As the Titanic drew away from the wharf to begin her only voyage, a common emotion quickened the thousands who were aboard her. Grimy slaves who worked and withered deep down in the glaring heat of her boiler rooms, on her breezy decks men of achievement and fame and millionaire pleasure seekers for whom the boat provided countless luxuries, in the steerage hordes of emigrants huddled in straited quarters but with their hearts fired for the new free land of hope; these, and also he whose anxious office placed him high above all—charged with the keeping of all of their lives—this care-furrowed captain on the bridge, his many-varied passengers, and even the remotest menial of his crew, experienced alike a glow of triumph born of pride in the enormous, wonderful new ship that carried them.

For she was the biggest boat that ever had been in the world. She implied the utmost stretch of construction, the furthest achievement in efficiency, the bewildering embodiment of an immense multitude of luxuries for which only the richest of the earth could pay. The cost of the Titanic was tremendous—it had taken many millions of dollars—many months to complete her. Besides (and best of all), she was practically unsinkable her owners said; pierce her hull anywhere, and behind was a watertight bulkhead, a sure defense to flout the floods and hold the angry ocean from its prey.

Angry is the word—for in all her triumph of perfection the Titanic was but man’s latest insolence to the sea. Every article in her was a sheer defiance to the Deep’s might and majesty. The ship is not the ocean’s bride; steel hull and mast, whirling shaft, and throbbing engine-heart (products, all, of serviceable wonderworking fire)—what kinship have these with the wild and watery waste? They are an affront and not an affinity for the cold and alien and elusive element that at all times threatens to overwhelm them.

But no one on the Titanic dreamed of danger when her prow was first set westward and her blades began the rhythmic beat that must not cease until the Atlantic had been crossed. Of all the statesmen, journalists, authors, famous financiers who were among her passengers (many of whom had arranged their affairs especially to secure passage in this splendid vessel), in all that brilliant company it may be doubted if a single mind secreted the faintest lurking premonition of a fear. Other ships could come safely and safely go, much more this monster—why, if an accident occurred and worse came to worst, she was literally too big to sink! Such was the instinctive reasoning of her passengers and crew, and such the unconsidered opinion of the world that read of her departure on the fatal day which marked the beginning of her first voyage and her last.

No doubt her very name tempted this opinion: Titanic was she titled—as though she were allied to the fabled giants of old called Titans, who waged war with the very forces of creation.

Out she bore, this giant of the ships, then, blithely to meet and buffet back the surge, the shock, of ocean’s elemental might; latest enginery devised in man’s eternal warfare against nature, product of a thousand minds, bearer of myriad hopes. And to that unconsidered opinion of the world she doubtless seemed even arrogant in her plenitude of power, like the elements she clove and rode—the sweeping winds above, the surging tide below. But this would be only in daytime, when the Titanic was beheld near land, whereon are multitudes of things beside which this biggest of the ships loomed large.

The noblest way for man to die

is when he dies for man.

Greater love hath no man.

When we imagine her alone, eclipsed by the solitude and immensity of night, a gleaming speck—no more—upon the gulf and middle of the vasty deep, while her gayer guests are dancing and the rest are moved to mirth or wrapped in slumber or lulled in security—when we think of her thus in her true relation, she seems not arrogant of power at all; only a slim and alien shape too feeble for her freight of precious souls, plowing a tiny track across the void, set about with silent forces of destruction compared to which she is as fragile as a cockle shell.

Against her had been set in motion a mass for a long time mounting, a century’s stored-up aggregation of force, greater than any man-made thing as is infinity to one. It had expanded in the patience of great solitudes. On a Greenland summit, ages ago, avalanches of ice and snow collided, welded and then moved, inches in a year, an evolution that had naught to do with time. It was the true inevitable, gouging out a valley for its course, shouldering the precipices from its path. Finally the glacier reached the open Arctic, when a mile-in-width of it broke off and floated swinging free at last.

Does Providence directly govern everything that is? And did the Power who preordained the utmost second of each planet’s journey, rouse up the mountain from its sleep of snow and send it down to drift, deliberately direct, into the exact moment in the sea of time, into the exact station in the sea of waters, where danced a gleaming speck—the tiny Titanic—to be touched and overborne?

It is easy thus to ascribe to the Infinite the direction of the spectacular phenomena of nature; our laws denote them “acts of God”; our instincts (after centuries of civilization) still see in the earthquake an especial instance of His power, and in the flood the evidence of His wrath. The floating menace of the sea and ice is in a class with these. The terror-stricken who from their ship beheld the overwhelming monster say that it was beyond all imagination vast and awful, hundreds of feet high, leagues in extent, black as it moved beneath no moon, appallingly suggestive of man’s futility amidst the immensity of creation. See how, by a mere touch—scarcely a jar—one of humanity’s proudest handiworks, the greatest vessel of all time, is cut down in her course, ripped up, dismantled and engulfed. The true Titan has overturned the toy.

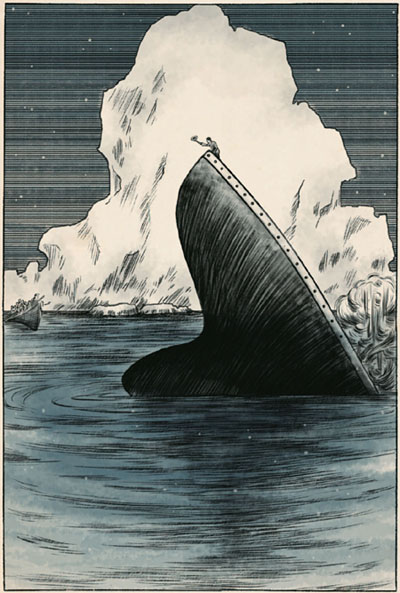

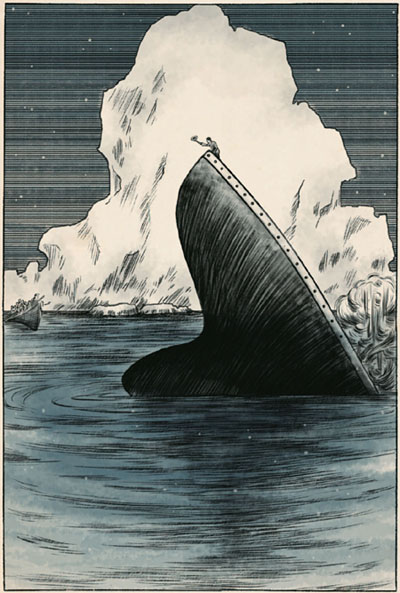

Oh, where is now the boasted strength of that great hull of steel! Pitted against the iceberg’s adamant it crumples and collapses. What of the ship unsinkable; assured so by a perfected new device? settling in the sea, shuddering to an inrush and an outburst of frigid water and exploding steam! All the effort of the thousand busy brains that built her, all the myriad hopes she bore—down, quite down! A long farewell to the toy Titan as the erasing waters fill and flatten smooth again to ocean’s cold obliterating calm the handsbreadth she once fretted and defied!

Yes, it is easy to see God only in the grander manifestations of nature; but occasionally we are stricken by His speaking in the still small voice. Hundreds on this night of wreck were thus impressed. As the great steel-strong leviathan sank into the sea, those in the fleeing lifeboats heard, amidst the thunder and the discord of the monster’s breaking-up, afar across the waters floating clear, a tremulous insistence of sweet sound, a hymn of faith—utterly triumphant o’er the solitudes! Men had left their work to perish and turned themselves to God.

When he builds and boasts of his Titanic, man may be great, but it is only when he is stripped of every cloying attribute of the world’s pomp and power that he can touch sublimity. Those on the wreck had mounted to it from the time the awful impact came. The rise began when men of intellect and noted works, of titled place and honored station, worked as true yoke-fellows with the steerage passengers to see that all the women and their little ones were safely placed within the boats. They did this calmly, while the steamer settled low and every instant brought the waters nearer to their breath; exulting as each o’erburdened lifeboat safely drew away, and cheering until the iceberg echoed back the sound. There was very little fear displayed; calm intrepidity was here the mark of a high calling. Captain Smith, indeed, was afraid, but it was only for the precious beings under God committed to his care. And how manfully he minimized at first the danger until the rising surges creeping o’er the decks betrayed the awful truth. Then was the panic time! What cries were heard! What partings had and fond farewells! What love was lavished in renunciation and in life-and-death constancy when husband and wife refused to be separated in the hour that meant the inevitable death of one. But through all the time of terror the heroes of the Titanic remained true, nor yielded hearts to fear; and then, when all was done, when the last well-laden boat had safely put away, when the chill waters could be felt encroaching in the darkness, those who voluntarily awaited death, who had exemplified the sacred words: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for a friend”—then these put heroism behind them for humility, rose to the greater height, threw themselves on Him who walked the waters to a sinking ship, as they sang in ecstasy the simple hymn of steadfast faith: “Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee”!

Thus did man assert once more his high superiority among created things—he alone has power to revert to the unseen author of them all. Though compassed about with vast unfriendly Titans of the elements, builder himself of Toy Titans, like the boasted ship, that exist at the mercy of the sea and sky—at every fresh disaster that brings to nothingness his chiefest works, his spirit yet allies itself peculiarly with the power that only may be imagined and not seen; being persuaded that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate him from the love of God.

—Fred S. Miller