Two phone calls.

Anna, exploiting our recent membership of the John Clare Society, made contact with Eric Rose. Mr Rose was married to Dorothy Muriel Stokes, Clare's great-great-granddaughter. Anna's researches among her Rose relatives turned up an Eric, and she became quite excited, thinking that the link her father claimed was about to be proved.

Mr Rose is elderly and not to be drawn out. He has no knowledge of Whittlesey, Ramsey or Glassmoor. He refuses to surrender an address. He has no interest in adding peripheral members to an already complex family tree. There are too many Roses, and not a few thorns, dressing the ground: Peterborough into Norfolk, into Suffolk, and as far afield as Dorset. The Hadmans, breeding more modestly, never strayed more than a mile or two from the shores of the Mere. It began to look as if Stilton was their frontier; peasant-labourers in the hills to the west, go-getting farmers and butchers in the flatlands to the east. Clare territory, without a doubt, but we could discover no blood relatives. Just endless, frustrating hints: Beryl Clare (born 1938), another great-great-granddaughter of the poet, married Douglas Harrison. Nellie Rose, sister of Florence (Anna's grandmother), also married a Mr Harrison. Roses and Clares both allied themselves with Reads. At such a distance, we are all part of one great family whose only ambition is to put as much mileage as possible between itself and any dubious third and fourth cousins. (Particularly those who make importunate phone calls.)

A second ring: Professor Catling from Oxford. He has been cruising the Net and come up with a narrowboat, available, if we make an immediate booking, at the weekend. Ship out from March on the Middle Level, down the Nene (Old Course) to Ramsey; and then, if we have sufficient time, and haven't come to grief on a low bridge, round to Whittlesey and Peterborough. By slow and secret backwaters. Sounds good. Do it. Make the call.

Anna, overhearing this conversation, offers to join the crew: a first. Catling boat trips, after early experiences out of Norwich, are usually avoided. Especially when they head down the Thames, out to sea, with competitively drunk, drugged or deranged skippers: Hunter S. Thompson awaydays. (No insurance, no charts, one life-jacket – childsized – shared between five large adults.) But the thought of going by water into Rose country is a temptation not to be resisted.

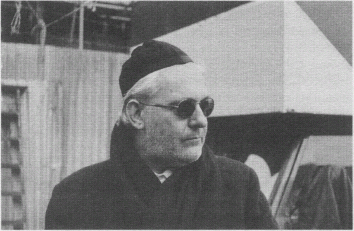

Much food, in Anna's generous fashion (cook in expectation of the entire family, plus friends and lovers, appearing at your table), has been loaded into the car when Catling demands a Tesco's pit stop in Huntingdon. He's working his own interpretation of the Atkins diet and presents a more svelte and compact figure than the Wellesian cigar-chomper of my Oxford visit. This is nothing new, the man has always been a shape-shifter; an ability that stands him

in good stead as a certified performance artist. One day: fabulously bouffant, silver-minted. And the next? Cropped like Magwitch. One day, full-cargoed, under sail; the next, hunched, shuffling, Sherlock Holmes overplaying the vagrant. The range, by his reckoning, runs from early Charles Laughton to eye-patched John Wayne being winched on to his horse. A preternatural ability to swerve, on the beat, from clubbed pathos to diabolic intensity.

This is a very forgiving diet: high protein, no carbohydrates (to speak of), exceptions made for five-star restaurants. Essentially, it involves stocking up on yards of Cambridgeshire bacon, fish bits, lamb; no poncing about with green stuff. Skewer the lot, stuff them with garlic, cook slowly. And meanwhile keep the Blood Marys coming by the pitcher. That was Catling's spin on Atkins: no whisky, not the first day out, but steady vodka (the reformed drinker's friend); the day's vegetable intake coming from tomato juice, spiced with tabasco, Lea & Perrins, lime and a fistful of ice-cubes. Tremendous self-discipline; he'd lost half a stone in a couple of weeks and looked nothing like Nigel Lawson (that absence, that empty suit). To keep up his strength, between jugs, Catling padded his loose jacket with cellophane packets of sliced corn beef.

The March boatyard is a live-and-let-live, take-us-as-you-find-us operation; keys, tour of the craft – fridge, double-bunk, TV, hot shower, Calor gas – and cast off. Boat-builder Harold Fox's son-in-law lets Catling grab the tiller (narrowboats are virtually indestructible, if you don't smoke in bed, or chop up the deck for a barbecue). ‘River cruiser, is it? Out on the Thames?’ says the boatman, as Brian fumbles the gears. But the professor compensates by making an immaculate U-turn, sweeping us back upstream towards the yard.

‘Where you heading for then?’

‘Ramsey.’

Silence.

‘Ram-sey?’

‘Ramsey.’

‘Any special reason like?’

Nobody, in the history of Fox's Yard, has admitted to Ramsey as a voluntary destination.

‘Nice pub, Outwell way. Some folk reckon on Cambridge.’

‘Ramsey. Family.’

‘Ramsey, right then.’

Anna, instantaneously, is a figurehead at the prow, hand on hat. Catling manages the craft with insouciant command: the first Bloody Mary, first Toscani cigar (black as a camel's toenail). The pace is seductive, a brisk walk. The engine purrs. We lie on the surface of things, fields and farms hidden behind earth banks. We drift, drift downstream towards Ramsey.

‘Where are you going?’ shouts a dog-walker.

‘Ram-sey.’

‘Ramsey. Oh. Good luck then.’

Promised rain holds off; clouds are pressing, agitated. Pylons and radio masts are our event horizon. Concrete bunkers, overgrown, have a forlorn freight: distressed history. The engine thuds softly. Hours pass without register. Anna's sense of well-being is palpable. I take over the tiller and Brian manoeuvres his way around the outside of the boat to join her in the bows. They are very old friends. He's been coming to our house since his student days. He is our daughter Fame's godfather. Now, in the suspension, the steady rhythm of the narrowboat's progress down the old Nene, there is confirmation that this is the right, the only possible place to be. Mile by mile, river-time unpicks the Clare walk; a ballast of unnecessary facts is quietly offloaded. Being on water is entering the dream; junking futile quests, letting go.

The Nene thickens, surface slime tangles itself around the blades of the propeller, but doesn't slow our progress; nobody has travelled this way in months. We don't pass another boat. No humans, a mile out of March, walk the river bank. Coming free of green sludge, cloudscapes are reflected in a vitreous carpet. Broken bridges are ruined craft, no farm-worker goes near them. ‘Cock-up bridges,’ they say: humped memorials to the ancient causeway system.

As pale sun breaks through, the golden hour, we arrive at Benwick; a hamlet backed into a bend of the river, between Rose farmland and Ramsey Mere. We make fast in the local version of a bayou: drooping willows, creepers, rickety dock, burial ground (everything but the alligators).

Prismatic shafts splinter heavy foliage. The Benwick church has gone, pulled down, leaving nothing but a brick altar in a field of nettles: ‘Site of the Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, 1850–1980.’ Gravestones diminish into an allotment patch, before the open fields begin. Dead Roses are here too: Thomas William Brittan Rose, son of William and Louisa, died 27 January 1909, aged twenty-two years. Henry William Brittan Rose, his brother, died 14 June 1912, aged twenty-three years.

We moor for the night, a mile or two shy of Ramsey, beside a Waiting for Godot tree; a skeletal black stump on which perch cormorants, pretending to be vultures. Catling cooks a notable feast, skewered fish and bacon, complemented by Anna's chicken. Much wine. Crimson sunset. A crash into dreamless sleep (the voyage is the dream) interrupted by my screams as I wake to spasms of cramp, which hurl me, swearing, to the floor. The twisting and lifting of narrowboat life isn't doing much for my back, but a companionable torment is a small price to pay for the gain in mental space: fresh night air, stars, when I sit out on deck, to watch the cormorants watching us.

Dawn skies squeeze us closer to the water, which is smooth and ripple-free. Catling, bacon-and-egg breakfast cooked and eaten, nurses a mug of coffee as he pilots the narrowboat through the mean outskirts of Ramsey. And all the time, our channel tightens. There would be no possibility now of another nifty U-turn: passing the marina, we have no choice but to carry on as far as this ditch, the High Lode, will take us. Catling doesn't drive cars, never has (there are women for that), but the slow-moving, go-with-the-drift waterworld of the Middle Level suits him very well. Let it happen, it is inevitable. The narrowboat has the kind of valves, flanges, nozzles and teats that he likes. A firm turn of the key. The engine coughs and obliges.

There are Catlings listed on the census forms at Whittlesey Library, huggers of the river bank: watermen, rooters of vegetables. There were always two sorts of folk on the Middle Level between Nene and Ouse: farmers, jealous of their recently acquired land, and river rats (lightermen, demi-pirates, water gypsies). They fought, bare-knuckled, with sticks and clubs, ferociously. Horses, bred to tow barges and flat-bottomed craft, were no respecters of towpaths. (There were no towpaths until they created them.) The horses were as strong as the men. They learnt to come on and off boats. If necessary, they went into the canals to drag their burdens. They jumped obstructions. When river gangs, hauling corn and malt, arrived at a Fen pub, miles from a village, they drank it dry. It was a famous night for the farmer/publican if they didn't burn the place down. ‘Conspicuous conviviality’ the books call it.

Whittlesey families, servicing the brickworks, using the Mere as a connection between Nene and Ouse, included the Hemmaways, Boons and Gores. Three of the Gores are recorded as attending the funeral of Anna's great-grandfather, William Rose. Among recorded floral tributes, most sent by relatives, is a wreath from ‘Mrs Gore and family’.

The Roses, it appears, lived on the hinge of the dispute between riparian interests and watermen. Their land was always bordered by a canal or a river. Sons picked up property, where and when they could, between Ramsey and Whittlesey. The beer they brewed was drunk by watermen as much as by farm-labourers. They emerged as an established family in the golden century of water transport, 1750–1850, before railways took over. It was a self-reliant, low-church (revised pagan) way of life: women ferrying horses, across learns or drains, by punting with long poles known as ‘quants’. Men scuttling lighters to make improvised dams. Boys healing a breach in the dyke with tarpaulin. Stupendous acts of porterage: the dragging of craft across every natural obstacle. Cargoes carried in bundles on the head. The Roses must have been a strong-necked crowd: wide in the shoulder, bowed in the leg.

Our narrowboat is a forty-six-footer, the Ramsey channel brushes against our ribs. Anna has woken, not surprisingly, with a cracking headache. I can feel the aftermath of the cramp in my calf. But our skipper is jaunty, convinced that we'll find somewhere to moor. And he's right: nobody has attempted it in recent times, but there is an industrial dock, turning space, in a town where industry seems, at best, inactive.

We come ashore, the ground is none too steady; it is still recovering from the shock of emerging from the black waters. The abbey church, for centuries, was a yellow-grey ghost reached by ladders laid over the mud.

Near-rain, a mongrel atmosphere of air and water (for the benefit of those who breathe through their gills), has evolved as Ramsey's microclimate: it sluices you in liquefied stonedust. Energy and heat are sucked from mammals, so that only the most determined pilgrims get away.

To keep up stamina, I buy a loaf in the shape of a wreath; it is so heavy that, used as a life-belt, it would take you straight to the bottom of the river. Catling buys a bottle of whisky, a large one. More corned beef. More everything. Sherry to improve the Bloody Marys. Chops, spring onions. The only way to carry all this stuff to the church, so I decide, is in a bag: a blue plastic laundry bag with very short straps. This, from the Ramsey equivalent of Prada, at £1.99.

The spirit of the town is located, by Catling, in a shop that specialises in reptiles. He's fond of reptiles and used to spend much of his time sending out stick-insects, locusts packed in cotton wool. Lizards, he's fond of those too. So he is delighted to discover a Golden Python from Burma, the pride of Ramsey, its unacknowledged totem and oracle. The beast slumbers in a vast tank, waiting for supplicants with troublesome requests. Its head, so Catling reports, rests in a dog's water bowl. What happened to the dog he doesn't say.

We recognise the grass, the wall; the church, the burial ground. It hasn't changed in the years since we arrived here, on the burn, in search of that elusive ‘key’. ‘Ramsey holds the key.’ (And holds it close to the chest.) But this time we have voyaged, unhurried, by water. We have meditated for many slow hours on our destination: desultory conversation, mixing of Bloody Marys, horizon-chasing. Apart from the clinking laundry-bag burden, I'm ready. It's now or never.

My earlier stupidity, cobwebs over the eyes, was astonishing. All that was required, Anna and Brian holding back, swaying in the porch, not sure if they should return immediately to the boat, was a brisk walk down the north side of the parish church of St Thomas à Becket. A careful reading of stained-glass windows. The answer was so obvious, so literal, we must have been ashamed to recognise it in our hunger for signs and portents. It's not the Ackroydian ‘Resurgam’ on the outside of the south wall of the chancel. Prebendary Robins, who died in 1673, requested that this word/symbol be cut into a stone near his grave. Nor is it the fish-shaped recess above the round-headed lancets on the east wall. Revelation comes with the window in which a yellow-bearded Saxon warrior, out of a superhero comic, is gripping a very large key in his right hand: ‘Gift of the Ailwyn Lodge of Freemasons No. 3535, AD 1912.’ An open book floats between twin Masonic pillars: golden compasses, golden pentacle. The window, dedicated to the memory of James Sanderson Sergeant (20 September 1823-13 April 1882), has been subscribed by a clutch of Masons from St Leonards-on-Sea.

The golden key dangles like an open-ended rebuke. The warrior's left hand crosses his breast. There are wands and tassels: standard elements of mystical geometry. And rich colours: scarlet, green, midnight blue. The shape of the man, in the jigsaw of glass slivers, makes a vertical map. Lead rivers, islands of sand. Whittlesey Mere as a portion of brilliant red cloth.

I can see where the key is, the riddling message, but I have no idea what it means (beyond the path the key seems to indicate, across the graveyard, to a bricked-up door in the abbey wall). I am as dull as ever – until I notice the opposite window, the south wall: St Etheldreda. A tall, handsome woman, big haired Pre-Raphaelite, holds another key: silver against a gold background. The teeth of the original Masonic key are closed, they point to the east. Etheldreda points to the west. She has a crown, a crozier; a model of the church rests on her right hand. Her left hand, crossing the breast, steadies the model. The saint is wrapped in a long scarlet cloak. Red flowers decorate the grass at her slippered feet. They should be roses.

‘The unbelieving husband shall be saved by the believing wife.’ Announces a banner behind Etheldreda's head. Let that be my key. Anna, on our first expedition, was the missing element. The brandishing of phallic toys, keys too clumsy for any lock, has now been countered by a justified sense of place. By the witnessing of my wife: the lost half I have pursued, so blindly, for so many miles. The quarrel of the road has long since been resolved. The Ramsey window is a coloured mirror. My belief in unbelief is tested afresh. My belief in the potency of Anna's memory is confirmed. All those months ago, walking from Stilton to Glinton, I was drawn to try Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles: a warning against genealogical truffling. Alec D'Urberville, with his faked pedigree, has something to say to Tess: ‘The unbelieving husband is sanctified by the wife and the unbelieving wife is sanctified by the husband.’

Etheldreda is the daughter of the chieftain of the East Angles: King Anna. She is honoured, liturgically, as a twice-married virgin. Her first husband died, marriage unconsummated, after three years. Released from the vows of a second marriage, she took the veil: to live in retirement on the Isle of Ely. But the pious Etheldreda is not the woman in the window: a lush artist's model, smothered in flowers, playing her part in a Golden Dawn ritual. Beneath her, a troop of monks and bishops labour with blocks of masonry: the mislaid Ramsey stones returning from the Mere. Flying and drowning, in the suspension of stained glass, are indistinguishable.

The church of St Thomas is thought to have been built as a hospital or gatehouse for the Benedictine Abbey. Its buildings were converted to accommodate pilgrims. Abbey lands, after the Dissolution, were sold to Sir Richard Williams, the great-grandfather of Oliver Cromwell Tumbled stones were used to build or extend Cambridge colleges: Caius, King's, Trinity.

I spoke the word aloud: ‘Caius’. Keys. The connection with Cambridge, Renchi Bicknell's childhood, is reaffirmed. Trips of my own, poetry initiations. Renchi is devouring, so he explains when I visit Glastonbury, a book about visionary journeys: Dark Figures in the Desired Country: Blake's Illustrations to The Pilgrim's Progress by Gerda S. Norvig. Who demonstrates how Blake converts Bunyan's Interpreter into a ‘key figure’. ‘He literally “holds the key”… to the next room of the dream.’ A real key, or bunch of keys, is the pertinent metaphor. The confirmation, I now realise, that we are on the right track, in the right place.

We wander across Abbey Green to the Gatehouse, which is late fifteenth century; an accidental fragment from which the rest must be assumed or invented. A sepulchral figure, thought to be Earl Ailwyn (of stained-glass fame), floats in a cage. He has been granted three-dimensional reality, then starved to essence. The effigy is imprisoned within the ribs of an upturned boat. A hatchet-carved intensity of gaze burns off accidental tourists. Here, Catling acknowledges, is a major item of sculpture: beyond representation, beyond pious devotion. Spirit in stone: angry and vital. The setting is as important as the thing itself. A standing figure laid on its back, caught in a man-trap, placed in a tower with a blind set of stairs. Worn steps leading to another bricked-up doorway.

A circuit of the church grounds, gravestones, memorials, is undertaken, without much conviction, before our return to the river. By now, we appreciate churchyard etiquette, stately pace, soft rain, bare trees; one burial site dissolving into the next. Ramsey is grander than the others, it trades on its association with the church and the walls of the abbey: curtains of trailing willow, well-nourished parasites. Urns with rams' heads, curled horns. Angels with folded arms. Clusters of submerged Roses. Ramsey is the fountainhead of the family. Where one Rose is found, we know, there will be others. We have William, son of Daniel and Ann Rose, who died on 6 October 1842. And another William Rose. We have his wife, Hannah. The Hannah part was botched by the stonemason and had to be recut. Beneath this revision, the earlier attempt is still visible: an obliterated Anna. Beyond the Rose reservation, more obscurely, set against the wall and swallowed in ivy, is a solitary stone. A family connection?

The Christian name, Daniel, can be read without strain, but the date is almost erased – perhaps 1830? The surname, lichen padding the indents of cut letters, is clear enough. A name we have never come across in this country, SINCLAIR.

Was he Jewish, or part-Jewish, this Daniel in the den of Roses? I read everything I can find about fetches, doppelgängers, spectral twins: honouring a misplaced Scottish heritage. I had to track down The Double, a novel by the Portuguese author José Saramago. The plot, with winks at Sterne and Dostoevsky, is playful. A history teacher notices a bit-part actor playing a hotel receptionist in a video. The man has his face. The receding hair, the moustache he wore five years ago, when the film was made. By a tedious process of elimination, labouring through all the other tapes from the production company responsible for the first film, he discovers the name of the actor, his double: Daniel Santa-Clara. Daniel Sinclair. Driven to conclude an insane quest, the history man fixes the jobbing actor's real name: Claro. Clare. The literal translation of Saramago's Portuguese title is ‘The Duplicated Man’.