SPEED OF SHIP NOT LESSENED ON WARNING—WITNESSES ALSO SHOWED LACK OF SMALL BOATS COST MANY LIVES—ISMAY DESCRIBED WRECK—DENIED HE FLED BEFORE WOMEN HAD CHANCE TO LEAVE THE VESSEL—DESCRIBED RESCUE EFFORTS

The seriousness of the inquiry by the United States Senate investigating committee into the Titanic disaster was disclosed when Senator William Alden Smith of Michigan, the chairman, at first flatly refused to let any of the officers or the two hundred-odd members of the crew of the sunken steamship get beyond the jurisdiction of the United States government. The men were all to have sailed back home on the steamer Lapland.

Later it was decided that the greater part of the crew would be permitted to sail, but that the twelve men and four officers among the survivors under subpoena, together with J. Bruce Ismay, would not be allowed to depart.

It was explained that Mr. Ismay was anxious to leave at once for Europe, as he had been worn out by his experiences, and felt the need of returning quickly to his English home for a rest. His pleas, however, were unavailing.

The first day brought out important features in connection with the wreck. These were disclosed in the examination of Mr. Ismay, Arthur Henry Rostron, captain of the rescue ship Carpathia, and Second Officer Lightoller of the Titanic, William Marconi, inventor of the wireless telegraph; Thomas Cottam, the wireless operator of the Carpathia, and others.

Among other things, the first day’s testimony showed: That the biggest ship ever built sank in midocean because it was being rushed forward almost at top speed and crashed into a field of icebergs after warnings had been given to look out. That the small number of lives saved was due to the fact there were not enough lifeboats on board to accommodate the passengers.

Because of his position as managing director of the White Star Line, the testimony of Mr. Ismay was the most important given.

Mr. Ismay, who plainly showed his nervousness while on the stand, told in whispers of his escape from the sinking liner from the time he pushed away in a boat with the women until he found himself, clad in his pajamas, aboard the Carpathia.

He was not sure in just what boat he left the Titanic, nor was he sure how long he remained on the liner after it struck. He added, however, that before he entered a lifeboat he had been told that there were no more women on the deck.

Mr. Ismay denied that there had been any censoring of messages from the Carpathia. Other witnesses bore him out in this, with the explanation that the lone wireless operator on the rescue ship was unable to send matter for the press.

Mr. Ismay, in response to Senator Smith’s questionings, gave an account of his experiences.

“As near as I remember, it was the 1st of April that the Titanic made its trial trip, which was perfectly satisfactory. On the voyage over, we left Southampton at 12 o’clock and arrived at Cherbourg that evening, having made the run at sixty-eight revolutions. We left Cherbourg and proceeded to Queenstown, arriving there, I think, at midday on Thursday. We ranged, I think, about seventy revolutions. We embarked passengers and proceeded at seventy revolutions. I am not absolutely clear on the run on the first day. I think it was between 464 and 474 miles. The second day we proceeded at seventy-two revolutions, the third day at seventy-five. I think that day we ran either 576 or 579 miles. The weather continued fine, except for about ten minutes of fog one evening. The accident took place on Sunday night. The exact time I don’t know. I was in bed asleep when it happened. The ship sank, I am told, at 2:20 in the morning. The ship had never been at full speed. That would have been seventy-eight revolutions, working up to eighty. It hadn’t all its boilers on. I may say that it was intended, if we had fair weather Monday afternoon or Tuesday, to drive the steamship at full speed. Unfortunately the catastrophe prevented this.

“I presume the impact awakened me. I lay for a minute or two and then I got up and went into the passageway, where I met a steward and asked him what was the matter. He replied, ‘I don’t know, sir.’ Then I went back to my stateroom, put on my overcoat and went up to the bridge, where I saw Captain Smith. ‘What has happened?’ I asked him. ‘We have struck ice,’ he replied. I asked if the injury was serious, and he said he thought so. Then I came down and in an entryway saw the chief engineer. I asked him if he thought there was any serious injury. He said he believed there was. Walking along the deck I met an officer on the starboard side and assisted him as best I could in getting out the women and children. I stayed up on deck until the starboard collapsible boat was lowered.”

Mr. Ismay stated that an official representative of the builders, Mr. Thomas Andrews, was on board to see that everything was satisfactory and wherein improvements might be made, but he was lost.

“Did you or the captain ever consult about movement of the ship?”

“Never.”

“Was it supposed that you could reach New York by 5 o’clock Wednesday morning without putting the steamship to its full capacity?”

“Oh, yes. Nothing was to be gained by arriving sooner than that.”

Mr. Ismay testified that the revolutions were being gradually increased, as was customary with a new ship. The speed on Saturday was 75 revolutions, but that was nothing to full speed. Mr. Ismay did not know ice had been reported, and had never seen an iceberg. He expected that some time Sunday night they would come into the ice region.

“Did you have any consultation with the captain regarding this matter?”

“Absolutely none. It was entirely out of my province. I was simply a passenger aboard the ship.”

“On which decks were the boats?”

“The lifeboats were all on one deck—the sun deck.”

They were filled, a crew put in, and they were sent away. There were four men aboard the boat on which Mr. Ismay escaped.

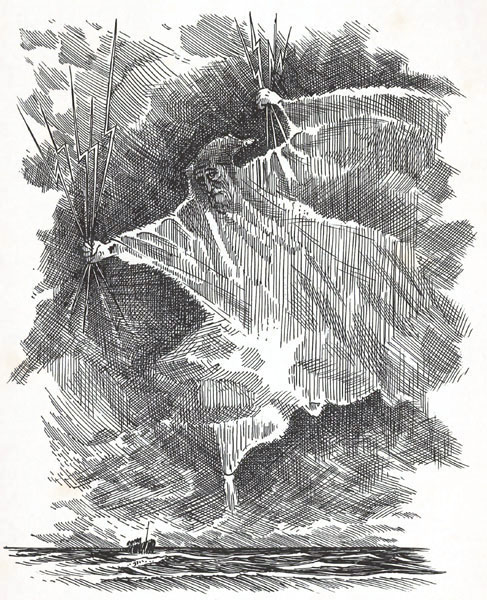

J. Bruce Ismay, one of the Titanic survivors, testifies at the U.S. Senate inquiry into the disaster.

Mr. Ismay could not say that all the women and children had been taken off. In his boat there were about forty-five people. Three other boats he saw were loaded about the same. There was no struggle by men to get into the boats and the women were taken just as they came. Mr. Ismay said he was on the Titanic practically until it sank, perhaps an hour and a quarter.

“What were the circumstances of your departure from the ship?” asked Senator Smith.

“I was immediately opposite the lifeboat. A certain number of people were in it. An officer called to know if there were any more women. There were no women in sight on the deck then. There were no passengers about and I got in.”

Nearly all the passengers Mr. Ismay saw had on life preservers. He did not see anyone jump into the sea. They steered their lifeboats toward a distant light and spent about four hours in the open sea.

“How many lifeboats were there?”

“Twenty altogether, I think; sixteen of them wooden lifeboats, but I am not absolutely certain.”

Mr. Ismay said the sea was very calm.

“What can you say about the sinking and disappearance of the ship?” asked Senator Smith.

“Nothing; I did not see it go down.”

“I was sitting with my back to the ship; I did not wish to see it go. I was pushing with an oar. I am glad I did not see it.”

Mr. Ismay said the Titanic conformed to the British Board of Trade’s requirements, else it could not have sailed. The lifeboats were the Titanic’s own and not borrowed from any other ship of the White Star line. Mr. Ismay had nothing to do with the selection of the men in his own lifeboat; they were designated by Mr. Wild, the chief officer.

Senator Smith wished to know how much water the ship could hold without sinking.

“The ship was especially constructed so as to float with any two compartments—any two of the biggest compartments—full of water, and I think I am right in saying there are few ships today of which the same can be said. When we built the ship we had this in mind. If the ship had hit the ice head-on, in all human probability that ship would have been afloat today, but the information I received is that it struck a glancing blow between the end of the forecastle and the captain’s bridge.”

Mr. Ismay feared all the women and children were not saved. He could say nothing of equipment and so on, except that the Board of Trade rules had been complied with and that all data and information was at the committee’s disposal. He had made no attempt to interfere with the wireless service in any way.

Captain Rostron of the Carpathia followed Mr. Ismay. He told Mr. Smith that he had been captain of the Carpathia since last January, but that he had been a seaman twenty-seven years.

“What day did you last sail from New York with the Carpathia?” asked Senator Smith.

“April 11,” said Captain Rostron, “bound for Gibraltar.”

“How many passengers did you have?”

“I think 120 first-class, 50 second-class, and about 565 third-class passengers.”

Wireless anarchy.

“Tell the committee all that happened after you left New York.”

“We backed out of the dock at noon, Thursday. Up to Sunday midnight we had fine, clear weather. At 12:35 Monday morning I was informed of the urgent distress signal from the Titanic.”

“By whom?”

“The wireless operator and first officer. The message was that the Titanic was in immediate danger. I gave the order to turn the ship around. I set a course to pick up the Titanic, which was fifty-eight miles west of my position. I sent for the chief engineer; told him to put on another watch of stokers and make all speed for the Titanic. I told the first officer to stop all deck work, get out the lifeboats, and be ready for any emergency. The chief steward and doctors of the Carpathia I called to my office and instructed as to their duties. They were instructed to be ready with all supplies necessary for any emergency.”

Arriving on the scene of the accident, Captain Rostron testified, he saw an iceberg straight ahead of him, and, stopping at 4 A.M., he picked up the first lifeboat.

“By the time I got the boat aboard day was breaking,” said the captain. “In a radius of four miles I saw all the other lifeboats. On all sides of us were icebergs; some twenty were 150 to 200 feet high, and numerous small icebergs, or ‘growlers.’ Wreckage was strewn about us. At 8:30 all the Titanic’s survivors were aboard.”

Then, with tears filling his eyes, Captain Rostron said he called the purser.

“I told him,” said Captain Rostron, “I wanted to hold a service of prayer—thanksgiving for the living and a funeral service for the dead. I went to Mr. Ismay. He told me to take full charge. An Episcopal clergyman was found among the passengers and he conducted the services.”

Three members of the Titanic’s crewwere taken from the lifeboats, dead from exposure. They were buried at sea.

Asked about the lifeboats, Captain Rostron said he found one among the wreckage in the sea. The lifeboats on the Titanic, Captain Rostron said, were all new and in accordance with the British regulations.

“Was the Titanic on the right course when it first spoke to you?” Senator Smith asked.

“Absolutely on its regular course bound for New York,” said the captain. “It was in what we call the southerly to avoid icebergs.”

Captain Rostron declined to say if Captain Smith had warning enough and might have avoided the ice if he had heeded.

“Would you regard the course taken by the Titanic in this trial trip as appropriate, safe and wise at this time of the year?” Senator Smith asked.

“Quite so.”

“What would be safe, reasonable speed for a ship of that size and in that course?”

“I didn’t know the ship,” the captain said, “and therefore cannot tell. I had seen no ice before the Titanic signaled us, but I knew from its message that there was ice to be encountered. But the Carpathia went full speed ahead. I had extra officers on watch and some others volunteered to watch ahead throughout the trip.”

Captain Rostron said the Carpathia had twenty lifeboats of its own, in accordance with the British regulations.

“Wouldn’t that indicate that the regulations are out of date, your ship being much smaller than the Titanic, which also carried twenty lifeboats?” Senator Smith asked.

“No. The Titanic was supposed to be a lifeboat itself.”

“You say that the captain of a ship has absolute control over the movements of his vessel?”

“Yes, by law that is the rule,” Captain Rostron answered. “But suppose we get orders from the owners of our ship to do a certain thing. If we do not execute that order we are liable to dismissal. When I turned back for New York with the rescued I sent a message to the Cunard line office stating that I was proceeding to New York unless otherwise ordered. I then immediately proceeded. I received no order to change my course.”

Senator Smith said some complaint had been heard that the Carpathia had not answered President Taft’s inquiry for Major Butt. Captain Rostron declared a reply was sent “not on board.”

Absolutely no censorship was exercised, he said. The wireless continued working all the way in, the Marconi operator being constantly at the key. In discussing the strength of the Carpathia’s wireless, Captain Rostron said the Carpathia was only fifty-eight miles from the Titanic when the call for help came.

“Our wireless operator was not on duty,” said Captain Rostron, “but as he was undressing he had his apparatus to his ear. Ten minutes later he would have been in bed and we never would have heard.”

William Marconi, the wireless inventor, took the stand as soon as the hearing was resumed. He said he was the chairman of the British Marconi Company. Under instructions of the company, he said, operators must take their orders from the captain of the ship on which they are employed.

“Do the regulations prescribe whether one or two operators should be aboard the ocean vessel?”

“Yes, on ships like the Titanic and Olympic, two are carried,” said Mr. Marconi. “The Carpathia, a smaller boat, carries one. The Carpathia wireless apparatus is a short distance equipment. The maximum efficiency of the Carpathia wireless, I should say, was 200 miles. The wireless equipment on the Titanic was available 500 miles during the daytime and 1,000 miles at night.”

“Do you consider that the Titanic was equipped with the latest improved wireless apparatus?”

“Yes; I should say that it had the best.”

Senator Smith asked if amateur or rival concerns interfered with the wireless communication of the Carpathia.

“I am unable to say. Near New York I have an impression there was some slight interference, but when the Carpathia was farther out in touch with New York and Nova Scotia there was practically no interference.”

“Did you hear the captain of the Carpathia say in his testimony that they caught this distress message from the Titanic almost providentially?” asked Senator Smith.

“Yes, I did. It was absolutely providential.”

“Ought it not be incumbent upon ships to have an operator always at the key?”

“Yes, but the ship owners do not like to carry two operators when they can get along with one. The smaller boat owners do not like the expense of two operators.”

Charles Herbert Lightoller, second officer of the Titanic, said he understood the maximum speed of the Titanic, as shown by its trial tests, to have been 22½ to 23 knots.

Senator Smith asked if the rule requiring life-saving apparatus to be in each room for each passenger was complied with.

“Everything was complete,” said Lightoller. During the tests, he said, Captain Clark of the British Board of Trade was aboard the Titanic to inspect its life-saving equipment.

“How thorough are these captains of the Board of Trade in inspecting ships?” asks Senator Smith.

“Captain Clark is so thorough that we called him a nuisance.”

Lightoller said he was in the sea with a life belt on one hour and a half after the Titanic sank. When it sank he was in the officers’ quarters and all but one of the lifeboats were gone. This one was caught in the tackle and they were trying to free it.

Lightoller said that on Sunday he saw a message from “some ship” about an iceberg ahead. He did not know the Amerika sent the message, he testified.

The ship was making about 21 to 2½ knots, the weather was clear and fair, and no anxiety about ice was felt, so no extra lookouts were put on.

“When Capt. Smith came on the bridge at five minutes of 9, what was said?”

“We talked together generally for twenty or twenty-five minutes about when we might expect to get to the ice fields. He left the bridge, I think, about twenty-five minutes after 9 o’clock, and during our talk her told me to keep the ship on its course, but that if I was the slightest degree doubtful as conditions developed to let him know at once.”

“What time did you leave the bridge?”

“I turned over the watch to First Officer Murdock at 10 o’clock. We talked about the ice that we had heard was afloat, and I remember we agreed we should reach the reported longitude of the ice floes about 11 o’clock, an hour later. At the time the weather was calm and clear. I remember we talked about the distance we could see. We could see stars in the horizon. It was very clear.”

Lightoller testified that the Titanic’s decks were absolutely intact when it went down. The last order he heard the captain give was to lower the boats.

The last boat, a flat collapsible, to put off was the one on top the officers’ quarters. Me jumped upon it on deck and waited for the water to float it off. Once at sea it upset. The forward funnel fell into the water, just missing the raft, and overturning it. The funnel probably killed persons in the water.

“This was the boat I eventually got on. No one was on it when I reached it. Later about thirty men clambered out of the water on to it. All had on life preservers.”

“Did any passengers get on?” asked Senator Smith.

“J. B. Thayer, Colonel Gracie and the second Marconi operator were among them. All the rest taken out of the water were firemen. Two of these died that night and slipped off into the water. I think the senior Marconi operator was one of the three. We took on board all we could and there were no others in the water near at hand.”

When Lightoller left he saw no women or children on board, though there were a number of passengers on the boat deck. The passengers were selected to fill the boat by sex, Lightoller himself putting on all the women he saw, except the stewardesses. He saw some women refuse to go.

In the first boat to be put off Lightoller said he put twenty to twenty-five. Two seamen were placed in it. The officer said he could spare no more, and that the fact that women rowed did not show the boat was not fully equipped.

At that time he did not believe the danger was great. Two seamen placed in the boat, he said, were selected by him, but he could not recall who they were. He said he named them because they were standing near. The second boat carried thirty passengers, with two men.

“By the time I came to the third boat I began to realize that the situation was serious, and I began to take chances. I filled it up as full as I dared, sir—about thirty-five, I think.”

In loading the fourth lifeboat, Lightoller said he was running short of seamen.

“I put two seamen in and one jumped out. That was the first boat I had to put a man passenger in. He was standing nearby and said he would go if I needed him.

“I said, ‘Are you a sailor?’ and he replied that he was a yachtsman. Then I told him that if he was sailor enough to get out over the bulwarks to the lifeboat, to go ahead. He did, and proved himself afterward to be a brave man. I didn’t know him then, but afterward I looked him up. He was Major Peuchen of Toronto.”

On the fifth boat Lightoller had no particular recollection.

“The last boat I put out, my sixth boat,” he said, “we had difficulty finding women. I called for women and none were on deck. The men began to get in—and then women appeared. As rapidly as they did, the men passengers got out of the boat again.”

“The boat’s deck was only ten feet from the water when I lowered the sixth boat. When we lowered the first the distance to the water was seventy feet.”

All told, Lightoller testified, 210 members of the crew were saved.

“If the same course was pursued on the starboard side as you pursued on the port filling boats, how do you account for so many members of the crew being saved?” asked Chairman Smith.

“I have inquired especially and have found that for every six persons picked up five were either firemen or stewards.”

Some lifeboats, the witness said, went back after the Titanic sank and picked up men from the sea.

Lightoller said he stood on top of the officers’ quarters and as the ship dived he faced forward and dived also.

“I was sucked against a blower and held there. A terrific gust came up the blower—the boilers must have exploded—and I was blown clear—barely clear. I was sucked down again, this time on the ‘Fidley’ grating.”

Colonel Gracie’s experience was similar. Lightoller did not know how he got loose, perhaps another explosion. He came up by a boat, on which he clambered.

Thomas Cottam, aged twenty-one, of Liverpool, the Marconi operator on the Carpathia, was the next witness.

He said he had no regular hours for labor on the Carpathia. Previous witnesses had testified he was not “on duty” when he received the Titanic’s signal for help. He was uncertain whether he was required to work at night. He had not closed his station for the night, which is accomplished by switching the storage battery out. He was listening for a confirmation message from the Parisian, while he was preparing to retire, and caught the Titanic’s distress signal by chance.

“When you got the distress message from the Titanic Sunday night, how did you get it?”

“I called the Titanic myself, sir.”

“Who told you to call the Titanic?”

“No one, sir; I did it of my own free will.”

“What was the answer?”

“‘Come at once,’ was the message, sir.”

“I was in communication with the Titanic at regular intervals until the final message,” said Cottam. “This was ‘Come quick; our engine room is filling up to the boilers.’”

Cottam said that after the Titanic’s survivors were picked up he worked practically continuously until Tuesday, when he fell asleep at his post. He could not tell when he dropped from exhaustion nor when he awoke.