Havana |

|

HISTORY

ORIENTATION

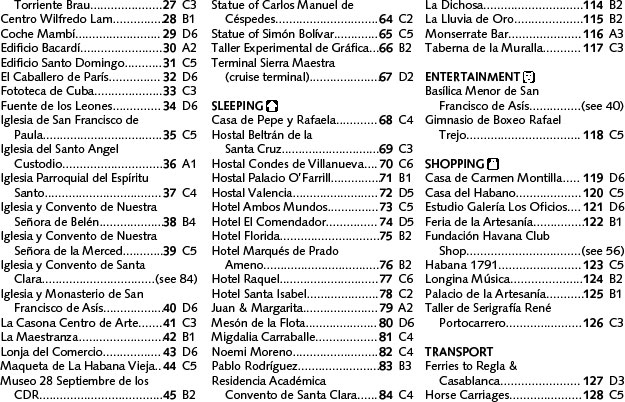

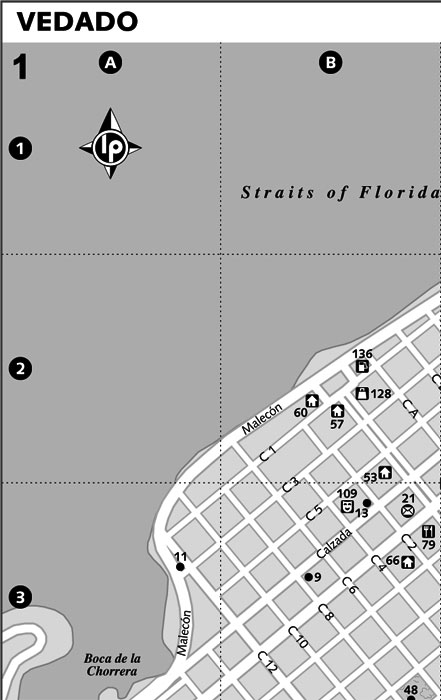

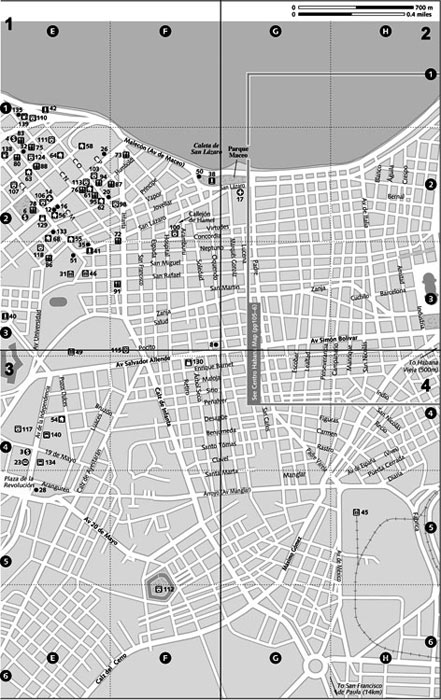

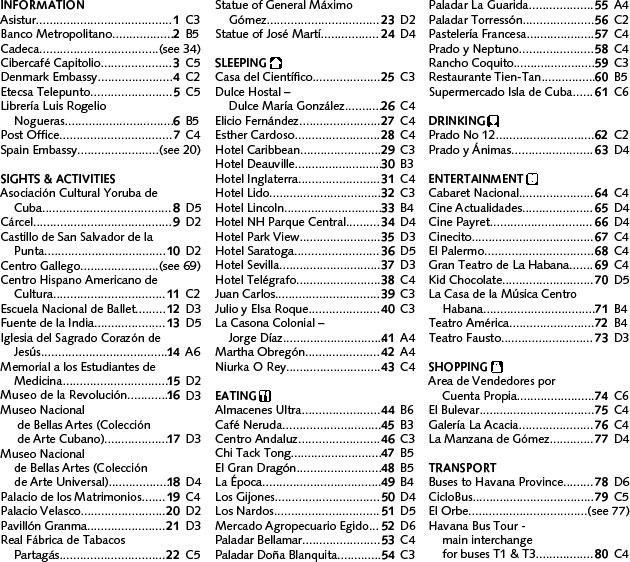

DOWNTOWN HAVANA

INFORMATION

DANGERS & ANNOYANCES

SIGHTS & ACTIVITIES

HABANA VIEJA WALKING TOUR

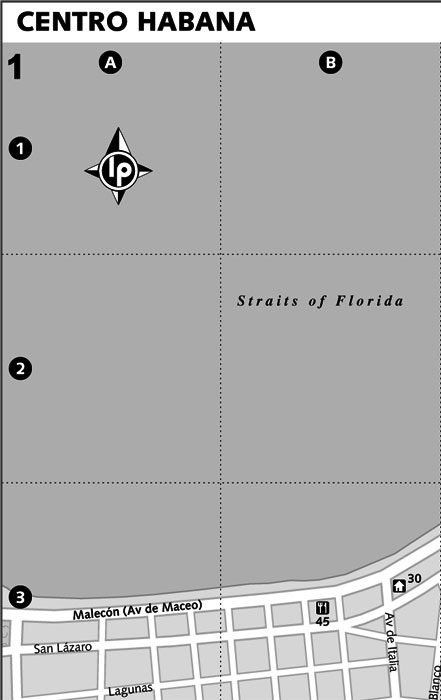

CENTRO HABANA ARCHITECTURAL TOUR

COURSES

HAVANA FOR CHILDREN

TOURS

SLEEPING

EATING

DRINKING

ENTERTAINMENT

SHOPPING

GETTING THERE & AWAY

GETTING AROUND

OUTER HAVANA

PLAYA & MARIANAO

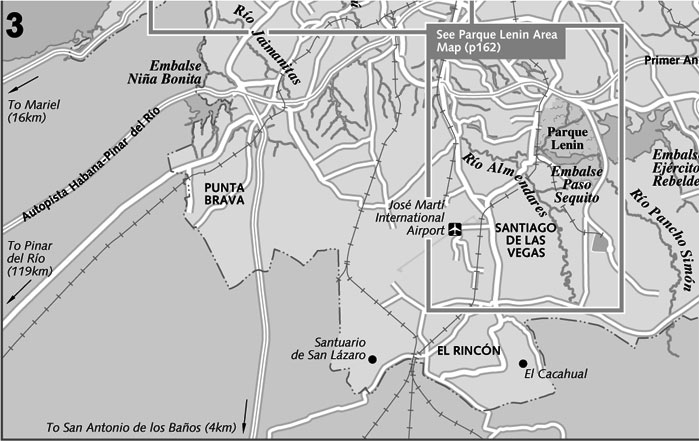

PARQUE LENIN AREA

SANTIAGO DE LAS VEGAS AREA

REGLA

GUANABACOA

SAN FRANCISCO DE PAULA

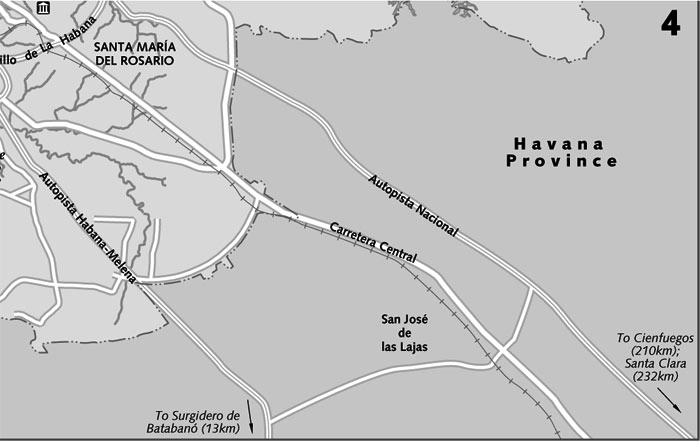

SANTA MARÍA DEL ROSARIO

PARQUE HISTÓRICO MILITAR MORRO-CABAÑA

CASABLANCA

COJÍMAR AREA

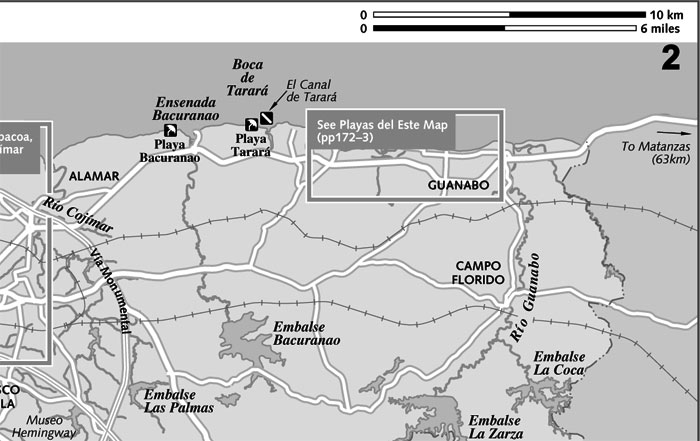

PLAYAS DEL ESTE

‘Anything is possible in Havana,’ wrote British novelist Graham Greene of Cuba’s rhapsodic capital, echoing the thoughts and dreams of millions. Prophetically, he wasn’t far wrong. Truly one of the world’s great urban centers, this tough-minded yet ebullient Caribbean metropolis is a riotous mélange of noble monuments and hip-gyrating music that has few cultural equals.

Yet, scarred by its past and flummoxed by one of the worst economic fallouts of modern times, Havana is no Paris. Here, at the proverbial heart of Cuba’s great paradox, seductive beauty sidles up to spectacular decay, as life carries on precariously and capriciously, but always passionately.

For most visitors, the jewel in Havana’s ruptured crown is Habana Vieja, a fascinating work-in-progress that has taken one of Spain’s most beguiling colonial centers and rehabilitated it after years of poverty and neglect. Winking on the sidelines, a statuesque cluster of historical movers and shakers look down in granite and bronze: heroes and villains, colonizers and independence fighters, sugar merchants and mambo kings, hustlers and dreamers.

Enamored Habaneros love their city and it’s not difficult to see why. This is the metropolis that inspired Lorca and enchanted Hemingway, a place where Winston Churchill wistfully concluded that he could quite happily ‘leave his bones.’ But while the setting is mesmerizing and the history like pungent cigar smoke drifting through the louvers, the city is far more than just a museum to rogues and revolutionaries. At least half of Havana’s attraction is visceral. You’ll fall in love here, but you’ll struggle to ever understand why. The city is an impenetrable muse, the ultimate ‘riddle wrapped up in a mystery inside an enigma.’ Hit the streets and let it work its magic.

Return to beginning of chapter

HISTORY

In 1514 San Cristóbal de la Habana was founded on the south coast of Cuba near the mouth of the Río Mayabeque by Spanish conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez. Named after the daughter of a famous Taíno Indian chief, the city was moved twice during its first five years due to mosquito infestations and wasn’t permanently established on its present site until December 17, 1519. According to local legend, the first Mass was said beneath a ceiba tree in present-day Plaza de Armas.

Havana is the most westerly and isolated of Diego Velázquez’ original villas and life was hard in the early days. Things didn’t get any better in 1538 when French corsairs and local slaves razed the city to the ground.

It took the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Peru to swing the pendulum in Havana’s favor. The town’s strategic location, at the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico, made it a perfect nexus point for the annual treasure fleets to regroup in the sheltered harbor before heading east. Thus endowed, its ascension was quick and decisive, and in 1607 Havana replaced Santiago as the capital of Cuba.

The city was sacked by French privateers led by Jacques de Sores in 1555; the Spanish replied by building the La Punta and El Morro forts between 1558 and 1630 to reinforce an already formidable protective ring. From 1674 to 1740, a strong wall around the city was added. These defenses kept the pirates at bay but proved ineffective when Spain became embroiled in the Seven Years’ War with Britain, the strongest maritime power of the era.

On June 6, 1762, a British army under the Earl of Albemarle attacked Havana, landing at Cojímar and striking inland to Guanabacoa. From there they drove west along the northeastern side of the harbor, and on July 30 they attacked El Morro from the rear. Other troops landed at La Chorrera, west of the city, and by August 13 the Spanish were surrounded and forced to surrender. The British held Havana for 11 months. (The same war cost France almost all its colonies in North America, including Québec and Louisiana – a major paradigm shift.)

When the Spanish regained the city a year later in exchange for Florida, they began a crash building program to upgrade the city’s defenses in order to avoid another debilitating siege. A new fortress, La Cabaña, was built along the ridge from which the British had shelled El Morro, and by the time the work was finished in 1774, Havana had become the most heavily fortified city in the New World, the ‘bulwark of the Indies.’

The British occupation resulted in Spain opening Havana to freer trade. In 1765 the city was granted the right to trade with seven Spanish cities instead of only Cádiz, and from 1818 Havana was allowed to ship its sugar, rum, tobacco and coffee directly to any part of the world. The 19th century was an era of steady progress: first came the railway in 1837, followed by public gas lighting (1848), the telegraph (1851), an urban transport system (1862), telephones (1888) and electric lighting (1890). By 1902 the city, which had been physically untouched by the devastating wars of independence, boasted a quarter of a million inhabitants.

Havana entered the 20th century on the cusp of a new beginning. With the quasi-independence of 1902, the city had expanded rapidly west along the Malecón and into the wooded glades of formerly off-limits Vedado. There was a large influx of rich Americans at the start of the Prohibition era, and the good times began to roll with a healthy (or not-so-healthy) abandon; by the 1950s Havana was a decadent gambling city frolicking to the all-night parties of American mobsters and scooping fortunes into the pockets of various disreputable hoods such as Meyer Lansky.

For Fidel, it was an aberration. On taking power in 1959, the new revolutionary government promptly closed down all the casinos and then sent Lansky and his sycophantic henchmen back to Miami. The once-glittering hotels were divided up to provide homes for the rural poor. Havana’s long decline had begun.

Today the city’s restoration is ongoing and a stoic fight against the odds in a country where shortages are part of everyday life and money for raw materials is scarce. Since 1982 City Historian Eusebio Leal Spengler has been piecing Habana Vieja back together street by street and square by square with the aid of Unesco and a variety of foreign investors. Slowly but surely, the old starlet is starting to rediscover her former greatness.

Return to beginning of chapter

ORIENTATION

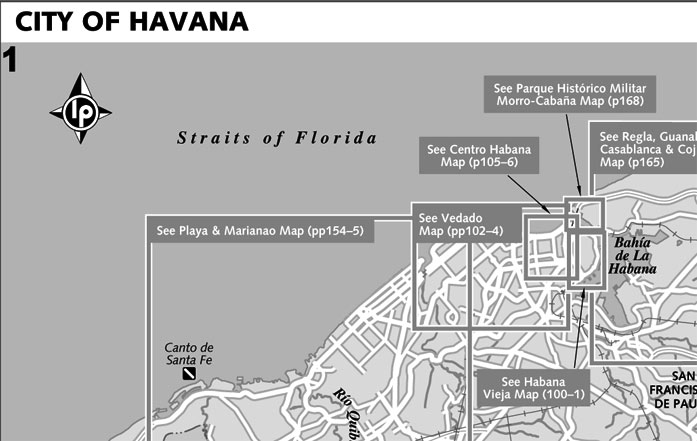

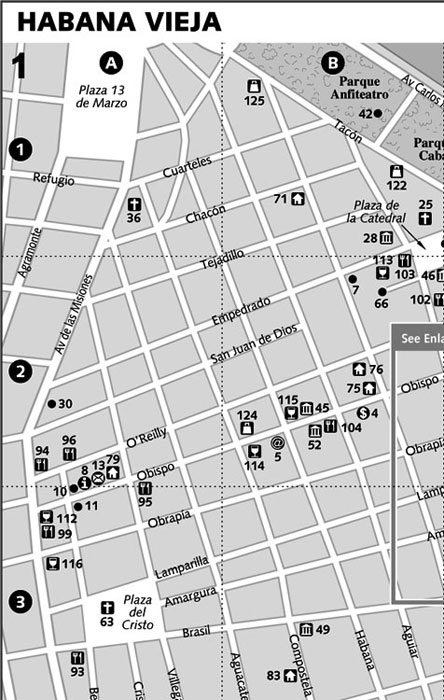

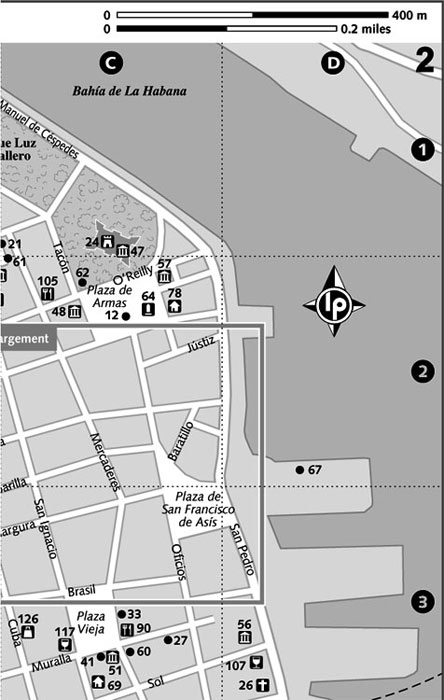

Surrounded by Havana province, the City of Havana is divided into 15 municipalities (Map).

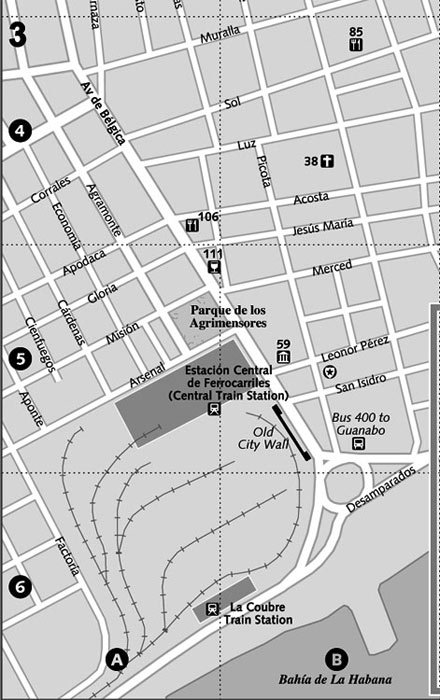

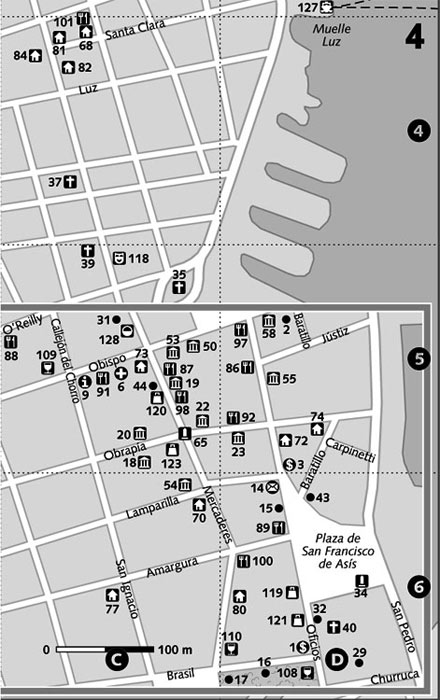

Habana Vieja, sometimes referred to as the Old Town, sits on the western side of the harbor in an area once bounded by 17th-century city walls that ran along present Av de Bélgica and Av de las Misiones. In 1863 these walls were demolished and the city spilled west into Centro Habana, bisected by busy San Rafael (the dividing line between the two is still fuzzy). West of Calzada de Infante lies Vedado, the 20th-century hotel and entertainment district that developed after independence in 1902. Near Plaza de la Revolución and between Vedado and Nuevo Vedado, a huge government complex was erected in the 1950s. West of the Río Almendares are Miramar, Marianao and Playa, Havana’s most fashionable residential suburbs prior to the 1959 Revolution.

Between 1955 and 1958, a 733m-long tunnel was drilled between Habana Vieja and Habana del Este under the harbor mouth, and since 1959 a flurry of ugly high-rise housing blocks have been thrown up in Habana del Este, Cojímar (a former fishing village) and Alamar, northeast of the harbor. South of Habana del Este’s endless blocks of flats are the prettier colonial towns of Guanabacoa, San Francisco de Paula and Santa María del Rosario. On the eastern side of the harbor are Regla and Casablanca.

Totally off the beaten track for most tourists are Havana’s working-class areas south of Centro Habana, including Cerro, Diez de Octubre and San Miguel del Padrón. Further south still is industrial Boyeros, with the golf course, zoo and international airport, and Arroyo Naranjo with Parque Lenin.

Visitors spend the bulk of their time in Habana Vieja, Centro Habana and Vedado. Important streets here include: Obispo, a pedestrian mall cutting through the center of Habana Vieja; Paseo de Martí (aka Paseo del Prado or just ‘Prado’), an elegant 19th-century promenade in Centro Habana; Av de Italia (aka Galiano), Centro Habana’s main shopping street for Cubans; Malecón (aka Av de Maceo), Havana’s broad coastal boulevard; and Calle 23 (aka La Rampa), the heart of Vedado’s commercial district.

Confusingly, many main avenues around Havana have two names in everyday use – a new name that appears on street signs and in this book, and an old name overwhelmingly preferred by locals. See the boxed text on opposite to sort it all out.

Maps

The best place to head for maps is the official government information service, Infotur, which has a wide variety of city maps, many of them free.

Return to beginning of chapter

DOWNTOWN HAVANA

For simplicity’s sake downtown Havana can be split into three main areas: Habana Vieja, Centro Habana and Vedado, which between them contain the bulk of the tourist sights. Centrally located Habana Vieja is the city’s atmospheric historical masterpiece; Centro Habana, to the west, provides an eye-opening look at the real-life Cuba in close-up; while the more majestic Vedado is the once-notorious Mafia-run district replete with hotels, restaurants and a pulsating nightlife.

Return to beginning of chapter

INFORMATION

Bookstores

- Librería Centenario del Apóstol (Map;

870-7220; Calle 25 No 164, Vedado;

870-7220; Calle 25 No 164, Vedado;  10am-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) Great assortment of used books.

10am-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) Great assortment of used books. - Librería Grijalbo Mondadovi (Map; Palacio del Segundo Cabo, O’Reilly No 4, Plaza de Armas, Habana Vieja;

9am-5pm Mon-Sat) Fantastic mix of magazines, guidebooks, reference, politics and art imprints in English and Spanish.

9am-5pm Mon-Sat) Fantastic mix of magazines, guidebooks, reference, politics and art imprints in English and Spanish. - Librería La Internacional (Map;

861-3283; Obispo No 526, Habana Vieja;

861-3283; Obispo No 526, Habana Vieja;  9am-7pm Mon-Sat, 9am-3pm Sun) Good selection of guides, photography books and Cuban literature in English; next door is Librería Cervantes, an antiquarian bookseller.

9am-7pm Mon-Sat, 9am-3pm Sun) Good selection of guides, photography books and Cuban literature in English; next door is Librería Cervantes, an antiquarian bookseller. - Librería Luis Rogelio Nogueras (Map;

863-8101; Av de Italia No 467 btwn Barcelona & San Martín, Centro Habana) Literary magazines and Cuban literature in Spanish.

863-8101; Av de Italia No 467 btwn Barcelona & San Martín, Centro Habana) Literary magazines and Cuban literature in Spanish. - Librería Rayuela (Map; Casa de las Américas, cnr Calles 3 & G, Vedado;

9am-4:30pm Mon-Fri) Great for contemporary literature, compact discs; some guidebooks.

9am-4:30pm Mon-Fri) Great for contemporary literature, compact discs; some guidebooks. - Moderna Poesía (Map;

861-6640; Obispo 525, Habana Vieja;

861-6640; Obispo 525, Habana Vieja;  10am-8pm) Perhaps Havana’s best spot for Spanish-language books.

10am-8pm) Perhaps Havana’s best spot for Spanish-language books. - Plaza de Armas Secondhand Book Market (Map; cnr Obispo & Tacón, Habana Vieja) Old, new and rare books; with plenty of Fidel’s written pontifications.

Cultural Centers

- Alliance Française (Map;

833-3370; Calle G No 407 btwn Calles 17 & 19, Vedado) Free French films Monday (11am), Wednesday (3pm) and Friday (5pm); good place to meet Cubans interested in French culture.

833-3370; Calle G No 407 btwn Calles 17 & 19, Vedado) Free French films Monday (11am), Wednesday (3pm) and Friday (5pm); good place to meet Cubans interested in French culture. - Casa de la Cultura Centro Habana (Map;

878-4727; Av Salvador Allende No 720); Vedado (Map;

878-4727; Av Salvador Allende No 720); Vedado (Map;  831-2023; Calzada No 909) High-quality concerts and festivals.

831-2023; Calzada No 909) High-quality concerts and festivals. - Casa de las Américas (Map;

838-2706; cnr Calles 3 & G, Vedado) Powerhouse of Cuban and Latin American culture, with conferences, exhibitions, a gallery, book launches and concerts. The Casa’s annual literary award is one of the Spanish-speaking world’s most prestigious. Pick up a schedule of weekly events in the library.

838-2706; cnr Calles 3 & G, Vedado) Powerhouse of Cuban and Latin American culture, with conferences, exhibitions, a gallery, book launches and concerts. The Casa’s annual literary award is one of the Spanish-speaking world’s most prestigious. Pick up a schedule of weekly events in the library. - Fundación Alejo Carpentier (Map; Empedrado No 215, Habana Vieja;

8am-4pm Mon-Fri) Near the Plaza de la Catedral. Check for cultural events at this baroque former palace of the Condesa de la Reunión (1820s) where Carpentier set his famous novel El Siglo de las Luces.

8am-4pm Mon-Fri) Near the Plaza de la Catedral. Check for cultural events at this baroque former palace of the Condesa de la Reunión (1820s) where Carpentier set his famous novel El Siglo de las Luces. - Instituto Cubano de Amistad con los Pueblos (ICAP; Map;

830-3114; Paseo No 416 btwn Calles 17 & 19, Vedado;

830-3114; Paseo No 416 btwn Calles 17 & 19, Vedado;  11am-11pm) Rocking cultural and musical events in elegant mansion (1926); restaurant, bar and cigar shop also here.

11am-11pm) Rocking cultural and musical events in elegant mansion (1926); restaurant, bar and cigar shop also here. - Union Nacional de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (Uneac; Map;

832-4551; cnr Calles 17 & H, Vedado) The pulse of the Cuban arts scene, this place is the first point of call for anyone with more than a passing interest in poetry, literature, art and music.

832-4551; cnr Calles 17 & H, Vedado) The pulse of the Cuban arts scene, this place is the first point of call for anyone with more than a passing interest in poetry, literature, art and music.

Emergency

- Asistur (Map;

886-8339, 866-8920; asisten@asistur.cu; www.asistur.cu; Paseo de Martí No 208, Centro Habana;

886-8339, 866-8920; asisten@asistur.cu; www.asistur.cu; Paseo de Martí No 208, Centro Habana;  8:30am-5:30pm Mon-Fri, 8am-2pm Sat) Someone on staff should speak English; the alarm center here is open 24 hours.

8:30am-5:30pm Mon-Fri, 8am-2pm Sat) Someone on staff should speak English; the alarm center here is open 24 hours. - Fire Service (

105)

105) - Police (

106)

106)

Internet Access

Havana doesn’t have any private internet cafes. Your best bet outside the Etecsa Telepuntos is in the posher hotels. Most Habaguanex hotels in Habana Vieja have internet terminals and sell scratch cards (CUC$6 per hour) that work throughout the chain. You don’t have to be a guest to use them.

- Cibercafé Capitolio (Map;

862-0485; cnr Paseo de Martí & Brasil, Centro Habana; per hr CUC$5;

862-0485; cnr Paseo de Martí & Brasil, Centro Habana; per hr CUC$5;  8am-8pm) Inside main entrance.

8am-8pm) Inside main entrance. - Etecsa Telepuntos Centro Habana (Map; Aguilar No 565;

8am-9:30pm) The long-promised internet terminals still hadn’t arrived at time of writing; check ahead; Habana Vieja (Map; Habana 406) Six terminals in a back room.

8am-9:30pm) The long-promised internet terminals still hadn’t arrived at time of writing; check ahead; Habana Vieja (Map; Habana 406) Six terminals in a back room. - Hotel Business Centers Hotel Habana Libre (Map; Calle L btwn Calles 23 & 25, Vedado); Hotel Inglaterra (Map; Paseo de Martí No 416, Centro Habana); Hotel Nacional (Map; cnr Calles O & 21, Vedado); Hotel NH Parque Central (Map; btwn Agramonte & Paseo de Martí, Centro Habana) Costs vary at these places.

Libraries

Foreign students with a carnet (or letter from their academic institution) can get library cards. Each library requires its own card; show up with two passport photos.

- Biblioteca José A Echeverría (Map;

838-2705; Casa de las Américas, Calle G No 210, Vedado) Best art, architecture and general-culture collection; books can’t leave library.

838-2705; Casa de las Américas, Calle G No 210, Vedado) Best art, architecture and general-culture collection; books can’t leave library. - Biblioteca Nacional José Martí (Map;

881-7657; cnr Paseo & Av de la Independencia, Plaza de la Revolución, Vedado;

881-7657; cnr Paseo & Av de la Independencia, Plaza de la Revolución, Vedado;  8:30am-6pm Mon-Sat) Havana’s biggest library. Book and magazine launches are often held here.

8:30am-6pm Mon-Sat) Havana’s biggest library. Book and magazine launches are often held here. - Biblioteca Rubén M Villena (Map;

862-9035; Obispo No 59 cnr Baratillo, Habana Vieja;

862-9035; Obispo No 59 cnr Baratillo, Habana Vieja;  8am-9pm Mon-Sat, 9am-4pm Sat) Nice reading rooms and garden.

8am-9pm Mon-Sat, 9am-4pm Sat) Nice reading rooms and garden.

Media

Cuba has a fantastic radio culture, where you’ll hear everything from salsa to Supertramp, plus live sports broadcasts and soap operas. Radio is also the best source for listings on concerts, plays, movies and dances.

HABANA VIEJA

VEDADO (p102-3)

CENTRO HABANA Click here

- Radio Ciudad de la Habana (820AM & 94.9FM) Cuban tunes by day, foreign pop at night; great ‘70s flashback at 8pm on Thursday and Friday.

- Radio Metropolitana (910AM & 98.3FM) Jazz and traditional boleros (music in 3/4 time); excellent Sunday afternoon rock show.

- Radio Musical Nacional (590AM & 99.1FM) Classical.

- Radio Progreso (640AM & 90.3 FM) Soap operas and humor.

- Radio Rebelde (640AM, 710AM & 96.7FM) News, interviews, good mixed music, plus baseball games.

- Radio Reloj (950AM & 101.5FM) News, plus the time every minute of every day.

- Radio Taíno (1290AM & 93.3FM) National tourism station with music, listings and interviews in Spanish and English. Nightly broadcasts (5pm to 7pm) list what’s happening around town.

Medical Services

Most of Cuba’s specialist hospitals offering services to foreigners are based in Havana; see www.cubanacan.cu for details. Consult the Playa & Marianao section of this chapter Click here for other international clinics and pharmacies.

- Centro Oftalmológico Camilo Cienfuegos (Map;

832-5554; cnr Calle L No 151 & Calle 13, Vedado) Head straight here with eye problems; also has an excellent pharmacy.

832-5554; cnr Calle L No 151 & Calle 13, Vedado) Head straight here with eye problems; also has an excellent pharmacy. - Farmacia Homopática (Map; cnr Calles 23 & M, Vedado;

8am-8pm Mon-Fri, 8am-4pm Sat)

8am-8pm Mon-Fri, 8am-4pm Sat) - Farmacia Taquechel (Map;

862-9286; Obispo No 155, Habana Vieja;

862-9286; Obispo No 155, Habana Vieja;  9am-6pm) Next to the Hotel Ambos Mundos. Cuban wonder drugs such as anticholesterol medication PPG sold in pesos here.

9am-6pm) Next to the Hotel Ambos Mundos. Cuban wonder drugs such as anticholesterol medication PPG sold in pesos here. - Hospital Nacional Hermanos Ameijeiras (Map;

877-6053; San Lázaro No 701, Centro Habana) Special hard-currency services, general consultations and hospitalization. Enter via the lower level below the parking lot off Padre Varela (ask for CEDA in Section N).

877-6053; San Lázaro No 701, Centro Habana) Special hard-currency services, general consultations and hospitalization. Enter via the lower level below the parking lot off Padre Varela (ask for CEDA in Section N). - Hotel Pharmacies Hotel Habana Libre (Map;

831-9538; Calle L btwn Calles 23 & 25, Vedado) Products sold in Convertibles; Hotel Sevilla (Map;

831-9538; Calle L btwn Calles 23 & 25, Vedado) Products sold in Convertibles; Hotel Sevilla (Map;  861-5703; Prado cnr Trocadero, Habana Vieja)

861-5703; Prado cnr Trocadero, Habana Vieja)

Money

- Banco de Crédito y Comercio Vedado (Map; cnr Línea & Paseo); Vedado (Map;

870-2684; Airline Bldg, Calle 23); Vedado (Map;

870-2684; Airline Bldg, Calle 23); Vedado (Map;  879-2074; Av Independencia No 101) The last one – in post office between Terminal de Ómnibus and Plaza de la Revolución – is most convenient to immigration for visa extension stamps. Expect lines.

879-2074; Av Independencia No 101) The last one – in post office between Terminal de Ómnibus and Plaza de la Revolución – is most convenient to immigration for visa extension stamps. Expect lines. - Banco Financiero Internacional Habana Vieja (Map;

860-9369; cnr Oficios & Brasil); Vedado (Map; Hotel Habana Libre, Calle L btwn Calles 23 & 25)

860-9369; cnr Oficios & Brasil); Vedado (Map; Hotel Habana Libre, Calle L btwn Calles 23 & 25) - Banco Metropolitano Centro Habana (Map;

862-6523; Av de Italia No 452 cnr San Martín); Vedado (Map;

862-6523; Av de Italia No 452 cnr San Martín); Vedado (Map;  832-2006; cnr Línea & Calle M, Vedado)

832-2006; cnr Línea & Calle M, Vedado) - Cadeca Centro Habana (Map; cnr Neptuno & Agramonte;

9am-noon & 1-7pm Mon-Sat); Habana Vieja (Map; cnr Oficios & Lamparilla;

9am-noon & 1-7pm Mon-Sat); Habana Vieja (Map; cnr Oficios & Lamparilla;  8am-7pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun); Vedado (Map; Calle 23 btwn Calles K & L;

8am-7pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun); Vedado (Map; Calle 23 btwn Calles K & L;  7am-2:30pm & 3:30-10pm); Vedado (Map; Mercado Agropecuario, Calle 19 btwn Calles A & B;

7am-2:30pm & 3:30-10pm); Vedado (Map; Mercado Agropecuario, Calle 19 btwn Calles A & B;  7am-6pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun); Vedado (Map; cnr Malecón & Calle D) Cadeca gives cash advances and changes traveler’s checks at 3.5% commission Monday to Friday (4% weekends).

7am-6pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun); Vedado (Map; cnr Malecón & Calle D) Cadeca gives cash advances and changes traveler’s checks at 3.5% commission Monday to Friday (4% weekends). - Cambio (Map; Obispo No 257, Habana Vieja;

8am-10pm) The best opening hours in town.

8am-10pm) The best opening hours in town.

Post

- DHL Vedado (Map;

832-2112; Calzada No 818 btwn Calles 2 & 4;

832-2112; Calzada No 818 btwn Calles 2 & 4;  8am-5pm Mon-Fri); Vedado (Map;

8am-5pm Mon-Fri); Vedado (Map;  836-3564; Hotel Nacional, cnr Calles O & 21)

836-3564; Hotel Nacional, cnr Calles O & 21) - Post offices Centro Habana (Map; Gran Teatro, cnr San Martín & Paseo de Martí); Habana Vieja (Map; Plaza de San Francisco de Asís, Oficios No 102); Habana Vieja (Map; Unidad de Filatelía, Obispo No 518;

9am-7pm); Vedado (Map; cnr Línea & Paseo;

9am-7pm); Vedado (Map; cnr Línea & Paseo;  8am-8pm Mon-Sat); Vedado (Map; cnr Calles 23 & C;

8am-8pm Mon-Sat); Vedado (Map; cnr Calles 23 & C;  8am-6pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sat); Vedado (Map; Av de la Independencia btwn Plaza de la Revolución & Terminal de Ómnibus;

8am-6pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sat); Vedado (Map; Av de la Independencia btwn Plaza de la Revolución & Terminal de Ómnibus;  stamp sales 24hr) The last one has many services, including photo developing, a bank and Cadeca. The Museo Postal Cubano (

stamp sales 24hr) The last one has many services, including photo developing, a bank and Cadeca. The Museo Postal Cubano ( 870-5581; admission CUC$1;

870-5581; admission CUC$1;  10am-5pm Sat & Sun) here has a philatelic shop. The post office at Obispo, Habana Vieja, also has stamps for collectors.

10am-5pm Sat & Sun) here has a philatelic shop. The post office at Obispo, Habana Vieja, also has stamps for collectors.

Telephone

- Etecsa Telepuntos Centro Habana (Map; Aguilar No 565;

8am-9:30pm) There’s also a Museo de las Telecomunicaciones (

8am-9:30pm) There’s also a Museo de las Telecomunicaciones ( 9am-6pm Tue-Sat) here if you get bored waiting; Habana Vieja (Map; Habana 406)

9am-6pm Tue-Sat) here if you get bored waiting; Habana Vieja (Map; Habana 406)

Toilets

Not overendowed with clean available public toilets, most tourists slip into the upscale hotels if they’re caught short. The following establishments are all fairly relaxed about toilet security.

- Hotel Ambos Mundos (Map; Obispo No 153, Habana Vieja) Tip the attendant.

- Hotel Habana Libre (Map; Calle L btwn Calles 23 & 25, Vedado) To the left of the elevators.

- Hotel Nacional (Map; cnr Calles O & 21, Vedado) Right in the lobby and left past the elevators.

- Hotel Sevilla (Map;Trocadero No 55 btwn Paseo de Martí & Agramonte, Centro Habana) Turn right inside the lobby.

Tourist Information

- Infotur Airport (off Map;

642-6101; Terminal 3 Aeropuerto Internacional José Martí;

642-6101; Terminal 3 Aeropuerto Internacional José Martí;  24hr); Habana Vieja (Map;

24hr); Habana Vieja (Map;  866-3333; Obispo btwn Bernaza & Villegas); Habana Vieja (Map;

866-3333; Obispo btwn Bernaza & Villegas); Habana Vieja (Map;  863-6884; cnr Obispo & San Ignacio;

863-6884; cnr Obispo & San Ignacio;  10am-1pm & 2-7pm) Books excursions, sells maps, phone cards and transport schedules.

10am-1pm & 2-7pm) Books excursions, sells maps, phone cards and transport schedules.

Travel Agencies

Many of the following agencies also have offices at the airport, in the international arrivals lounge of Terminal 3.

- Cubamar Viajes (Map;

833-2523/4; www.cubamarviajes.cu; Calle 3 btwn Calle 12 & Malecón, Vedado;

833-2523/4; www.cubamarviajes.cu; Calle 3 btwn Calle 12 & Malecón, Vedado;  8:30am-5pm Mon-Sat) Travel agency for Campismo Popular cabins countrywide. Also rents mobile homes.

8:30am-5pm Mon-Sat) Travel agency for Campismo Popular cabins countrywide. Also rents mobile homes. - Cubanacán (Map;

873-2686; www.cubanacan.cu; Hotel Nacional, cnr Calles O & 21, Vedado;

873-2686; www.cubanacan.cu; Hotel Nacional, cnr Calles O & 21, Vedado;  8am-7pm) Very helpful; head here if you want to arrange fishing or diving at Marina Hemingway; also in Hotel NH Parque Central, Hotel Inglaterra and Hotel Habana Libre.

8am-7pm) Very helpful; head here if you want to arrange fishing or diving at Marina Hemingway; also in Hotel NH Parque Central, Hotel Inglaterra and Hotel Habana Libre. - Cubatur (Map;

835-4155; cnr Calles 23 & M, Vedado;

835-4155; cnr Calles 23 & M, Vedado;  8am-8pm) Below Hotel Habana Libre. This agency pulls a lot of weight and finds rooms where others can’t, which goes a long way toward explaining its slacker attitude. It has desks offices in most of the main hotels.

8am-8pm) Below Hotel Habana Libre. This agency pulls a lot of weight and finds rooms where others can’t, which goes a long way toward explaining its slacker attitude. It has desks offices in most of the main hotels. - Havanatur (Map;

835-3720; www.havanatur.cu; Calle 23 cnr M, Vedado)

835-3720; www.havanatur.cu; Calle 23 cnr M, Vedado) - San Cristóbal Agencia de Viajes (Map;

861-9171/2; www.viajessancristobal.cu; Oficios No 110 btwn Lamparilla & Amargura, Habana Vieja;

861-9171/2; www.viajessancristobal.cu; Oficios No 110 btwn Lamparilla & Amargura, Habana Vieja;  8:30am-5:30pm Mon-Fri, 8:30am-2pm Sat, 9am-noon Sun) Habaguanex agency operates Habana Vieja’s classic hotels; income helps finance restoration. It offers the best tours in Havana.

8:30am-5:30pm Mon-Fri, 8:30am-2pm Sat, 9am-noon Sun) Habaguanex agency operates Habana Vieja’s classic hotels; income helps finance restoration. It offers the best tours in Havana. - Sol y Son (Map;

833-3647; Calle 23 No 64;

833-3647; Calle 23 No 64;  8:30am-7pm Mon-Fri, 8:30am-noon Sat) Sells Cubana flights.

8:30am-7pm Mon-Fri, 8:30am-noon Sat) Sells Cubana flights.

Return to beginning of chapter

DANGERS & ANNOYANCES

Havana is not a dangerous city, especially when compared to other metropolitan areas in North and South America. There is almost no gun crime, violent robbery, organized gang culture, teenage delinquency, drugs, or dangerous no-go zones. Rather, a heavy police presence on the streets and stiff prison sentences for crimes such as assault have acted as a major deterrent for would-be criminals and kept the dirty tentacles of organized crime at bay.

But it’s not all love and peace, man. Petty crime against tourists in Havana – almost nonexistent in the 1990s – is widespread and on the rise, with pickpocketing, bag-snatching by youths mounted on bicycles and the occasional face-to-face mugging all being reported.

Bring a money belt and keep it on you at all times, making sure that you wear it concealed – and tightly secured – around your waist.

In hotels use a safety deposit box (if there is one) and never leave money/passports/credit cards lying around during the day. Theft from hotel rooms is tediously common, with the temptation of earning three times your monthly salary in one fell swoop often too hard to resist.

In bars and restaurants it is wise to check your change. Purposeful overcharging, especially when someone is mildly inebriated, is a favorite (and easy) trick.

Visitors from the well-ordered countries of Europe or litigation-obsessed North America should keep an eye out for crumbling sidewalks, manholes with no covers, inexplicable driving rules, veering cyclists, carelessly lobbed front-door keys (in Centro Habana) and enthusiastically hit baseballs (almost everywhere). Waves cascading over the Malecón sea wall might look pretty, but the resulting slime-fest has been known to throw Lonely Planet–wielding tourists flying unceremoniously onto their asses.

For more popular scams see the boxed text on Click here.

Return to beginning of chapter

SIGHTS & ACTIVITIES

Habana Vieja

Studded with architectural jewels from every era, Habana Vieja offers visitors one of the finest collections of urban edifices in the Americas. At a conservative estimate, the Old Town alone contains over 900 buildings of historical importance with myriad examples of illustrious architecture ranging from intricate baroque to glitzy art deco.

For a whistle-stop introduction to the best parts of the neighborhood, check out the suggested walking tour Click here or stick closely to the four main squares – Plaza de Armas, Plaza Vieja, Plaza de San Francisco de Asís and Plaza de la Catedral.

The renovation of Habana Vieja is overseen by the government-run agency Habaguanex and directed by long-standing City Historian, Eusebio Leal Spengler. Eager to recreate a ‘living’ historic center that integrates the neighborhood’s 70,000-plus inhabitants, Habaguanex splits its US$160 million annual tourist income between further restoration (45%) and other deserving social projects in the city (55%).

PLAZA DE LA CATEDRAL

Habana Vieja’s most uniform square is a museum to Cuban baroque with all the surrounding buildings (including the city’s magnificent cathedral) dating from the 1700s. Despite this homogeneity, it is actually the newest of the four squares in the Old Town with its present layout dating from the 18th century.

Dominated by two unequal towers and framed by a theatrical baroque facade designed by Italian architect Francesco Borromini, the graceful Catedral de San Cristóbal de La Habana (cnr San Ignacio & Empedrado;  before noon) was described by novelist Alejo Carpentier as ‘music set in stone.’ The Jesuits began construction of the church in 1748 and work continued despite their expulsion in 1767. When the building was finished in 1787, the diocese of Havana was created and the church became a cathedral – one of the oldest in the Americas. The remains of Columbus were interred here from 1795 to 1898 when they were moved to Seville. The best time to visit is during Sunday Mass (10:30am).

before noon) was described by novelist Alejo Carpentier as ‘music set in stone.’ The Jesuits began construction of the church in 1748 and work continued despite their expulsion in 1767. When the building was finished in 1787, the diocese of Havana was created and the church became a cathedral – one of the oldest in the Americas. The remains of Columbus were interred here from 1795 to 1898 when they were moved to Seville. The best time to visit is during Sunday Mass (10:30am).

On the corner to the left of the cathedral is the Centro Wilfredo Lam ( 862-2611; cnr San Ignacio & Empedrado; admission CUC$3;

862-2611; cnr San Ignacio & Empedrado; admission CUC$3;  10am-5pm Mon-Sat), a cafe and exhibition center named after the island’s most celebrated painter but which usually displays the works of more modern painters.

10am-5pm Mon-Sat), a cafe and exhibition center named after the island’s most celebrated painter but which usually displays the works of more modern painters.

Situated on the western side of the Plaza is the majestic Palacio de los Marqueses de Aguas Claras (San Ignacio No 54), a one-time baroque palace completed in 1760 and widely lauded for the beauty of its shady Andalucian patio. Today it houses the Restaurante El Patio.

Directly opposite are the Casa de Lombillo and the Palacio del Marqués de Arcos. The former, built in 1741, once served as a post office (a stone-mask ornamental mailbox built into the wall is still in use). Since 2000 it has functioned as the main office for the City Historian, Eusebio Leal Spengler.

The square’s southern aspect is taken up by its oldest building, the resplendent Palacio de los Condes de Casa Bayona built in 1720. Today it functions as the Museo de Arte Colonial ( 862-6440; San Ignacio No 61; unguided/guided CUC$2/3, camera CUC$2;

862-6440; San Ignacio No 61; unguided/guided CUC$2/3, camera CUC$2;  9am-6:30pm), a small museum displaying colonial furniture and decorative arts. Among the finer exhibits are pieces of china with scenes of colonial Cuba, a collection of ornamental flowers, and many colonial-era dining room sets.

9am-6:30pm), a small museum displaying colonial furniture and decorative arts. Among the finer exhibits are pieces of china with scenes of colonial Cuba, a collection of ornamental flowers, and many colonial-era dining room sets.

At the end of a short cul-de-sac, the Taller Experimental de Gráfica ( 862-0979; Callejón del Chorro No 6; admission free;

862-0979; Callejón del Chorro No 6; admission free;  10am-4pm Mon-Fri) is Havana’s most cutting-edge art workshop, which offers the possibility of engraving classes (Click here).

10am-4pm Mon-Fri) is Havana’s most cutting-edge art workshop, which offers the possibility of engraving classes (Click here).

PLAZA DE ARMAS

Havana’s oldest square was laid out in the early 1520s, soon after the city’s foundation, and was originally known as Plaza de Iglesia after a church – the Parroquial Mayor – that once stood on the site of the present-day Palacio de los Capitanes Generales. The name Plaza de Armas (Square of Arms) wasn’t adopted until the late 16th century, when the colonial governor, then housed in the Castillo de la Real Fuerza, used the site to conduct military exercises. The modern plaza, along with most of the buildings around it, dates from the late 1700s.

In the center of the square, which is lined with royal palms and enlivened by a daily (except Sundays) secondhand book market, is a marble statue of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (1955), the man who set Cuba on the road to independence in 1868.

Filling the whole west side of the Plaza is the Palacio de los Capitanes Generales dating from the 1770s. Built on the site of Havana’s original church, this muscular baroque beauty has served many purposes over the years. From 1791 until 1898 it was the residence of the Spanish captains general. From 1899 until 1902, the US military governors were based here, and during the first two decades of the 20th century the building briefly became the presidential palace. Since 1968 it has been home to the Museo de la Ciudad ( 861-6130; Tacón No 1; unguided/guided CUC$3/4, camera CUC$2;

861-6130; Tacón No 1; unguided/guided CUC$3/4, camera CUC$2;  9am-6pm), one of Havana’s most comprehensive and interesting museums that wraps its way regally around a splendid central courtyard adorned with a white marble statue of Christopher Columbus (1862). Artifacts include period furniture, military uniforms and old-fashioned 19th-century horse carriages, while old photos vividly recreate events from Havana’s rich history such as the 1898 sinking of US battleship Maine in the harbor. It’s better to body-swerve the pushy attendants and wander around at your own pace.

9am-6pm), one of Havana’s most comprehensive and interesting museums that wraps its way regally around a splendid central courtyard adorned with a white marble statue of Christopher Columbus (1862). Artifacts include period furniture, military uniforms and old-fashioned 19th-century horse carriages, while old photos vividly recreate events from Havana’s rich history such as the 1898 sinking of US battleship Maine in the harbor. It’s better to body-swerve the pushy attendants and wander around at your own pace.

Wedged into the square’s northwest corner is the Palacio del Segundo Cabo (O’Reilly No 4; admission CUC$1), constructed in 1772 as the headquarters of the Spanish vice-governor. After several reincarnations as a post office, palace of the Senate, Supreme Court, the National Academy of Arts and Letters, and the seat of the Cuban Geographical Society, the building is today a well-stocked bookstore Click here. Pop-art fans should take a look at the Sala Galería Raúl Martínez ( 9am-6pm Mon-Sat).

9am-6pm Mon-Sat).

On the square’s seaward side is the Castillo de la Real Fuerza, the oldest existing fort in the Americas, built between 1558 and 1577 on the site of an earlier fort destroyed by French privateers in 1555. The west tower is crowned by a copy of a famous bronze weather vane called La Giraldilla; the original was cast in Havana in 1632 by Jerónimo Martínez Pinzón and is popularly believed to be of Doña Inés de Bobadilla, the wife of gold explorer Hernando de Soto. It is now kept in the Museo de la Ciudad, and the figure also appears on the Havana Club rum label. Imposing and indomitable, the castle is ringed by an impressive moat and today shelters the Museo de la Cerámica Artística Cubana ( 861-6130; admission CUC$2;

861-6130; admission CUC$2;  9am-6pm), displaying work by some of Cuba’s leading artists.

9am-6pm), displaying work by some of Cuba’s leading artists.

The tiny neoclassical Doric chapel on the east side of the Plaza, known as the Museo El Templete (admission CUC$2;  8:30am-6pm), was erected in 1828 at the point where Havana’s first Mass was held beneath a ceiba tree in November 1519. A similar ceiba tree has now replaced the original. Inside the chapel are three large paintings of the event by the French painter Jean Baptiste Vermay (1786–1833).

8:30am-6pm), was erected in 1828 at the point where Havana’s first Mass was held beneath a ceiba tree in November 1519. A similar ceiba tree has now replaced the original. Inside the chapel are three large paintings of the event by the French painter Jean Baptiste Vermay (1786–1833).

Adjacent to El Templete is the late-18th-century Palacio de los Condes de Santovenia, today the five-star, 27-room Hotel Santa Isabel. Nearby is the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural ( 863-9361; Obispo No 61; admission CUC$3;

863-9361; Obispo No 61; admission CUC$3;  9:30am-7pm Tue-Sun), which contains examples of Cuba’s flora and fauna.

9:30am-7pm Tue-Sun), which contains examples of Cuba’s flora and fauna.

You’d think that the last thing Havana would need is a car museum, but a block down Calle Oficios lies the small, surreal Museo del Automóvil (Oficios No 13; admission CUC$1;  9am-7pm) stuffed with ancient Thunderbirds, Pontiacs and Ford Model Ts, at least half of which appear to be in better shape than the antiquated automobiles that ply the streets outside.

9am-7pm) stuffed with ancient Thunderbirds, Pontiacs and Ford Model Ts, at least half of which appear to be in better shape than the antiquated automobiles that ply the streets outside.

ALONG MERCADERES & OBRAPíA

Cobbled, car-free Calle Mercaderes (literally: Merchant’s Street) has been fully restored to replicate the splendor of its 18th-century high-water mark. Myriad museums along here include the Casa de Asia ( 863-9740; Mercaderes No 111; admission free;

863-9740; Mercaderes No 111; admission free;  10am-6pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun), with paintings and sculpture from China and Japan; and the Museo de Tabaco (

10am-6pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun), with paintings and sculpture from China and Japan; and the Museo de Tabaco ( 861-5795; Mercaderes No 120; admission free;

861-5795; Mercaderes No 120; admission free;  10am-5pm Mon-Sat), where you can gawp at various indigenous pipes and idols and buy some splendid smokes.

10am-5pm Mon-Sat), where you can gawp at various indigenous pipes and idols and buy some splendid smokes.

The Maqueta de La Habana Vieja (Mercaderes No 114; unguided/guided CUC$1/2;  9am-6pm) is a 1:500 scale model of Habana Vieja complete with an authentic soundtrack meant to replicate a day in the life of the city. It’s incredibly detailed and provides an excellent way of geographically acquainting yourself with the city’s historical core. Come here first.

9am-6pm) is a 1:500 scale model of Habana Vieja complete with an authentic soundtrack meant to replicate a day in the life of the city. It’s incredibly detailed and provides an excellent way of geographically acquainting yourself with the city’s historical core. Come here first.

A few doors down, the Casa de la Obra Pía (Obrapía No 158; admission CUC$1, camera CUC$2; 9am-4:30pm Tue-Sat, 9:30am-12:30pm Sun) is a typical Havana aristocratic residence originally built in 1665 and rebuilt in 1780. Baroque decoration – including an intricate portico made in Cádiz, Spain – covers the exterior facade. In addition to its historical value, the house today also contains one of the City Historian’s most commendable social projects, a sewing and needlecraft cooperative that has a workshop inside and a small shop selling clothes and textiles on Calle Mercaderes. Across the street, the Casa de África (

9am-4:30pm Tue-Sat, 9:30am-12:30pm Sun) is a typical Havana aristocratic residence originally built in 1665 and rebuilt in 1780. Baroque decoration – including an intricate portico made in Cádiz, Spain – covers the exterior facade. In addition to its historical value, the house today also contains one of the City Historian’s most commendable social projects, a sewing and needlecraft cooperative that has a workshop inside and a small shop selling clothes and textiles on Calle Mercaderes. Across the street, the Casa de África ( 861-5798; Obrapía No 157; admission CUC$2;

861-5798; Obrapía No 157; admission CUC$2;  9:30am-7:30pm) houses sacred objects relating to Santería collected by ethnographer Fernando Ortíz.

9:30am-7:30pm) houses sacred objects relating to Santería collected by ethnographer Fernando Ortíz.

The corner of Mercaderes and Obrapía has an international flavor with a bronze statue of Simón Bolívar, the Latin America liberator, and a museum ( 861-3988; Mercaderes No 160; donations accepted;

861-3988; Mercaderes No 160; donations accepted;  9am-5pm Tue-Sun) dedicated to his life across the street. The Casa de México Benito Juárez (

9am-5pm Tue-Sun) dedicated to his life across the street. The Casa de México Benito Juárez ( 861-8166; Obrapía No 116; admission CUC$1;

861-8166; Obrapía No 116; admission CUC$1;  10:15am-5:45pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) exhibits Mexican folk art and plenty of books, but not a lot on Señor Juárez (Mexico’s first indigenous president) himself. Just east is the Casa Oswaldo Guayasamín (

10:15am-5:45pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) exhibits Mexican folk art and plenty of books, but not a lot on Señor Juárez (Mexico’s first indigenous president) himself. Just east is the Casa Oswaldo Guayasamín ( 861-3843; Obrapía No 111; donations accepted;

861-3843; Obrapía No 111; donations accepted;  9am-2:30pm Tue-Sun), the old studio and now a museum of the great Ecuadorian artist who painted Fidel in numerous poses.

9am-2:30pm Tue-Sun), the old studio and now a museum of the great Ecuadorian artist who painted Fidel in numerous poses.

PLAZA DE SAN FRANCISCO DE ASíS

Facing Havana harbor, the breezy Plaza de San Francisco de Asís first grew up in the 16th century when Spanish galleons stopped by at the quayside on their passage through the Indies to Spain. A market took root in the 1500s followed by a church in 1608, though when the pious monks complained of too much noise the market was moved a few blocks south to Plaza Vieja. The Plaza de San Francisco underwent a full restoration in the late 1990s and is most notable for its uneven cobbles and the white marble Fuente de los Leones (Fountain of Lions) carved by the Italian sculptor Giuseppe Gaginni in 1836. A more modern statue outside the square’s famous church depicts El Caballero de París, a well-known street person who roamed Havana during the 1950s, engaging passers-by with his philosophies on life, religion, politics and current events. On the eastern side of the plaza stands the Terminal Sierra Maestra cruise terminal, which dispatches shiploads of weekly tourists, while nearby the domed Lonja del Comercio is a former commodities market erected in 1909 and restored in 1996 to provide office space for foreign companies with joint ventures in Cuba.

The southern side of the square is taken up by the impressive Iglesia y Monasterio de San Francisco de Asís. Originally constructed in 1608 and rebuilt in the baroque style from 1719 to 1738, San Francisco de Asís was taken over by the Spanish state in 1841 as part of a political move against the powerful religious orders of the day, when it ceased to be a church. Today it’s both a concert hall ( from 5pm or 6pm) hosting classical music and the Museo de Arte Religioso (

from 5pm or 6pm) hosting classical music and the Museo de Arte Religioso ( 862-3467; unguided/guided CUC$2/3;

862-3467; unguided/guided CUC$2/3;  9am-6pm) replete with religious paintings, silverware, woodcarvings and ceramics.

9am-6pm) replete with religious paintings, silverware, woodcarvings and ceramics.

To the side of the Palacio de Gobierno on Churruca is the Coche Mambí (admission free;  9am-2pm Tue-Sat), a 1900 train car built in the US and brought to Cuba in 1912. Put into service as the Presidential Car, it’s a palace on wheels, with a formal dining room, louvered wooden windows and, back in its heyday, fans cooling the car with dry ice.

9am-2pm Tue-Sat), a 1900 train car built in the US and brought to Cuba in 1912. Put into service as the Presidential Car, it’s a palace on wheels, with a formal dining room, louvered wooden windows and, back in its heyday, fans cooling the car with dry ice.

MUSEO DEL RON

You don’t have to be an Añejo Reserva quaffer to enjoy the Museo del Ron ( 861-8051; San Pedro No 262; admission incl guide CUC$5;

861-8051; San Pedro No 262; admission incl guide CUC$5;  9am-5pm Mon-Fri, 10am-4pm Sat & Sun) in the Fundación Havana Club, but it probably helps. The museum, with its bilingual guided tour showing rum-making antiquities and the complex brewing process, gets mixed reviews from travelers, though most give a hearty thumbs-up to the popular dancing lessons held here weekday mornings (Click here).

9am-5pm Mon-Fri, 10am-4pm Sat & Sun) in the Fundación Havana Club, but it probably helps. The museum, with its bilingual guided tour showing rum-making antiquities and the complex brewing process, gets mixed reviews from travelers, though most give a hearty thumbs-up to the popular dancing lessons held here weekday mornings (Click here).

PLAZA VIEJA

Laid out in 1559, Plaza Vieja (Old Square) is Havana’s most architecturally eclectic square where Cuban baroque nestles seamlessly next to Gaudí-inspired art nouveau. Originally called Plaza Nueva (New Square), it was initially used for military exercises and later served as an open-air marketplace. During the Batista regime an ugly underground parking lot was constructed here, but the monstrosity was demolished in 1996 to make way for a massive renovation project. Sprinkled liberally with bars, restaurants and cafes, Plaza Vieja today boasts its own micro-brewery, the Angela Landa primary school and a beautiful fenced-in fountain.

On the northwestern corner is Havana’s cámara oscura (admission CUC$2;  9am-5pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) providing live, 360-degree views of the city from atop a 35m-tall tower. Explanations are in Spanish and English. In the arcade adjacent is the Fototeca de Cuba (

9am-5pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) providing live, 360-degree views of the city from atop a 35m-tall tower. Explanations are in Spanish and English. In the arcade adjacent is the Fototeca de Cuba ( 862-2530; Mercaderes No 307; admission free;

862-2530; Mercaderes No 307; admission free;  10am-5pm Tue-Fri, 9am-noon Sat), a photo gallery with intriguing exhibits by local and international artists.

10am-5pm Tue-Fri, 9am-noon Sat), a photo gallery with intriguing exhibits by local and international artists.

Encased in the plaza’s oldest building is the quirky Museo de Naipes (Muralla No 101; admission free;  9am-6pm Tue-Sun), a playing-card museum with a 2000-strong collection that includes rock stars, rum drinks and round cards. Next door is La Casona Centro de Arte (

9am-6pm Tue-Sun), a playing-card museum with a 2000-strong collection that includes rock stars, rum drinks and round cards. Next door is La Casona Centro de Arte ( 861-8544; Muralla No 107; admission free;

861-8544; Muralla No 107; admission free;  10am-5pm Mon-Fri, 10am-2pm Sat), with great solo and group shows by up-and-coming Cuban artists.

10am-5pm Mon-Fri, 10am-2pm Sat), with great solo and group shows by up-and-coming Cuban artists.

Down the street, the Centro Cultural Pablo de la Torriente Brau ( 861-6251; www.centropablo.cult.cu; Muralla No 63; admission free;

861-6251; www.centropablo.cult.cu; Muralla No 63; admission free;  9am-5:30pm Tue-Sat), a leading cultural institution that was formed under the auspices of the Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (Uneac; Union of Cuban Writers and Artists) in 1996. The center hosts expositions, poetry readings and live acoustic music. Its Salón de Arte Digital is renowned for its groundbreaking digital art.

9am-5:30pm Tue-Sat), a leading cultural institution that was formed under the auspices of the Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (Uneac; Union of Cuban Writers and Artists) in 1996. The center hosts expositions, poetry readings and live acoustic music. Its Salón de Arte Digital is renowned for its groundbreaking digital art.

The square’s most distinctive building is the Gaudí-esque Palacio Cueto (cnr Muralla & Mercaderes), Havana’s finest example of art nouveau that was constructed in 1906. Its outrageously ornate facade once housed a warehouse and a hat factory before it was rented by José Cueto in the 1920s as the Palacio Vienna hotel. Habaguanex has recently pledged to restore the building, empty and unused since the early ’90s.

CALLE OBISPO & AROUND

Narrow, car-free Calle Obispo (literally: Bishop’s Street), Habana Vieja’s main interconnecting artery, is packed with art galleries, shops, music bars and people.

The Museo de Numismático ( 861-5811; Obispo btwn Aguiar & Habana; admission CUC$1;

861-5811; Obispo btwn Aguiar & Habana; admission CUC$1;  9am-4:45pm) brings together various collections of medals, coins and banknotes from around the world, including a stash of 1000 mainly American gold coins (1869–1928) and a full chronology of Cuban banknotes from the 19th century to the present. Opposite, the new Museo 28 Septiembre de los CDR (Obispo btwn Aguiar & Habana; admission CUC$2;

9am-4:45pm) brings together various collections of medals, coins and banknotes from around the world, including a stash of 1000 mainly American gold coins (1869–1928) and a full chronology of Cuban banknotes from the 19th century to the present. Opposite, the new Museo 28 Septiembre de los CDR (Obispo btwn Aguiar & Habana; admission CUC$2;  9am-5pm) dedicates two floors to the nationwide Comites de la Defensa de la Revolución (CDR; Committees for the Defense of the Revolution). Commendable neighborhood-watch schemes, or grassroots spying agencies? You decide. Two blocks further down the Museo de Pintura Mural (Obispo btwn Mercaderes & Oficios; admission free;

9am-5pm) dedicates two floors to the nationwide Comites de la Defensa de la Revolución (CDR; Committees for the Defense of the Revolution). Commendable neighborhood-watch schemes, or grassroots spying agencies? You decide. Two blocks further down the Museo de Pintura Mural (Obispo btwn Mercaderes & Oficios; admission free;  10am-6pm) exhibits some beautifully restored original frescoes in the Casa del Mayorazgo de Recio, popularly considered to be Havana’s oldest surviving house. Two doors down is the Museo de la Orfebrería (

10am-6pm) exhibits some beautifully restored original frescoes in the Casa del Mayorazgo de Recio, popularly considered to be Havana’s oldest surviving house. Two doors down is the Museo de la Orfebrería ( 863-9861; Obispo No 113; admission donation;

863-9861; Obispo No 113; admission donation; 9am-4:30pm Tue-Sat, 9:30am-12:30pm Mon), a silverware museum set out in the house of erstwhile silversmith Gregorio Tabares, who had a workshop here from 1707.

9am-4:30pm Tue-Sat, 9:30am-12:30pm Mon), a silverware museum set out in the house of erstwhile silversmith Gregorio Tabares, who had a workshop here from 1707.

Across Obispo from the Hotel Ambos Mundos lies the Edificio Santo Domingo (Mercaderes btwn Obispo & O’Reilly) on the site of Havana’s old university between 1728 and 1902. It was originally part of a convent; the current incongruous office block dates from the 1950s when the roof was used as a helicopter landing pad. In 2006 Habaguanex rebuilt the convent’s original bell tower and inserted an elaborate baroque doorway onto the building’s eastern side. The result provides an interesting juxtaposition of old and new.

PLAZA DEL CRISTO & AROUND

Habana Vieja’s fifth (and most overlooked) square lies at the west end of the neighborhood, a little apart from the historical core, and has yet to benefit from the City Historian’s makeover. It’s worth a look for the Parroquial del Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje, a church dating from 1732, although there has been a Franciscan hermitage on this site since 1640. Still only partially renovated, the building is most notable for its intricate stained-glass windows and brightly painted wooden ceiling. The Plaza del Cristo also boasts a primary school (hence the noise) and a microcosmic slice of everyday Cuban life sin tourists.

Sidetrack a few blocks up Brasil and you’ll stumble upon the Museo de la Farmacia Habanera (cnr Brasil & Compostela; admission free;  9am-5pm), founded in 1886 by Catalan José Sarrá and once considered the second most important pharmacy in the world. The antique shop still acts as a pharmacy for Cubans, but also as a museum displaying an elegant mock-up of an old drugstore with some interesting historical explanations.

9am-5pm), founded in 1886 by Catalan José Sarrá and once considered the second most important pharmacy in the world. The antique shop still acts as a pharmacy for Cubans, but also as a museum displaying an elegant mock-up of an old drugstore with some interesting historical explanations.

CHURCHES

South of Plaza Vieja is a string of important but little-visited churches. The 1638–43 Iglesia y Convento de Santa Clara ( 866-9327; Cuba No 610; admission CUC$2;

866-9327; Cuba No 610; admission CUC$2;  9am-4pm Mon-Fri) stopped being a convent in 1920. Later this complex was the Ministry of Public Works, and today the Habana Vieja restoration team is based here. You can visit the large cloister and nuns’ cemetery or even spend the night (with reservations far in advance; Click here). The Old Town’s other main convent is the Iglesia y Convento de Nuestra Señora de Belén (

9am-4pm Mon-Fri) stopped being a convent in 1920. Later this complex was the Ministry of Public Works, and today the Habana Vieja restoration team is based here. You can visit the large cloister and nuns’ cemetery or even spend the night (with reservations far in advance; Click here). The Old Town’s other main convent is the Iglesia y Convento de Nuestra Señora de Belén ( 861-7283; Compostela btwn Luz & Acosta; admission CUC$2;

861-7283; Compostela btwn Luz & Acosta; admission CUC$2;  9am-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun), completed in 1718 and run by nuns from the Order of Bethlehem and (later) the Jesuits. Today it is a convalescent home for senior citizens funded by the City Historian’s office.

9am-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun), completed in 1718 and run by nuns from the Order of Bethlehem and (later) the Jesuits. Today it is a convalescent home for senior citizens funded by the City Historian’s office.

Havana’s oldest surviving church (built in 1640 and rebuilt in 1674) is the Iglesia Parroquial del Espíritu Santo ( 862-3140; Acosta 161;

862-3140; Acosta 161;  8am-noon & 3-6pm), with many burials in the crypt. Built in 1755, the Iglesia y Convento de Nuestra Señora de la Merced (Cuba No 806;

8am-noon & 3-6pm), with many burials in the crypt. Built in 1755, the Iglesia y Convento de Nuestra Señora de la Merced (Cuba No 806;  8am-noon & 3-5:30pm) was reconstructed in the 19th century. Beautiful gilded altars, frescoed vaults and a number of old paintings create a sacrosanct mood; there’s a quiet cloister adjacent.

8am-noon & 3-5:30pm) was reconstructed in the 19th century. Beautiful gilded altars, frescoed vaults and a number of old paintings create a sacrosanct mood; there’s a quiet cloister adjacent.

The Iglesia de San Francisco de Paula ( 41-50-37; cnr Leonor Pérez & Desamparados) is one of Havana’s most attractive churches. Fully restored in 2000, it is all that remains of the San Francisco de Paula women’s hospital from the mid-1700s. Lit up at night for concerts, the stained glass, heavy cupola and baroque facade are romantic and inviting.

41-50-37; cnr Leonor Pérez & Desamparados) is one of Havana’s most attractive churches. Fully restored in 2000, it is all that remains of the San Francisco de Paula women’s hospital from the mid-1700s. Lit up at night for concerts, the stained glass, heavy cupola and baroque facade are romantic and inviting.

One of Havana’s newest buildings is the beautiful gold-domed Catedral Ortodoxa Nuestra Señora de Kazán (Av Carlos Manuel de Céspedes btwn Sol & Santa Clara), a Russian Orthodox church built in the early 2000s and consecrated at a ceremony attended by Raúl Castro in October 2008. The church was part of an attempt to reignite Russian-Cuban relations after they went sour in 1991.

MUSEO–CASA NATAL DE JOSé MARTí

The Museo–Casa Natal de José Martí ( 861-3778; Leonor Pérez No 314; admission CUC$1, camera CUC$2;

861-3778; Leonor Pérez No 314; admission CUC$1, camera CUC$2;  9am-5pm Tue-Sat) is a humble, two-story dwelling on the edge of Habana Vieja where the apostle of Cuban independence was born on January 28, 1853. Today it’s a small museum that displays letters, manuscripts, photos, books and other mementos of his life. While not as comprehensive as the Martí museum on Plaza de la Revolución, it’s a charming little abode and well worth a small detour.

9am-5pm Tue-Sat) is a humble, two-story dwelling on the edge of Habana Vieja where the apostle of Cuban independence was born on January 28, 1853. Today it’s a small museum that displays letters, manuscripts, photos, books and other mementos of his life. While not as comprehensive as the Martí museum on Plaza de la Revolución, it’s a charming little abode and well worth a small detour.

Nearby, to the west across Av de Bélgica, is the longest remaining stretch of the old city wall (see boxed text,).

EDIFICIO BACARDí

Finished in 1929, the magnificent Edificio Bacardí (Bacardí building; Av de las Misiones btwn Empedrado & San Juan de Dios;  hours vary) is a triumph of art-deco architecture with a whole host of lavish finishings that somehow manage to make kitschy look cool. Hemmed in by other buildings, it’s hard to get a full kaleidoscopic view of the structure from street level, though the opulent bell tower can be glimpsed from all over Havana. There’s a bar in the lobby and for a few Convertibles you can travel up to the tower for an eagle’s-eye view.

hours vary) is a triumph of art-deco architecture with a whole host of lavish finishings that somehow manage to make kitschy look cool. Hemmed in by other buildings, it’s hard to get a full kaleidoscopic view of the structure from street level, though the opulent bell tower can be glimpsed from all over Havana. There’s a bar in the lobby and for a few Convertibles you can travel up to the tower for an eagle’s-eye view.

IGLESIA DEL SANTO ANGEL CUSTODIO

Originally constructed in 1695, this church ( 861-0469; Compostela No 2;

861-0469; Compostela No 2;  during Mass 7:15am Tue, Wed & Fri, 6pm Thu, Sat & Sun) was pounded by a ferocious hurricane in 1846 after which it was entirely rebuilt in neo-Gothic style. Among the notable historical and literary figures that have passed through its handsome doors are 19th-century Cuban novelist Cirilo Villaverde, who set the main scene of his novel Cecilia Valdés here, as well as Félix Varela and José Martí, who were both baptized in the church in 1788 and 1853 respectively.

during Mass 7:15am Tue, Wed & Fri, 6pm Thu, Sat & Sun) was pounded by a ferocious hurricane in 1846 after which it was entirely rebuilt in neo-Gothic style. Among the notable historical and literary figures that have passed through its handsome doors are 19th-century Cuban novelist Cirilo Villaverde, who set the main scene of his novel Cecilia Valdés here, as well as Félix Varela and José Martí, who were both baptized in the church in 1788 and 1853 respectively.

Centro Habana

CAPITOLIO NACIONAL

The incomparable Capitolio Nacional ( 863-7861; unguided/guided CUC$3/4;

863-7861; unguided/guided CUC$3/4;  9am-8pm) is Havana’s most ambitious and grandiose building, constructed after the ‘Dance of the Millions’ had gifted the Cuban government a seemingly bottomless treasure box of sugar money. Similar to the US Capitol Building in Washington, DC, but (marginally) taller and much richer in detail, the work was initiated by Cuba’s US-backed dictator Gerardo Machado in 1926 and took 5000 workers three years, two months and 20 days to build at a cost of US$17 million. Formerly it was the seat of the Cuban Congress but, since 1959, it has housed the Cuban Academy of Sciences and the National Library of Science and Technology.

9am-8pm) is Havana’s most ambitious and grandiose building, constructed after the ‘Dance of the Millions’ had gifted the Cuban government a seemingly bottomless treasure box of sugar money. Similar to the US Capitol Building in Washington, DC, but (marginally) taller and much richer in detail, the work was initiated by Cuba’s US-backed dictator Gerardo Machado in 1926 and took 5000 workers three years, two months and 20 days to build at a cost of US$17 million. Formerly it was the seat of the Cuban Congress but, since 1959, it has housed the Cuban Academy of Sciences and the National Library of Science and Technology.

Constructed with white Capellanía limestone and block granite, the entrance is guarded by six rounded Doric columns atop a staircase that leads up from the Prado. A stone cupola rising 62m and topped with a replica of 16th-century Florentine sculptor Giambologna’s bronze statue of Mercury in the Palazzo de Bargello looks out over the Havana skyline. Directly below the dome is a copy of a 24-carat diamond set in the floor. Highway distances between Havana and all sites in Cuba are calculated from this point.

The entryway opens up into the Salón de los Pasos Perdidos (Room of the Lost Steps, so named because of its unusual acoustics), at the center of which is the statue of the republic, an enormous bronze woman standing 11m tall and symbolizing the mythic Guardian of Virtue and Work. In size, it’s smaller only than the gold Buddha in Nava, Japan, and the Lincoln Monument in Washington, DC.

REAL FáBRICA DE TABACOS PARTAGáS

One of Havana’s oldest and most famous cigar factories, the landmark neoclassical Real Fábrica de Tabacos Partagás ( 862-0086; Industria No 520 btwn Barcelona & Dragones; tours CUC$10;

862-0086; Industria No 520 btwn Barcelona & Dragones; tours CUC$10;  every 15 min 9:30-11am & 12:30-3pm) was founded in 1845 by a Spaniard named Jaime Partagás. Today some 400 workers toil for up to 12 hours a day in here rolling such famous cigars as Montecristos and Cohibas. As far as tours go, Partagás is the most popular and reliable factory to visit. Tour groups check out the ground floor first, where the leaves are unbundled and sorted, before proceeding to the upper floors to watch the tobacco get rolled, pressed, adorned with a band and boxed. Though interesting in an educational sense, the tours here are often rushed and a little robotic and some visitors find they smack of a human zoo. Still, if you have even a passing interest in tobacco and/or Cuban work environments, it’s probably worth a peep.

every 15 min 9:30-11am & 12:30-3pm) was founded in 1845 by a Spaniard named Jaime Partagás. Today some 400 workers toil for up to 12 hours a day in here rolling such famous cigars as Montecristos and Cohibas. As far as tours go, Partagás is the most popular and reliable factory to visit. Tour groups check out the ground floor first, where the leaves are unbundled and sorted, before proceeding to the upper floors to watch the tobacco get rolled, pressed, adorned with a band and boxed. Though interesting in an educational sense, the tours here are often rushed and a little robotic and some visitors find they smack of a human zoo. Still, if you have even a passing interest in tobacco and/or Cuban work environments, it’s probably worth a peep.

PARQUE DE LA FRATERNIDAD

Leafy Parque de la Fraternidad was established in 1892 to commemorate the fourth centenary of the Spanish landing in the Americas. A few decades later it was remodeled and renamed to mark the 1927 Pan-American Conference. The name is meant to signify American brotherhood, hence the many busts of Latin and North American leaders that embellish the green areas – including one of US president, Abraham Lincoln. Today the park is the terminus of numerous metro bus routes, and is sometimes referred to as ‘Jurassic Park’ for the plethora of photogenic old American cars now used as colectivos (collective taxis) that congregate here.

The Fuente de la India (on a traffic island opposite the Hotel Saratoga) is a white Carrara marble fountain, carved by Giuseppe Gaginni in 1837 for the Count of Villanueva. It portrays a regal Indian woman adorned with a crown of eagle’s feathers and seated on a throne surrounded by four gargoylesque dolphins. In one hand she holds a horn-shaped basket filled with fruit, in the other a shield bearing the city’s coat of arms.

Just east of the sculpture, across Paseo de Martí is the Asociación Cultural Yoruba de Cuba ( 863-5953; Paseo de Martí No 615; admission CUC$10;

863-5953; Paseo de Martí No 615; admission CUC$10;  9am-4pm Mon-Sat). A museum here provides a worthwhile overview of the Santería religion, the saints and their powers, although some travelers have complained that the exhibits don’t justify the price. There are tambores (Santería drum ceremonies) here on alternate Fridays at 4:30pm. Note that there’s a church dress code for the tambores (no shorts or tank tops).

9am-4pm Mon-Sat). A museum here provides a worthwhile overview of the Santería religion, the saints and their powers, although some travelers have complained that the exhibits don’t justify the price. There are tambores (Santería drum ceremonies) here on alternate Fridays at 4:30pm. Note that there’s a church dress code for the tambores (no shorts or tank tops).

A little out on a limb but well worth the walk is the Iglesia del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (Av Simon Bolivar btwn Gervasio & Padre Varela), an inspiring marble creation with a distinctive white steeple, where you can enjoy a few precious minutes of quiet and cool contemplation away from the craziness of the street. This church is rightly famous for its magnificent stained-glass windows, and the light that penetrates through the eaves first thing in the morning (when the church is deserted) gives the place an almost ethereal quality.

PARQUE CENTRAL & AROUND

Diminutive Parque Central is a scenic haven from the belching buses and roaring taxis that ply their way along the Prado. The park, long a microcosm of daily Havana life, was expanded to its present size in the late 19th century after the city walls were knocked down, and the marble statue of José Martí (1905) at its center was the first of thousands to be erected in Cuba. Raised on the 10th anniversary of the poet’s death, the monument is ringed by 28 palm trees planted to signify Martí’s birth date: January 28. Hard to miss over to one side is the group of baseball fans who linger 24/7 at the famous Esquina Caliente (see boxed text,).

On the park’s southwest corner is the ornate neobaroque Centro Gallego (Paseo de Martí No 458), erected as a Galician social club between 1907 and 1914. The Centro was built around the existing Teatro Tacón, which opened in 1838 with five masked Carnaval dances. This connection is the basis of claims by the present 2000-seat Gran Teatro de La Habana ( 861-3077; guided tours CUC$2;

861-3077; guided tours CUC$2;  9am-6pm) that it’s the oldest operating theater in the Western hemisphere. History notwithstanding, the architecture is brilliant, as are many of the weekend performances (Click here).

9am-6pm) that it’s the oldest operating theater in the Western hemisphere. History notwithstanding, the architecture is brilliant, as are many of the weekend performances (Click here).

Just across the San Rafael pedestrian mall is the Hotel Inglaterra, Havana’s oldest hotel, which first opened its doors in 1856 on the site of a popular bar called El Louvre (the hotel’s alfresco bar still bears the name). Facing leafy Parque Central, the building exhibits neoclassical design features in vogue at the time, although the interior decor is distinctly Moorish. At a banquet here in 1879, José Martí made a speech advocating Cuban independence, and much later US journalists covering the Spanish-Cuban-American War stayed at the hotel.

A detour along Calle San Rafael, a riot of peso stalls, 1950s department store and local cinemas, gives an immediate insight into everyday life in economically challenged Cuba.

MUSEO NACIONAL DE BELLAS ARTES

Cuba has a huge art culture and its dual-site art museum rivals its counterpart in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for the title of ‘best art museum in the Caribbean.’ You can spend a whole day here viewing everything from Greek ceramics to Cuban pop art.

Arranged inside the fabulously eclectic Centro Asturianas (a work of art in its own right), the Colección de Arte Universal ( 863-9484; cnr Agramonte & San Rafael; admission CUC$5, children under 14 free;

863-9484; cnr Agramonte & San Rafael; admission CUC$5, children under 14 free;  10am-6pm Tue-Sat, 10am-2pm Sun) exhibits international art from 500 BC to the present day on three separate floors. Highlights include an extensive Spanish collection (with a canvas by El Greco), some 2000-year-old Roman mosaics, Greek pots from the 5th century BC and a suitably refined Gainsborough canvas (in the British room).

10am-6pm Tue-Sat, 10am-2pm Sun) exhibits international art from 500 BC to the present day on three separate floors. Highlights include an extensive Spanish collection (with a canvas by El Greco), some 2000-year-old Roman mosaics, Greek pots from the 5th century BC and a suitably refined Gainsborough canvas (in the British room).

Two blocks away, the Colección de Arte Cubano ( 861-3858; Trocadero btwn Agramonte & Av de las Misiones; admission CUC$5;

861-3858; Trocadero btwn Agramonte & Av de las Misiones; admission CUC$5;  10am-6pm Tue-Sat, 10am-2pm Sun) displays purely Cuban art and, if you’re pressed for time, is the better of the duo. Works are displayed in chronological order starting on the 3rd floor and are surprisingly varied. Artists to look out for are Guillermo Collazo, considered to be the first truly great Cuban artist, Rafael Blanco with his cartoon-like paintings and sketches, Raúl Martínez, a master of 1960s Cuban pop art, and the Picasso-like Wilfredo Lam.

10am-6pm Tue-Sat, 10am-2pm Sun) displays purely Cuban art and, if you’re pressed for time, is the better of the duo. Works are displayed in chronological order starting on the 3rd floor and are surprisingly varied. Artists to look out for are Guillermo Collazo, considered to be the first truly great Cuban artist, Rafael Blanco with his cartoon-like paintings and sketches, Raúl Martínez, a master of 1960s Cuban pop art, and the Picasso-like Wilfredo Lam.

MUSEO DE LA REVOLUCIóN

The Museo de la Revolución ( 862-4093; Refugio No 1; unguided/guided CUC$4/6, camera extra;

862-4093; Refugio No 1; unguided/guided CUC$4/6, camera extra;  10am-5pm) is housed in the former Presidential Palace, constructed between 1913 and 1920 and used by a string of cash-embezzling Cuban presidents, culminating in Fulgencio Batista. The world-famous Tiffany’s of New York decorated the interior, and the shimmering Salón de los Espejos (Room of Mirrors) was designed to resemble the room of the same name at the Palace of Versailles. In March 1957 the palace was the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt against Batista led by revolutionary student leader José Antonio Echeverría. The museum itself descends chronologically from the top floor starting with Cuba’s pre-Columbian culture and extending to the present-day socialist regime (with mucho propaganda). The downstairs rooms have some interesting exhibits on the 1953 Moncada attack and the life of Che Guevara, and highlight a Cuban penchant for displaying blood-stained military uniforms. Most of the labels are in English and Spanish. In front of the building is a fragment of the former city wall as well as an SAU-100 tank used by Castro during the 1961 battle of the Bay of Pigs.

10am-5pm) is housed in the former Presidential Palace, constructed between 1913 and 1920 and used by a string of cash-embezzling Cuban presidents, culminating in Fulgencio Batista. The world-famous Tiffany’s of New York decorated the interior, and the shimmering Salón de los Espejos (Room of Mirrors) was designed to resemble the room of the same name at the Palace of Versailles. In March 1957 the palace was the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt against Batista led by revolutionary student leader José Antonio Echeverría. The museum itself descends chronologically from the top floor starting with Cuba’s pre-Columbian culture and extending to the present-day socialist regime (with mucho propaganda). The downstairs rooms have some interesting exhibits on the 1953 Moncada attack and the life of Che Guevara, and highlight a Cuban penchant for displaying blood-stained military uniforms. Most of the labels are in English and Spanish. In front of the building is a fragment of the former city wall as well as an SAU-100 tank used by Castro during the 1961 battle of the Bay of Pigs.

In the space behind you’ll find the Pavillón Granma, a memorial to the 18m yacht that carried Fidel Castro and 81 other revolutionaries from Tuxpán, Mexico to Cuba in December 1956. It’s encased in glass and guarded 24 hours a day, presumably to stop anyone from breaking in and making off for Florida in it. The pavilion is surrounded by other vehicles associated with the Revolution and is accessible from the Museo de la Revolución.

PRADO (PASEO DE MARTí)

Construction of this stately European-style boulevard (officially known as Paseo de Martí) – the first street outside the old city walls – began in 1770, and the work was completed in the mid-1830s during the term of Captain General Miguel Tacón (1834–38). The original idea was to create a boulevard as splendid as any found in Paris or Barcelona (Prado owes more than a passing nod to Las Ramblas). The famous bronze lions that guard the central promenade at either end were added in 1928.

Notable Prado buildings include the neo-Renaissance Palacio de los Matrimonios (Paseo de Martí No 302), the streamline-moderne Teatro Fausto (cnr Paseo de Martí & Colón) and the neoclassical Escuela Nacional de Ballet (cnr Paseo de Martí & Trocadero), Alicia Alonso’s famous ballet school.

PARQUE DE LOS ENAMORADOS

Preserved in Parque de los Enamorados (Lovers’ Park), surrounded by streams of speeding traffic, lies a surviving section of the colonial Cárcel or Tacón Prison, built in 1838, where many Cuban patriots including José Martí were imprisoned. A brutal place that sent unfortunate prisoners off to perform hard labor in the nearby San Lázaro quarry, the prison was finally demolished in 1939 with the park that took its place dedicated to the memory of those who had suffered so horribly within its walls. Two tiny cells and an equally minute chapel are all that remain. The beautiful wedding cake–like building (art nouveau with a dash of eclecticism) behind the park, flying the Spanish flag, is the old Palacio Velasco (1912), now the Spanish embassy.

Beyond that is the Memorial a los Estudiantes de Medicina, a fragment of wall encased in marble marking the spot where eight Cuban medical students chosen at random were shot by the Spanish in 1871 as a reprisal for allegedly desecrating the tomb of a Spanish journalist (in fact, they didn’t do it).