DUTY AS STERN A MISTRESS AS DESPAIR GAVE MANY OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE DISPLAY OF BRAVERY—HELD PRAYER SERVICE AS SHIP SANK

The Rev. Thomas R. Byles, whose requiem mass was sung on Saturday at the hour he was to have officiated at his brother’s marriage, was last seen leading a group in prayer on the second cabin deck of the Titanic when that ship sank. On the morning of the day the boat struck the iceberg Father Byles had preached to the passengers in the steerage and most of them knew him by sight.

When the Titanic struck the priest was on the upper deck walking back and forth reading his office, the daily prayers which form part of the duties of every Roman Catholic priest. After the real danger was apparent, survivors say Father Byles went among the passengers, hearing confessions of some and giving absolution. At the last he was the center of a group on the deck where the steerage passengers had been crowded and was leading in the recitation of the rosary.

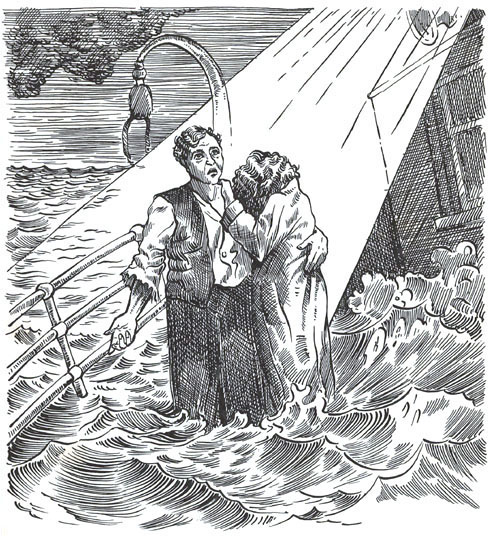

This information was given by Miss Agnes McCoy, who was taken, as soon as she landed from the Carpathia, to St. Vincent’s Hospital. She and her sister, Alice, were with their brother in the steerage. The two girls were put into a lifeboat and saw their brother swimming in the icy water. They called to him to get into their boat. He tried to grasp the side of the boat, but one of the sailors beat him back with an oar. In a minute one of the girls had reached the sailor and held his arms while the other sister pulled her brother aboard. Agnes McCoy gave this account:

“I saw Father Byles when he spoke to us in the steerage, and there was another priest with him there. He was a German and spoke in that language. I did not see Father Byles again until we were told to come up and get into the boat. He was reading out of a leather bound book [his priest’s book of hours] and did not pay any attention. He thought as the rest of us did that there wasn’t really any danger. Then I saw him put the book in his pocket and hurry around to help women into the boats. We were among the first to get away and I didn’t see him any more.

“But there was a fellow on the Carpathia who told me about Father Byles. He was an English lad who was coming over to this country with his parents and several brothers and sisters. They were all lost. He was on the deck with the steerage passengers until the boat went down. He was holding to a piece of iron, he told me, and had his hands badly cut. One of the explosions threw him out of the water and he was picked up later.

“He said that Father Byles and another priest stayed with the people after the last boat had gone and that a big crowd, a hundred maybe, knelt about him. They were Catholics, Protestants and Jewish people who were kneeling there, this fellow told me. Father Byles told them to prepare to meet God and he said the rosary. The others answered him. Father Byles and the other priest, he told me, were still standing there praying when the water came over the deck.

Nearer, my God, to thee.

“I did not see Father Byles in the water. But that is no wonder, for there were hundreds of bodies floating there after the ship went down. The night was so clear that we could see plainly and make out faces of those near us. The lights of the boat were bright almost to the last. They went out after the explosion. Then we could hear the people in the water crying for help and moaning for a long time after the boat went down.”

Postmaster General Hitchcock recommended that a provision be inserted in the pending Post Office Appropriation bill authorizing the payment of $2,000, the maximum amount prescribed by law for payment to the representatives of railway postal clerks killed while on duty, to the families of each of the three American sea post clerks who lost their lives on the Titanic.

“The bravery exhibited by these men,” Mr. Hitchcock said, “in their efforts to safeguard under such trying conditions the valuable mail entrusted to them should be a source of pride to the entire postal service, and deserves some marked expression of appreciation from the government.”

When last seen by those who survived the disaster these three clerks, John S. Marsh, William L. Gwynn and Oscar S. Woody, were on duty and engaged with the two British clerks, Iago Smith and E. D. Williamson, in transferring the 200 bags of registered mail containing 400,000 letters from the ship’s post office to the upper deck. An officer of the Titanic stated that when he last saw these men they were working in two feet of water.

Mrs. John Murray Brown, of Action, Mass., who with her sisters, Mrs. Robert C. Cornell and Mrs. E. D. Appleton, was saved, was in the last lifeboat to get safely away from the Titanic.

“The band played, marching from deck to deck, and as the ship went under I could still hear the music,” Mrs. Brown said. “The musicians were up to their knees in the water when I last saw them. My sisters and I were in different boats. We offered assistance to Captain Smith of the Titanic when the water covered the ship, but he refused to get into the boat.”

The names of the six Englishmen, a German and a Frenchman go down upon the roll of honor in the Titanic tragedy:

KRINS CLARK HUME BRAILEY TAYLOR BREICOUX WOODWARD HARTLEY

In the list of second cabin passengers on the Titanic, the names of the eight are linked under the title of “bandsmen.” When the last faint hope was gone, the eight musicians lined up on deck. Then solemnly and quietly the leader waved his baton, hands flew to instruments and over the ice laden water floated the strains of one of the most sadly beautiful hymns ever written. It was “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” To their playing, more than 1,500 souls passed from life.

Plucky Mary Downey at her switchboard played a hero’s part as well as any of the rest of those of whom the Titanic disaster made heroes. During the days of suspense following the first news of the accident to the Titanic, while there were hundreds of people at the White Star offices and while even more were calling up either by local or long distance phone, one young woman sat at the White Star switchboard and bore the worst of everything. She was there to answer the first inquiries of relatives and friends of the Titanic’s passengers, to give them what hope she honestly could, to tell of the latest developments when there were any, to meet the quick demands of the officials of the line, and lastly to give immediate service to the throng of reporters that camped about the offices. All this, and more, too, when she had an unbelievably small amount of sleep.

What was needed.

The girl’s name is Mary Downey. By the time the Carpathia had brought to port the remnants of the Titanic’s crew and passengers Miss Downey was as much of a hero among the White Star people as any one could be. A good many who were in a position to know have had much to say about her sticking to the job day and night. She was about the most composed person in the offices during those troubled times. Even Mr. Franklin, the general manager, took time once to remark to several reporters that Miss Downey “was a wonder.”

The news of the disaster reached New York early on Monday morning; Miss Downey reached her place at 6 o’clock. She was there almost continuously until 8 o’clock on Tuesday morning. Part of the time she had an assistant. That afternoon after a few hours’ rest, but without having gone to her home, she returned and again took up the answering of the endless inquires. The greater proportion of them she referred to clerks, but every one had to be looked into first by her. And when the clerks were all occupied she herself met the brunt of whatever words of sadness or criticism came over the wire.

Miss Downey had no idea how many phone calls she answered or made, but she knows that there are eleven trunk lines coming into the White Star offices, and that it was only during the hours of the night that these were not all in use.

The newspaper men who stayed around day and night appreciated as much, if not more, than any one else the service which Miss Downey rendered. For instance, when Mr. Franklin announced that the Titanic had sunk there were nearly a dozen reporters who rushed to office phones. Within a minute each had his own office on the wire and was flashing the news.