. At 8,653 BTUs (similar to medium-grade coal), it burns very slowly. Potters who use wood-fired kilns like mesquite wood as kiln fuel because it burns slowly; the kiln doesn’t need to be stoked as often. Mesquite charcoal is also highly prized for barbecuing for the same reason (and for its flavor).

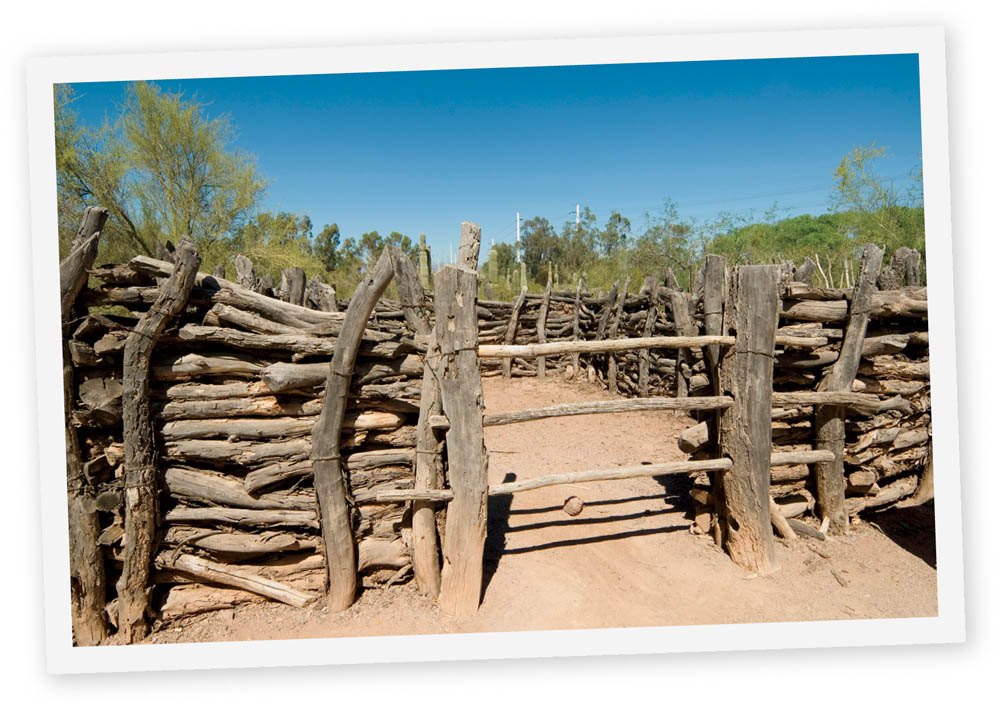

Strong, durable mesquite wood is perfect for building fences and corrals.

Mesquite trees have an important history of use as livestock forage, but one of the unintended consequences has been that the seeds are often dispersed throughout a wide area as the cattle who browse them move about. In some places, honey mesquite trees are now on the verge of becoming invasive. Once established, the tree is difficult to eradicate: its roots can grow 200 feet down and 45 feet across, making digging an impractical management tool. Mesquite also resprouts from its roots, sending up shoots when the main trunk is cut down.

The trees, like all legumes, do fix nitrogen in the soil, which improves the soil’s porosity and organic matter. This helps other plants growing in community with mesquite, so this is a positive contribution the tree makes to its ecosystem. However, it is opportunistic and will take advantage of water resources in extremely arid climates. As honey mesquite populations expand beyond their normal range, they’re contributing to water supply challenges, which has earned the tree the name of “water hog.”

Theobroma cacao and others

Few of us would disagree that chocolate, which comes from the seeds of the cacao tree, is truly delicious and an important food in our culture. But it has a long history — medicinally, ceremonially, and as food — that goes beyond today’s after-dinner treat or box of Valentine’s Day candy.

In 1753 Carl Linnaeus, the famous Swedish botanist, gave cacao its Latin genus name, Theobroma, which means “food of the gods.” More than 2,000 years ago, the Aztec people named it xocolatl, which means “bitter water.”

Cacao trees are native to Mexico, Central America, and northern South America, where they often grow along riverbanks or on plantations. Each tree produces large pods that hold 30 to 40 seeds. The seeds are harvested, fermented, and then dried in the sun until they turn brownish red. At this point they actually begin to resemble beans. This process has been followed for centuries, first by the Olmec people of Mexico and Guatemala, who started the very first plantations to produce cacao beans in 400 BCE.

Roasting the cacao beans after they’ve fermented helps release their chocolatey flavor.

In Mexico, and around the world, cacao beans are processed into cocoa powder and cocoa butter, which are then used to make sweet treats. Mexican chocolate is quite different from European-style chocolate. In Mexico, chocolate is consumed largely as a beverage, but it’s also enjoyed as candy. Traditionally, Mexican candy is coarsely ground and shaped into round disks, whereas European-style chocolate is smooth in texture and shaped into rectangular bars.

Studies are confirming the medicinal benefits of eating dark chocolate in the amounts of 46 to 105 grams a day.

To the Aztec and Mayan peoples, cacao beans were so important they were used as currency. For example, a list from Tlaxcala, Mexico, in 1545 shows equivalent values for cacao beans as currency: 100 cacao beans would buy “one good turkey hen,” while 1 cacao bean would get you a tomato or an avocado. Typically, only royalty or wealthy warriors could afford cacao beans, and they used them to prepare chocolate sweets or consumed it as drinking chocolate. Both were made using cocoa powder, then flavored with vanilla, chile peppers, honey, and aromatic herbs.

Christopher Columbus learned about chocolate in Mexico in 1502. By the 1520s Spanish explorers had brought cacao beans back to Europe, where it became very popular for the wealthy to sip cups of hot chocolate.

Cacao beans have also played an important part in ceremonial rituals of religion, engagement, and marriage throughout Mexico and the Latin American countries. In the Mayan tradition, chocolate was part of the ceremonial ritual blessing of a baby. Cacao seeds, along with flowers, would be ground up and mixed with water. Then the baby’s head, feet, hands, and face would be anointed with the mixture. Today’s wedding traditions in small towns or villages in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, call for guests to be given a large bowl of hot chocolate (always made with water rather than milk) along with a large piece of bread called pan de yema to enjoy before the wedding banquet begins.

A performance depicts a traditional celebration of the Mayan god of cacao, Ek Chuah.

Archaeologists have discovered Mayan paintings and carvings from 250 CE that show the Mayan people drinking cacoa in religious rituals, such as blessing ceremonies for newborn babies and marriage ceremonies. They also felt it was a good medicine plant to reduce fevers and treat a wide range of ailments, to quench thirst, and to improve energy.

Cacao trees are having a hard time; they are susceptible to fungal infections like the monilia fungus (a type of powdery mildew), which is spread by insects and is attacking trees in several Mexican states. The result is that fewer and fewer Mexican cacao trees are now being grown.

The painting on this Mayan vase depicts a medicine man and a cacao tree.

A traditional practice in Mexico, Ecuador, and Colombia is to apply a cacao poultice to treat wounds and snakebites. It contains at least 26 different anti-inflammatory constituents that help reduce swelling and act as an astringent. Additionally, the plant contains five known vasoconstrictor compounds that help narrow blood vessels, slowing the spread of poison from a snakebite. There are also antiseptic and antibiotic properties in the beans, which can be useful in wound healing. (That said, cacao is not a substitute for medical treatment if you suffer from a snakebite.)

Studies are confirming the medicinal benefits of eating dark chocolate in the amounts of 46 to 105 grams a day. Dark chocolate can have a positive effect on lowering blood pressure and may decrease some risks of heart disease. Although most of us don’t really need a good excuse to eat our chocolate, perhaps these are reasons enough. It should be noted, though, that milk chocolate is not very useful as a health-supportive food because it is too diluted by other ingredients like sugar and cream.

In the early 2000s, Alex Whitmore became interested in the traditional manner of producing Mexican chocolate. He traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico, where he studied with Mexican chocolate makers, learning how to grind cacao beans minimally with great round grinding stones and how to prepare a Mexican style of chocolate candy. In 2006 he founded the company Taza Chocolate.

One of the company’s tenets is a strong ethical policy about how chocolate should be sourced and processed. Taza doesn’t buy raw materials through brokers; instead, employees work directly with cocoa producers and producer groups (co-ops and fair trade organizations). Each year they visit the growers and producer groups to keep relationships strong and to maintain strict quality standards. All of their growers are 100 percent certified organic, as is the company’s processing facility, which is also certified fair trade. As a matter of principle, Taza Chocolate pays above fair trade prices for cacao beans, and everything done by the company is third-party verified so that consumers know they’ve met all these standards.

Here’s how the process works. Growers harvest and ferment the cacao beans by piling them in sacks or boxes. Once the fermentation process is complete, the beans are dried and sent to Taza Chocolate’s processing facility in Massachusetts. On arrival they are ground in the milling room, using grinding stones that have been made in the traditional way. Because the beans are very sensitive to temperature and fluctuations can cause changes in flavor and texture, it’s important that the milling room be maintained at 88°F during the grinding process. This keeps the chocolate fluid and yields the best-tasting product. After grinding, other ingredients are added, and the chocolate is shaped into disks and wrapped in paper. Then it’s ready for sale.

Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), showy milkweed (A. speciosa), butterfly milkweed/pleurisy root (A. tuberosa), and others

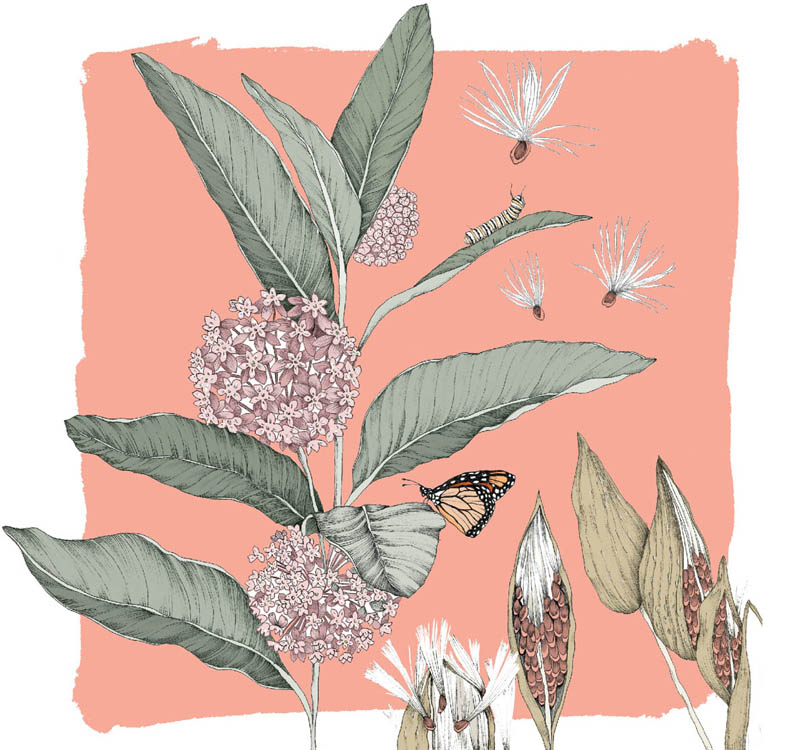

Probably the best-known fact about milkweed is that it’s a host plant for butterflies like the monarch. In reality, although the plants are food for several different species of butterflies (not to mention a source of nectar for moths and hummingbirds), they are the sole food source for monarch butterfly larvae. Growing any of the milkweed species in your garden will attract a wonderful array of these creatures. Besides being a great wildlife plant, milkweeds have been used by humans as food and medicine, as textile material, and even for industrial purposes.

Native people, early settlers, and modern foragers alike have eaten milkweed as a cooked vegetable. Nearly every part is edible, but each must be harvested at just the right time. Young, tender shoots in early spring; unopened flower buds in midsummer; firm, green seedpods in late summer — all can be eaten if they are boiled in multiple changes of water. Cook the unopened flower buds very well in sugar water until it thickens into a syrup, then strain out the cooked flowers and drizzle the milkweed flower syrup lightly over a dish of vanilla ice cream. If the plants are eaten raw or are too old or picked at the wrong time, however, they may cause nausea or vomiting.

You wouldn’t want to eat the fluff of a mature pod, but young pods and flowers are actually quite tasty and nutritious.

Ironically (given its reputation as a host plant for pollinators), milkweed can also be used as a pesticide! Its seeds contain cardenolides, a compound that kills nematodes and armyworms. These are destructive pests for crops such as potatoes, soybeans, alfalfa, tomatoes, and corn. In field studies, turning milkweed seed meal into the soil resulted in 97 percent of the pests being killed, and with greater safety for humans and less negative environmental impact to wildlife, soil, and water than when conventional pesticides are employed.

Seed floss from milkweed proved to be a valuable tool during the twentieth century. During World War II, the Japanese cut off access to Java, so the U.S. Navy needed to find an alternative to Javanese kapok (a plant tree cultivated for its buoyant seed floss) to fill its life jackets. They found a homegrown solution in milkweed; its seed floss is hollow and coated with a natural plant wax, which makes it waterproof and allows it to float. The federal government paid American schoolchildren 15 cents for every onion bag of unopened milkweed seedpods they collected. Each bag held between 600 to 800 pods, and two bags filled with the pods supplied enough seed floss to fill one life jacket. The navy made 1.2 million life jackets from milkweed seed floss during this time.

Interestingly, even though it repels water, milkweed floss actually absorbs oil. Because of this helpful trait, the seed floss is currently used to make floating kits that help clean up man-made oil spills (see the profile, Fluff with a Function, below).

Interestingly, even though it repels water, milkweed floss actually absorbs oil. Because of this helpful trait, the seed floss is currently used to make floating kits that help clean up man-made oil spills.

Milkweed has medicinal uses, too! A number of Native tribes have used the latex juice from the roots, plant tops, and stem for medicinal purposes. The Miwok people used the latex to remove warts. The Cheyenne made a decoction of the dried plant tops and used it as an eyewash to heal snow blindness. Cherokee, Delaware, and Mohegan peoples used pleurisy root, also called butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), made into a cough remedy. Today herbalists still use it for pleurisy, an inflammation in the lining around the lungs. The southwestern milkweed named immortal (Asclepias asperula), also called antelope horns because of the unique shape of the flowers, has traditionally been used for heart conditions.

Beyond its uses by indigenous people, milkweed was at one time a medicine that pharmacists prepared. Milkweeds have been prepared as tinctures and used as emetics to induce vomiting in the case of poisoning. From 1820 to 1905 Asclepias tuberosa was listed in the United States Pharmacopeia, and from 1906 to 1936 it was included in the National Formulary as an official botanical drug to treat the condition of pleurisy.

In Canada there is a company doing incredible work with milkweed in order to improve the earth’s environment, pay farmers a living wage, and help butterflies survive. The company, Encore3 Industries, was begun by three engineers who wanted to make a difference. And they’re succeeding!

Oil-spill cleanup kits. Using the oil-absorbent seed floss from the milkweed plant, they are manufacturing kits that serve as an alternative to the synthetic polypropylene currently used to absorb oil spills. Each kit can hold five times more oil than its polypropylene counterpart, and one method of disposing of the used kits is as a possible energy source for incinerators and power plants. Canadian national parks are even employing the kits as part of their emergency response programs, and the petroleum industry has expressed interest as well.

Insulation. In addition to the oil-spill kits, Encore3 is using milkweed floss to make insulated winter garments and bedding like pillows and comforters. The floss has very good insulation properties and is hypoallergenic, unlike goose down.

Biofuel and nutrient-rich oil. A by-product of the floss products is the seed and seedpods. The seedpods can be pressed into pellets for use as a biofuel for furnaces and woodstoves. The seed itself is expeller pressed into nutritious oil, rich in omega-7 fatty acids and vitamin E. It has great antioxidant properties and makes an excellent skin moisturizer.

Opportunities for farmers. Part of Encore3 Industries’ mission is to provide a way for farmers to earn a living wage. Milkweed is a perennial crop that needs to be replanted only every 10 years, grows very well with no added pesticides or fertilizers, and is an appropriate crop for arid climates where water resources are challenging. Farmers can earn as much from this crop, with fewer expenses, as they can from other grain or hay crops. And working with Encore3 gives them a stable market for the crop.

Monarch habitat. One of the best parts to this story is that milkweed crops are being grown all along the migratory routes of monarch butterflies, providing habitat and food for this threatened pollinator. The company is working with farmers along this migratory route to grow milkweed in Canada, through the United States, and into northern Mexico.

All milkweed species contain cardiac glycosides — powerful compounds that have medicinal benefits for heart health if taken correctly and with great care, but which can be toxic to humans and animals if used improperly. As with any powerful medicinal herb, they should be administered only under the careful guidance of an herbalist or other health-care professional experienced with these plants.

These same compounds offer protection to monarch and other butterfly caterpillars. When the insects feed on the plant foliage, they absorb the compounds into their bodies. This makes them taste terrible to would-be predators; over time the predators learn not to eat caterpillars from milkweed plants.

Urtica dioica

How does a plant with such incredibly bad manners that it “stings” people become such a useful plant? The stinging nettles plant is a delicious food, an amazing whole-body medicinal herb, a great textile plant, even a super compost activator. It’s almost more appropriate to ask what nettles can’t do!

I have a patch of nettles planted in my garden where they are easy to harvest, but this is a perennial herb that grows wild throughout most of the United States and across Canada. Our species of stinging nettles, along with other species, grow around the world, too, but U. dioica is the only species in North America.

Have you ever walked into a patch of stinging nettles and felt that burning, stinging, sometimes blistering sensation and wondered what really caused it? The aerial (aboveground) parts of nettles — the stem, leaves, even the flowers and seed heads — are covered with tiny hairs. These hairs have oil glands that produce a compound called formic acid. If we brush up against the plant or handle it without protective gloves, the formic acid oil will get on our skin, causing burning and blistering of the skin mucosa. This painful reaction to formic acid will continue for a while, sometimes about an hour, sometimes as long as a day, and then it disappears.

The oil is present only on the living or freshly gathered plant material, however. When stinging nettles are harvested and either dried or cooked in some fashion, the formic acid oil evaporates and is no longer a problem.

If you find yourself in an encounter with nettles (left), chances are the antidote is nearby. Crush some plantain leaves (right) and apply them to your skin to ease the sting.

All the aboveground parts of the nettles can and have been used for food. They are very nutritious: a 1-cup serving of nettles supplies 428 milligrams of calcium, nearly 51 milligrams of magnesium, 1,789 International Units of vitamin A, and more than 2 grams of protein. This has been a well-utilized food for many Native Americans, including the Iroquois, Mohegan, and Makah tribes, which all cooked nettles as a vegetable. I include nettles in soups and casseroles and marinate them in vinegar and oil. Basically, you can prepare nettles any way you would spinach, but don’t try eating it raw as a salad ingredient or on sandwiches, as that would be quite the unpleasant experience!

Nettle stems have long fibers, which have been used to make cloth for at least 2,000 years. These fibers are also twisted together to make string or rope. The Cherokee people used this cordage as bowstrings, while the Lakotas and the Hesquiahts wove it into fishing nets and other practical objects. Colonists in the late 1700s wove nettle fibers, combined with buffalo wool, to make durable and warm clothing.

The fibers can be pounded into a pulp and then screened into good-quality handmade paper; depending on the season in which the nettles are harvested, the resulting paper will be different colors. For example, nettles harvested in spring when they are vibrant green in color will yield a green paper, but nettle stalks harvested in fall or after winter will result in a brownish paper.

If you brew the leaves into a strong decoction and use it as a dye bath, it will give you a permanent green color. The roots can be boiled to give a yellow color, but to do this, a mordant of alum is necessary.

Nettle fibers can be twisted together to make string.

The Makah tribe, in the northwestern point of Washington, would rub fresh nettles on the bodies of whale hunters to make them strong. They also rubbed the fishing lines with fresh nettle leaves, which turned the lines green, and which they believed was good medicine for a successful fishing trip.

The Makah Indians believed that nettles brought them strength and good luck in fishing.

Nettle leaf is juiced and then used as a substitute for rennet to curdle milk in the process of making cheese.

Like milkweed and other native plants, nettles are an important plant to ensure the survival of several kinds of pollinators, especially those that rely on nettles as their sole food source. The tortoiseshell butterfly, the red admiral butterfly, and the mouse moth caterpillar, for example, will only feed on nettle leaves.

A nettle tonic is strong but gentle in action. It’s what herbalists call a whole-body tonic, because it supports the functions and health of every body system. It’s been used in many ways, from encouraging good digestion to relieving allergies through its antihistamine actions. It finds its way into remedies for respiratory and skin conditions and to nourish the blood. Mostly the aerial parts are used, but a tea or tincture made from the roots and taken internally can support men’s prostate health.

Indigenous people have used nettles as medicine for centuries. The Hesquiaht and the Miwok peoples used the plant to relieve muscle and joint pain — sometimes by whipping stems of fresh nettles over the affected body areas. The formic acid contacting the skin caused a temporary burning and blistering, but it also created a rush of circulation to those parts. This improved circulation in the muscles and joints gave some lasting pain relief for conditions like arthritis. Cherokee people prepared a tea from nettles and drank it as a stomach tonic. The Cree Indians considered nettles an important women’s herb during childbirth.

Cree Tribe member

Nettle aerial parts are good for nourishing soil because they are high in nitrogen. The leaves are sometimes added to compost piles to make the composting process more productive. A compost activator tea can be prepared by soaking 12 cups of fresh leafy parts for 1 to 3 weeks in a bucket filled with water, then straining out the plant material from the resulting “tea brew” and applying that liquid to either a compost pile or straight into the garden as an organic fertilizer. Studies by several horticulture and agriculture groups show nettle “tea” is a natural insect pest repellent when applied as a foliar spray, at the same time benefiting the plants as a source of nutrition and making plants more resistant to future pest attacks.

Mentha canadensis (also known as M. arvensis var. canadensis)

Mint is ubiquitous in our lives, from mint tea to chewing gum to bars of soap. As familiar as we are with spearmint or peppermint, most people have never heard of our native species, North American mint (in the Southwest where I live, we call it poleo mint). It’s the only truly native Mentha species in the United States. It has a strong flavor and scent like peppermint, with a hint of pennyroyal in the aroma. It’s also smaller and more delicate than garden-variety mints. Other common names for this plant are American wild mint, Indian mint, brook mint, and corn mint.

Native mint is a traditional herbal remedy in the places where it naturally grows. Like all mints, it has strong antispasmodic (relieves muscle cramping) and antiseptic properties. It finds use as a nonaddictive stimulant (it doesn’t contain opiate alkaloids, which are very habit forming) and is helpful as a decongestant steam to relieve respiratory congestion and as a tea to reduce fevers. Native tribes across the continent used it to treat hiccups, toothaches, headaches, and bad breath. Early settler mothers offered a weak mint tea to their babies to relieve colic.

Although this mint attracts native pollinator bees, it actually repels other insects such as gnats and mosquitoes. For this reason it’s a great herb to incorporate in an insect-repellent spray or liniment. It also repels mice and other small rodents and was historically used as a strewing herb spread on the floors of homes, barns, and granaries to make the space uninviting for such unwanted creatures. Because mint masks the scent of humans, it has historically been used by hunters and trappers, too.

Not every creature dislikes the smell of native mint, however. Wildlife biologists doing their work to reintroduce the lynx into the wild sometimes use this mint as bait in live traps because its high levels of volatile oils give it a strong fragrance. Researchers who periodically monitor the health of large wild cats sometimes use it as bait for bobcats and mountain lions, too.

Researchers use mint to attract and capture large wild cats for study.

Just as with other mints, native mint is wonderful for cooking. It is strong, though, so use it sparingly at first! Experiment a little and see how much you like. It makes a very nice jelly condiment for lamb dishes, a delicious addition to green or fruit salads, and a delightful cup of after-dinner tea. Make a refreshing sun tea from the leaves to serve iced on hot days and you’ll feel refreshed.

Early settler mothers offered a weak mint tea to their babies to relieve colic.

Canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis), black oak (Q. velutina), gambel oak (Q. gambelii), bur oak (Q. macrocarpa), and others

Oak trees are abundant throughout the United States and Mexico, where their acorns have long been valued as an important indigenous food source. The wood was a mainstay in the shipbuilding industry; trees were also debarked for leather tanning, cut down for making charcoal and for barrels to age whiskey, and replanted to restore habitat after wildfires.

Oak wood has long been used to make barrels for aging wine, brandy, and whiskey — both in North America and in Europe. Oak affects the flavor and the color of these liquors, and even their aromas, giving them a signature “oakiness.” This is due to the tannins and lactones in the wood, which impart several attributes over time, including fruity, toasted, sometimes vanilla-like aromas and flavors, and adding the golden-brownish color. White oak (Q. alba), sometimes called American oak, is usually chosen to age whiskey.

The wood is also used to smoke cheeses, fish, and meat, imparting a distinct, hearty flavor. Smoking food not only contributes to the flavor and aroma but also helps preserve the food in some cases, making it last longer.

Oak barrels give whiskey and wine their signature “oaky” aroma.

Oak wood is quite dense and hard and, because of its high tannins level, less susceptible to decay from insect or fungal damage. Because of that, it’s an ideal long-lasting lumber for construction, hardwood flooring, furniture, tool handles, fence posts, and any number of other applications that require strength and durability. Much like hickory, oak was used to make the spokes of wheels on covered wagons because it would hold up to the rugged abuse of the trail.

Wherever oak trees have grown in North America, their acorns have been an important staple food for Native American people. At one point acorns provided up to 45 percent of the diet of California tribes, which ground acorns into flour for cakes and breads or gruel. Before the acorns were safe to eat, however, they had to be leached to remove the large amounts of tannins they contain.

The entire oak tree is highly tannic — an attribute that makes the wood resist decay but also means the acorns are toxic to humans and many types of livestock, including cattle, horses, goats, and sheep. (Interestingly, pigs are not affected by tannins and are thus sometimes raised almost solely on acorns.) The tannins in acorns would cause liver damage if they were not leached out.

The leaching process turns an acorn that could be poisonous into a nutritious food. After acorns were knocked from the trees with sticks, the indigenous practice was to dry them and remove the shell, leaving only the nut meat, which was pounded into coarse acorn meal. The meal was then soaked in water, either by placing it in a bag or tightly woven basket in a gentle stream current or by soaking it in hot water and changing the water repeatedly (a minimum of 10 times). Once acorn meal was leached, it was transformed from bitter and inedible to somewhat sweet and very tasty.

Early settlers also used acorns as flour, and they roasted the leached nuts to be used as a coffee substitute.

Acorns were an important food source for native groups.

The same tannins that make acorns taste bitter are helpful for tanning leather. Bark from several oak species — including black oak (Quercus velutina), red oak (Q. rubra), and white oak (Q. alba) — is used for tanning because it contains high levels of tannins (from 6 to 30 percent). The hides are prepared to fully absorb the tanning solution through several processing steps that include removing flesh, fat, and hair; then curing with salt; then washing with water. Finally the hides are stretched over frames that are immersed in a strong oak tannin extract, which will combine with the proteins in the animal hide and cause them to become finished leather.

North America has the greatest diversity of oak species in the world, with several species native to Mexico and more than 90 species native to the United States. It’s a tree that readily hybridizes, which means there’s an unknown number of varieties of hybridized oaks in addition to the true species. It’s no surprise, then, that in 2004 the U.S. Congress passed legislation to make the oak the national tree.

And the wind said may you be as strong as the oak, yet flexible as the birch, may you stand tall as the redwood, live gracefully as the willow, and may you always bear fruit all your days on this earth.

— Native American prayer

For more than 300 years, huge oak tree forests have been cleared in Mexico — and the result has been a permanent change in the landscape. In the 1700s the trees were harvested and sent to Spain as timber for shipbuilding. Later they were cut down to make way for coffee tree plantations and to open land for cattle grazing. Still more trees have been harvested as fuel wood and for making charcoal. Because oaks are not fast-growing trees, especially in arid climates where they often grow, once the oak forests were cleared, the climate was altered enough to become a desert.

Oaks in the United States are increasingly threatened by a number of problems, some of which may be attributable to climate change. Longer drought cycles have stressed the trees, as has fire suppression/mitigation by humans, and the end result is oak trees vulnerable to pest problems like scarlet oak sawfly and several kinds of beetles and borers. Fungal diseases like sudden oak death on the West Coast and oak wilt in the eastern United States have infected and killed thousands of trees since the mid-1990s.

While oaks face some survival challenges, they are still great conservation trees — that is, trees that are planted en masse for habitat restoration following wildfires, mudslides, and floods. In the Southwest, gamble oak is considered an important plant for protecting watersheds from erosion and helping to improve water quality in those ecosystems. Bur oak is used as windbreaks, living snow fences, and shelterbelts around farm fields and along roadways in Montana and Wyoming, where intense wind and blowing snow can be a huge problem. These windbreaks also offer much-needed food and habitat for many kinds of wildlife, including black bears, elk, moose, small mammals, and many types of birds.

Mexican panic grass (Panicum hirticaule), Sonoran Desert panic grass (P. sonorum), switchgrass (P. virgatum), and coastal panic grass (P. amarulum)

Here’s a grass of many uses! Panic grass takes its name from the Latin word panicum, which means “ear of millet,” and indeed the seeds are a nutritious food similar to the grain millet. Panic grass has been used as a grain, as a material to build and heat homes, as a bioenergy plant, and as a carbon dioxide sequestration plant to mitigate climate change. It has value for ecological restoration work, and it will even support a mushroom crop.

This long-lived perennial native grass grows well in marginal soil and doesn’t use a lot of water. There are species native to the U.S. Southwest and Mexico, and other tallgrass prairie species occur throughout the middle of North America from Canada down to the border with Mexico.

Switchgrass shows great promise as a raw material for producing ethanol and butanol. Corn has been the crop typically grown to produce ethanol, but it requires good soil and lots of chemical fertilizer, pesticides, and herbicides, and as an annual crop it must be planted each year. Switchgrass — a native of the tallgrass prairie — is drought tolerant, isn’t fazed by temperature extremes, and doesn’t require heavy fertilization. A planting can last 10 years or more, and it self-seeds abundantly. As a bonus, switchgrass and other panic grass species are great for sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (meaning the plant absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and holds it within the plant tissues so that it cannot be released back into the atmosphere), so they are good tools for addressing climate change. Typically, large, long-lived trees like cottonwoods or oaks are used for this purpose, but switchgrass has found favor because it is easy and inexpensive to establish over a short period of time and will live for a decade or more with little care required, growing well in diverse weather of extreme temperatures and low water.

Switchgrass roots can grow 6 feet deep in the ground, making it an ideal plant for sequestering carbon in the soil.

Not only can you build a house with grass, you can heat it, too. Panic grass straw is baled and then used to construct the walls of straw bale homes. The grass can also be compressed into pellets and used in pellet stoves as a renewable heating source.

Panic grass produces a lot of seed, which has made it a valuable grain for tribes in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The Cocopah Indians ground the seeds into flour and then used it to bake their staple bread. Yuma people and other groups parch the seeds and then grind them into flour. In Sonora, Mexico, it continues to be cultivated as a food and livestock crop.

The dried grass is sometimes used as a growing medium to cultivate oyster mushrooms. The panic grass is harvested, then chopped, pasteurized, and mixed with 1 percent ground limestone. Then it’s inoculated with mushroom spores, and a delayed-release fertilizer is added. Panic grass harvested in winter for use as a mushroom-growing medium produced more mushrooms than when the grass was green and harvested in summer.

Ranchers plant panic grass as a perennial hay crop for livestock. One planting will grow without a lot of water or fertilizer for 10 years or more. In the wild, the grass is an important food for many types of wildlife, including wild turkey, quail, and pheasants, while providing cover protection for ground-nesting birds. Songbirds feed on its small seeds.

Dried panic grass is sometimes used as a substrate for growing mushrooms.

All species of panic grass are being used for reclamation of lands that have been damaged by mining, situations where soil highly contaminated by heavy metals or other toxins makes it difficult for other types of plants to grow and thrive. Panic grass is used to revegetate dikes and dams around ponds and reservoirs, and to stabilize soil disturbed by construction. The grass’s extensive and deep root structures are superb at stabilizing coastal sand dunes and land that’s been eroded by wind, water, or wildfires. Seed is readily available and will establish itself into a perennial planting in 1 to 2 years, with very little care needed.

Purple passionflower (Passiflora incarnata), passionflower fruit (P. edulis), and others

Passionflower must surely be one of the most exotic-looking flowers in North America! Its intricate flowers attract hummingbirds, bumblebees, beneficial wasps, and bats. Humans, certainly drawn to its delicious fruit, have used the plant medicinally for hundreds of years.

Passionflower grows very fast and produces delicious fruit that is about the size of a small kiwi. The fruits were an important food for tribes in the southeastern United States, where the plant grows most abundantly. Seeds were found in Algonquian archaeological village sites in Virginia, which dated back several thousand years. Early settlers to this region enjoyed the fruit on their tables as well. John Muir even mentioned passionflower in his A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf; he called it “apricot vine” and described it as a beautiful flower “and the most delicious fruit I have ever eaten, with a semi-tart refreshing flavor.” I can attest that the ripe fruits are quite delicious. They must be harvested quickly, however! Overripe ones quickly begin to ferment and taste very bad, like something moldy or half rotten.

John Muir called passionfruit “the most delicious fruit I have ever eaten.”

Passionflower native species (P. incarnata and P. lutea) grow mainly in the southeastern parts of North America but are hardy to –4˚F, so they are often found in gardens throughout much of the continent. P. edulis occurs throughout much of North America and is known to some as “maypop.” It has always grown in my garden, and it never fails to come back each year in late spring. When passionflower blooms at the gate of my garden, it stops visitors in their tracks with its gorgeous, exotic-looking flowers. Many of them ask if it’s a plant from the tropical rain forest, and they’re always surprised when I explain that it is completely hardy in the lower elevations of Colorado.

In addition to being recognized for its tasty fruit, passionflower is well known as an important herbal medicine. This herb will help you get a restful night’s sleep, calms stress and anxiety, and can relieve mild to moderate pain. Several Native American groups, including the Cherokee and the Houma, used poultices of the leaves topically to heal cuts and bruises.

All aerial parts of the plant are harvested for medicine, and although Passiflora incarnata is the species most often used in the natural products industry, all species are medicinal. Passionflower is currently listed in the European Pharmacopoeia as an official plant medicine. In the United States, it was listed in the National Formulary from 1916 to 1936, where it was approved as a sedative and sleep aid.

The name “passionflower” reflects a story that the flower symbolizes the crucifixion of Christ. Here is the story as it was told to me when I was an herb student more than 30 years ago:

The petal’s purple strips represent the wounds of Jesus. The coronal filaments symbolize his crown of thorns. Three styles and the stamen in the flower’s center stand for the three nails and the hammer that drove them into Jesus’s hands and feet. The calyx and leaf bracts represent the Holy Trinity. The stigmas are Jesus and the two thieves. Petals and sepals become the 10 apostles who were present at Jesus’s crucifixion. The leaves are the hands of the prosecutors, and the tendrils are the scourges that were used to flagellate Jesus as he carried his cross. The ovary symbolizes the Holy Grail. Passionflowers are usually purple, blue, and white; all the colors that represent the King, the heavens, and purity.

Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) and Texas persimmon (D. texana)

A delicious fruit that tastes like pudding; a poultice for warts; a beautiful, dark wood; and a coffee substitute: here is a wondrous tree with so many varied uses! Persimmon can be found in the wild from north- central Texas and southwestern Oklahoma, across the southeastern United States, and down into the northeastern regions of Mexico. The name diospyros is Greek for “fruit of the gods.” The species name is virginiana because early colonists first learned about this fruit from Native Americans near a Virginia colony. It’s called pasimenan by the Algonquian people.

When persimmon fruits are ripe, they are soft — even mushy — with a consistency of pudding. They can be eaten raw by simply opening the fruit and scooping out the insides. The fruit is often made into jams and breads, but pudding seems to be the most popular way to eat a persimmon. The persimmons native to Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma (Diospyros texana) ripen to a dark purplish black and, like all persimmons, are very sweet. They are eaten fresh or cooked into a type of persimmon custard.

Dehydrating persimmons helps deactivate the compounds that can make it astringent when eaten fresh.

Persimmon fruits contain tannins and polyphenolic constituents that give the fruits this astringent quality. As indigenous people discovered, allowing the fruits to be hit by frost inactivates these compounds. Drying has a similar effect, so fruits that were picked before the first fall frost were often dehydrated and kept in storage to be eaten during winter.

Confederate soldiers and civilians in the South during the Civil War often had a difficult time getting food and supplies when the North’s blockade was in place. As a result, they became creative in their efforts to find suitable substitutes for many of the foods and drinks they were accustomed to. Confederate soldiers, along with civilians throughout the South, roasted persimmon seeds and then ground them to brew as a coffee substitute.

Confederate soldiers, along with civilians throughout the South, roasted persimmon seeds and then ground them to brew as a coffee substitute.

Persimmon has been used to treat a number of different afflictions. The Cherokee people picked the fruits just before first frost and made them into an astringent medicinal syrup to treat diarrhea. The Choctaw sun-dried the fruit and baked it into a bread for the same purpose. People of the Catawba tribe made a poultice of the fruit to remove warts and a decoction from the tree’s bark to use as a mouthwash for thrush (a type of fungal infection). The Rappahannock Indians chewed the bark to relieve heartburn.

Persimmons drying in the sun

Powhatan Indians first showed this fruit to early colonists, giving them very specific directions on how to harvest the fruit: they told them to wait until the first frost to eat the fruit. The settlers misunderstood, not realizing that they needed to leave the fruit on the trees to ripen fully. They picked the fruit before it was fully ripe and tried to eat it — and found it far too astringent to be palatable. Captain John Smith of Jamestown wrote, “The fruits like a medlar; it is first green then yellow, and red when ripe; if not ripe, it will drive a man’s mouth awrie with such torment, but when it is ripe, it is delicious as an apricock.” Persimmon became an important food for the colonists, as it was a good source of vitamin C.

It is possible to ripen persimmons picked before the first frost indoors by placing them in a paper sack with either an apple or banana, but the best way to have ripe persimmons is to simply leave them on the tree until they have been subjected to a frost and have ripened on their own. It’s comparable to the difference between a vine-ripened tomato and one ripened on the countertop. The difference in flavor is noticeable.

When a persimmon tree is young, its wood is a beautiful light color and very fine grained. This young wood is strong yet lightweight, making it ideal for being fashioned into all kinds of products, including billiard cues, wooden spoons, archery longbows, drumsticks, and wooden flutes. As the trees grow older, the heartwood becomes nearly black, similar to ebony. It’s an extremely dense hardwood at this point, and a perfect choice for hand-carved golf clubs.

Old persimmon heartwood is very dense — perfect for the heads of golf clubs.

Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa), lodgepole pine (P. contorta), piñon pine (P. edulis), and others

Trees that symbolize wisdom, harmony with nature, and longevity, pines have been important to Native people since ancient times. Is it any wonder that Henry David Thoreau would say of the white pine, “There is no finer tree”? Pines grow throughout North America, and the various species have many of the same uses — from backpackers’ tea to turpentine.

Pine is one of the most common building woods, and lumber from these trees serves as fences and barns on farms and ranches. Homes since the days of early colonists have been built from pine lumber, and it is still an important construction wood today. Pine paneling is used for interior walls, beautiful floors, and furniture such as tables and chairs, bed frames, and china cabinets. President George Washington used southern yellow pine for the floors at his home Mount Vernon.

Before the American Revolution, white pine was in high demand for Britain’s shipbuilding needs, and King George III claimed ownership of all large American white pines. This upset the American colonists, as they needed these trees for many of their own lumber, shipbuilding, and resin purposes. In fact, the tree was so important to them that the first colonial flag featured a white pine in the upper-left corner. During that time, rebellious colonists planked the floors of their homes with white pine, in defiance of the British king.

The pine tree was so important to American colonists that the first colonial flag featured a white pine in the upper-left corner.

Pine resin has a number of medicinal applications. It is a good respiratory herb and a cough expectorant. Its antimicrobial properties make it beneficial for treating infected wounds. In emergency situations in the wilderness, it can seal cuts and wounds closed. I’ve even used it to remove splinters and cactus spines. To do this, I warm a small piece of pitch between my fingers until it is pliable, spread a thick layer of it over the skin where the splinter is embedded, then (after the pitch cools) pull the corner of the pitch up and off. As the resin comes off, the splinter is pulled out, too.

Pine tar soap

Pine trees hold a lot of resin in their bark and wood — which you would know, if you’ve ever grabbed hold of a pine branch and found your hands covered with a sticky substance that doesn’t wash off easily. For the early inhabitants of this continent, however, pine resin wasn’t an annoyance; it had many useful applications. Native American tribes across North America, including the Nez Perce and the Hopi, collected it by either cutting down the tree and debarking it or by tapping a live tree. They used the resin to waterproof their canoes and to treat their baskets for carrying liquids. Colonists saw the advantages of using pine pitch and tar as waterproofing agents for boats and buildings. Pine tar is made by slowly burning small pieces of the tree, along with the roots, in a smoldering fire. The resulting black goo is tar, which can then be processed into things like turpentine.

After the Revolutionary War, the United States became the world’s leading producer of pine resin. There were so many pine trees harvested in the eastern and southern pine forests during this time that something had to be done to regulate the situation; as a result, Massachusetts created the first conservation legislation in the United States that required that permits be issued for the cutting and debarking of pine trees.

Shampoo and soap are sometimes made with pine tar, which is said to be good for loosening scaly skin caused by psoriasis. Dandruff shampoos were historically made with pine tar, but now coal tar is used instead.

Ponderosa pine is easy to identify when you’re hiking through the forest where it grows — from the Plains states west to the Pacific coast, and from southern Canada to Mexico. You’ll suddenly catch a drift of butterscotch aroma (some say vanilla), the scent its bark emits. If you’re wandering through the woods and see someone hugging a tree with their nose to the bark, chances are it’s a ponderosa they’re smelling.

As a young sapling, lodgepole pine was the perfect tree for making tepee poles (hence the name “lodgepole pine”); it’s lightweight and the trees grow tall and straight. Fifteen to 18 of these 2- to 4-inch-diameter lodgepole pine trunks are needed to provide the poles for one tepee. Some Minnesota tribes used red pine, but the wood is heavier and thus wasn’t as ideal for the nomadic life that many tribes led. Today, special harvesting permits for traditional and ceremonial use are required by the U.S. Forest Service in order to cut down lodgepole pine trees for tepee poles.

Lodgepole pines, a subalpine species that needs cold winters with heavy snowfall to thrive, are struggling with the effects of climate change. Their population numbers are dropping as temperatures rise and warm seasons last longer with less precipitation and longer drought cycles. Warmer winters also mean that fewer bark beetles are killed, worsening their already near- epidemic level of infestations. A 2011 study suggests that there may not be many lodgepole pines still living by the end of the century.

Pine needles made as a sun tea are a wonderful source of vitamin C and simple carbohydrates that provide fast energy. This is a good wilderness tea for backpackers, as pine trees grow abundantly in North America and so are readily available. The needles contain five times more vitamin C than lemons do by weight.

In the Southwest we call them piñon nuts, but if you buy them at the grocery store they are normally labeled pine nuts. A traditional ethnic food of the southwestern and western United States and northern Mexico, piñon nuts are an important high-protein food (a 1-cup serving of dried pine nuts supplies a little over 18 grams of protein). They have become a gourmet ingredient in pesto, where just a few handfuls of nuts lend a unique flavor.

This is a crop that is harvested mainly from wild populations of trees, although there are a few piñon orchards, too. Most of the seed is picked by hand from the ground directly under the tree where the pinecones fall in September. Harvesters must work quickly and efficiently, as seed will be snatched up by wildlife if it’s left to linger on the ground. One piñon tree yields about 20 pounds of nuts every 2 to 7 years. It takes 26 months for seed to mature and be ready to pick, so crops aren’t picked annually in most places. Thankfully, the nuts will keep in airtight containers for 5 to 10 years, so they can be stored for later use. Knowing how the seeds are gathered makes it easy to understand why piñon nuts are so expensive at the store. This crop is important economically to the regions where the trees grow, but, as is often the case, most of the profits go to the middlemen instead of to the migrant harvesters.

Coiled pine needle baskets are traditionally made by Cherokee and other southeastern tribes. Western tribes also make these kinds of baskets. There are at least nine species of pine used in needle basketry, with southern longleaf pine (P. palustris) offering the longest needles — up to 22 inches in length. Today baskets are still created with this method, but they are mostly used for decoration rather than practical purposes, simply because they are so labor intensive to make. I speak from personal experience: I made a small basket that is only about 4 inches in diameter, and it was a full day’s project.