![]()

![]()

![]()

Naval Flight Formations and the “Thach Weave”

![]()

Inseparably associated with Lt. Cdr. John S. Thach and his Fighting Three is the first use of the famous “Thach Weave” at Midway. Another renowed naval fighter tactician, Lt. Cdr. James H. Flatley, Jr., called it “undoubtedly the greatest contribution to air combat tactics that has been made to date.”1 After 1942, virtually every fighting squadron adopted the weave wholeheartedly, and Army Air Force pilots used it as well. The “Thach Weave” retains its utility today, as American pilots learned in jet duels over North Vietnam, where they had to “rediscover” the tactic. Basically the “Thach Weave” is a means for two or more aircraft to cooperate in mutual lookout and defense against opposing fighters. It is one of the few really important air tactical maneuvers that can be attributed directly to a single innovator who created and first used it in combat. The best way to sketch the origin of the weave is to discuss the development of the fighting squadron combat formations.

Shortly after the outbreak of the European War, the U.S. Navy decided to reevaluate its fighter tactics. In October 1939, Vice Admiral Charles A. Blakely (Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force—ComAirBatFor) directed that two fighting squadrons, Lt. Cdr. Truman J. Hedding’s Fighting Two and Lt. Cdr. William L. Rees’s Fighting Five, test the concept of using two-plane sections as the basic aviation flight formation. Up to that time the fighting squadrons flew three-plane sections comprising section leader and two wingmen. This formation was cumbersome for single-seat aircraft, as the wingmen had to concentrate mainly on keeping station and preventing collisions with each other in tight turns. This adversely affected their lookout potential, as the fighter pilots were usually busier watching each other than looking for enemy planes.

Test results for the two-plane section were highly favorable, and the pilots were most enthusiastic. The formations turned with ease, and lookout was greatly improved. Once they flew two-plane sections, the pilots could not understand why they had not made the change long before. Going further, Hedding’s VF-2 pilots experimented with flying in a stepped-down position behind the leader, the wingman and all successive planes flying below each other. During the tests, the NAPs used their elderly Grumman F2F-1 biplanes, but soon they were to convert to Brewster F2A-2 monoplane fighters. With the single-wing planes, visibility was better looking up than down; hence there was greater efficiency in a stepped-down formation. The use of the two-plane section stepped-down allowed the wingman to cut inside his leader on all turns—easing considerably his staying in formation. This was a very important development.2

On 26 March 1940, Blakely authorized Fighting Two and Fighting Five to continue the new formation at least until the completion of the annual cruise that June. That month, Hedding prepared a detailed analysis of his tests, but left for a new assignment before it could be submitted. His successor as VF-2’s skipper, Lt. Cdr. Herbert S. Duckworth, was most impressed with Hedding’s conclusions and could add a new wrinkle. He thought it was no longer necessary for the division and section leaders to employ the numerous, complicated hand signals to communicate flight orders to their pilots. In most cases, Duckworth found that just rocking his wings was sufficient to signal turns or attacks to his pilots. Inexplicably the new ComAirBatFor, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, decided that summer to reject immediate adoption of the two-plane section for his fighting squadrons. Despite considerable opposition from above, Duckworth stuck to his guns and retained the formation. He and other enthusiasts kept battling to have the new formation made Navy-wide, but conservatism in the high command prevented that.3

From the great air battles fought over Britain and the Continent, some tactical information filtered down to the carrier squadrons in the Pacific. In March 1941, air advisors of the Chief of Naval Operations learned of the Royal Air Force’s practice of detaching one or two fighters as “weavers” to cover the rear of the fighter squadron from surprise attack. What OpNav did not know was that the British “weavers” usually did not come back! On 27 March, all carrier squadrons were told to test the weaving method of lookout, nicknamed “Charlie” tactics (or contemptuously, “Ass-end Charlie”). Resulting comments from most of the fighting squadrons were caustic, condemning the practice as a waste of fuel.4

In April, Lieut. Thach’s Fighting Three came on board the Enterprise for sea duty. On the cruise he experimented with the “Charlie” tactics. With his squadron deployed in cruise formation on a steady course (such as escort duty), Thach thought the use of a rear patrol and lookout element had some limited value. He deployed the trailing section slightly above and behind the main formation. Each fighter patrolled independently to watch the blind spot of the divisions. These aircraft executed alternate turns of about 30 degrees to the right and left, steadying down after each turn. There was to be no continuous weaving as practiced by the British. Thach communicated his findings to ComAirBatFor in a letter dated 12 May.5 In it he also promised further experimentation, indicating his continued interest in lookout doctrine.

Meanwhile, even ComAirBatFor slowly came to the conclusion that the two-plane section was useful. On 7 July 1941, Halsey issued orders that each fighting squadron henceforth would be organized into three six-plane divisions, each composed of three two-plane sections. Rear Admiral A. B. Cook, commanding the Atlantic Fleet air squadrons, likewise on 10 August told the Yorktown and Ranger fighter pilots to conform to the new organization.6 It was a year too late, but still most welcome.

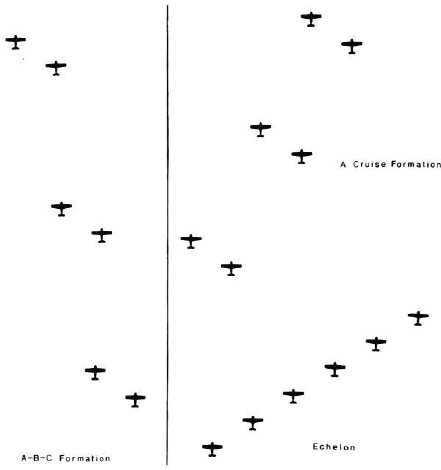

Under the new procedure, the six-plane division utilized formations based on the old USF-74 (Revised) and other doctrine, but modified to take into account two- rather than three-plane sections. While cruising, the division assumed what was known as the “A-B-C formation” (see sketch), sections deployed stepped up at double the normal open order of 300 feet between sections. When approaching a combat area, the division leader usually formed his planes into echelon with the following planes stepped down behind the leader. This permitted all of the pilots to observe the target and bring their guns to bear. Standard open distance between sections was 300 feet, closed distance 150 feet.* The division leader made the tactical decisions, instructing his pilots either to follow for one-division attack in close succession or split to “bracket the target” and hit the enemy from different directions.

Two-plane section formations and turns.

The section comprised leader and wingman. In flight, the leader, in concert with the division leader’s signals, decided what maneuvers the two planes would make, taking care to alert his wingman of what to do and allow for that pilot’s need to stay with him. The wingman’s main function was to support his leader and protect his tail by unceasing vigilance. It was more important for him to stick with his leader than himself shoot during a firing pass, if shooting would force him to separate. This was a lesson that would have to be learned over and over again by overeager pilots who broke tactical contact in air actions. Generally the section flew in echelon with the wingman stepped down below the leader, but always in a position where his leader could see him. Standard close interval between aircraft was 50 feet, standard open distance 150 feet. Making turns, the wingman was to slide inside and under the leader, greatly minimizing station keeping. In actual attack, such as a high-side run and subsequent zoom climb, the interval between fighters was to be no more than 250 to 400 yards.

Six-plane division formations.

The summer of 1941, Thach’s Fighting Three went ashore at NAS San Diego to reequip with Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats. This gave Thach much more opportunity to test new ideas. He liked to simulate various flying formations by laying out matchsticks on the kitchen table of his home in nearby Coronado—often a relaxing diversion before retiring for the night. The next day he would try his ideas in the air. While he was at San Diego, information reached Thach from the Fleet Air Tactical Unit describing the new Japanese Zero carrier fighter. The FATU Intelligence Bulletin of 22 September 1941 gave the Zero a top speed of between 345 and 380 mph (300 to 330 knots), a cruise of between 210 mph and 250 mph (182 to 217 knots), and an armament of two 20-mm cannons and two 7.7-mm machine guns.7 Thach also may have seen other estimates, emanating from Claire Chennault in China. Chennault possessed firsthand experience in battling the Zero. He rated its top speed at 322 mph (280 knots), but more important, warned of the Mitsubishi’s incredible maneuverability and high climb rate (reported variously at 3,500-plus feet per minute, or needing only six minutes to reach 16,000 feet). At any rate, the estimates sketched a formidable opponent, if one gave any credence to them. Thach was inclined to credit the reports he saw, as he felt they appeared to have been written by a fighter pilot. It was not comforting that the potential enemy might already possess a fighter that could outperform the F4F-3s just reaching the squadron.8

Faced with the possibility of encountering fighters that were faster, more maneuverable, and swift climbers, Thach began thinking of tactics to overcome these vital advantages. Out came the matchsticks in earnest. He concentrated on developing a cruise formation that would offer protection en route to battle, the time when his fighters would be most vulnerable to surprise attack from above. In dealing with an attacking fighter, the defender has two basic options: turn away and run, or head into his assailant to counterattack or try spoiling his aim. In fighting a Zero such as described, Thach knew it would be suicidal to break away unless the defender had a hell of a long lead. Thus the crux of the problem lay in developing a maneuver in which the defender, in deciding to stay and fight, could line up a shot on the attacker. Because of extensive training in deflection shooting, Thach felt confident his pilots could score hits, even if offered only snap bursts at fleeting targets.

Early on, the matchsticks proved that two sections of four planes, rather than a whole division of six, were best for engaging enemy fighters. Thach’s first experiments involved a four-plane division flying close formation. This turned out to be ineffective because the fighters had to maneuver together in almost a tail-chase in order to stay together—little advantage over six planes strung together. Next, Thach decided to split the two sections, placing one farther behind the other. The new formation offered some advantages. In dividing the formation into two distinct elements, Thach compelled the attackers to press the assault against either one or the other section, offering the unattacked section a chance to shoot at the enemy when he recovered from his firing pass. However, the sections still interfered with each other and lacked the freedom to maneuver, still being too close for one section to work out a shot on fighters hitting the other.

Thach made his breakthrough when he decided to deploy the two sections abreast of each other at a distance at least equal to the tactical diameter (turning radius) of the F4F Wildcat. Once he assumed this formation, he saw many opportunities for the defender. Being abreast of one another, the sections had good lookout, particularly over the tail of the opposite pair. Thach evolved a lookout doctrine in which the section on the right watched above and behind the left section, and, similarly, the pair on the left observed the tail of the right section. They could warn each other of imminent attacks by signals, hastened by the fact they were already looking in each other’s direction!

In terms of dealing with attacks, all four planes could fire on enemy fighters executing opposite (head-on) attacks. If the enemy charged in from above and behind, one section could turn to shoot at any fighters bouncing the other section. Thach quickly determined that the best procedure was to have the section that spotted an attacker going after the other section, itself turn immediately toward the threatened compatriots. This would be the signal to alert the other section and would also get the two counterattacking planes moving in the proper direction for a shot at the enemy. Seeing the other section turn toward them, the section in danger would know they were about to be attacked. Their reaction would be to turn toward the other section and set up a scissors with them. This maneuver would help spoil the aim of the attackers and give the defenders time to work their counter. If the attacker pulled out early, then the unattacked section would get a side shot at him. If the attacker maneuvered to follow his targets around in their turn, then the unattacked section could line up a head-on run. Now this was mutual defense!

Thach was very excited and eager to present his discovery to the squadron. He arranged for a test, taking four planes with him to act as defenders and assigning four other F4Fs under his protege, Lieut. (jg) Edward H. ( “Butch”) O’Hare, to play the attackers. To simulate the Zero’s supposed superior performance, Thach wired the defenders’ throttles so they could not attain full power, giving O’Hare’s four a definite advantage. He told O’Hare to try several different types of attacks to see how well his new tactics performed under combat simulation. The results were most encouraging. O’Hare found the maneuvers that Thach’s defenders used had both messed up his aim and set up shots by the defenders. He added that it was disconcerting to line up a shot on a target that obviously could not see him screaming in, only to have the quarry swing away at the best moment to avoid his simulated firing! The simplicity of the maneuver lay in the defender’s turning to scissor whenever he saw his other section turn toward him. There was no reason to signal or radio each other for warning or instructions. Likewise O’Hare saw the distinct possibilities for return fire by the defenders, no matter how the attackers tackled Thach’s new formation. No longer was the “Lufberry [sic] Circle” the “only” defensive formation for fighters. Thach wrote up his findings for ComAirBatFor, but Halsey’s staff declined to recommend the new tactic to other squadrons, probably because they failed to understand its potential. They told Thach he could use it. He spent the remainder of 1941 refining the maneuver with Butch O’Hare when they could find time, but for the time being it remained their personal tactic.

On his first combat tour with Fighting Three, Thach had no opportunity to institute the maneuver because he never encountered enemy fighters. On the escort mission to Lae and Salamaua, 10 March 1942, Thach divided his force into two four-plane divisions, with O’Hare flying the second section in his division all ready for a test; but the Japanese did not oblige. Then in April he lost all of his experienced pilots to other duty and had to rebuild Fighting Three from scratch.

In early May on a gunnery flight from NAS Kaneohe Bay, he introduced the five pilots with him to the rudiments of the maneuver, the “beam defense position,” as he called it then. First he strung the division into a tail-chase formation. Making three successive abrupt reversals of course, Thach passed down the line of fighters as if executing a firing pass on the trailing aircraft. After landing, he briefed his pilots, demonstrating how head-on passes could be used by a formation of fighters as a defensive counter. The next few days Thach practiced the weave several times with rookie Ens. Robert A. M. Dibb on his wing and the two NAPs, Mach. Doyle C. Barnes and Mach. Tom F. Cheek, comprising the second section. They worked out the routine. To demonstrate his theory, Thach arranged for two Army Air Force Bell P-39 fighters from the 78th Pursuit Squadron, also at Kaneohe, to make simulated attacks on his four planes. To their chagrin, the Army pilots discovered they could not set up a shot without themselves falling under the guns of Thach’s other section.9 Seven new ensigns joined Fighting Three the third week of May, and Thach had to spend most of his time teaching them the fundamentals of fighter tactics. He had only a few occasions to give them an inkling of how the weave functioned. He was not certain his rookies understood the lookout doctrine; so he told them to radio “There’s one on your tail!” to initiate the scissors with the other section.

Given the hectic preparations to flight at Midway, Thach had no opportunity to introduce his borrowed VF-42 pilots to the weave. He had hoped to fly escort with two divisions, both groups of four led by pilots familiar with the weave (himself and Tom Cheek) who could coach the other two pairs by radio. That did not work. The first combat use of the weave is described fully in Chapter 15 of this book. It proved an enormous success under the harshest of conditions. Thach was able to keep his division together with the weave after the loss of one fighter, and the F4Fs destroyed perhaps four Zeros without further loss to themselves. After his experience at Midway, Thach was more than ever a “believer,” and sought to spread the word to the other fighting squadrons. That summer while on leave, he labored to set down his maneuver in an easily understood form. He incorporated sketches (reproduced here) of the maneuver in a revision of the fighter chapter in USF-74. In an important interview conducted on 26 August at BuAer, Thach stressed that with his maneuver it was possible to keep a four-plane division together and fight as a team:

The left section can watch the tail of the right section and vice versa, you can protect each other by continual motion toward and away from each other . . . firing opposite approaches, shooting Japs off each other’s tails.10

That is just what he and his pilots did at Midway.

Two of Thach’s disciples were posted in June and July to the reorganized Fighting Six under Lieut. Louis H. Bauer. Serving on board the Enterprise, Fighting Six on 7–8 August saw much combat in the skies over Guadacanal, engaging in several sharp fights with Zeros, suffering the loss of four F4F-4s out of ten. In the Enterprise action report, it was acknowledged, as on previous occasions, that the F4F-4 was no match for the Zero fighter in a dogfight. The report noted the best countermove for F4Fs was for:

Thach’s own diagrams (Aug. 1942) of his second countermove (right) and the weave.

. . . each plane of the two plane element to turn away then turn immediately toward each other and set up a continuous “scissors.” Thus when a Zero bears on one of the F4F’s, the other F4F is in position to fire on a Zero.11

This appears to have been a sort of “bastard” version of the weave involving only the two aircraft of a section, rather than a whole division. It would be less effective because the F4Fs had not split out to begin with. Starting in close formation, both fighters using the procedure outlined above would have lacked sufficient room to turn again toward each other for a proper scissors. Probably a product of insufficient understanding of Thach’s tactic, the “bastard” weave as described lacked any reference to the vital lookout doctrine devised by Thach. There is no record that Fighting Six ever tried either the version listed above or the actual weave in action.

Meanwhile Jimmy Flatley took command of the new Fighting Ten and was eager to apply his own tactical ideas and combat experience from the Battle of the Coral Sea. A thoughtful, outstanding fighter leader, Flatley compiled a detailed squadron doctrine revolving around the use of six-plane “flights.” Conferring with Thach in July, Flatley found his ideas fully agreed with his close friend’s doctrine except for the use of four-plane divisions and the weave. Flatley thought his own system was superior. In September, Fighting Ten went out to Oahu and trained at Kaneohe, where Lt. Cdr. O’Hare’s Fighting Three also operated. Flatley worked closely with O’Hare, who had the chance to demonstrate the weave aloft in the course of many practice missions. Butch ably sold his man, and Flatley became fully convinced of the value of the maneuver. Early in October before embarking on board the Enterprise, Flatley made the four-plane flight the basis of his squadron organization and instructed his pilots on the fundamentals of the weave.

On 26 October during the carrier Battle of Santa Cruz, the weave was used for a second time in combat, this time by Flatley personally. He led eight VF-10 F4F-4s on a long escort mission, but Zeros jumped the strike group not far from the American carriers. One of Flatley’s flights, led by Lieut. (jg) John A. Leppla of Scouting Two fame, dived in to engage Zeros, but these planes were themselves ambushed by more Japanese. Two F4Fs, including Leppla’s, were shot down, but the two survivors. Ensigns Willis B. Reding and Raleigh E. Rhodes, used the weave to fend off more numerous Zeros until Rhodes’s engine failed. He bailed out, and Reding managed to return to base. Meanwhile after destroying one Zero, Flatley’s four fighters continued the mission, escorting the strike planes to the target and back. Returning to the Enterprise under intense attack, the strike group had to wait until “The Big E” could take them on board. Circling in the area, low on fuel and ammunition, Flatley’s flight fell under Zero attack, and VF-10’s skipper initiated the weave. The four F4F pilots sustained the weave at only 50 percent power and shook each Zero as it came in. The Japanese were not eager to face the maneuver and pulled off after only a few runs. The four F4Fs landed safely back on board their carrier.

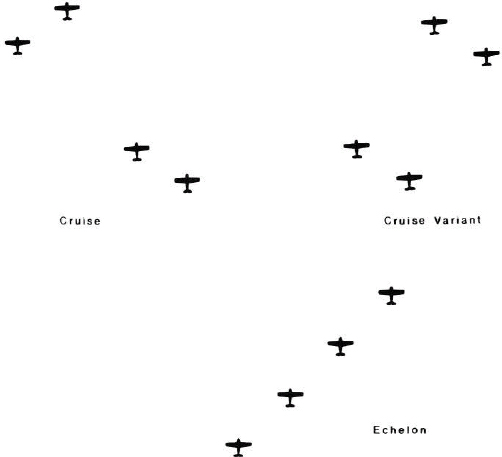

Four-plane division formations.

In his action report for Santa Cruz, Flatley devoted a large section to the maneuver, dubbing it for the first time the “Thach Weave.” He sent a short message of congratulations to Thach as well. Flatley in his report wrote that the “Thach Weave” was “absolutely infallible when properly executed.” He thought the weave was “offensive as well as defensive.”12 Two or four F4Fs working as a team could blunt attacks by more numerous enemy fighters and secure excellent shots. The maneuver could be used by bombers as well as fighters, but would require training and perfect timing to make the weave effective. He enthusiastically recommended that the Navy provide training of the “Thach Weave” for all combat squadrons.

Flatley also provided detailed comments on techniques to be used by F4F-4s in executing the “Thach Weave.” The fighter pilots were to deploy abreast whenever they expected to encounter Zeros. One section was to fly slightly higher than the other. Whenever the enemy attacked one section, the two elements were to turn toward each other for a scissors—the high section in a shallow dive and the low section in a gentle climb. As soon as the fighters under attack swung past their other pair, they were to turn immediately in the opposite direction. Flatley felt it was necessary to reverse turns promptly after scissoring and not let the weavers swing too widely out of support range. Meanwhile, the section not under attack could set up a shot on the Zero and head back after firing or after the enemy had drawn away. The two elements were to maintain the weave while they faced direct attack. Flatley warned the pilots not to let the F4F-4’s speed drop below 140 knots.

The question of escort tactics came to the fore again, and Flatley felt the weave provided the answer. He recommended the escort fighters take station ahead of and about 1,500 feet above the strike planes. If enough fighters were available, they could fly a similar formation behind the attack planes. If ambushed, both elements were to dive in toward the bombers to cut short any Zeros making runs on them; then the escort was to commence weaving over the bombers. Flatley thought the weave provided the best protection for the strike planes:

. . . just your presence over the formation with two units (sections or 4-plane flights) weaving so that someone is always heading toward each flank, will detour the enemy and will keep you in a position to take head-on shots.13

The whole thing boiled down to mutual support and how best to bring this about.

Flatley’s acceptance and enthusiastic endorsement of the “Thach Weave” helped set the stage for its rapid adoption by naval fighting squadrons in subsequent months. Thach himself labored long and hard in late 1942 and early 1943 to produce a series of training films and booklets presenting all of the fundamentals of naval fighter doctrine, including hit-and-run offensive tactics and the “Thach Weave.” Together they spread the word.