Chapter 9

Generating a Dynasty: The Matriarchs

In This Chapter

Joining Sarah on her long path to motherhood

Joining Sarah on her long path to motherhood

Observing Rebekah change the course of history

Observing Rebekah change the course of history

Witnessing the stories of Rachel and Leah

Witnessing the stories of Rachel and Leah

Meeting Tamar, whose bloodline produces Jesus Christ

Meeting Tamar, whose bloodline produces Jesus Christ

L ike your grandmother or mother, a matriarch is a woman who has a profound influence, directly or indirectly, on her family and subsequent generations. Women given the matriarch title are powerful because they inherited it, they married into it, they earned it, or they fought for it. Matriarchs like Queen Victoria of nineteenth-century England or the Empress Maria Theresa of the eighteenth-century Austrian-Hungarian Empire ruled by their wits and wealth, ensuring a dynasty through their children and grandchildren. The matriarchs mentioned in the Bible wore no crowns and did not sit on thrones, but through their deeds and their offspring they established lineages as powerful as any secular dynasty.

Although women often achieve historical prominence through their marriages to important men, some biblical women are matriarchs in their own right, and they’re known for their personal achievements, rather than those of their husbands. These women experienced the complexities of life still common in the modern world — childlessness, deception, challenging marriages, envy of the “other woman,” and hard-to-handle children — but they still managed to remain grounded in their faith to God.

The 12 tribes of Israel

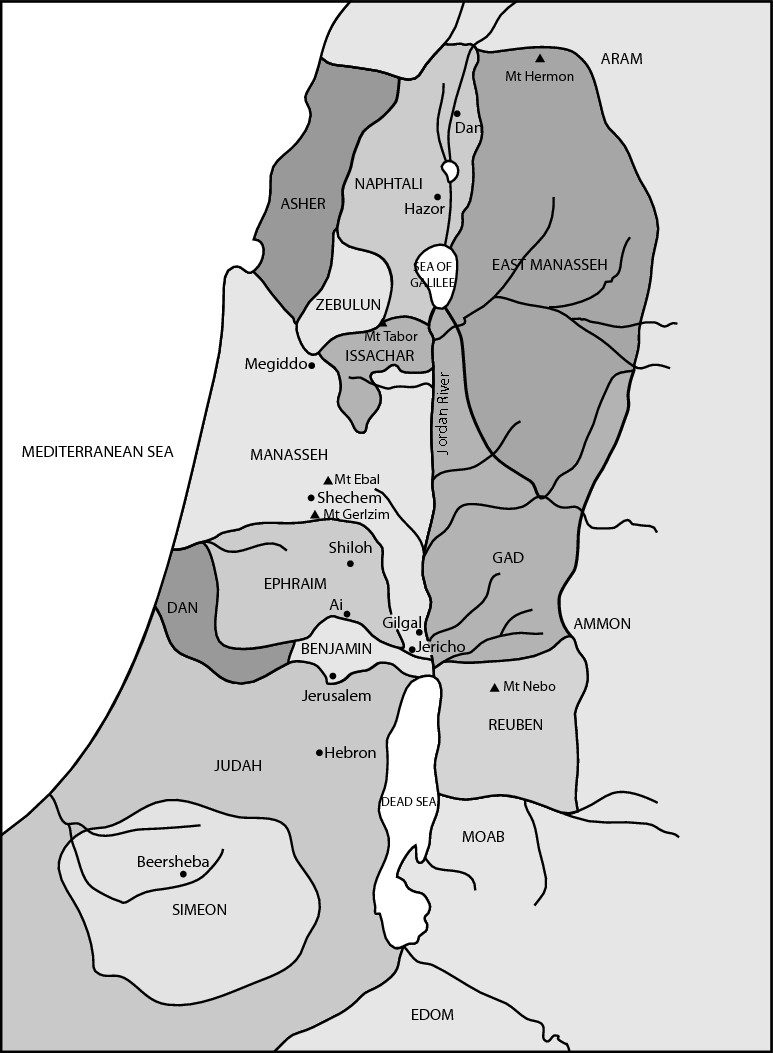

Sarah’s grandson, Jacob, had his name changed by the Lord to Israel, and his 12 sons and their large, influential families literally became the foundation of the 12 tribes of Israel. Each tribe or clan took its name from one of the 12 sons of Jacob, and each tribe occupied a different territory as their numbers grew. Eventually, ten tribes settled into what would later be known as the Northern Kingdom of Israel, while two tribes composed the Southern Kingdom of Judah. The Assyrians conquered the north in the eighth century BC and scattered the ten tribes so far and so well that they are now known as the “Lost Ten Tribes.” The Babylonians conquered the south two centuries later.

Strong-Willed Sarah: Wife of Abraham

Sarah, whose birth name is Sarai (Hebrew for “my princess”), is more than the wife of the biblical patriarch Abraham (who served as a key figure who connected Judaism, Christianity, and Islam). She’s known in her own right for both her actions and words, which helped to influence history. The Bible discusses not only her status but also the pivotal role she played as a mother, wife, and devout believer. As grandmother to Jacob, who later fathered the 12 sons (tribes) of Israel, Sarah is, in fact, considered the ultimate matriarch of the Hebrew nation, the Kingdom of Israel, and Judaism as we know it today.

Traveling with Abraham

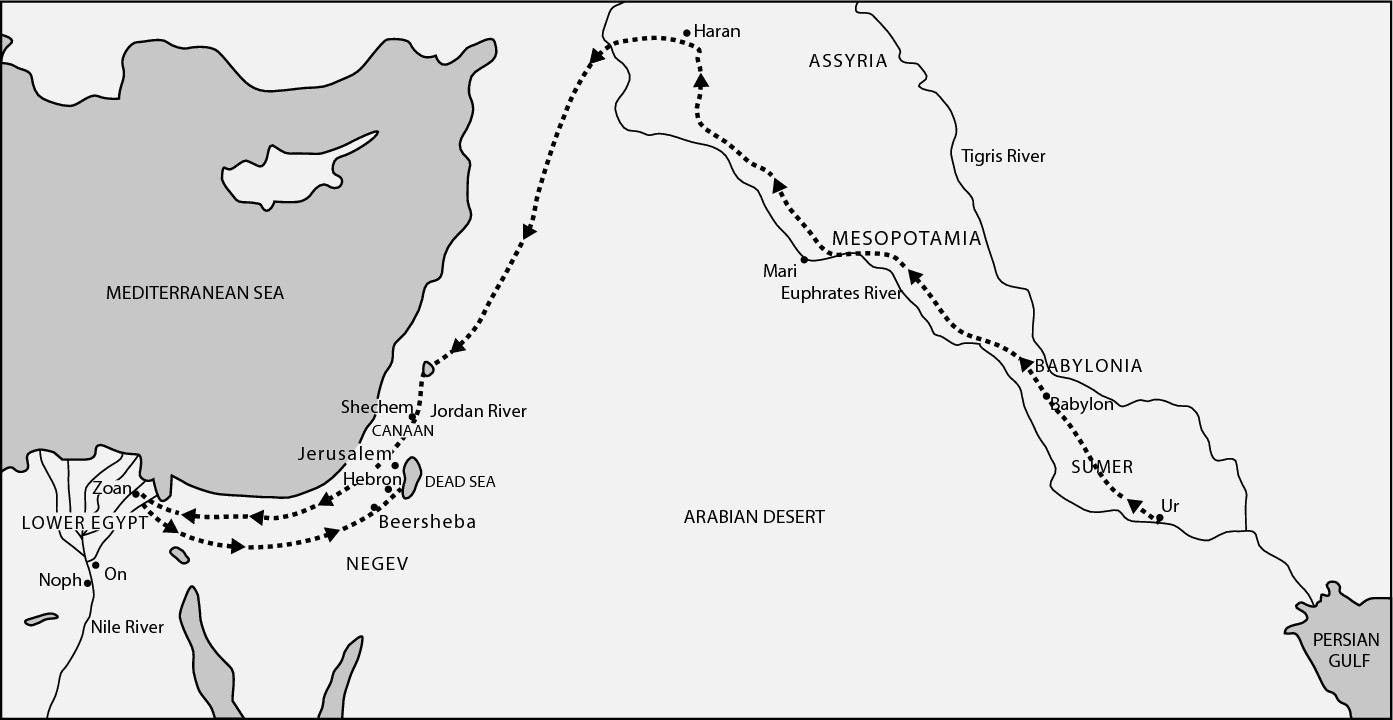

Sarah’s arranged marriage to Abraham leads her through many cities (see Figure 9-1) — enduring many hardships along the way. The two begin their married lives in the city of Ur of the Chaldees (an ancient city of Mesopotamia located in what is now southern Iraq), but then God sends the entire family to Haran (present-day eastern Syria). (See Genesis 11:27–32 for more information.)

Sarah and Abraham are later directed by the Lord to move from Haran to the land of Canaan (which later became the Promised Land), but they’re instructed to go alone, leaving behind the rest of the clan, except their nephew, Lot, and his immediate family, who come with them. (For the details, see Genesis 12.)

Life wasn’t easy on the road, and yet Abraham and Sarah are forced to move again. A famine in Canaan pushes them on toward Egypt. The Bible implies that upon arriving in Egypt, Abraham begins to trust in human ingenuity more than upon Divine Providence. Instead of relying on God to care for his family, Abraham relies on his own wits, using deception when he first meets the ruler of Egypt, Pharaoh. When Pharaoh notices Sarah’s stunning beauty, he is taken with her. But instead of admitting that Sarah is his wife, Abraham insinuates that she is his sister. Abraham makes this move to gain favor with Pharaoh; if viewed as a brother rather than a competitor, Abraham gains security and avoids potential rivalry with the ruler.

And indeed the ruse works. Although there may have been some truth to Abraham’s claim — Sarah may have been his half sister, too (see the sidebar “Next on Jerry Springer: Sarah and Abraham,” earlier in the chapter) — she is first and foremost his wife. Unfortunately for Sarah, Abraham’s deceit lands her in Pharaoh’s harem, where she is treated like property, while Abraham enjoys the spoils of his deception. Her captivity is seen by many biblical scholars to be a foreshadowing of the Israelite slavery in Egypt centuries later.

.jpg)

Next on Jerry Springer: Sarah and Abraham

There is continuing debate as to whether Sarah may have actually been related to Abraham. One theory posits that they’re both the children of one father, Terah, but they have different mothers. Another theory speculates that Sarah is the niece of Abraham — the sister of Lot and the daughter of Haran, Abraham’s brother. Regardless of her parentage, Sarah eventually married Abraham. Many scholars also believe that she probably came from some aristocratic background, based on her name and also on the fact that she and Abraham had an arranged marriage, a practice of the more influential families of the day.

If the speculations about her relationship to Abraham seem unsavory, marrying close relatives was actually not uncommon in ancient times, especially among nomadic peoples. Incest then was defined as marriage between a son and mother, a daughter and father, or a brother and sister who shared the same mother (sometimes called uterine siblings). Marriage between half siblings (by the same father), cousins, nieces and uncles, or aunts and nephews weren’t considered incestuous until after the Law of Moses (called the Mosaic Law), which came centuries later.

The fraud doesn’t last long; God punishes Pharaoh for his adultery with Sarah by sending a plague. Pharaoh then figures out that he has taken another man’s wife — a practice considered taboo, even for Egyptians at that time. Sarah is returned to Abraham, and the gang is deported from Egypt. Abraham and his family then settle back in the land of Canaan, as God had originally directed. (For more details, see Genesis 12:10–20.)

Ironically, Abraham has yet to learn his lesson. The hoax is repeated in Genesis 20, after the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, when Abraham allows another ruler, King Abimelech, to take Sarah as his wife under the pretext that they were only half brother and half sister. Whereas Pharaoh deduces on his own that Sarah is really Abraham’s wife (after being besieged with plagues), God tells Abimelech in a dream about her marital status and gives a deadly warning not to commit adultery.

This duplicity of Sarah’s husband is an attempt on his part to save his life, while God intervenes with plagues, dreams, and threats to preserve this good woman despite her husband’s political maneuvering. Sarah is rejoined with Abraham a second time. She remains faithful to both her husband and God and will later become as devoted as her husband, Abraham, to God’s covenant. (See the section “Taking a new name,” later in this chapter, for more on the covenant.)

The third time’s a charm: A son at last

In the sixteenth century AD, King Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church and Pope in Rome by making himself supreme head of the church in England. He did this because his wife, Queen Catherine, couldn’t produce a male heir (their only surviving child was Mary I). He divorced Catherine and married Anne Boleyn, who gave him only another daughter (Elizabeth I), so he later divorced her, too. He then married Jane Seymour (no, no, not Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman), who was the mother of Edward VI. That was nearly 3,000 years after Sarah and Abraham, but the influence of the patriarchal society could still be seen. By contrast, Abraham remained a faithful husband to Sarah until she directed him to do otherwise.

Becoming a mother

Sarah is infertile, which creates a precarious situation for herself and her husband. Without sons, upon whom a patriarchal society depends, her family will have no dynasty and no future. Being childless was both dangerous and embarrassing in ancient times because it meant you’d have no one to care for you when you became too old to support yourself — and no one would be around to carry on the family name. Worried about this inevitability, the self-reliant Sarah comes up with a solution. She gives her slave girl, Hagar, (see Chapter 15) over to Abraham so that Sarah can obtain children by her, as described in Genesis 16:1–3.

This action isn’t considered an act of bad faith. It is seen as a sacrifice of love: love of husband and love of nation. Sarah is willing to share conjugal rights and allow another woman to have her husband’s son. Only after the birth of Ishmael, Hagar’s son, does God reveal that Sarah would finally be a mother in the fullest sense and not just by surrogate. Even Paul extols her fidelity to husband, people, and God in his Epistle to the Hebrews: “By faith also Sarah herself, being sterile, received power to conceive, even beyond the age of childbearing years, since she considered the one having promised [God] faithful” (a literal translation of the original Greek; Hebrews 11:11).

Offering up her slave girl to her husband must have taken great strength of character for Sarah. Yet some people believe that she does this for the love of her husband and of her potential nation because, without a male heir, the lineage ends. Sarah is Abraham’s only wife, she is beyond the age of childbearing, and so the stability of the dynasty is threatened. The paradox is that God had promised Abraham he would be the father of many nations, and yet Sarah is apparently barren. By putting aside her own desire to have a child, Sarah embraces a broader perspective through the custom of the day — surrogate motherhood — to ensure the survival of the Hebrew nation.

Because she was willing to make such a difficult decision — allowing her maidservant to have a child with Abraham — scholars often consider Sarah to be one of the “founders” of the Hebrew nation, along with her husband. As it turns out, the Jewish people are not traced to Hagar’s son, Ishmael, but to Sarah’s son, Isaac (whom she finally gave birth to at the age of 90). Despite the fact that it is Sarah’s wish, Hagar’s carrying Abraham’s baby causes animosity between the two women. Sarah accuses Hagar of treating her with contempt, and she blames Abraham for not being more attentive to her needs in preference to his concubine. Abraham responds by giving Sarah permission to mistreat and abuse Hagar, who in turn escapes from her angry mistress. (For more details, see Genesis 16:4–6.)

To rectify the situation, God sends an angel to Hagar to convince her to return as Sarah’s servant, as described in Genesis 16:11–12. Hagar does return and gives birth to Ishmael, whose name means “God hears.” Ishmael, the son of Abraham and Hagar, will later become the father of the Ishmaelites, the ancestors of modern-day Muslims and believers of Islam.

Taking a new name

Sarai’s name is changed to Sarah (and her husband’s to Abraham) when, at 99 years old, Abraham makes a covenant (a sacred, permanent, and complete bond) with God, in which Abraham agrees to establish the Hebrew nation. (Genesis 17 has all the details.) Name changes are signs of new missions in life, signifying the importance of this covenant and of the new Hebrew nation, which will later become the Kingdom of Israel — and the home to the religion of Judaism.

Like her husband’s change of name from Abram to Abraham, Sarai’s change to Sarah is not as dramatic as her grandson’s (Jacob, who became Israel). Nonetheless, a change in name is very rare in scripture, and God is the one who makes the change, so that gives it some extra importance as well.

Soon after, the 90-year-old Sarah gives birth to a child, further underscoring her new mission (Genesis 17:17; 21:1–7).

Sarah has a son, whom she and Abraham name Isaac. But a family feud erupts. Ishmael, the son of the slave girl Hagar, is about 15 years old when Isaac is born, and allegedly mocks his baby brother, Isaac. Sarah orders that Hagar and Ishmael be banished, which causes Abraham great distress because he is very fond of Ishmael. But God assures him that if he gives in to Sarah’s request, Ishmael will still become the father of a great nation himself.

Sarah’s tenacious protection of son Isaac can also be seen as more than just maternal. Like her husband, she knows that through Isaac, the Hebrew people will become a nation. Sarah perceives Ishmael to be such a rival that she abuses Hagar to the point that she drives the mother and son away, thus leaving Isaac and his inheritance intact. Protective mothers may not always act rationally or logically, but their motivation is clear: love and devotion to their children. In this case, Sarah’s motivation is also love and devotion to God’s covenant with Abraham.

Succumbing to a broken heart

After becoming a mother for the first and only time at the ripe old age of 90, Sarah lives to the age of 127 years, according to Genesis 23:1. An old rabbinical legend from the Talmud says that she dies of a broken heart. (The Talmud is the collection of ancient extra-biblical rabbinical writings from the third century AD that are considered authoritative by many Jews; the Talmud is equivalent to the Christian Patristics, the writings of the church fathers from the first to fifth centuries AD) Allegedly, Sarah sees Abraham take their son Isaac to Mount Moriah, where God asks that the boy be sacrificed as a sign of complete loyalty.

Thinking that her only child is about to be killed at the hand of his own father, she supposedly dies of a broken heart. An angel stops Abraham, however, before he is about to slay Isaac, but it’s too late for Sarah. Her husband and her son return to camp to find her dead. Abraham purchases a cave, where he buries his beloved wife and where he himself will later be interred. (For the details, see Genesis 22.)

.jpg)

Honoring Sarah

Sarah was physically unable to have children on her own. Her faith, however, is extolled even in the New Testament (she is mentioned in Romans 4:19, Romans 9:9, and 1 Peter 3:6). She never lost hope that somehow God would work things out. Divine intervention helped her get pregnant, but only after a long lifetime of barrenness and the cultural shame it brought. Her patience, despite many years of being considered barren, her perseverance despite being discarded twice by her husband, and her strength to defend her offspring and her own people are qualities that make her worthy of the title matriarch.

The memory of Sarah is still honored to this day. A mosque is built over her grave, where she lies beside her beloved husband, Abraham. According to the Qur’an (sometimes called the Koran; the sacred writings of Islam, which are believed to be the revelations of Allah to Mohammed) and Islamic tradition, Sarah is revered not because of her marriage to Abraham but because she was the “mother” of two great prophets, her son Isaac and her grandson Jacob, just as Hagar is revered for being the mother of the prophet Ishmael.

Wily Rebekah: Wife of Isaac

Rebekah, sometimes spelled Rebecca, is the daughter-in-law of Sarah, Abraham’s wife. (Rebekah means means “noose” in Hebrew.) Rebekah is best known for her ingenuity, cunning, and ability to shape history — instead of allowing history to shape her .

We first meet Rebekah as Abraham’s servant, Eliezer, comes upon her at a watering hole. Eliezer has been sent to find a suitable wife for Isaac, Abraham’s son. (See more on this meeting in the next section, “From a watering hole to a wedding.”)

Rebekah is at first seen as kind and beautiful. But she is also a woman of determination, which you shall later see when she schemes to secure the lineage of her younger son. Rebekah’s tale serves as a reminder that all actions have consequences. Her conspiracy to steal a birthright for her younger son leads to a broken relationship with her eldest and the eventual departure of her youngest.

Nevertheless, Rebekah’s actions do change the course of history, and although she uses questionable methods, her motivation isn’t entirely selfish. Like her mother-in-law before her, she had a desire to preserve the fledgling Hebrew nation. She knows her sons better than anyone, even their father. She can see that the eldest is too immature, preoccupied, and disinterested to be the leader of a great people. The younger son has the determination, talent, drive, and capability to lead. It isn’t his fault that his twin brother came out of the womb first, but it doesn’t change the fact that whoever is born first gets the birthright.

Rebekah is as much a matriarch as Sarah in that they’re mothers of great children who become leaders of the people. They’re completely devoted to the family as such, and they put their personal interests behind those of their husbands, their children, and even their own people. Rebekah’s intervention allows Jacob rather than Esau to continue the lineage.

From a watering hole to a wedding

Eliezer travels to Haran in search of a wife for Isaac. There, Eliezer stops at a local watering hole (literally — we’re not talking about a bar here), and he prays to God. He says that whoever gives him and his camels a drink of water will be the future wife of Isaac. Rebekah soon appears, offering water to both Eliezer and his camels. Eliezer finds Isaac’s match. He showers her with gifts of gold and tells her about his master, Abraham, and his master’s son, Isaac.

Rebekah’s family, especially her father and brothers, love her dearly, and they don’t want her to leave, even though they share her joy in finding a good husband. They try to persuade her to stay in Haran rather than follow Eliezer, who seeks to bring her to Isaac in Canaan with Abraham. Besides their fondness for Rebekah, they may have been considering Isaac’s inheritance as an only son. (For more details, see Genesis 24:15–55.)

If Rebekah stays with them and Isaac joins her, then their clan will benefit from the spoils of marriage. On the other hand, if she leaves, her family will not see her nor will they benefit from her husband’s inheritance. Because Abraham is still alive, Isaac doesn’t yet own the legacy. So perhaps Rebekah’s family merely wants to wait until Isaac actually inherits the estate before they consent to the marriage. Regardless, she chooses to go with Eliezer immediately to visit Abraham and meet her future husband, Isaac. Whether she is totally motivated out of love for her fiancé or if a part of her can’t wait to get away from her possessive father and brothers, no one will ever know for sure.

Although ancient weddings certainly didn’t have the pomp and circumstance of today’s Charles-and-Diana–style royal weddings, they were special in their own way. For example, Isaac honors Rebekah by consummating his marriage to her in the tent that belonged to his mother, Sarah. Isaac was a devoted son to his mother during her life and after her death, and this act represents a true honor to his new bride. (For more details, see Genesis 24:62–67.)

Following in Sarah’s footsteps

Despite this early honor in her mother-in-law’s tent, Rebekah later receives the same shabby treatment that Sarah encountered before her. Just as Abraham allowed Sarah to be taken by Pharaoh and then Abimelech under the pretense that she was merely his sister (see the section “Traveling with Abraham,” earlier in this chapter), Isaac too portrays his wife, Rebekah, as his sister to guarantee protection for himself. He fears, just as his father did with Sarah, that his wife’s beauty will make him a target, so he allows his wife to be taken by Abimelech (king of the Philistines) into his harem. (This Abimelech is most likely the son of the Abimelech who took Sarah.)

The fraud is soon exposed when Abimelech catches the two lovebirds in a romantic embrace — not something a brother and sister ought to be doing. So he concludes the obvious: They’re not siblings but spouses. (Read this story in Genesis 26:6–11.)

In each case, both Isaac and his father, Abraham, fear for their lives and are willing to sacrifice the virtues of their wives. Despite her husband’s duplicity, Rebekah, like her mother-in-law, doesn’t retaliate with infidelity or disrespect.

Rebekah shows strong character in that she is willing to endure even temporary injustice for a higher good (saving her husband’s life if he was, indeed, in danger because of her beauty). Isaac most likely fears that the king will try to get him out of the way because of his marriage to the young, beautiful Rebekah. Even though nonexistent, the threat to his life is taken seriously by Isaac, enough to feign a brother-sister relationship. (For the details, see Genesis 26:6–11.)

Tricking her husband

Like her mother-in-law, Rebekah experiences infertility. But after 20 years, Isaac’s prayers to God on behalf of his wife are answered, and Rebekah finally becomes pregnant — with twins.

The eldest twin, Esau, is a chip off the old block — a hunter, a jock, and an outdoorsman. Jacob, the younger son, is the tent dweller — academic, introverted, and a big thinker. Where Esau takes after dear old dad, Jacob is his mother’s son, with all her wit and wisdom. Through Rebekah’s prayers, God tells her that her two sons represent two nations, one stronger than the other. He also tells her that the elder, Esau, will serve the younger, Jacob. This cryptic prophecy takes time to unfold but comes to pass nonetheless.

Rebekah’s two boys are the most competitive the world has ever seen. She favors the younger, Jacob, while dad gives more attention to the older son, Esau. But Esau is neither swift nor sensible when mother and son scheme to dupe the old man and cheat the birthright from him. First, sibling rivalry took a new turn among these twins when Jacob tricks Esau into surrendering his birthright as eldest son. After a long day of hunting, the elder brother (Esau) is so hungry for a hot meal that he agrees to ‘sell’ his birthright to his younger brother (Jacob). The price for the birthright? A bowl of porridge in exchange for the ancestral heritage! (See Genesis 25:29–34.)

Then, Rebekah hatches an I Love Lucy plan to have Jacob impersonate his brother. She contrives a conspiracy to dress Jacob so that the blind and hard-of-hearing Isaac, now on his deathbed, will think Esau has arrived for his final blessing. Given some animal skins and oils, nerdy Jacob is transformed into his brother Esau. Jacob brings his dad some cooked game, and although Isaac thinks he recognizes Jacob’s voice, the disguise that Rebekah devised still fools the blind old man. The hairy hands (from the animal skins) and the odor (from the oils) appear to be Esau’s. After supper, Jacob gives Isaac some wine and then receives the blessing intended for his brother. (For more details, see Genesis 27:1–29.)

Perhaps it’s Rebekah’s way of getting back at Isaac for the plot to pass her off as his sister, or perhaps it’s a ruse to get the better-suited candidate, Jacob, the job as leader of the pack. Nevertheless, the plot works, and Isaac erroneously gives Jacob Esau’s birthright.

As a result, Jacob must leave town for fear of Esau’s revenge; Esau has vowed to kill his brother in retaliation for stealing his birthright. Jacob is sent by his father, Isaac, to stay with his Aramean uncle Laban, his mother’s brother, in the town of Paddan-Aram (in Mesopotamia, near Haran). Although Rebekah doesn’t want to say goodbye to Jacob, she also understands that Esau means business, so she arranges for his departure. This is the last time she will ever see her son. She spends the rest of her days with a son she betrayed and a husband she deceived, while her favorite son will not return until after she is already dead and buried. (For more details see Genesis 27:1–46.) This is the last we hear of Rebekah in the Bible.

Part of the mystery of the Bible is that it often doesn’t give all the answers but many times prompts more questions. Although it was God’s plan that Jacob get the blessing and birthright rather than his older brother, God didn’t force or even persuade anyone to deceive or do anything immoral. Every human being has a free will, and God can use that free will to achieve his purposes even when humans go astray. The old saying “God can write straight with crooked lines or paint masterpieces with broken brushes and canvasses” is certainly true. This is the mystery — that God allows or permits evil or sin to occur because he knows that a greater good will come from it. Because God doesn’t directly cause the evil, we call this his permissive will as opposed to his ordained will.

Rachel and Leah: Wives of Jacob

In addition to the fierce sibling rivalry between brothers (Esau and Jacob, discussed in the preceding section, “Tricking her husband”), the Bible also tells about the struggle between two sisters, Rachel and Leah. With the boys, competition fuels the flames; among the girls, it is daddy who is to blame. Laban, their father, uses these women to achieve his own ends and winds up pulling a fast one on Jacob. Both women eventually marry Jacob, and both will become matriarchs as a result of their offspring leading the nation. Both women also prove to be strong in character and wisdom.

Helping to shape a nation

Despite the sibling rivalry between Leah and Rachel and Jacob’s obvious favoritism for Rachel, these two women helped shape the destiny of a nation and a people. Their children and the children of their servants became the foundation of the 12 tribes of Israel. Their personal struggles and challenges mirrored that of their future progeny and the subsequent kingdom. Israel as a nation, kingdom, and people later experienced similar disappointment, betrayal, rejection, and suffering but also endured as the people of the covenant, the Chosen People. Rachel and Leah helped make that happen, and their lives also reflected the growth and growing pains the nation would soon undergo. Just as there was tense rivalry between the two sisters, so there was some strong competition among the clans and tribes that composed the Israelite nation. Just as the mothers of the 12 sons of Jacob (also known as Israel) competed with each other, so, later, did the 12 tribes compete. The Danites (members of the tribe of Dan) rumbled with the Benjamites (members of the tribe of Benjamin) and so on.

Meeting Rachel; marrying Leah

When Jacob, Rebekah’s son, first meets Rachel, his Uncle Laban’s beautiful daughter, it is love at first sight. He even gives her a kiss (Genesis 29:11), which seals their hearts forever.

Smitten by love, Jacob makes a deal with Laban to stay and work for seven years, at the end of which he will be given the hand of his beloved Rachel in marriage. Meanwhile, it is soon clear that Laban definitely shares some family traits with his wily sister, and he begins plotting in true Rebekah style. The deception involves the beautiful Rachel and Laban’s older daughter, Leah.

Seven years go quickly for a man in love, and Jacob prepares for marriage to Rachel. On the wedding night, however, Laban double-crosses Jacob, disguising his eldest daughter Leah for Jacob’s true love, Rachel. Because the bride wears a veil covering her face, Jacob doesn’t realize that he married the wrong sister until the morning of the honeymoon. And Laban’s big con is successful.

But Jacob isn’t deterred, even when Laban tries to justify his deception, explaining that custom dictates that he marry off the older daughter before the younger. Now Laban tries to use the customs of the day — which Jacob himself had formerly disregarded by tricking his brother — to rationalize his own deceitful actions. Ironic, isn’t it? (For more details, see Genesis 29:21–30.)

But Jacob is still madly in love, so he commits to another seven years of service to Laban for Rachel’s hand in marriage. Finally, 14 years after their first kiss, Jacob marries his first and true love, Rachel. Leah remains his first wife. Both sisters, however, will enter a sibling rivalry second to none when it comes to procreation.

Struggling for favor

Although it wasn’t Leah’s fault, Jacob blames Leah for Laban’s deception. He offers Leah little affection while still doting on her beautiful sister, Rachel. God, however, takes pity on Leah and blesses her with fertility, giving her and Jacob six sons and a daughter, but Rachel remains barren for many years, until she finally gives birth to two sons.

The sisters also resort to using aphrodisiacs (which are called mandrakes in Genesis 30:14) in a contest to have Jacob’s children. Leah is the first to have children, which makes her sister, Rachel, envious. Rachel at that time is unable to conceive so, to catch up with her sister, she gives her maid, Bilhah, to Jacob as a wife, who mothers two more sons for Jacob. Leah is no longer able to have her own children, so she reciprocates and has her maid, Zilpah, give birth to two sons from Jacob.

Escaping Laban

Neither Rachel nor Leah remains fond of their father, Laban, after his deception and the havoc he wreaked on their lives. Not only did he trick Jacob into marrying the wrong wife the first time, but after 14 years of service, neither Jacob nor his wives see a penny of his profit (the wages and livestock Jacob should have been given), which Laban has hoarded for himself. So the sisters and Jacob sneak away from Laban’s house in the middle of the night. Unbeknown to Jacob, Rachel pilfers some of her dad’s golden idols. (Genesis 31:1–21 provides all the details.)

|

Figure 9-2: The territories of the 12 tribes of Israel. |

|

Laban pursues his daughters and son-in-law and eventually finds them. Rachel literally sits on the idols when her father enters the tent, and makes an excuse not to get up. Several Bible commentators hypothesize that she probably hoards these for superstitious or sentimental value, rather than for their trade-in value.

Laban and Jacob eventually come to an impasse, forcing them into a peace treaty. Rachel and Leah (see Figure 9-3 for one artist’s portrayal of them) and their children leave safely with their husband, Jacob, and depart from their father for a second time, never to see him again. These sisters, while different, are united in their love for their new family. Both sisters leave their father and brothers behind and move away with one husband between them. Though escaping devious dad may have held some attraction, moving away from lifelong family connections will be no walk in the park. Nevertheless, Rachel and Leah come together despite their differences and do what is right — obeying the Lord, who had commanded Jacob to pack up and leave.

Rachel dies giving birth to her second son, Benjamin (Genesis 35:16–20). The Bible mentions Leah only one more, when she is buried near Jacob in the same place with Abraham and Sarah and Isaac and Rebekah (Genesis 49:31).

|

Figure 9-3: Rachel and Leah by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882). |

|

Tate Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Tough Tamar: Mother of Perez

Tamar is a Canaanite woman who married Er, the eldest son of Judah (one of the 12 sons of Jacob, who came to represent one of the 12 tribes of Israel). A resourceful woman who remained courageous despite the treachery of some of her relatives and contemporaries, Tamar perseveres and becomes a matriarch whose bloodline eventually produces King David and Jesus himself. (Matthew 1:2–16 explains the family tree.)

The relevance of her actions can’t be underestimated, as she preserves the bloodline that eventually led to the birth of Jesus, whom Christians consider the Messiah — the eventual savior of all women and men, Jew and Gentile alike.

In reading about Tamar, you can see that her ingenuity and tenacity give her the strength to persevere despite almost overwhelming obstacles and disappointments. She proves that women can be as wise, astute, and clever as their male counterparts in using the system to their benefit. She is a model to anyone who experiences adversity, tragedy, opposition, and frustration, and she serves as an example of one who never gives up or becomes too discouraged. Rather, Tamar takes her destiny into her own hands and does what she needs to do to survive.

Losing two husbands

Tamar’s husband, Er, does something to offend God — though the Bible doesn’t say what — and Er is struck dead because of his sin, leaving Tamar childless. At the time, the law of the land, levirate law, dictates that one of her husband’s brothers should marry her, becoming a surrogate father. So Er’s brother Onan (another of Judah’s son’s) takes Tamar as his wife. Unfortunately for Tamar, Onan isn’t eager to have a son because the law also dictates that any son produced is still legally considered his dead brother’s. Thus, this son receives any family inheritance. With no offspring, the property goes to Er’s surviving brothers, Onan being one of them. (See Genesis 38:1–9 for the story.)

Motivated by greed, Tamar’s second husband also offends God, suffering the same fate as the first. While consummating the marriage, he performs coitus interruptus :

—Genesis 38:9–10

Shelah is the next son of Judah in line to marry Tamar, but he isn’t yet old enough to take over his husbandly duties when Onan is struck dead. Tamar’s father-in-law, Judah, asks her to wait patiently for him and then sends Tamar to live as a widow at her parents’ home (Genesis 38:11).

According to custom, if a man has no son over 10 years old, he can perform the levirate obligation himself, but if he does not, the woman is declared a free widow and may marry again. Judah could have released Tamar because two of his sons had already died and the remaining son, Shelah, is too young to marry her, but he chooses not to do so. Tamar can’t remarry, and she must remain chaste. Tamar suspects that her father-in-law will never allow his remaining son to marry her, because the other two sons died soon after marrying her. Her future is up in the air.

Outsmarting Judah

Tamar takes her marital situation into her own hands, and she outsmarts Judah. During the years after his sons’ deaths, Judah’s wife had died as well. After a period of grieving, he takes a trip to have his sheep sheared. The trip takes him past Tamar’s town, where she is still living in limbo with her parents. She forms an idea for vindication. She takes off her widow’s garment and puts on a new dress and veil, positioning herself outside the temple area where Judah will pass. He sees her (see Figure 9-4 for one artist’s depiction), thinks that she is a temple prostitute, and has sexual intercourse with her. He has no money with him, so he leaves her a pledge — his signet ring and a cord and staff — items of good faith akin to leaving a credit card and driver’s license. (See Genesis 38:12–19 for the details.)

The next day, he sends payment with his servant, but the servant can’t find the prostitute to retrieve Judah’s personal effects. No one ever owns up to being the prostitute, so Judah dismisses the event and never retrieves his things. Meanwhile, Tamar soon discovers she is pregnant. Three months go by, and Judah hears through town gossip that Tamar, his daughter-in-law, is now pregnant. Judah, of course, doesn’t know that he is the father or that Tamar is the woman he slept with! He shows righteous indignation and calls for her execution.

Tamar had planned for this possibility, however, and asks Judah to find the owner of the signet ring, cord, and staff from the man she had slept with. He realizes now that he is the father. He is also the one who had refused to allow Tamar to marry his son Shelah, which would have prevented this predicament. Judah now does the honorable thing and takes care of Tamar and her soon-to-be-born twins: “She is more in the right than I, since I did not give her to my son Shelah” (Genesis 38:26).

|

Figure 9-4: Judah and Tamar by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (1621–1674). |

|

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

Tamar’s cleverness allows her to protect the lineage, giving birth to twins, Perez and Zerah. She thus restores two sons to Judah, who had lost Er and Onan to their sins against God. Perez will become a direct ancestor of King David and, later, Jesus Christ.