MEMBERS OF THE CREW TOLD THEIR STORIES OFFICIALLY, DESCRIBING FOR THE MOST PART THE LOADING OF THE LIFEBOATS AND THE CONDUCT OF ISMAY

Harold G. Lowe, fifth officer of the Titanic, told his story of the wreck before the investigation committee. His testimony revealed the fact that, with a volunteer crew, he rescued four men from the water, saved a sinking collapsible lifeboat by towing it and took off twenty men and one woman from the bottom of an overturned boat, all of whom he landed safely on the Carpathia. Lowe testified that he looked over the lifeboats in Belfast Harbor and found everything in them, except a dipper which was missing from one. He was not sure whether a fire drill had been held or not. He did not know whether the officers were at their right places on the side of the ship where he was or not. He was not on duty Sunday night and could not be induced to make a positive statement of the ship’s position, though he had a memorandum of the speed on that day as a fraction below 21 knots an hour. He asserted that he was a temperate man.

The witness said he did not know when he was awakened. He said he dressed hurriedly and went on deck and found people with life belts on the boats being prepared. He began working at the lifeboats.

“I was working the boats under First Officer Murdock,” he said. “Boat No. 5 was the first one lowered.

“There were about ten officers helping, two at each end, two in the boat, and others at the ropes.”

“A steward met me on the Carpathia. He said to me, ‘What did you say to Ismay that night on the deck?’ I said that I did not know that I had said anything to Mr. Ismay. I did not know him. Well, the steward on the Carpathia said I had used strong language to Mr. Ismay. I happened to talk to Ismay because he appeared to be getting excited. He was saying excitedly, ‘Lower away, lower away, lower away.’”

Chairman Smith asked Mr. Ismay about the language and Mr. Ismay suggested that the objectionable language be written down to see if it was appropriate. This was done. They returned to the question of lifeboats after Lowe explained that Ismay “was interfering with our work. He was interfering with me, and I wanted him to get back so that we could work. He was trying to get in the boat.”

“How many men were in the boat?”

“I’m not sure, sir, but I should say about ten.”

Lowe denied having conversed with Mrs. Douglas or Mrs. Ryerson on board the Carpathia.

Senator Smith asked Lowe if in his opinion the lifeboat before it was lowered was loaded to its proper capacity.

Lowe tried to avoid making a direct answer. Senator Smith insisted upon an answer.

“Yes, sir,” said Lowe, finally, “I think it was properly loaded for lowering.”

“What is the official quota for such a lifeboat?”

“It can carry sixty-five adults and say, a boy or girl.”

“Then you wish the committee to understand that a lifeboat under British regulations could not be lowered with safety with new tackle and equipment containing more than fifty people?”

“The dangers are if you overcrowd the boat it will buckle up from the two ends,” said Lowe. “The 65.5 is a floating capacity. If you load from the deck to lower I should not like to put more than fifty in a lifeboat.”

Senator Smith referred to Third Officer Pitman’s testimony in which he said there were thirty-five persons in lifeboat No. 5. That being the case, he asked why Pitman could not have gone to the rescue of the drowning, whose cries he heard plainly, but did not heed.

“Had he attempted to rescue those in the water he would have endangered the lives of those with him,” Lowe asserted.

Senator Smith asked if it were not true that the reason why the boats were not properly loaded was because the crew were not able to row. The witness denied this.

“What was the drill for at Southampton?” asked the chairman.

“It was for the board of trade.”

“There were eight men to a boat then. They were all oarsman. Where were they when you were loading lifeboat No. 5?

“You must remember, sir, we were in harbor and we had the pick of the men. At the time of the collision the men went down with the ‘bosun’ to clear away the gangway doors to make way for the loading.”

The witness said the discipline was excellent. Only one boat, a collapsible one, overturned.

Senator Smith asked the number of the crew and the witness said so far as he knew there were 903 of them.

“And with 903 men aboard,” said the senator, “you did not have enough to man twenty lifeboats properly?”

The witness demurred and the chairman showed his disapproval, going to the extent of criticizing the officer’s refusal to make direct replies.

Senator Smith then sought to discover whether any men, women, or children had been refused admission to the boats or were put out of the boats after they had gotten in. The officer said no one was refused and declared the only confusion was by the passengers interfering with the lowering gear.

“There was no such thing as selecting. First we took the women and children, then others as they came. There was a procession at both ends of the boat; in little knots they were, little crowds.”

“Was Mr. Ismay there?”

“Yes, he was; he was right alongside of me. I didn’t know it was Mr. Ismay then, but I know now. It was the same man whom I had ordered not to interfere in lowering No. 5. But he took hold and was helping afterward. I could see his face in the glare of the rockets, and he aided in lowering boat No. 3.”

Lowe told of tying five of the lifeboats together, transferring the passengers from his boat, and then called for volunteers to row back to the wreck.

“We rowed back and around the wreck,” said the witness, “and we picked up four men who were struggling in the water.”

“You said a moment ago that you had waited before returning to the wreck until ‘things quieted down,’” said Senator Smith. “What did you mean by ‘quieted down?’”

“Until the cries ceased.”

“The cries of the drowning?”

“Yes, sir. We did not dare go into the struggling mass. It would have sunk us. We remained on the edge of the scene, but it would have been suicide to have gone in.”

“How long did it require for things to get quiet?”

“About an hour and a half.”

“How many persons were on your boat when you went alongside the Carpathia?”

“About forty-five. I took them off a sinking collapsible boat. I left the bodies of three men.”

Senator Smith wanted to know about the shooting on board the Titanic while it was sinking. Lowe said he had fired three shots into the water to scare away some immigrants on one of the decks who he feared were about to swamp a loaded boat by jumping. He was certain the shots struck no one.

Chief interest in the testimony of C. H. Lightoller, second officer of the Titanic, was centered in his story of the actions of J. Bruce Ismay.

Senator Burton asked the witness to relate his conversation with Ismay on the Carpathia. Lightoller said he and his brother officers talked over the sailing of the Cedric and had agreed it would have been a “jolly good idea” if they could catch the vessel. It would result in keeping the men together and let everyone get home.

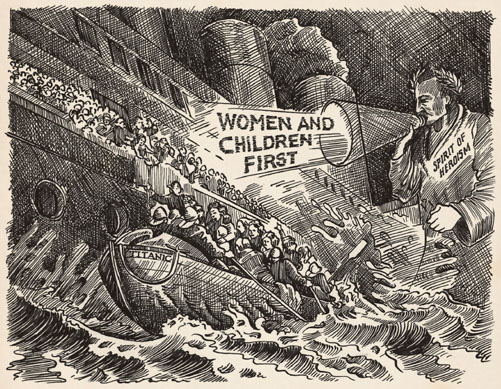

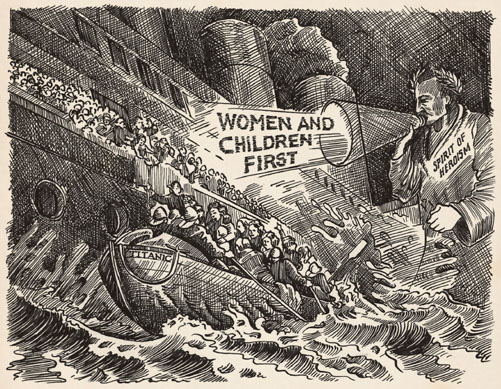

The spirit of heroism.

“Mr. Ismay, when the weather thickened, remarked to me,” said Lightoller, “that it was hardly possible that we could catch the boat. He asked me if I thought it desirable that he send a wireless to hold the Cedric. We were all agreed that it was the best course and we all advised it.”

“I would say that at that time Mr. Ismay was in no mental condition to transact business,” said Lightoller. “He seemed to be possessed with the idea that he ought to have gone down with the ship because there were women who went down. I tried my best to get that idea out of his mind, but could not. I told him that there was more for him to do on earth and that he should not let the idea possess him that he had done a wrong in not staying back to drown. The doctor on the Carpathia had trouble with Mr. Ismay on the same ground.

“I was told on the Carpathia that Chief Officer Wild, who was working at the forward collapsible boat, told Mr. Ismay there were no more women to go. Ismay still stood back and Wild, who was a big, powerful man, bundled him into the collapsible boat.”

Senator Smith asked Lightoller why when he testified in New York he did not tell about the sending of the telegram from the Carpathia urging that the Cedric be held.

“I did not say anything about it then because there had been nothing said about the telegram at that time,” said Lightoller.

“Did you know when you sent the message the Senate was going to hold an investigation?”

“Most certainly not, or the telegram would never have been sent. Our sole idea was to keep witnesses together for just such an investigation, which we knew would be made in England.”

Lightoller said that S. Hemmings, a lampman, who was waiting to testify before the committee, walked the length of the ship just before it sank and had seen only two women.