![]()

![]()

![]()

Fighting Colors, Insignia, and Markings

![]()

In aviation studies, it seems that almost more effort and ink are expended in reconstructing how particular aircraft must have looked than in describing what they did in battle. Such research can be elusive and frustrating. Aircraft paint jobs were often temporary and quite arbitrary. Even locating the original directives and technical orders cannot be decisive, for units varied in their rendition of orders regarding markings. For the U.S. Navy in the period Pearl Harbor through Midway, the problem is compounded by a paucity of documents and photographs due to the loss of several carriers. The following is offered only as an outline and general discussion, but even that can be useful. The aircraft were painted the way they were for specific reasons, and it is hoped this aspect will be brought out here.

The color schemes, insignia, and markings of U.S. naval aircraft were in general controlled by the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) and the relevant type commands—for the carrier squadrons, by Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force (ComAirBatFor). The directives in effect in early December 1941 generally followed two BuAer letters: 26 February 1941 and 13 October 1941. The first signaled the end of the Navy’s highly colorful squadron markings: tail, fuselage bands, wing chevrons, and cowl colors. It decreed placement of the national insignia on both sides of the fuselage, but removed them from the upper right and lower left wing panels. The second letter (13 October 1941) directed that all fleet aircraft be painted nonspecularly, with all upper surfaces a blue-gray and lower surfaces a light gray, the line of demarcation to be “feathered” or blended indistinctly, so as not to have a clear line of demarcation. This pattern of colors remained in effect after the outbreak of the war and characterized naval aircraft throughout the period under discussion here.1

The national insignia was by definition a solid red circle inside a white, five-pointed star, which in turn was inside a blue, circumscribed circle. Prewar painting regulations prescribed the locations of the national insignia as shown in the table.

Aircraft markings involved a number of different sets of letters and numerals to indicate model numbers, service, and aircraft identification. On the tail of each aircraft were letters and digits (by regulation one inch high and one inch wide, with ¼-inch stroke). They revealed the model designation (F4F-3, F4F-3A, or F2A-3), which was placed on the rudder; the bureau number (or individual aircraft acceptance serial number), which was painted on the vertical fin even with the model designation; and finally the service identification. This last one for the carrier fighters consisted of the word NAVY placed just above the bureau number on the vertical fin. By regulation, the color of these tail markings was to be black, but often they were white.

Included in the category of aircraft markings were the individual squadron designations and plane markings. They consisted of block letters, twelve inches high, located on the fuselage forward of the fuselage stars. First came the squadron number, then the class of squadron (on carriers: F for fighting, B for bombing, S for scouting, and T for torpedo), and finally the individual plane number within the squadron. Thus 6-F-4 would mean the number four aircraft in Fighting Squadron Six.

Variation existed in the fighting squadrons as to the color of the squadron designations and the placement of additional plane numbers on their aircraft. Fighting Squadrons Two and Three used white letters and numerals for their fuselage designations. They also painted small white numerals giving the plane number on both sides of the engine cowling and on each upper wing panel as well. Both squadrons also used white bureau numbers, model designations, and service identifications on the tails of their aircraft. The Enterprise’s VF-6 before the start of the war likewise utilized white letters and numerals for all markings, but the trend in that carrier air group was shifting toward black, and at least two of the four squadrons had changed to black, for fuselage markings at least. The color of aircraft markings may have had some relation to which division the carrier was in. Carrier Division One comprised the Lexington and the Saratoga, while Carrier Division Two consisted only of the Enterprise in the absence of the Yorktown in the Atlantic.

The outbreak of war on 7 December 1941 saw a number of unfortunate incidents involving misidentification and shooting at friendly aircraft. The worst involved VF-6 the evening of the Pearl Harbor attack, when four of six F4Fs were shot down by American antiaircraft gunners. Consequently, on 21 December on Oahu, representatives of the Army’s Hawaiian Department and the Navy’s Patrol Wing Two conferred on how to improve and standardize aircraft insignia and markings. They decided first of all to restore the national insignia to both the left and right upper and lower wing panels, and to increase the diameters of the circles to equal the full chord of the wings. They recommended the national insignia be restored to the fuselage wherever it was not so located (for most aircraft, the national insignia would be placed on the rear fuselage), and that the circles be increased to the maximum practical diameter. In accordance with Army Air Corps practice, the conference recommended that the Navy adopt the painting of rudders with seven red and six white horizontal stripes alternately spaced and of equal size.2

A day or two after the meeting, the aviation officer on the Pacific Fleet staff wrote up a despatch, sent out by CinCPac, that reported the findings of the conference but added a few changes. The CinCPac message agreed with the use of national insignia on all four wing panels, but specified they should not overflow onto the ailerons; that is, they were not as big as the conference recommended. The fuselage circles, according to CinCPac, should be twenty-four inches in diameter, which for most aircraft certainly was not the largest practical diameter. As for the rudder stripes, CinCPac decreed they should be painted with alternate red and white stripes about six inches wide, with red stripes on top and bottom. This meant an odd number of stripes, but not necessarily thirteen!

Without reference to the CinCPac despatch, Cdr. John B. Lyon (AirBatFor structures officer at Pearl) issued on 23 December a comprehensive directive for the carrier squadrons to change insignia and markings.3 It followed closely the findings of the 21 December conference. Maximum-sized national insignia circles were to be placed on upper and lower wing panels, with the center of the star approximately one-third of the distance from the wingtip to the fuselage. As translated into measurements (by NAS Pearl Harbor) for the fighters, it meant for the F4F-3s and -3As wing circles seventy-three inches in diameter and centered sixty-six inches from the wingtip. For the F2A-3s, the wing circles became sixty-eight inches in diameter and sixty-one inches from the wingtip. In both instances the wing stars overflowed onto the ailerons.

With regard to fuselage stars, Lyon’s orders called for them to be increased to the maximum diameter as well. For the fighters this became:

(a) F4F-3,-3As: circles fifty-eight inches in diameter centered thirty inches aft of the trailing edge of the wing

(b) F2A-3s: circles forty-three inches in diameter centered nineteen inches aft of a line with rear hatch cover

This entailed moving squadron designations behind the fuselage circles. As for striped tails, the AirBatFor directive specified seven red and six white stripes evenly spaced between the top and bottom of the rudder. Width of stripes depended on the size of the rudder. For the fighters, this translated to:

(a) F4F-3,-3A: rudder height 67½ inches = 5.2-inch stripes

(b) F2A-3: rudder height 54½ inches = 4.2-inch stripes

The painting orders kept the squadrons busy, and implementation of the scheme took mainly until mid- and late January to complete for those who were doing it. The Lexington’s VF-2 and the Enterprise’s VF-6 seem to have been the only fighting squadrons to comply with the AirBatFor letter. Paul Ramsey reported on 30 January that his squadron had been repainted, but that was just before he turned over the F2As to the marines. Fighting Six appears to have been the only squadron to take the scheme into combat. Its F4Fs sported the huge wing and fuselage circles. They retained white cowl numerals, but the fuselage code was changed to black, F-(plane number) without the squadron number before it. Jimmy Thach’s Fighting Three seems not to have repainted its aircraft at all, except to add thirteen tail stripes. There was much swapping of aircraft between squadrons; so one unit very rarely presented a unified appearance.

In Washington, the authorities at BuAer took steps to comply with the CinCPac recommendation and followed it to the letter except for the rudder stripes. On 5 January 1942, the bureau issued a Navy-wide directive. With regard to the wing insignia, it called for circles on all four wing panels to be the maximum diameter without overflowing onto the aileron.4 The fuselage circles were to be twenty-four inches in diameter, and the rudders striped with thirteen alternating stripes (seven red and six white). Squadrons were to effect these changes as soon as possible. This was a big difference from the orders of AirBatFor on 23 December! The 5 January BuAer letter reached Pearl Harbor in mid-February, and Rear Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch forwarded it on 21 February to the fleet. He added: “The retention of the present markings is satisfactory until the next scheduled repainting where there is no fundamental difference between these and those called for above.”5 The days of VF-6’s huge wing and fuselage circles were numbered.

Grumman F4F-3A Wildcat, Bureau Number 3916, 6-F-5 (Fighting Six) as flown on 7 December 1941 by Ens. James G. Daniels III, USN. This aircraft displays the Navy’s carrier plane markings and insignia in force at the outbreak of the Pacific War. The evening of 7 December, Jim Daniels was very nearly shot down by American antiaircraft fire over Pearl Harbor which did claim five other VF-6 F4Fs. BuNo. 3916 flew with VF-6 from 26 May 1941 until 17 March 1942 and saw combat in the Enterprise’s early raids. Thereafter it was used by VMF-212. (Drawing by Richard M. Hill.)

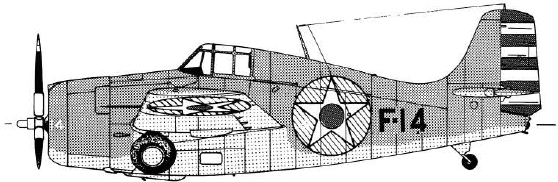

Grumman F4F-3A Wildcat, Bureau Number 3914, F-14 (Fighting Six) as flown on 1 February 1942 by Lieut. (jg) Wilmer E. Rawie, USN. In this aircraft Bill Rawie at 0704 on 1 February 1942 scored the first aerial victory by a U.S. naval or Marine Corps fighter pilot in the Pacific War. Over the island of Taroa in the Marshalls, Rawie shot down the Mitsubishi A5M4 Type 96 fighter flown by Lieut. Kurakane Akira of the Chitose Air Group. This F4F-3A is marked in general accordance with the 23 December 1941 specifications ordered by ComAirBatFor, with large roundels and striped tail. BuNo. 3914 had been flown by VF-6 in the summer of 1941, but was with VF-3 at NAS San Diego on 7 December 1941. It served on board the Saratoga during the abortive attempt to relieve Wake Island, but was reassigned to VF-6 on 2 January 1942. Taroa was its first and only combat. On 14 February it was transferred to VF-2 and ended up in VMF-212 on 29 April 1942. (Drawing by Richard M. Hill.)

Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat, Bureau Number 4031, F-15 (Fighting Three) as flown on 20 February 1942 by Lieut. Edward H. O’Hare, USN. This is the airplane which “Butch” O’Hare flew on his Medal of Honor flight off Rabaul in which he was credited with five Japanese bombers. Its actual side number has long been in dispute. This side number (F-15) is noted in a contemporary source (Capt. Burt Stanley’s diary), and the bureau number comes from O’Hare’s own logbook still retained by his daughter, Kathleen O’Hare Nye. Butch also flew 4031 in combat on 10 March 1942 in the Lae–Salamaua raid.

Even aside from its glorious association with Butch O’Hare, 4031 had a most interesting history. Originally assigned to VMF-211, it remained behind at Ewa when the marines left on 28 November 1941 for Wake Island and survived the devastating Japanese attack on Oahu. On 15 December it was transferred to VF-3 and became O’Hare’s favorite mount. After VF-3’s return to Pearl, 4031 next served with Paul Ramsey’s VF-2 at Coral Sea and became one of only six VF-2 F4Fs to survive that battle, taking refuge on board the Yorktown on 8 May. Thereafter VF-42 had it until mid-June 1942, when it went to Marine Air Group 23. Used in a training role, it finally became a strike on 29 July 1944. If only this F4F-3 could have been preserved! (Drawing by Richard M. Hill.)

Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat, Bureau Number 2531, F-2 (Fighting Forty-two), as flown on 8 May 1942 by Lieut. (jg) E. Scott McCuskey, A-V(N), USNR. BuNo. 2531 was an early production F4F-3 that operated only with VF-42, being assigned to that squadron even before its formal conversion from VS-41 to VF-42 on 15 March 1941. It served with VF-42 on board the Yorktown from June 1941 until the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942. Scott McCuskey flew it the morning of 8 May 1942 in the attack on MO Striking Force and shot down a Zero near the carrier Shōkaku. Separating from the rest of the VF-42 escort, McCuskey found his way back to Task Force 17 and at 1255, low on fuel, took refuge on board the damaged Lexington. There F-2 remained, as the Lexington first burned and exploded, then sank. (Drawing by Richard M. Hill.)

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat, Bureau Number 5093, F-23 (Fighting Three) as flown the morning of 4 June 1942 by Lt. Cdr. John S. Thach, USN. One of the classic fighter combats of the Pacific War took place the morning of 4 June 1942 at the Battle of Midway, when VF-3’s six escorts tangled with the Zeros of the Japanese carrier force. Jimmy Thach flew this aircraft in the action which saw him shoot down three Zeros and first use his “Thach Weave” in combat. His F4F-4 sustained slight damage in its engine during a head-on run with a Zero, but 5093 brought Thach back safely to the Yorktown. There it had to be left after the flattop was bombed and later torpedoed by the Japanese. Salvage crews the morning of 6 June pushed 5093 over the side to reduce top weight on board the stricken Yorktown, but it was all for naught. The carrier sank on 7 June after being torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. BuNo. 5093 was originally assigned to Fighting Eight on board the Hornet and participated in the Tokyo Raid. Upon the task force’s arrival at Pearl Harbor, 5093 went to CASU-1 and was allocated on 26 May to VF-3 in the process of fitting out for Midway. (Drawing by Richard M. Hill.)

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat, Bureau Number 5089, F-17 (Fighting Eight) as flown on 4 June 1942 by Ens. Stephen W. Groves, A-V(N) USNR. BuNo. 5089 was part of a batch of eleven F4F-4s allocated on 29 March 1942 to VF-8 at NAS Alameda just before the Hornet sailed on the Tokyo Raid. Steve Groves flew this aircraft on combat air patrol the morning of 4 June 1942 at the Battle of Midway and helped defend the Yorktown from the attack of the Hiryū dive bombers. He was credited with one bomber destroyed, but himself was shot down and killed. Some Hornet records and posthumous entries in Groves’s own logbook indicate that he was flying BuNo. 5131 at the time of his death, but that is a clerical error. Groves ditched on 1 May in 5131 and was rescued by the destroyer Monssen. Strong evidence points to 5089 as the airplane Groves flew on 4 June. (Drawing by Richard M. Hill.)

From the fall of 1941 into February 1942, the Grumman Corporation at Beth-page, New York continued to paint its production aircraft, particularly F4F-4s, according to scheme 23350-2. This called for finished aircraft to be colored all light gray (necessitating a repaint by receiving units of upper surfaces to blue-gray). Wing circles (on upper left and lower right wing panels only) were fifty inches in diameter, while the fuselage insignia were only twenty inches in diameter and placed low and well aft on the fuselage. The first batches of F4F-4s received at NAS Pearl Harbor in February and March 1942 were marked in this manner. They went first to VF-2 and then in late March to VF-6, which had the distinction of the largest, then the smallest fuselage circles in the fleet.

The Bureau of Aeronautics evidently thought its 5 January letter inadequate for remarking aircraft. On 6 February it issued another that superseded everyone else’s orders.6 The only change involving the national insignia was to increase the fuselage circles to the maximum diameter possible, but not to exceed sixty-five inches. The letter also called for the squadron designations to be painted on the side of the fuselage as before: squadron number, class of squadron (F for fighting), and plane number within squadron. Also the plane number was to be painted “on each half of the wing with the inboard edge of the numeral at a distance from the edge of the fuselage equal to one half over the overall width of the fuselage in plan view.”7 In other words, the numeral was placed on the top and bottom wing panels, where most of the carrier squadrons were already putting it.

The BuAer 6 February directive was interpreted in a number of ways. NAS Alameda on 26 February began providing F4Fs with thirty-six-inch fuselage circles.8 The Grumman Corporation in late February or early March initiated scheme 23350-4 for the F4F-4s and F4F-7s, which called for blue-gray on upper surfaces, light gray on lower surfaces. Fuselage identifications (bureau number, model number, service identification) were in white. Wing stars (now on all four panels) remained at fifty inches in diameter, and Grumman began putting circles almost that big on the fuselages as well. Striped rudders consisted of six red and five white stripes. It appears that the first F4F-4s received in mid-April at Pearl and delivered to VF-3 were marked in this fashion.

In March and April, the fighting squadrons in the Pacific gradually implemented parts of the 6 February BuAer pronouncement. Fuselage circles especially were affected, their diameters being increased or decreased to a medium size as necessary. The last to do this was VF-6 in mid-May. On 29 April, Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, shore representative at Pearl for Carriers, Pacific Fleet (the new designation of AirBatFor) directed that squadron numbers and air group commander markings be deleted for security reasons.9 Except for some of VF-6’s F4F-4s, all of the fighting squadrons had long since removed their numbers from their aircraft. Fighting Six complied in its May repaintings.

The reason why the Navy’s planes were repainted in the first place involved recognition by friendly forces; but in that regard, the new schemes began to develop problems of their own. On 9 April, Vice Admiral H. F. Leary, commander of the ANZAC Force in Australia and New Zealand, informed CinCPac that in April the Army Air Force units in the Southwest Pacific intended to paint out the red circles in their white stars to prevent confusion. It appears the Aussies were letting go at anything red on an aircraft, thinking it was a Japanese “meatball.” Admiral Nimitz agreed, and on 24 April forwarded a recommendation to Admiral King that the red circles and striped tails on naval aircraft be painted out. He requested early action on this from Washington.10

Meanwhile, the Army Air Force went ahead with its plans, receiving approval in Washington to standardize insignia of the Army and Navy. On 8 May, the commanding general of the Hawaiian Department passed on to Admiral Nimitz the decision that as of 15 May, all U.S. military and naval aircraft would no longer have the red ball within the stars or striped rudders. The carrier squadrons began repainting their aircraft around 10 May.11 The rudders were painted blue-gray to match the camouflage scheme. That was the last major repainting of naval combat aircraft for a long time, and the confusion of the first six months regarding aircraft markings was now ended.