Guantánamo Province |

|

GUANTÁNAMO

AROUND GUANTÁNAMO US NAVAL BASE

ZOOLÓGICO DE PIEDRAS

SOUTH COAST

PUNTA DE MAISÍ

BOCA DE YUMURÍ

BARACOA

NORTHWEST OF BARACOA

PARQUE NACIONAL ALEJANDRO DE HUMBOLDT

Say you’re from Guantánamo to anyone outside Cuba, and they’ll probably assume that you’re either a US Navy Seal on annual leave, or an ex-inmate from one of the world’s most notorious jails. But Cuba’s wettest, driest, hottest, oldest and most mountainous province is far more than an anachronistic US naval base. Cuba in the modern sense started here in August 1511, when Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar and his band of 400 colonizers landed uninvited on the rain-lashed eastern coastline. Making camp near a mysterious flat-topped mountain known to the natives as El Yunque, they christened their new settlement Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Baracoa and quickly made enemies with the local Taínos.

Baracoa lives on, of course; no longer the island’s capital, but still one of its most beguiling settlements, cut off for centuries by the shadowy Sierra del Puril – Cuba’s Himalayas – and beautifully unique as a consequence.

To get there you’ll need to take La Farola, the province’s rugged transport artery and one of the seven engineering marvels of modern Cuba, a weaving roller coaster that travels from the dry cacti-littered southern coast up into the humid Cuchillas de Toa mountains. Overlaid by the fecund Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt (a Unesco World Heritage Site), this heavily protected zone is considered to be one of the last few swathes of virgin rainforest left in the Caribbean and guards an incredible array of endemic species.

Closer to sea level, Cuba’s eastern extremity is scattered with myriad archaeological sites that exhibit important vestiges of the island’s pre-Columbian cultural jigsaw. Separated from the country’s cosmopolitan urban centers, the native bloodlines are purer here and, around the isolated Boca de Yumurí, you’ll find people who still claim indigenous Indian ancestry.

History

Long before the arrival of the Spanish, Taíno Indians populated the mountains and forests around Guantánamo forging a living as fishermen, hunters and small-scale farmers. Columbus first arrived in the region in November 1492, a month or so after his initial landfall near Gibara, and planted a small wooden cross in a beautiful bay he ceremoniously christened Porto Santo – after an idyllic island off Portugal where he had enjoyed his honeymoon. The Spanish returned again in 1511 under the auspices of Columbus’ son Diego in a flotilla of four ships and 400 men that included the island’s first governor Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar. Building a makeshift fort constructed from wood, the conquistadors consecrated the island’s first colonial settlement, Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Baracoa, and watched helplessly as the town was subjected to repeated attacks from hostile local Indians led by a rebellious cacique (chief) known as Hatuey.

Declining in importance after the capital moved to Santiago in 1515, the Guantánamo region became Cuba’s Siberia – a mountainous and barely penetrable rural backwater where prisoners were exiled and old traditions survived. In the late 18th century the area was recolonized by French immigrants from Haiti who tamed the difficult terrain in order to cultivate coffee, cotton and sugarcane on the backs of African slaves. Following the Spanish-Cuban-American War, a brand new foe took up residence in Guantánamo Bay – the all-powerful Americans – intent on protecting their economic interests in the strategically important Panama Canal region. Despite repeated bouts of mudslinging in the years since, the not-so-welcome Yanquis, as they are popularly known, have repeatedly refused to budge.

Parks & Reserves

A large swathe of northern Guantánamo province is given over to the Cuchillas de Toa, designated a Unesco Biosphere Reserve in 1987. Approximately one-third of this area is afforded extra protection in the Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt, which in 2001 was named a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Getting There & Around

The Víazul bus service passes through Guantánamo all the way to Baracoa twice daily. Guantánamo is also accessible by train from Havana but the line doesn’t extend as far as Baracoa. Daily trucks link Baracoa with Moa in Holguín province via a rutted road. Both Guantánamo and Baracoa have airports with two to five flights a week to Havana.

Return to beginning of chapter

GUANTÁNAMO

pop 244,603

Despite the notoriety gained in the ongoing schoolyard-style feud between Cuba and the US, there’s nothing visually remarkable about Guantánamo – which accounts, in part, for its low profile on the tourist ‘circuit.’ But, amid the ugly grey buildings and hopelessly decaying infrastructure a buoyant culture has been putting up a brave rearguard action. Between them, the feisty Guantanameros have produced 11 gold medals, blasted a man into orbit (Cuban cosmonaut, Arnaldo Méndez) and spawned their own unique brand of traditional son music known as son-changüí. Then there’s the small matter of that song (see boxed text,).

‘Discovered’ by Columbus in 1494 and given the once-over by the ever curious British 250 years later, a settlement wasn’t built here until 1819, when French plantation owners evicted from Haiti founded the town of Santa Catalina del Saltadero del Guaso between the Jaibo, Bano and Guaso Rivers. In 1843 the burgeoning city changed its name to Guantánamo and in 1903 the bullish US Navy took up residence in the bay next door. The sparks have been flying ever since.

Orientation

Mariana Grajales Airport (airport code GAO) is 16km southeast of Guantánamo, 4km off the road to Baracoa. Parque Martí, Guantánamo’s central square, is several blocks south of the train station and 5km east of the Terminal de Ómnibus (bus station). Villa La Lupe, the main tourist hotel, is 5km northwest of the town.

Information

BOOKSTORES

- Universal (Pedro A Pérez No 907;

9am-noon & 2-5pm Mon-Fri, 9am-noon Sat)

9am-noon & 2-5pm Mon-Fri, 9am-noon Sat)

INTERNET ACCESS & TELEPHONE

- Etecsa Telepunto (cnr Aguilera & Los Maceos; per hr CUC$6;

8:30am-7:30pm) Four computers.

8:30am-7:30pm) Four computers.

LIBRARIES

- Biblioteca Policarpo Pineda Rustán (cnr Los Maceos & Emilio Giro;

8am-9pm Mon-Fri, 8am-5pm Sat, 9am-noon Sun) An architectural landmark.

8am-9pm Mon-Fri, 8am-5pm Sat, 9am-noon Sun) An architectural landmark.

MEDIA

- Radio Trinchera Antimperialista CMKS Trumpets the word over 1070AM.

- Venceremos & Lomería Two local newspapers published on Saturday.

MEDICAL SERVICES

- Farmacia Principal Municipal (cnr Calixto García & Aguilera;

24hr) On the northeast corner of Parque Martí.

24hr) On the northeast corner of Parque Martí. - Hospital Agostinho Neto (

35-54-50; Carretera de El Salvador Km 1;

35-54-50; Carretera de El Salvador Km 1;  24hr) At the west end of Plaza Mariana Grajales near Hotel Guantánamo. It will help foreigners in an emergency.

24hr) At the west end of Plaza Mariana Grajales near Hotel Guantánamo. It will help foreigners in an emergency.

MONEY

- Banco de Crédito y Comercio (Calixto García btwn Emilio Giro & Bartolomé Masó)

- Cadeca (

32-65-33; cnr Calixto García & Prado;

32-65-33; cnr Calixto García & Prado;  8:30am-6pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun)

8:30am-6pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun)

POST

- Post office (Pedro A Pérez;

8am-1pm & 2-6pm Mon-Sat) On the west side of Parque Martí. There’s also a DHL office here.

8am-1pm & 2-6pm Mon-Sat) On the west side of Parque Martí. There’s also a DHL office here.

TRAVEL AGENCIES

- Havanatur (

32-63-65; Aguilera btwn Calixto García & Los Maceos;

32-63-65; Aguilera btwn Calixto García & Los Maceos;  9am-noon & 1-4pm Mon-Fri)

9am-noon & 1-4pm Mon-Fri)

Dangers & Annoyances

Guantánamo is a big city with a mellow town feel that pickpockets sometimes exploit. Stay alert especially on public transport and during Noches Guantanameras.

Sights

Ostensibly unexciting, Guantánamo’s geometric city grid has a certain rhythm. The tree-lined Av Camilo Cienfuegos with its morning exercisers, bizarre sculptures and central Ramblas-style walkway is the best place to get into the groove.

Though it’s no Louvre, the esoteric Museo Municipal (cnr José Martí & Prado; admission CUC$1;  2-6pm Mon, 8am-noon & 3-7pm Tue-Sat) contains some interesting US Naval Base ephemera including prerevolutionary day passes and some revealing photos.

2-6pm Mon, 8am-noon & 3-7pm Tue-Sat) contains some interesting US Naval Base ephemera including prerevolutionary day passes and some revealing photos.

The unspectacular but noble Parroquia de Santa Catalina de Riccis, in Parque Martí, dates from 1863. In front of the church is a statue of local hero, Mayor General Pedro A Pérez, erected in 1928, opposite a tulip fountain and diminutive glorieta (bandstand).

Local architect Leticio Salcines (1888–1973) left a number of impressive works around Guantánamo, including the turreted market building Plaza del Mercado Agro Industrial (cnr Los Maceos & Prado), the train station, and his personal residence, the 1916 Palacio Salcines (cnr Pedro A Pérez & Prado; admission CUC$1;  8am-noon & 2-6pm Mon-Fri), a triumph of eclecticism and a monument said to be the building most representative of Guantánamo. The Palacio is now a small museum exhibiting colorful frescoes, Japanese porcelain and a rusty old music box that pipes out rather disappointing Mozart. A guided tour (CUC$1) makes the dull exhibits infinitely more interesting. On the palace’s turret is La Fama, a sculpture designed by Italian artist Americo Chine that serves as the symbol of Guantánamo, her trumpet announcing good and evil. Salcines also designed the beautiful provincial library Biblioteca Policarpo Pineda Rustán (cnr Los Maceos & Emilio Giro), which was once the city hall (1934–51). Trials of Fulgencio Batista’s thugs were held here in 1959, and a number were killed when they snatched a rifle and tried to escape.

8am-noon & 2-6pm Mon-Fri), a triumph of eclecticism and a monument said to be the building most representative of Guantánamo. The Palacio is now a small museum exhibiting colorful frescoes, Japanese porcelain and a rusty old music box that pipes out rather disappointing Mozart. A guided tour (CUC$1) makes the dull exhibits infinitely more interesting. On the palace’s turret is La Fama, a sculpture designed by Italian artist Americo Chine that serves as the symbol of Guantánamo, her trumpet announcing good and evil. Salcines also designed the beautiful provincial library Biblioteca Policarpo Pineda Rustán (cnr Los Maceos & Emilio Giro), which was once the city hall (1934–51). Trials of Fulgencio Batista’s thugs were held here in 1959, and a number were killed when they snatched a rifle and tried to escape.

For a fuller exposé of Guantánamo’s interesting architectural heritage you might want to stop by at the Oficina de Monumentos y Sitios Históricos (Los Maceos btwn Emilio Giro & Flor Crombet). Ask about a map of city walking trails.

The huge bombastic Monument to the Heroes, glorifying the Brigada Fronteriza ‘that defends the forward trench of socialism on this continent,’ dominates Plaza Mariana Grajales (opposite the Hotel Guantánamo),

one of the more impressive ‘Revolution squares’ on the island.

Sleeping

CASAS PARTICULARES

Lissett Foster Lara ( 32-59-70; Pedro A Pérez No 761 btwn Prado & Jesús del Sol; r CUC$20-25;

32-59-70; Pedro A Pérez No 761 btwn Prado & Jesús del Sol; r CUC$20-25;  ) Like many Guantanameras, Lissett speaks perfect English and her house is polished, comfortable and decked out with the kind of plush fittings that wouldn’t be out of place in a North American suburb. The highlight here, in more ways than one, is the roof terrace where you can recline above the car honks and street hassle for an hour or three.

) Like many Guantanameras, Lissett speaks perfect English and her house is polished, comfortable and decked out with the kind of plush fittings that wouldn’t be out of place in a North American suburb. The highlight here, in more ways than one, is the roof terrace where you can recline above the car honks and street hassle for an hour or three.

Osmaida Blanco Castillo ( 32-51-93; Pedro A Pérez No 664 btwn Paseo & Narciso López; r CUC$20-25;

32-51-93; Pedro A Pérez No 664 btwn Paseo & Narciso López; r CUC$20-25;  ) Another well-appointed place with a superb roof terrace (with bar!), two spacious rooms, a shady patio (with fish tank) and excellent meals available (you’ll need them in this town). If it’s full, try house 670A in the same street.

) Another well-appointed place with a superb roof terrace (with bar!), two spacious rooms, a shady patio (with fish tank) and excellent meals available (you’ll need them in this town). If it’s full, try house 670A in the same street.

HOTELS

Hotel Guantánamo (Islazul;  38-10-15; Calle 13 Norte btwn Ahogados & 2 de Octubre; s/d CUC$23/30;

38-10-15; Calle 13 Norte btwn Ahogados & 2 de Octubre; s/d CUC$23/30;

) A lick of paint, a quick cleanup around the lobby and some newly planted flowers in the garden, and hey presto – the Hotel Guantánamo’s back in business after a couple of years serving as a convalescent home for Operación Milagros. It’s still a long way from the Ritz, but at least the generic rooms are clean, the pool has water in it, and there’s a good reception bar-cafe mixing up tempting mojitos and serving coffee.

) A lick of paint, a quick cleanup around the lobby and some newly planted flowers in the garden, and hey presto – the Hotel Guantánamo’s back in business after a couple of years serving as a convalescent home for Operación Milagros. It’s still a long way from the Ritz, but at least the generic rooms are clean, the pool has water in it, and there’s a good reception bar-cafe mixing up tempting mojitos and serving coffee.

Villa La Lupe (Islazul;  38-26-12; Carretera de El Salvador Km 3.5; s/d CUC$23/30;

38-26-12; Carretera de El Salvador Km 3.5; s/d CUC$23/30;

) Located 5km north of the city on the road to El Salvador, Villa La Lupe – named after a song by Moncada and Granma survivor, Juan Almeida – is Guantánamo’s best lodging option, despite its out-of-town location. Attractive, spacious cabins are arranged around a clean central swimming pool and the adjacent restaurant, which serves the usual staples of pork and rice, overlooks a leafy river where young girls celebrate their quinciñeras (15th birthdays). For music geeks the words of Almeida’s famous song are emblazoned onto a granite wall.

) Located 5km north of the city on the road to El Salvador, Villa La Lupe – named after a song by Moncada and Granma survivor, Juan Almeida – is Guantánamo’s best lodging option, despite its out-of-town location. Attractive, spacious cabins are arranged around a clean central swimming pool and the adjacent restaurant, which serves the usual staples of pork and rice, overlooks a leafy river where young girls celebrate their quinciñeras (15th birthdays). For music geeks the words of Almeida’s famous song are emblazoned onto a granite wall.

Eating

RESTAURANTS

Restaurante Vegetariano Guantánamo (Pedro A Pérez;  noon-2:30pm & 5-10:30pm;

noon-2:30pm & 5-10:30pm;  ) Vegetarians needn’t get too excited; this is a slightly scruffy-looking local peso place situated by the main park, though it could help you jump off the daily cheese-sandwich and tortilla treadmill.

) Vegetarians needn’t get too excited; this is a slightly scruffy-looking local peso place situated by the main park, though it could help you jump off the daily cheese-sandwich and tortilla treadmill.

Cafetería Oroazul (cnr Los Maceos & Aguilera) A good place to catch a breather, feel the cool ceiling fan on your face and grab a revitalizing plate of spaghetti cooked a good 10 minutes past al dente. There are cleanish toilets inside.

El Rápido (cnr Flor Crombet & Los Maceos;  10am-10pm) It’s a testament to Guantánamo’s dire dining scene that you may have to resort to Cuba’s gastronomically challenged fast-food chain. Rapid it ain’t.

10am-10pm) It’s a testament to Guantánamo’s dire dining scene that you may have to resort to Cuba’s gastronomically challenged fast-food chain. Rapid it ain’t.

Restaurante Ensueños (Calle 15 Norte;

Restaurante Ensueños (Calle 15 Norte;  noon-midnight) There’s no sign; just a nude statue denoting the entrance to what is, by process of elimination, Guantánamo’s best restaurant. Housed in a diminutive modern house tucked away behind the Hotel Guantánamo, the Palmares-run Ensueños serves up chicken, lobster and fish in some interesting sauces. Your agua con gas (mineral water) will probably go flat waiting for the meal to emerge from the kitchen, but who cares; for once it’s worth the wait.

noon-midnight) There’s no sign; just a nude statue denoting the entrance to what is, by process of elimination, Guantánamo’s best restaurant. Housed in a diminutive modern house tucked away behind the Hotel Guantánamo, the Palmares-run Ensueños serves up chicken, lobster and fish in some interesting sauces. Your agua con gas (mineral water) will probably go flat waiting for the meal to emerge from the kitchen, but who cares; for once it’s worth the wait.

GROCERIES

Plaza del Mercado Agro Industrial (cnr Los Maceos & Prado;  7am-7pm Mon-Sat, 7am-2pm Sun) The town’s public vegetable market is a red-domed Leticio Salcines creation and rather striking – both inside and out.

7am-7pm Mon-Sat, 7am-2pm Sun) The town’s public vegetable market is a red-domed Leticio Salcines creation and rather striking – both inside and out.

Agropecuario (Calle 13) The city’s other outdoor market is opposite Plaza Mariana Grajales, just west of the Hotel Guantánamo; it sells bananas, yucca and onions by the truckload, plus plenty of peso snacks.

Panadería La Palmita (Flor Crombet No 305 btwn Calixto García & Los Maceos;  7:30am-5pm Mon-Sat) sells fresh bread, while the Coppelia (cnr Pedro A Pérez & Bernabe Varona) dishes out ice cream.

7:30am-5pm Mon-Sat) sells fresh bread, while the Coppelia (cnr Pedro A Pérez & Bernabe Varona) dishes out ice cream.

Drinking

La Ruina (cnr Calixto García & Emilio Giro;  10am-1am) This shell of a ruined colonial building has 9m ceilings and a crusty feet-on-the-table kind of ambience. There are plenty of benches to prop you up after you’ve downed yet another bottle of beer and a popular karaoke scene for those with reality-TV ambitions. The bar menu’s good for a snack lunch.

10am-1am) This shell of a ruined colonial building has 9m ceilings and a crusty feet-on-the-table kind of ambience. There are plenty of benches to prop you up after you’ve downed yet another bottle of beer and a popular karaoke scene for those with reality-TV ambitions. The bar menu’s good for a snack lunch.

Entertainment

Guantánamo has its own distinctive musical culture, a subgenre of son known as son-changüí that mixes traditional riffs with Spanish, Afro-Cuban and even French influences. Its main exponent was Guantánamo-born Elio Revé (1930–97), former leader of the Orquesta Revé. You can get a taste at the following venues.

Casa de la Trova (Máximo Gómez No 1062; admission CUC$1;  8pm-1am) Guantánamo has two of these casas, although only this one was functioning at the time of writing. A bright royal-blue building on a quiet urban street, it offers the usual blend of traditional sounds with a son-changüí bias. Closed Monday.

8pm-1am) Guantánamo has two of these casas, although only this one was functioning at the time of writing. A bright royal-blue building on a quiet urban street, it offers the usual blend of traditional sounds with a son-changüí bias. Closed Monday.

Casa de la Música (Calixto García btwn Flor Crombet & Emilio Giro) Another well-maintained, more concert-orientated venue, with Thursday rap peñas (performances) and Sunday trova (traditional music) matinees.

Tumba Francesa Pompadour (Serafín Sánchez No 715) This peculiarly Guantánamo nightspot situated four blocks east of the train station specializes in a unique form of Haitian-style dancing. Programs (generally listed on the door) include mi tumba baile (tumba dance), encuentro tradicional (traditional get-together) and peña campesina (country music).

Tumba Francesa Pompadour (Serafín Sánchez No 715) This peculiarly Guantánamo nightspot situated four blocks east of the train station specializes in a unique form of Haitian-style dancing. Programs (generally listed on the door) include mi tumba baile (tumba dance), encuentro tradicional (traditional get-together) and peña campesina (country music).

Casa de la Cultura ( 32-63-91; Pedro A Pérez; admission free) In the former Casino Español, on the west side of Parque Martí, this venue holds classical concerts and Afro-Cuban dance performances.

32-63-91; Pedro A Pérez; admission free) In the former Casino Español, on the west side of Parque Martí, this venue holds classical concerts and Afro-Cuban dance performances.

Club Nevada ( 35-54-47; Pedro A Pérez No 1008 Altos cnr Bartolomé Masó; admission CUC$1) For the city’s funkiest disco, head to this tiled-terrace rooftop, which blasts out salsa mixed with disco standards.

35-54-47; Pedro A Pérez No 1008 Altos cnr Bartolomé Masó; admission CUC$1) For the city’s funkiest disco, head to this tiled-terrace rooftop, which blasts out salsa mixed with disco standards.

Cine America (Calixto García) A block north of Parque Martí, this is the city’s best movie house. Check the taped-up posters outside.

Saturday nights are reserved for Noches Guantanameras, when Calle Pedro A Pérez is closed to traffic and stalls are set up in the street. Locals enjoy whole roast pig, belting music and copious amounts of rum. Watch out for the borrachos (drunks)!

Baseball games are played from October to April at the Estadio Van Troi in Reparto San Justo, 1.5km south of the Servi-Cupet gas station. Despite a strong sporting tradition, Guantánamo – nicknamed Los Indios – are perennial underachievers who haven’t made the play-offs since 1999.

Shopping

No one comes to Guantánamo to shop but, if you want a local souvenir that doesn’t have a US flag emblazoned on it, try the Fondo de Bienes Culturales (1st fl, Calixto García No 855) on the east side of Parque Martí.

Photo Service (Los Maceos btwn Aguilera & Flor Crombet) sells film, prints and batteries.

Getting There & Away

AIR

Cubana ( 35-45-33; Calixto García No 817) flies five times a week (CUC$124 one-way, 2½ hours) from Havana to Mariana Grajales Airport (

35-45-33; Calixto García No 817) flies five times a week (CUC$124 one-way, 2½ hours) from Havana to Mariana Grajales Airport ( 35-54-54). There are no international flights to this airport.

35-54-54). There are no international flights to this airport.

BUS & TRUCK

The rather inconveniently placed Terminal de Ómnibus (bus station) is 5km west of the center on the old road to Santiago (a continuation of Av Camilo Cienfuegos). A taxi from the Hotel Guantánamo should cost CUC$3.

There are daily Víazul (www.viazul.com) buses daily to Baracoa (CUC$10, 9:30am) and Santiago de Cuba (CUC$6, 5:25pm).

Trucks to Santiago de Cuba and Baracoa also leave from the Terminal de Ómnibus. These will allow you to disembark in the smaller towns in between.

Trucks for Moa park on the road to El Salvador north of town near the entrance to the Autopista.

CAR

The Autopista Nacional to Santiago de Cuba ends near Embalse La Yaya, 25km west of Guantánamo, where the road joins the Carretera Central (at the time of writing work had begun to extend this road). At El Cristo, 12km outside Santiago de Cuba, you rejoin the Autopista. To drive to Guantánamo from Santiago de Cuba, follow the Autopista Nacional north about 12km to the top of the grade, then take the first turn to the right. Signposts are sporadic and vague, so take a good map and keep alert.

TRAIN

The train station ( 32-55-18; Pedro A Pérez), several blocks north of Parque Martí, has one departure for Havana (CUC$32, 9:05pm) on alternate days. This train also stops at Camagüey (CUC$13), Ciego de Ávila (CUC$16), Guayos (CUC$20; you should disembark here for Sancti Spíritus), Santa Clara (CUC$22) and Matanzas (CUC$29). There was no service to Santiago de Cuba at the time of writing. Purchase tickets in the morning of the day the train departs at the office on Pedro A Pérez.

32-55-18; Pedro A Pérez), several blocks north of Parque Martí, has one departure for Havana (CUC$32, 9:05pm) on alternate days. This train also stops at Camagüey (CUC$13), Ciego de Ávila (CUC$16), Guayos (CUC$20; you should disembark here for Sancti Spíritus), Santa Clara (CUC$22) and Matanzas (CUC$29). There was no service to Santiago de Cuba at the time of writing. Purchase tickets in the morning of the day the train departs at the office on Pedro A Pérez.

Getting Around

Havanautos ( 35-54-05; Cupet Guantánamo) is by the Servi-Cupet gas station on the way out of town toward Baracoa. If you couldn’t get a car in Santiago, you should be able to pick one up here.

35-54-05; Cupet Guantánamo) is by the Servi-Cupet gas station on the way out of town toward Baracoa. If you couldn’t get a car in Santiago, you should be able to pick one up here.

The Oro Negro gas station (cnr Los Maceos & Jesús del Sol) is another option to fill up on gas before the 150km trek east to Baracoa.

Taxis hang out around Parque Martí or you can call CubaTaxi ( 32-36-36). The bus 48 (20 centavos) runs between the center and the Hotel Guantánamo every 40 minutes or so. There are also plenty of bici-taxis.

32-36-36). The bus 48 (20 centavos) runs between the center and the Hotel Guantánamo every 40 minutes or so. There are also plenty of bici-taxis.

Return to beginning of chapter

AROUND GUANTÁNAMO US NAVAL BASE

Traditionally, it has been possible to enjoy a distant view of the base from the isolated Mirador de Malones (admission incl drink CUC$5;  8am-3pm), a Gaviota-run restaurant perched on a 320m-high hill just east of the complex. At the time of writing, visits here had been suspended with no reliable information as to when (or if) they would be reinstated. Check the current status beforehand at Hotel Guantánamo Click here or one of the Gaviota-run hotels in Baracoa.

8am-3pm), a Gaviota-run restaurant perched on a 320m-high hill just east of the complex. At the time of writing, visits here had been suspended with no reliable information as to when (or if) they would be reinstated. Check the current status beforehand at Hotel Guantánamo Click here or one of the Gaviota-run hotels in Baracoa.

Should you get lucky, the entrance to the Mirador is at a Cuban military checkpoint on the main Baracoa highway, 27km southeast of Guantánamo. You then ascend 15km up a steep, severely rutted road to the restaurant where you can peer through a telescope at the surprisingly tranquil base below. Sharp-eyed observers should look out for a US flag fluttering at the northeast gate and the sinister glassy sheen of Camp Delta. Contrary to popular belief, there is no visible sign of Cuba’s only Golden Arches.

Sleeping

Hotel Caimanera (Islazul;  9-9414; s/d with breakfast CUC$23/30;

9-9414; s/d with breakfast CUC$23/30;

) This hotel is on a hilltop at Caimanera, near the perimeter of the US Naval Base, 21km south of Guantánamo. It has peculiar rules which permit only groups of seven or more on prearranged tours with an official Cuban guide to stay and enjoy the lookout – which isn’t as good as the Mirador de Malones anyway. Ask at the Hotel Guantánamo about joining a trip.

) This hotel is on a hilltop at Caimanera, near the perimeter of the US Naval Base, 21km south of Guantánamo. It has peculiar rules which permit only groups of seven or more on prearranged tours with an official Cuban guide to stay and enjoy the lookout – which isn’t as good as the Mirador de Malones anyway. Ask at the Hotel Guantánamo about joining a trip.

Return to beginning of chapter

ZOOLÓGICO DE PIEDRAS

A surreal spectacle even by Cuban standards, the Zoológico de Piedras ( 86-51-43; admission CUC$1;

86-51-43; admission CUC$1;  9am-6pm Mon-Sat) is an animal sculpture park set amid thick foliage in the grounds of a mountain coffee farm, 20km northeast of Guantánamo. Carved quite literally out of the existing rock by sculptor Angel Iñigo Blanco starting in the late ’70s, the animal sculptures now number more than 300 and range from hippos to giant serpents. A 1km path covers the highlights. To get here you’ll need your own wheels or a taxi. Head east out of town and fork left toward Jamaica and Honduras. The ‘zoo’ is in the settlement of Boquerón.

9am-6pm Mon-Sat) is an animal sculpture park set amid thick foliage in the grounds of a mountain coffee farm, 20km northeast of Guantánamo. Carved quite literally out of the existing rock by sculptor Angel Iñigo Blanco starting in the late ’70s, the animal sculptures now number more than 300 and range from hippos to giant serpents. A 1km path covers the highlights. To get here you’ll need your own wheels or a taxi. Head east out of town and fork left toward Jamaica and Honduras. The ‘zoo’ is in the settlement of Boquerón.

Return to beginning of chapter

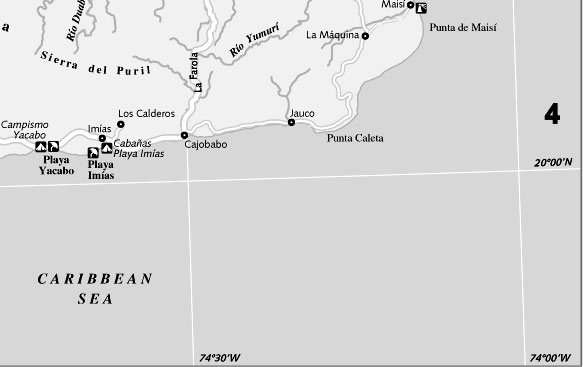

SOUTH COAST

Leaving Guantánamo in a cloud of dust, you quickly hit the long, dry coastal road to the island’s eastern extremity, Punta de Maisí. This is Cuba’s spectacular semidesert region where cacti nestle on rocky ocean terraces and prickly aloe vera poke out from the dry scrub. Several little stone beaches between Playa Yacabo and Cajobabo make refreshing pit stops for those with time to linger, while the diverse roadside scenery – punctuated at intervals by rugged purple mountains and impossibly verdant riverside oases – impresses throughout.

At the far end of deserted Playita de Cajobabo, just before the main road bends inland, there is a monument commemorating José Martí’s 1895 landing here to launch the Second War of Independence. A colorful billboard depicts the bobbing rowboat making for shore with Martí sitting calmly inside, dressed rather improbably in trademark dinner suit, not a hair out of place. It’s a good snorkeling spot, flanked by dramatic cliffs. The famous La Farola (the lighthouse road) starts here (see boxed text,). Cyclists, take a deep breath…

Sleeping & Eating

Campismo Yacabo (s/d CUC$7.5/11) This place, by the highway 10km west of Imías, has 18 well-maintained cabins overlooking the sea near the mouth of the river. The cabins sleep four to six people and make a great beach getaway for groups on a budget. It’s supposed to accept foreigners, but check ahead.

Cabañas Playa Imías (1-2 people CUC$10;  ) This place, 2km east of Imías midway between Guantánamo and Baracoa, is near a long dark beach that drops off quickly into deep water. The 15 cement cabins have baths, fridges and TVs. It doesn’t guarantee foreign admission but, as ever in Cuba, the rules are flexible.

) This place, 2km east of Imías midway between Guantánamo and Baracoa, is near a long dark beach that drops off quickly into deep water. The 15 cement cabins have baths, fridges and TVs. It doesn’t guarantee foreign admission but, as ever in Cuba, the rules are flexible.

Return to beginning of chapter

PUNTA DE MAISÍ

From Cajobabo, the coastal road continues 51km northeast to La Máquina. As far as Jauco, the road is good; thereafter it’s not so good. Coming from Baracoa to La Máquina (55km), it’s a good road as far as Sabana, then rough in places from Sabana to La Máquina. Either way, La Máquina is the starting point of the very rough 13km track down to Punta de Maisí; it’s best covered in a 4WD.

This is Cuba’s easternmost point and there’s a lighthouse (1862) and a small fine white-sand beach. You can see Haiti 70km away on a clear day.

At the time of writing the Maisí area was designated a military zone and not open to travelers.

Return to beginning of chapter

BOCA DE YUMURÍ

Five kilometers south of Baracoa a road branches left off La Farola and travels 28km along the coast to Boca de Yumurí at the mouth of Río Yumurí. Near the bridge over the river is the Túnel de los Alemanes (German Tunnel), an amazing natural arch of trees and foliage. Though lovely, the dark sand beach here has become the day trip from Baracoa. Hustlers hard-sell fried fish meals, while other people peddle colorful land snails called polymitas. They have become rare as a result of being harvested wholesale for tourists, so refuse all offers. From the end of the beach a boat taxi (CUC$2) heads upstream to where the steep river banks narrow into a haunting natural gorge.

Boca de Yumurí makes a superb bike jaunt from Baracoa (56km round-trip): hot, but smooth and flat with great views and many potential stopovers (try Playa Bariguá at Km 25). You can arrange bikes in Baracoa – ask at your casa particular. Taxis will also take you here from Baracoa, or you can organize an excursion with Cubatur (CUC$22; see right).

Return to beginning of chapter

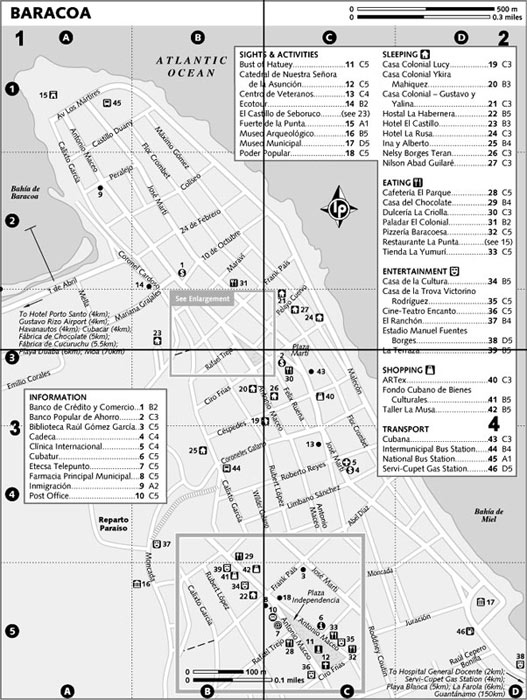

BARACOA

pop 42,285

Take a pinch of Tolkein, a dash of Gabriel García Márquez, mix in a large cup of 1960s psychedelia and temper with a tranquilizing dose of Cold War–era socialism. Leave to stand for 400 years in a geographically isolated tropical wilderness with little or no contact with the outside world. The result: Baracoa – Cuba’s weirdest, wildest, zaniest and most unique settlement that materializes like a surreal apparition after the long dry plod along Guantánamo’s southern coast.

Cut off by land and sea for nearly half a millennium, Cuba’s oldest city is, for most visitors, one of its most interesting. Founded in 1511 by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, Baracoa is a visceral place of fickle weather and haunting legends. After being semiabandoned in the mid-16th century, the town became a Cuban Siberia where rebellious revolutionaries were sent as prisoners. In the early 19th century French planters crossed the 70km-wide Windward Passage from Haiti and began farming the local staples of coconut, cocoa and coffee in the mountains and the economic wheels began to turn.

Baracoa developed in relative isolation from the rest of Cuba until the opening of La Farola (see boxed text,) in 1964, a factor that has strongly influenced its singular culture and traditions. Today its premier attractions include trekking up mysterious El Yunque, the region’s signature flat-topped mountain, or indulging in some inspired local cooking using ingredients and flavors found nowhere else in Cuba.

Orientation

Gustavo Rizo Airport (airport code BCA) is 1km off the road to Moa beside Hotel Puerto Santo, 4km from central Baracoa. Baracoa’s two bus stations are on opposite sides of town. There are three good hotels in or near the old town and another one next to the airport. Most of Baracoa can be explored on foot, but a bicycle is useful for visiting nearby beaches and rural pockets.

Information

INTERNET ACCESS & TELEPHONE

- Etecsa Telepunto (cnr Antonio Maceo & Rafael Trejo; per hr CUC$6;

8:30am-7:30pm) Internet and international calls.

8:30am-7:30pm) Internet and international calls.

LIBRARIES

- Biblioteca Raúl Gómez García (José Martí No 130;

8am-noon & 2-9pm Mon-Fri, 8am-4pm Sat)

8am-noon & 2-9pm Mon-Fri, 8am-4pm Sat)

MEDIA

- Radio CMDX ‘La Voz del Toa’ Broadcasts over 650AM.

MEDICAL SERVICES

- Clínica Internacional (

64-10-37; cnr José Martí & Roberto Reyes;

64-10-37; cnr José Martí & Roberto Reyes;  24hr) A new place that treats foreigners; there’s also a hospital 2km out of town on the road to Guantánamo.

24hr) A new place that treats foreigners; there’s also a hospital 2km out of town on the road to Guantánamo. - Farmacia Principal Municipal (Antonio Maceo No 132;

24hr)

24hr)

MONEY

- Banco de Crédito y Comercio (

64-27-71; Antonio Maceo No 99;

64-27-71; Antonio Maceo No 99;  8am-2:30pm Mon-Fri)

8am-2:30pm Mon-Fri) - Banco Popular de Ahorro (José Martí No 166;

8-11:30am & 2-4:30pm Mon-Fri) Cashes traveler’s checks.

8-11:30am & 2-4:30pm Mon-Fri) Cashes traveler’s checks. - Cadeca (

64-33-04; José Martí No 241)

64-33-04; José Martí No 241)

POST

- Post office (Antonio Maceo No 136;

8am-8pm)

8am-8pm)

TRAVEL AGENCIES

- Cubatur (

64-53-06; Antonio Maceo;

64-53-06; Antonio Maceo;  8am-noon & 2-5pm Mon-Fri) Helpful office that organizes tours to El Yunque and Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt.

8am-noon & 2-5pm Mon-Fri) Helpful office that organizes tours to El Yunque and Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt. - Ecotur (

64-36-65; Coronel Cardoso No 24;

64-36-65; Coronel Cardoso No 24;  9am-5pm) Organizes nature tours to Duaba, Toa and Yumurí Rivers.

9am-5pm) Organizes nature tours to Duaba, Toa and Yumurí Rivers.

Sights & Activities

IN TOWN

Crying out for a major renovation, the rapidly disintegrating Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Antonio Maceo No 152) was built in 1833 on the site of a much older church. Its most famous artifact is the priceless Cruz de La Parra, a wooden cross said to have been erected by Columbus near Baracoa in 1492. Carbon dating has authenticated the cross’ age (it dates from the late 1400s), but has indicated that it was originally made out of indigenous Cuban wood, thus disproving the legend that Columbus brought the cross from Europe. The church was closed at the time of writing and the cross was being displayed in the last house on Calle Antonio Maceo, behind the church to the right.

Facing the cathedral is the Bust of Hatuey, a rebellious Indian cacique (chief) who fell out with the Spanish and was burned at the stake near Baracoa in 1512 after refusing to convert to Catholicism. Also on triangular Plaza Independencia (this being Baracoa, they couldn’t have a square plaza) is the neoclassical Poder Popular (Antonio Maceo No 137), a municipal government building which you can admire from the outside.

The Centro de Veteranos (José Martí No 216; admission free) displays photos of those who perished in the 1959 Revolution and in the barely talked-about conflict in Angola.

Baracoa is protected by a trio of muscular Spanish forts. The Fuerte Matachín (1802) at the southern entrance to town, now houses the Museo Municipal (cnr José Martí & Malecón; admission CUC$1;  8am-noon & 2-6pm). Though small, this museum showcases an engaging chronology of Cuba’s oldest settlement including polymita snail shells, the story of Che Guevara and the chocolate factory, and exhibits relating to pouty Magdalena Menasse (née Rovieskuya, ‘La Rusa’) after whom Alejo Carpentier based his famous book, La Consagración de la Primavera (The Rite of Spring).

8am-noon & 2-6pm). Though small, this museum showcases an engaging chronology of Cuba’s oldest settlement including polymita snail shells, the story of Che Guevara and the chocolate factory, and exhibits relating to pouty Magdalena Menasse (née Rovieskuya, ‘La Rusa’) after whom Alejo Carpentier based his famous book, La Consagración de la Primavera (The Rite of Spring).

A second Spanish fort, the Fuerte de la Punta, has watched over the harbor entrance at the other end of town since 1803. Today it’s a Gaviota restaurant that was temporarily closed after 2008’s Hurricane Ike.

Baracoa’s third fort, El Castillo de Seboruco, begun by the Spanish in 1739 and finished by the Americans in 1900, is now Hotel El Castillo. There’s an excellent view of El Yunque’s flat top over the shimmering swimming pool. A steep stairway at the southwest end of Calle Frank País climbs directly up.

Baracoa’s newest and most impressive museum is the Museo Arqueológico (Moncada; admission CUC$3;  8am-5pm), situated in Las Cuevas del Paraíso 800m southeast of the Hotel El Castillo. The exhibits here are showcased in a series of caves that once acted as Taíno burial chambers. Among nearly 2000 authentic Taíno pieces are unearthed skeletons, ceramics, 3000-year-old petroglyphs and a replica of the Ídolo de Tabaco, a sculpture found in Maisí in 1903 that is considered to be one of the most important Taíno finds in the Caribbean. One of the staff will enthusiastically show you around.

8am-5pm), situated in Las Cuevas del Paraíso 800m southeast of the Hotel El Castillo. The exhibits here are showcased in a series of caves that once acted as Taíno burial chambers. Among nearly 2000 authentic Taíno pieces are unearthed skeletons, ceramics, 3000-year-old petroglyphs and a replica of the Ídolo de Tabaco, a sculpture found in Maisí in 1903 that is considered to be one of the most important Taíno finds in the Caribbean. One of the staff will enthusiastically show you around.

SOUTHEAST OF TOWN

Southeast of town are a couple of magical hikes that can only be done on foot. Passing the Fuerte Matachín, hike southeast past the baseball stadium and along the dark-sand beach for about 20 minutes to a rickety wooden bridge over the Río Miel. After crossing the bridge turn left, and follow a track up through a cluster of rustic houses to another junction. Turn left again and continue along the vehicle track until the houses clear and you see a fainter single-track path leading off left to Playa Blanca, an idyllic spot for a picnic.

Staying straight on the track, you’ll come to a trio of wooden homesteads. The third of these houses belongs to the Fuentes family. Do not continue alone past this point as you are entering a military zone. For a donation (CUC$3 to CUC$5 per person), Señor Fuentes will lead you on a hike to his family finca, where you can stop for coffee, coconuts and tropical fruit. Further on he’ll show you the Cueva de Aguas, a cave with a sparkling, freshwater swimming hole inside, and tracking back up the hillside (a sure pair of feet are required for this bit) you’ll come to an archaeological trail with some more caves and marvelous views over the ocean.

NORTHWEST OF TOWN

Heading northwest on the Moa road, take the Hotel Porto Santo and airport turning (right) and continue for 2km past the airport runway to Playa Duaba, a black-sand beach at the mouth of the river where Antonio Maceo, Flor Crombet and a score of men landed in 1895 to start the Second War of Independence. There’s a memorial monument here, but the beach itself is nothing special and the sand flies can be ferocious.

The delicious sweet smells filling the air in this neck of the woods are concocted in the famous Fábrica de Chocolate, 1km past the airport turnoff, opened not by Willy Wonka but by Che Guevara in 1963. Half a kilometer further on you’ll pass the equally tempting Fábrica de Cucuruchu where you can buy Baracoa’s sweetest treat, wrapped in an environmentally friendly palm frond, for a few centavos.

Tours

Organized tours are a good way to view Baracoa’s hard-to-reach outlying sights, and the Cubatur office Click here on Plaza Independencia can book most of them. Highlights include: El Yunque (CUC$18), Playa Maguana (CUC$18), Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt (CUC$28), Río Toa (CUC$11) and Boca de Yumurí (CUC$22).

Festivals & Events

During the first week of April, Baracoa commemorates the landing of Antonio Maceo at Duaba on April 1, 1895, with a raucous Carnaval along the Malecón. Every Saturday night, Calle Antonio Maceo is closed off for Noche Baracuensa, when food, drink and music take over.

Sleeping

CASAS PARTICULARES

Casa Colonial – Gustavo & Yalina ( 64-25-36; Flor Crombet No 125 btwn Frank País & Pelayo Cuervo; r CUC$15-20;

64-25-36; Flor Crombet No 125 btwn Frank País & Pelayo Cuervo; r CUC$15-20;  ) This grand house was built in 1898 by a French sugar baron from Marseille, an esteemed ancestor of the current residents. The big windowless rooms have antique furnishings, and culinary treats include local freshwater prawns and hot (Baracoan) chocolate for breakfast.

) This grand house was built in 1898 by a French sugar baron from Marseille, an esteemed ancestor of the current residents. The big windowless rooms have antique furnishings, and culinary treats include local freshwater prawns and hot (Baracoan) chocolate for breakfast.

Casa Colonial Lucy ( 64-35-48; Céspedes No 29 btwn Rubert López & Antonio Maceo; r CUC$20;

64-35-48; Céspedes No 29 btwn Rubert López & Antonio Maceo; r CUC$20;  ) A perennial favorite, Casa Lucy – which dates from 1840 – has a lovely local character with patios, porches and flowering begonias. There are two rooms as well as terraces here on different levels and the atmosphere is quiet and secluded. Lucy’s son is trilingual and offers salsa lessons and massage.

) A perennial favorite, Casa Lucy – which dates from 1840 – has a lovely local character with patios, porches and flowering begonias. There are two rooms as well as terraces here on different levels and the atmosphere is quiet and secluded. Lucy’s son is trilingual and offers salsa lessons and massage.

Nelsy Borges Teran ( 64-35-69; Antonio Maceo No 171 btwn Ciro Frías & Céspedes; r CUC$20;

64-35-69; Antonio Maceo No 171 btwn Ciro Frías & Céspedes; r CUC$20;  ) The food is better than the room – and the room ain’t half bad. You’ll have no culinary worries at Nelsy’s with plenty of vegetarian options and adventurous deserts. The rooms have TV and stocked fridge (including chocolate) and there’s a great terrace upstairs with rocking chairs overlooking the street.

) The food is better than the room – and the room ain’t half bad. You’ll have no culinary worries at Nelsy’s with plenty of vegetarian options and adventurous deserts. The rooms have TV and stocked fridge (including chocolate) and there’s a great terrace upstairs with rocking chairs overlooking the street.

Casa Colonial Ykira Mahiquez ( 64-24-66; Antonio Maceo No 168A btwn Ciro Frías & Céspedes; r CUC$20;

64-24-66; Antonio Maceo No 168A btwn Ciro Frías & Céspedes; r CUC$20;  ) Welcoming and hospitable, Ykira is Baracoa’s hostess with the mostess and serves a mean dinner made with homegrown herbs. Her cozy house is one block from the cathedral and full of local charm.

) Welcoming and hospitable, Ykira is Baracoa’s hostess with the mostess and serves a mean dinner made with homegrown herbs. Her cozy house is one block from the cathedral and full of local charm.

Ina & Alberto ( 64-27-29; Calixto García No 158; r CUC$20-25;

64-27-29; Calixto García No 158; r CUC$20-25;  ) Perched on a hill at the back of town, this place has good views, two terraces and private entry. Alberto is something of a local guide who knows the region like the back of his hand.

) Perched on a hill at the back of town, this place has good views, two terraces and private entry. Alberto is something of a local guide who knows the region like the back of his hand.

Nilson Abad Guilaré ( 64-31-23; nilson@santiagocaribe.com; Flor Crombet No 143 btwn Ciro Frías & Pelayo Cuervo; r CUC$25;

64-31-23; nilson@santiagocaribe.com; Flor Crombet No 143 btwn Ciro Frías & Pelayo Cuervo; r CUC$25;  ) Nilson’s a real gent who keeps what must be one of the cleanest houses in Cuba. This fantastic self-contained apartment has a huge bathroom, kitchen access and roof terrace with sea views. The fish dinners with coconut sauce are to die for.

) Nilson’s a real gent who keeps what must be one of the cleanest houses in Cuba. This fantastic self-contained apartment has a huge bathroom, kitchen access and roof terrace with sea views. The fish dinners with coconut sauce are to die for.

HOTELS

Hotel El Castillo (Gaviota;  64-51-64; Loma del Paraíso; s/d CUC$42/58;

64-51-64; Loma del Paraíso; s/d CUC$42/58;

) You could recline like a colonial-era conquistador in this historic place housed in the hilltop Castillo de Seboruco, except that conquistadors didn’t have access to swimming pools, satellite TV or a room maid who folds towels into ships, swans and other advanced forms of origami. While the 34 rooms at this fine Gaviota-run hotel might be a little dilapidated and damp, the jaw-dropping El Yunque views and all-pervading Baracoan friendliness more than make up for it.

) You could recline like a colonial-era conquistador in this historic place housed in the hilltop Castillo de Seboruco, except that conquistadors didn’t have access to swimming pools, satellite TV or a room maid who folds towels into ships, swans and other advanced forms of origami. While the 34 rooms at this fine Gaviota-run hotel might be a little dilapidated and damp, the jaw-dropping El Yunque views and all-pervading Baracoan friendliness more than make up for it.

Hotel Porto Santo (Gaviota;  64-51-06; Carretera del Aeropuerto; s/d CUC$42/58;

64-51-06; Carretera del Aeropuerto; s/d CUC$42/58;

) On the bay where Columbus, allegedly, planted his first cross, this well-integrated low-rise hotel has the feel of a small resort. Situated 4km from the town center and 200m from the airport, there are 36 more-than-adequate rooms all within earshot of the sea. Lie awake with the windows open and let the ethereal essence of Baracoa transport you. A steep stairway leads down to a tiny, wave-lashed beach.

) On the bay where Columbus, allegedly, planted his first cross, this well-integrated low-rise hotel has the feel of a small resort. Situated 4km from the town center and 200m from the airport, there are 36 more-than-adequate rooms all within earshot of the sea. Lie awake with the windows open and let the ethereal essence of Baracoa transport you. A steep stairway leads down to a tiny, wave-lashed beach.

Hotel La Rusa (Gaviota;  64-30-11; Máximo Gómez No 161; r CUC$49;

64-30-11; Máximo Gómez No 161; r CUC$49;  ) Khrushchev wasn’t the first Russian to hedge his bets with Fidel Castro. Long before the Bay of Pigs sent the Cubans running into the arms of the Soviets, Russian émigré Magdalena Rovieskuya was posting aid to Castro’s rebels up in the Sierra Maestra. Rovieskuya – known affectionately as ‘La Rusa’ – first came to Baracoa in the 1930s where she built a 12-room hotel and quickly became a local celebrity receiving such esteemed guests as Errol Flynn, Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. After her death in 1978, La Rusa became a more modest government-run joint that was all but washed away in Hurricane Ike. It was undergoing a thorough renovation at the time of writing.

) Khrushchev wasn’t the first Russian to hedge his bets with Fidel Castro. Long before the Bay of Pigs sent the Cubans running into the arms of the Soviets, Russian émigré Magdalena Rovieskuya was posting aid to Castro’s rebels up in the Sierra Maestra. Rovieskuya – known affectionately as ‘La Rusa’ – first came to Baracoa in the 1930s where she built a 12-room hotel and quickly became a local celebrity receiving such esteemed guests as Errol Flynn, Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. After her death in 1978, La Rusa became a more modest government-run joint that was all but washed away in Hurricane Ike. It was undergoing a thorough renovation at the time of writing.

Hostal La Habanera (Gaviota;

Hostal La Habanera (Gaviota;  64-23-37; Antonio Maceo No 126; r CUC$49;

64-23-37; Antonio Maceo No 126; r CUC$49;  ) Atmospheric and inviting in a way only Baracoa can muster, La Habanera sits in a restored pastel-pink colonial mansion where the cries of passing street hawkers compete with an effusive mix of hip-gyrating music emanating from the Casa de la Cultura next door. The four front bedrooms share a street-facing balcony replete with tiled floor and rocking chairs, while the downstairs lobby boasts a bar, the 1511 restaurant, and an interesting selection of local books.

) Atmospheric and inviting in a way only Baracoa can muster, La Habanera sits in a restored pastel-pink colonial mansion where the cries of passing street hawkers compete with an effusive mix of hip-gyrating music emanating from the Casa de la Cultura next door. The four front bedrooms share a street-facing balcony replete with tiled floor and rocking chairs, while the downstairs lobby boasts a bar, the 1511 restaurant, and an interesting selection of local books.

Eating

After the dull monotony of just about everywhere else, eating in Baracoa is a full-on sensory experience. Cooking here is creative, tasty and – above all – different. Local delicacies include cucuruchu (grated coconut mixed with sugar, honey and guava, wrapped in a palm frond), fish with coconut sauce, bacán (pulped plantain and coconut milk) and teti (a tiny red fish indigenous to the Río Toa). To experience the real deal, eat in your casa particular.

PALADARES

Paladar El Colonial (José Martí No 123; mains CUC$10;  lunch & dinner) The town’s only surviving paladar has been knocking out good food for years with an exotic Baracoan twist. Still run out of a handsome wooden clapboard house on Calle José Martí, the menu has become a bit more limited in recent times (less octopus and more chicken), though you still get the down-to-earth service and the delicious coconut sauce.

lunch & dinner) The town’s only surviving paladar has been knocking out good food for years with an exotic Baracoan twist. Still run out of a handsome wooden clapboard house on Calle José Martí, the menu has become a bit more limited in recent times (less octopus and more chicken), though you still get the down-to-earth service and the delicious coconut sauce.

RESTAURANTS

Casa del Chocolate (Antonio Maceo No 123;  7:20am-11pm) It’s enough to make even Willy Wonka wonder. You’re sitting next to a chocolate factory but, more often than not, there’s none to be had in this bizarre little casa just off the main square. The quickest way to check out Baracoa’s on-off supply situation is to stick your head around the door and utter the word ‘chocolate’ to one of the bored-looking waitresses. No hay equals ‘no,’ a faint nod equals ‘yes.’ On a good day it sells chocolate ice cream and the hot stuff in mugs. For all its foibles, it’s a Baracoa rite of passage.

7:20am-11pm) It’s enough to make even Willy Wonka wonder. You’re sitting next to a chocolate factory but, more often than not, there’s none to be had in this bizarre little casa just off the main square. The quickest way to check out Baracoa’s on-off supply situation is to stick your head around the door and utter the word ‘chocolate’ to one of the bored-looking waitresses. No hay equals ‘no,’ a faint nod equals ‘yes.’ On a good day it sells chocolate ice cream and the hot stuff in mugs. For all its foibles, it’s a Baracoa rite of passage.

Pizzería Baracoesa (Antonio Maceo No 155) A recent renovation (ie new tablecloths) have upped the ante a little at this peso place, but it’s still got a long way to go to tempt you out of your casa particular.

Cafetería El Parque (Antonio Maceo No 142;  24hr) This open terrace gets regularly drenched in those familiar Baracoa rain showers, but that doesn’t seem to detract from its popularity. The favored meeting place of just about everyone in town, you’re bound to end up here at some point tucking into spaghetti and pizza as you watch the world go by.

24hr) This open terrace gets regularly drenched in those familiar Baracoa rain showers, but that doesn’t seem to detract from its popularity. The favored meeting place of just about everyone in town, you’re bound to end up here at some point tucking into spaghetti and pizza as you watch the world go by.

Restaurante La Punta (Fuerte de la Punta;  10am-11pm) In an old fort overlooking the Atlantic, this historic restaurant now run by Gaviota was temporarily closed at the time of writing after the havoc wreaked by Hurricane Ike. It was due to reopen in 2009.

10am-11pm) In an old fort overlooking the Atlantic, this historic restaurant now run by Gaviota was temporarily closed at the time of writing after the havoc wreaked by Hurricane Ike. It was due to reopen in 2009.

GROCERIES

Tienda La Yumurí (Antonio Maceo No 149;  8:30am-noon & 1:30-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) Get in line for the good selection of groceries here.

8:30am-noon & 1:30-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) Get in line for the good selection of groceries here.

Dulcería La Criolla (José Martí No 178) This place sells bread, pastries and – when it feels like it – the famous Baracoan chocolate.

Drinking & Entertainment

Casa de la Trova Victorino Rodríguez (Antonio Maceo No 149A) Cuba’s smallest, zaniest, wildest and most atmospheric casa de la trova (trova house) rocks nightly to the voodoolike rhythms of changüí-son. Order a mojito in a jam jar and sit back and enjoy the show.

Casa de la Trova Victorino Rodríguez (Antonio Maceo No 149A) Cuba’s smallest, zaniest, wildest and most atmospheric casa de la trova (trova house) rocks nightly to the voodoolike rhythms of changüí-son. Order a mojito in a jam jar and sit back and enjoy the show.

El Ranchón (admission CUC$1;  from 9pm) Atop a long flight of stairs at the western end of Coroneles Galano, El Ranchón mixes an exhilarating hilltop setting with taped disco and salsa music and legions of resident jineteras (women who attach themselves to male foreigners for monetary or material gain). Maybe that’s why it’s so insanely popular. Watch your step on the way down – it’s a scary 146-step drunken tumble.

from 9pm) Atop a long flight of stairs at the western end of Coroneles Galano, El Ranchón mixes an exhilarating hilltop setting with taped disco and salsa music and legions of resident jineteras (women who attach themselves to male foreigners for monetary or material gain). Maybe that’s why it’s so insanely popular. Watch your step on the way down – it’s a scary 146-step drunken tumble.

Casa de la Cultura ( 64-23-49; Antonio Maceo No 124 btwn Frank País & Maraví) This venue does a wide variety of shows including some good rumba incorporating the textbook Cuban styles of guaguancó, yambú and columbia (subgenres of rumba). Go prepared for mucho audience participation.

64-23-49; Antonio Maceo No 124 btwn Frank País & Maraví) This venue does a wide variety of shows including some good rumba incorporating the textbook Cuban styles of guaguancó, yambú and columbia (subgenres of rumba). Go prepared for mucho audience participation.

La Terraza (Antonio Maceo btwn Maraví & Frank País; admission CUC$1;  9pm-2am Mon-Thu, 9pm-4am Fri-Sun) A rooftop disco with occasional hot salsa septets that you’ll hear all over town.

9pm-2am Mon-Thu, 9pm-4am Fri-Sun) A rooftop disco with occasional hot salsa septets that you’ll hear all over town.

Cine-Teatro Encanto (Antonio Maceo No 148) The town’s only cinema is in front of the cathedral. It looks disused but you’ll probably find it’s open.

From October to April, baseball games are held at the Estadio Manuel Fuentes Borges, southeast along the beach from the Museo Municipal.

Shopping

Good art is easy to find in Baracoa and, like most things in this whimsical seaside town, it has its own distinctive flavor.

Fondo Cubano de Bienes Culturales (Antonio Maceo No 120;  9am-5pm Mon-Fri, 9am-noon Sat & Sun) This shop sells Hatuey woodcarvings and T-shirts with indigenous designs.

9am-5pm Mon-Fri, 9am-noon Sat & Sun) This shop sells Hatuey woodcarvings and T-shirts with indigenous designs.

ARTex (José Martí btwn Céspedes & Coroneles Galano) For the usual tourist fare check out this place.

Taller La Musa (Antonio Maceo No 124) Call by this place opposite the Casa de la Cultura where you can seek out typically imaginative Baracoan art.

Getting There & Away

The closest train station is in Guantánamo, 150km southwest.

AIR

Gustavo Rizo Airport ( 64-53-76) is 4km northwest of the town, just behind the Hotel Porto Santo. Cubana (

64-53-76) is 4km northwest of the town, just behind the Hotel Porto Santo. Cubana ( 64-21-71; José Martí No 181;

64-21-71; José Martí No 181;  8am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Fri) has two weekly flights from Havana to Baracoa (CUC$135 one-way, Thursday and Sunday).

8am-noon & 2-4pm Mon-Fri) has two weekly flights from Havana to Baracoa (CUC$135 one-way, Thursday and Sunday).

Be aware that the planes and buses out of Baracoa are sometimes fully booked, so don’t come here on a tight schedule without outbound reservations.

BUS & TRUCK

The national bus station ( 64-36-70; cnr Av Los Mártires & José Martí) has Víazul (www.viazul.com) buses to Guantánamo (CUC$10, three hours), continuing to Santiago de Cuba (CUC$16, five hours) daily at 2:15pm. Bus tickets can be reserved in advance through Cubatur (

64-36-70; cnr Av Los Mártires & José Martí) has Víazul (www.viazul.com) buses to Guantánamo (CUC$10, three hours), continuing to Santiago de Cuba (CUC$16, five hours) daily at 2:15pm. Bus tickets can be reserved in advance through Cubatur ( 64-53-06; Antonio Maceo No 181) for a CUC$5 commission, or you can usually stick your name on the list a day or so beforehand.

64-53-06; Antonio Maceo No 181) for a CUC$5 commission, or you can usually stick your name on the list a day or so beforehand.

The intermunicipal bus station (cnr Coroneles Galano & Calixto García) has two or three trucks a day to Moa (90 minutes, departures from 6am) and Guantánamo (four hours, departures from 2am). Bank on big crowds and bad roads. Prices are a few Cuban pesos.

Getting Around

The best way to get to and from the airport is by taxi (CUC$2) or bici-taxi (CUC$1), if you’re traveling light.

There’s a helpful Havanautos ( 64-53-44) car-rental office at the airport. Cubacar (

64-53-44) car-rental office at the airport. Cubacar ( 64-51-55) is at the Hotel Porto Santo. The Servi-Cupet gas station (José Martí;

64-51-55) is at the Hotel Porto Santo. The Servi-Cupet gas station (José Martí;  24hr) is at the entrance to town and also 4km from the center, on the road to Guantánamo. If you’re driving to Havana, note that the northern route through Moa and Holguín is fastest but the road disintegrates rapidly after Playa Maguana. Most locals prefer the La Farola route.

24hr) is at the entrance to town and also 4km from the center, on the road to Guantánamo. If you’re driving to Havana, note that the northern route through Moa and Holguín is fastest but the road disintegrates rapidly after Playa Maguana. Most locals prefer the La Farola route.

Bici-taxis around Baracoa should charge five pesos a ride, but they often ask 10 to 15 pesos from foreigners.

Most casas particulares will be able to procure you a bicycle for CUC$3 per day. The ultimate bike ride is the 20km ramble down to Playa Maguana, one of the most scenic roads in Cuba. Lazy daisies can rent mopeds for CUC$24 either at Cafetería El Parque (opposite) or Hotel El Castillo.

Return to beginning of chapter

NORTHWEST OF BARACOA

Sights & Activities

The Finca Duaba ( noon-4pm Tue-Sun), 5km out of Baracoa on the road to Moa and then 1km inland, offers a fleeting taste of the Baracoan countryside. It’s a verdant farm surrounded with profuse tropical plants and embellished with a short Cacao (cocoa) trail that explains the history and characteristics of the plant with some interactive displays. There’s also a good ranchón-style restaurant and the opportunity to swim in the Río Duaba. A bici-taxi can drop you at the road junction.

noon-4pm Tue-Sun), 5km out of Baracoa on the road to Moa and then 1km inland, offers a fleeting taste of the Baracoan countryside. It’s a verdant farm surrounded with profuse tropical plants and embellished with a short Cacao (cocoa) trail that explains the history and characteristics of the plant with some interactive displays. There’s also a good ranchón-style restaurant and the opportunity to swim in the Río Duaba. A bici-taxi can drop you at the road junction.

The Río Toa, 10km northwest of Baracoa, is the third-longest river on the north coast of Cuba and the country’s most voluminous. It is also an important bird and plant habitat. Cocoa trees and the ubiquitous coconut palm are grown in the Valle de Toa. A vast hydroelectric project on the Río Toa was abandoned after a persuasive campaign led by the Fundación de la Naturaleza y El Hombre convinced authorities it would do irreparable ecological damage; engineering and economic reasons also played a part. Rancho Toa is a Palmares restaurant reached via a right-hand turnoff just before the Toa Bridge. You can organize boat or kayak trips here for CUC$3 to CUC$10 and watch acrobatic Baracoans scale cocotero (coconut palm). A traditional Cuban feast of whole roast pig is available if you can rustle up enough people (eight usually).

Most of this region lies within the Cuchillas de Toa Unesco Biosphere Reserve, an area of 2083 sq km that incorporates the Alejandro de Humboldt World Heritage Site. This region contains the largest rainforest in Cuba, with trees exhibiting many precious woods, and has a high number of endemic species.

Baracoa’s rite of passage is the 8km (up and down) hike to El Yunque. At 575m it’s not Kilimanjaro, but the views from the summit and the flora and birdlife along the way are stupendous. Cubatur ( 64-53-06; José Martí No 181, Baracoa) offers this tour almost daily (CUC$18 per person, minimum two people). The fee covers admission, guide, transport and a sandwich. The hike is hot (bring sufficient water) and usually muddy. It starts from a campismo 3km past the Finca Duaba (4km from the Baracoa–Moa road). Bank on seeing tocororo (Cuba’s national bird), zunzún (the world’s smallest bird), butterflies and polymitas.

64-53-06; José Martí No 181, Baracoa) offers this tour almost daily (CUC$18 per person, minimum two people). The fee covers admission, guide, transport and a sandwich. The hike is hot (bring sufficient water) and usually muddy. It starts from a campismo 3km past the Finca Duaba (4km from the Baracoa–Moa road). Bank on seeing tocororo (Cuba’s national bird), zunzún (the world’s smallest bird), butterflies and polymitas.

On Playa Maguana snorkeling is available from boats at a nearby reef. There’s no hire kiosk as such; the local boatman just works the strip.

Sleeping & Eating

Villa Maguana (Gaviota;

Villa Maguana (Gaviota;  64-53-72; Carretera a Moa; s/d CUC$60/75;

64-53-72; Carretera a Moa; s/d CUC$60/75;

) Good old Gaviota renovated this delightful place, 22km north of Baracoa, adding a trio of rustic wooden villas to the original four-room building. Environmental foresight has meant that it still retains its famously dreamy setting above a bite-sized scoop of sand guarded by two rocky promontories. There’s a restaurant and some less rustic luxuries in the rooms such as satellite TV, fridge and air-con.

) Good old Gaviota renovated this delightful place, 22km north of Baracoa, adding a trio of rustic wooden villas to the original four-room building. Environmental foresight has meant that it still retains its famously dreamy setting above a bite-sized scoop of sand guarded by two rocky promontories. There’s a restaurant and some less rustic luxuries in the rooms such as satellite TV, fridge and air-con.

The main strip of Playa Maguana is served by a small Palmares snack bar ( 9am-5pm) that sells cold drinks, fried chicken and sandwiches. The local fishermen have been known to fire up an excellent fish barbecue.

9am-5pm) that sells cold drinks, fried chicken and sandwiches. The local fishermen have been known to fire up an excellent fish barbecue.

Return to beginning of chapter

PARQUE NACIONAL ALEJANDRO DE HUMBOLDT

‘Unmatched in the Caribbean’ is a phrase often used to describe this most dramatic and diverse of Cuban national parks, named after German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt who first came here in 1801. The accolade is largely true. Designated a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2001, Humboldt’s steep pine-clad mountains and creeping morning mists protect an unmatched ecosystem that is, according to Unesco, ‘one of the most biologically diverse tropical island sites on earth.’ Perched above the Bahía de Taco, 40km northwest of Baracoa, lie 594 sq km of pristine forest and 2641 hectares of lagoon and mangroves. With 1000 flowering plant species and 145 types of fern, it is far and away the most diverse plant habitat in the entire Caribbean. Due to the toxic nature of the underlying rocks in the area, plants have been forced to adapt in order to survive. As a result, endemism in the area is high. Seventy percent of the plants found here are endemic, as are many vertebrates and invertebrates. Several endangered species also survive, including Cuban Amazon parrots, hook-billed kites and – arguably – the ivory-billed woodpecker (see boxed text, opposite). Lauded for its unique evolutionary processes, the park is heavily protected and acts as a paradigm for Cuba’s environmental protection efforts elsewhere.

Activities

The park contains a small visitors center ( 38-14-31) staffed with biologists plus a network of trails leading to waterfalls, a mirador (lookout) and a massive karst system with caves around the Farallones de Moa. Three trails are currently open to the public and take in only a tiny segment of the park’s 594 sq km. Typically, you can’t just wander around on your own. The available hikes are: Balcón de Iberia, at 5km the park’s most challenging loop; El Recrea, a 2km stroll around the bay; and the Bahía de Taco circuit, which incorporates a boat tour (with a manatee-friendly motor developed by scientists here) through the mangroves and the bay, plus the 2km hike. Each option is accompanied by a highly professional guide. Prices range from CUC$5 to CUC$10, depending on the hike, but it’s far better to organize an excursion through Cubatur in Baracoa.

38-14-31) staffed with biologists plus a network of trails leading to waterfalls, a mirador (lookout) and a massive karst system with caves around the Farallones de Moa. Three trails are currently open to the public and take in only a tiny segment of the park’s 594 sq km. Typically, you can’t just wander around on your own. The available hikes are: Balcón de Iberia, at 5km the park’s most challenging loop; El Recrea, a 2km stroll around the bay; and the Bahía de Taco circuit, which incorporates a boat tour (with a manatee-friendly motor developed by scientists here) through the mangroves and the bay, plus the 2km hike. Each option is accompanied by a highly professional guide. Prices range from CUC$5 to CUC$10, depending on the hike, but it’s far better to organize an excursion through Cubatur in Baracoa.

Sleeping

Lodging is periodically available at the bare-bones Campismo Bahía de Taco. Phone ahead or inquire at Hostal La Habanera in Baracoa.

Getting There & Away

You can arrange a tour through an agency in Baracoa or get here independently. The road is rough but passable in a hire car if driven with care.