COLONEL GRACIE, U.S.A., RESCUED AFTER GOING DOWN ON TITANIC’S TOPMOST DECK—HEROES ON ALL SIDES—MRS. ISIDOR STRAUS DROWNED, REFUSING TO DESERT HUSBAND—ASTOR PRAISED FOR CONDUCT

Colonel Archibald Gracie, U.S.A., the last man saved after the wreck of the Titanic, went down with the vessel, but was picked up. He was met in New York by his daughter and his son-in-law, Paul H. Fabricius.

Colonel Gracie told a remarkable story of personal hardship and denied emphatically reports that there was any panic on board the steamship after the disaster. He praised in the highest terms the behavior of both the passengers and crew and paid a high tribute to the heroism of the women passengers.

“Mrs. Isidor Straus,” said Colonel Gracie, “went to her death because she would not desert her husband. Although he pleaded with her to take her place in the boat, she steadfastly refused, and when the ship settled at the head the two were engulfed by the wave that swept the vessel.”

Colonel Gracie told how he was driven to the top-most deck when the ship settled and was the sole survivor after the wave that swept it just before its final plunge had passed.

“I jumped with the wave just as I often have jumped with the breakers at the seashore. By great good fortune I managed to grasp the brass railing on the deck above, and I hung on by might and main.

“When the ship plunged down I was forced to let go and was swirled around and around for what seemed to be an interminable time. Eventually I came to the surface to find the sea a mass of tangled wreckage.

“Luckily, I was unhurt, and, casting about, managed to seize a wooden grating floating nearby. When I had recovered my breath I discovered a canvas and cork life raft which had floated up.

“A man whose name I did not learn was struggling toward this raft from some wreckage to which he had clung. I cast off and helped him get onto the raft, and we then began the work of rescuing those who had jumped into the sea and were floundering in the water.

“When dawn broke there were thirty of us on the raft, standing knee-deep in the icy water and afraid to move lest the craft be overturned.

“Several other unfortunates, benumbed and half dead, besought us to save them, and one or two made efforts to reach us, but we had to warn them away. Had we made any effort to save them, we all might have perished.

“The hours that elapsed before we were picked up by the Carpathia were the longest and most terrible that I ever spent. Practically without any sensation of feeling because of the icy water, we were almost dropping from fatigue.

“We were afraid to turn around to learn whether we were seen by passing craft, and when some one who was facing astern passed the word that something that looked like a steamer was coming up one of them became hysterical under the strain. The rest of us, too, were nearing the breaking point.”

Colonel Gracie denied with emphasis that any men were fired upon, and declared that only once was a revolver discharged.

“This,” the colonel said, “was done for the purpose of intimidating some steerage passengers who had tumbled into a boat before it was prepared for launching. The shot was fired in the air, and when the foreigners were told that the next would be directed at them they promptly returned to the deck. There was no confusion and no panic.”

Contrary to the general expectation, there was no jarring impact when the vessel struck, according to the army officer. He was in his berth when the Titanic smashed into the submerged portion of the iceberg and was aroused by the jar.

Colonel Gracie looked at his watch, he said, and found it was just midnight. The ship sank with him at 2:22 A.M., for his watch stopped at that hour. He described these events:

“Before I retired, I had a long chat with Charles M. Hays, president of the Grand Trunk Railroad. One of the last things Mr. Hays said was this:

“‘The White Star, the Cunard and the Hamburg-American lines are devoting their attention and ingenuity to vying with one another to attain supremacy in luxurious ships and in making speed records. The time will soon come when this will be checked by some appalling disaster.’

“Poor fellow—a few hours later he was dead.

“The conduct of Colonel John Jacob Astor was deserving of the highest praise,” Colonel Gracie declared.

“The millionaire New Yorker devoted all his energies to saving his young bride, formerly Miss Force of New York, who was in delicate health.

“Colonel Astor helped us in our efforts to get Mrs. Astor in the boat. I lifted her into the boat and as she took her place Colonel Astor requested permission of the second officer to go with her for her own protection.

“‘No, sir,’ replied the officer, ‘not a man shall go on a boat until the women are all off.’

“Colonel Astor then inquired the number of the boat which was being lowered away and turned to the work of clearing the other boats and reassuring the frightened and nervous women.

“By this time the ship had begun to list frightfully to port. This became so dangerous that the second officer ordered every one to rush to starboard.

“This we did, and we found the crew trying to get a boat off in that quarter. Here I saw the last of John B. Thayer and George B. Widener of Philadelphia.”

Colonel Gracie said that despite the warnings of icebergs no slowing down of speed was ordered by the commander of the Titanic. There were other warnings, too, he said.

“In the twenty-four hours’ run ending the 14th, the ship’s run was 546 miles, and we were told that the next twenty-four hours would see even a better record posted.

“No diminution of speed was indicated in the run and the engines kept up their steady work. When Sunday evening came we all noticed the increased cold, which gave plain warning that the ship was in close proximity to icebergs or ice fields. The officers, I am credibly informed, had been advised by wireless from other ships of the presence of icebergs and dangerous floes in the vicinity. The sea was as smooth as glass and the weather clear, so that it seemed that there was no occasion for fear.

“When the vessel struck it, the passengers were so little alarmed that they joked over the matter. The few who appeared upon deck early had taken their time to dress properly and there was not the slightest indication of panic. Some fragments of ice had fallen on the deck and these were picked up and passed around by some of the facetious ones, who offered them as mementos of the occasion. On the port side, a glance over the side failed to show any evidence of damage, and the vessel seemed to be on an even keel.

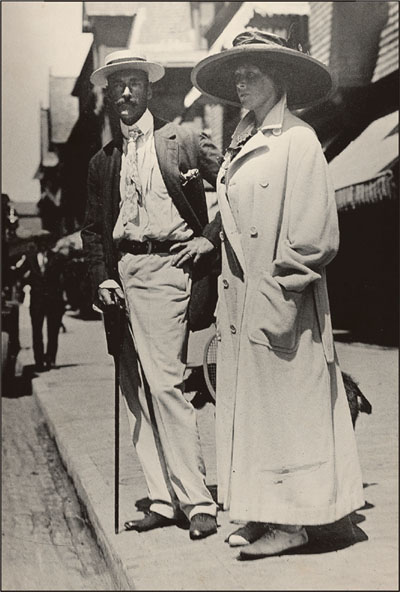

Colonel John Jacob Astor, who was lost

with the Titanic, and his wife, Madeline Force, who was rescued.

“James Clinch Smith and I, however, soon found the vessel was listing heavily. A few minutes later the officers ordered men and women to don life preservers.”

One of the last women seen by Colonel Gracie, he said, was Miss Evans, of New York, who virtually refused to be rescued, because “she had been told by a fortune teller in London that she would meet her death on the water.”

A young Englishwoman who requested that her name be omitted told a thrilling story of her experience in one of the collapsible boats, which was manned by eight of the crew from the Titanic. The boat was in command of the fifth officer, H. Lowe, whom she credited with saving the lives of many persons.

Before the lifeboat was launched Lowe passed along the port deck of the steamer, commanding the people not to jump into the boats and otherwise restraining them from swamping the craft. When the collapsible was launched Lowe succeeded in putting up a mast and a small sail.

The officer collected the other boats together, and, in case where some were short of adequate crews, directed an exchange by which each was adequately manned. He threw lines which linked the boats two by two, and all thus moved together.

Later on Lowe went back to the wreck with the crew of one of the boats and succeeded in picking up some of those who had jumped overboard, and were swimming about. On his way back to the Carpathia he passed one of the collapsible boats which was on the point of sinking with thirty passengers aboard, most of them in scant night clothing. They were rescued just in the nick of time.