![]()

![]()

![]()

“We are in great need of a victory.” The Wake Island Operation

![]()

The first week of the Pacific War saw the United States Pacific Fleet embattled on all sides. On 10 December, Guam’s tiny garrison succumbed, while Japanese air power daily pounded Wake Island. Planners in Washington doubted the fleet’s ability to repel expected invasions of Wake, Midway, and Samoa. There was no question of sending the fleet to relieve beleaguered American troops in the Philippines. Kimmel’s first concern was to protect Hawaii by using his carrier task forces to patrol between Wake, Midway, and the Hawaiian Islands to prevent the return of enemy raiding forces east of the 180th Meridian. Aside from supporting the island garrisons, such patrols would also keep the Lexington and the Enterprise at sea and mobile. The fleet could no longer risk protracted stays by carriers at Pearl Harbor. Kimmel awaited the arrival of the Saratoga from the West Coast; then he could do something for Wake.

Wake’s defenders served as a shining example for the whole Pacific Fleet. From the first day of war, the island garrison, led by a former skipper of Fighting Five, Cdr. Winfield Scott Cunningham, bravely endured severe air strikes. The remnants of Paul Putnam’s VMF-211, crippled during the first surprise attack, fought magnificently with the few Grumman Wildcats they patched together. On 11 December, Wake repulsed a major enemy amphibious attack and sank two destroyers, one by VMF-211. Constant air attrition whittled away the island’s air power, manpower, and supplies. Unreinforced, it was only a matter of time before the garrison would be overwhelmed by a second Japanese invasion.

Kimmel on 12 December consolidated plans to relieve Wake. Of his three carriers, the Enterprise in Halsey’s Task Force 8 was chasing submarines north of Oahu, Brown’s Lexington was headed for Pearl, and the Saratoga likewise was expected in a few days. Kimmel decided to keep Halsey at sea to cover the other two carriers while they shuttled in and out of Pearl. Since the Lexington was scheduled to arrive on 13 December, Kimmel earmarked her to make a diversionary raid on Japanese bases in the Marshalls. This would draw enemy attention away from the actual Wake Island relief force. The Saratoga drew the tough assignment of escorting the Wake relief ships. She would stop at Pearl, top off her oil bunkers, then put out to sea for Wake. On board would be the fighters of VMF-221 to bolster Wake’s air strength, while the seaplane tender Tangier embarked troops, ammunition, supplies, and a vital radar set for Wake’s garrison.

The Lexington rested in port one day, and on 14 December made ready to sail as the nucleus of a new task force: Task Force 11 (the Lexington, three heavy cruisers, nine destroyers, and a fleet oiler) under Brown. His mission involved raids on the Japanese naval base at Jaluit in the Marshalls, although he retained discretion to substitute other targets or withdraw without attacking if necessary. CinCPac set “D-Day” (the day when reinforcements would reach Wake) as 23 December, Wake time (22 December in Hawaii), and Brown was to attack the day before. It was a difficult assignment, as Brown faced with his lone carrier what Kimmel had once intended in his prewar “Marshalls Reconnaissance and Raiding Plan” for two carrier task forces closely supported by squadrons of PBY flying boats.

The afternoon of 14 December, Task Force 11 left Pearl. Shortly before dark the Lexington Air Group flew out to the carrier and landed on board. It had the strength shown in the table—total, twenty-one fighters, thirty-two dive bombers, and fifteen torpedo planes, or sixty-eight aircraft, not all of them operational. Fighting Two embarked twenty-one Brewster F2A Buffalo fighters, only seventeen of which were flyable. Three others on board were awaiting major overhaul, and one needed a right main landing strut. Brown took up a southwesterly heading at 16 knots. On the way out, he encountered Task Force 16 waiting uncomfortably off Oahu.

Delays had postponed the Saratoga’s arrival by one day. On Sunday morning, 14 December, she drew close enough to Oahu to be able to fly off her air group before entering port herself. Thirty-one SBDs fanned out ahead to watch for submarines; then at 1112, the rest of the air group headed for NAS Kaneohe Bay just northeast of Pearl Harbor. Inbound there was a flutter when an Army B-17 Flying Fortress happened upon the formation. Fighting Three closed in belligerently, only to discover its quarry was friendly. The Saratoga aviators settled in at Kaneohe and discovered that Japanese dive bombers and fighters had done quite a job in the last week on the patrol plane base:

Our first glimpse of the damage showed the skeletons of the burned and bombed PBY’s. They had been piled to one side in the week since the attack. The framework of a burned hangar still stood gauntly black in the sunshine. The wreckage of two or three machine-gunned and burned cars stood beside the road. Broken glass had been cleared away but bullet holes still starred the plaster of the B.O.Q.1

Fighting Three just had time to eat lunch before they received orders to fly back out to the ship. The Saratoga would not, after all, enter port until the next day. The carrier took on board all of her airplanes but the marine fighters and the torpedo planes, which spent the night ashore.

Before dawn on 15 December, the Saratoga’s aircraft once again departed for Oahu, this time to NAS Pearl Harbor. Thach’s fighters maintained combat air patrol over the carrier until she made ready to enter port. Satisfied that she was safe, the Wildcats peeled off to land at the naval air station. Suddenly, at 0818, a lookout on board the carrier thought he saw a submarine stalking the flattop four miles south of Barbers Point. The alarm went out by radio, bringing Fighting Three overhead in a hurry. A diligent search by aircraft and destroyers failed to turn up an I-boat; so the fighter pilots headed back to Ford Island, where they were surprised to find no ground crews to service their aircraft. The pilots had to refuel their own planes, and Lovelace had quite a scare when his fuel tank ran over, the nozzle squirting gasoline into his eyes. Luckily he was able to rinse them clean without any ill effects. That afternoon there was time to take a break and a closer look at the sad wreckage and sunken battleships strewn round the harbor. While the pilots relaxed that evening, the Saratoga’s first combat assignment began to take form.

The Wake Island relief operation.

As commander of Task Force 14, the actual Wake relief force, Kimmel designated a nonaviator, Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher flying his flag as commander, Cruiser Division Six on board the heavy cruiser Astoria. Fitch, who was slightly junior to Fletcher, became the air task group commander. Fletcher’s Task Force 14 comprised the carrier Saratoga, three heavy cruisers, eight destroyers, the elderly fleet oiler Neches, and the seaplane tender Tangier. Because of the Saratoga’s delayed arrival, Kimmel expedited matters by having the Tangier and the Neches depart on 15 December. With its faster cruising speed, the rest of the task force could easily overtake them in a few days.

Fletcher’s primary task was to see that the reinforcements on board the Tangier and also the marine fighters on board the Saratoga arrived at Wake safely. Ideally, the Tangier was to discharge her troops and cargo, then embark evacuees from Wake and return to Pearl; but there was always the chance she just might have to run up on the beach at Wake. Kimmel postponed D-Day for twenty-four hours, setting it as 24 December, Wake time.2 This meant that during the daylight hours of 24 December, the Tangier and three destroyers were to arrive at Wake. Presumably the marine fighters would fly off the Saratoga early that morning, and there evidently were provisions for operating one of the Saratoga’s two dive bombing squadrons from Wake as well, at least on a temporary basis. Meanwhile, Fitch’s carrier aircraft and the marine fighters from Wake had to maintain control of the air space surrounding the vulnerable atoll. CinCPac estimated that the Tangier might require two days at anchor off Wake to complete unloading and loading. That placed an extremely heavy burden on the fighters, both naval and marine, whose services were critical to the success of the operation. Fletcher’s oiler Neches was old and slow, top speed only 12.75 knots, but she was the only one available. Brown took the swifter Neosho with Task Force 11, but he had more ocean to cross in less time than allotted to Fletcher. Even hampered by the slow rate of advance, Fletcher could expect to reach Wake on schedule. He had the option to fuel at his discretion; obviously this meant refueling just before he expected contact with the enemy. Task Force 14 faced no easy task if the enemy mustered any real opposition.

The night of 15–16 December the pilots of Fighting Three slept on board “Sister Sara” berthed off Ford Island. Early the next morning they saw the fighters of VMF-221 rehoisted on board the carrier. Given the fragile nature of the Brewster Buffalo and the infrequent carrier landing experience of the marine pilots, no one wanted to risk any damage to the fighters. Destination was as yet unspecified, but it was difficult to dismiss Wake from one’s mind. Reporting ashore to NAS Pearl Harbor, Fighting Three reclaimed their planes and stood dawn alert. Later that morning there was time to check out rookie pilots Lee Haynes, Jack Wilson, and Edward (“Doc”) Sellstrom in Grumman F4F Wildcats. Thach had drawn two additional fighters from the AirBatFor pool, giving Fighting Three only thirteen F4Fs in all: ten F4F-3s, two F4F-3As and the XF4F-4, an early F4F-3 modified as an experimental, folding-wing version of the Wildcat. It was a sad commentary on naval aviation preparedness that Thach had to embark on a major combat mission with barely more than half a squadron of airplanes, one of which was on strength just for tests! The green pilots, inexperienced as they were, gave their elders more worries when, during field carrier landing practice, two of them managed to ground-loop their frisky mounts. This was an easy thing to do because of the Wildcat’s narrow undercarriage. Both aircraft suffered scraped wingtips. Maintenance crews hurriedly repaired one Grumman, but they had to rush the other dockside to be hoisted on board the Saratoga before she sailed. They just made it. At 1215, the carrier got under way.

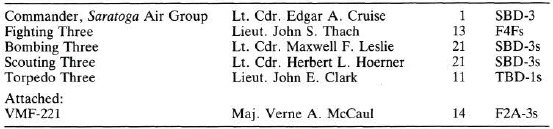

Lt. Cdr. Cruise assembled the Saratoga Air Group at NAS Pearl Harbor, and later that day led them out to the carriers, landing on board a half hour before sunset. The group’s composition (shown in the table) was twenty-seven fighters, forty-three dive bombers, and eleven torpedo planes, eighty-one aircraft in all, but not all were operational. The figures for fighter strength are deceptive. The marines were to transfer to Wake, leaving the Sara only thirteen fighters with which to protect the task force and escort strikes.

Two days out of Pearl, Brown’s Task Force 11, en route to attack the Marshalls, underwent a rather bizarre experience. At dawn on 16 December, the Lexington launched twelve SBDs to fly in pairs a routine search 100 miles ahead of the task force. Not long before 0800 there came the electrifying report that two of the SBDs had encountered a Japanese carrier bearing 210 degrees, distance 95 miles from the task force. No further messages were forthcoming from them. Brown and Sherman deduced that Japanese fighters had intercepted the two search planes, and Brown detached his oiler Neosho, sending her away from danger. Excited by the opportunity to sink an enemy carrier, he later remarked it was the “chance of a lifetime.”3 The Lexington at 0813 scrambled ten F2As from Fighting Two as combat air patrol, then started spotting a strike force for takeoff. Beginning at 0924, she launched sixteen dive bombers, thirteen torpedo planes, and seven fighters, all led by the group commander, Bill Ault.

During the launch of the strike group, the two SBDs that had originally spotted the enemy carrier returned to the task force. Once the flight deck was clear and the attack planes were en route to the target, the Lex at 0933 brought the two on board. Taken before “Ted” Sherman, the two pilots, Ens. Mark T. Whittier and Ens. Clem B. Connally of Bombing Two, both stated they had dive-bombed the carrier, but claimed no hits. As related by the two ensigns, the target stayed strangely dead in the water and gave no return fire. It was puzzling indeed. Finally someone remembered that on 7 December a naval tugboat towing a dynamite barge to Palmyra Island had received orders to cut it loose and return to base. Evidently that barge was the “carrier” so vigorously assaulted by the two SBDs. Sherman at 1143 somewhat sheepishly signaled Brown on board the Indianapolis that the target was a drifting barge.

Searching the target area thoroughly, Ault’s flyers certainly found no carrier, and somewhat mystified they returned to base. The Lexington at 1325 recovered the attack planes, then despatched ten SBDs to look for the barge. They also could not locate it. Fighting Two flew CAP until near sunset. The two ensigns who had bombed the “carrier” had great difficulty surmounting the sarcasm of their fellow pilots, but they adamantly maintained that what they had attacked was indeed an enemy flattop. To add to the comedy of errors, the Neosho had disappeared over the horizon to escape the enemy “carrier,” and no one knew precisely where she was. Brown dared not break radio silence to contact her. The next day the dawn search located her 41 miles to the southwest, but the afternoon search failed to sight her. Finally Brown roped in his errant oiler after dawn on 18 December and made ready to fuel before commencing his final approach to the target.

The morning of 17 December, the Saratoga and her escorts, one day from Pearl, overtook the Neches and the Tangier, uniting Task Force 14 for the first time. Fletcher set course for Wake at his oiler’s best sustained speed, 12.75 knots. On board the flattop, Captain Archibald H. Douglas spread the word among the officers that the Sara was bound for Wake. The response was overwhelming, as everyone was proud of Wake’s gallant defense. In the wardroom, someone put up a chart with Wake clearly outlined as the objective toward which the task force’s track slowly inched. Fighting Three could not be more jubilant over the opportunity for early combat, especially at Wake. For the next several days, there would be no flying for the fighters, only the inevitable Zed II alerts. No matter, for each day the sun dipped into the ocean straight ahead of the Wake-bound ships.

Meanwhile, momentous events transpired at Pearl Harbor. By order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Navy relieved Admiral Kimmel of his command pending a court of inquiry on the Pearl Harbor attack. The new CinCPac was Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, but he could not possibly reach Pearl Harbor and take command before the last week of December. On 17 December, Vice Admiral William S. Pye, commander of Battle Force, became temporary commander-in-chief, United States Pacific Fleet, pending Nimitz’s arrival. Pye’s first concern, naturally, was the Wake Island operation already in progress. Fleet intelligence, trying to rebuild its estimates of what was going on in the Pacific, began to detect radio communications between Japanese land-based air units operating out of the Marshalls and powerful carrier forces evidently in the area. Wake’s air besiegers flew from bases in the Marshalls. These messages seemed to indicate that the enemy had hedged his bets by assigning strong carrier reinforcements to support a second, more massive assault on the stubbornly held atoll. On 18 December (Hawaiian time), the link became more definite, when decrypts tied the Japanese 8th Cruiser Division and 2nd Carrier Division (both identified as part of the Pearl Harbor Attack Force) with the Fourth Fleet in the Marshalls. That command was responsible for the capture of Wake. One message hinted of the presence of the 5th Carrier Division as well, perhaps in the eastern Marshalls. This, if true, appeared to place four Japanese carriers at the disposal of the commander attacking Wake. Pye forwarded these estimates to Brown and Fletcher, fully remembering that Kimmel’s original plans were predicated on not encountering strong opposition.

Brown on 18 December also learned from the acting CinCPac that the Japanese had apparently set up a seaplane base at Makin Atoll in the Gilberts and also occupied Tarawa south of there. In order to approach Jaluit, his primary objective. Brown would have to pass within search range of Makin and risk early detection. This could bring down on Task Force 11 not only air attacks by land-based bombers, but also counterattacks by enemy flattops possibly in the area. Task Force 11 spent 18 and 19 December fueling while slowly closing Jaluit. On 19 December Brown detached the Neosho to wait in safer waters. Weighing greatly on his mind was the necessity of skirting Makin in order to attack Jaluit.

For Paul Ramsey’s Fighting Two, the cruise so far had proved largely uneventful, but the excitement was building at the thought of going into combat in a few days. The nineteenth of December turned out to be a day for photographs, first of the assembled squadron draped over the wings of two Brewster Buffaloes, then a group shot of the pilots (the NAPs in their denim fatigues doubling as flight gear), and finally individual poses by pilots in front of their aircraft. Little did Fighting Two know it would be months before most of them even saw the enemy!

With his other two carrier task forces now at sea, Kimmel had thought it wise to bring Halsey’s Task Force 8 back to Pearl for resupply and rest. On 16 December the Enterprise sent her air group to NAS Pearl Harbor, then made ready to enter port. Fighting Six contributed eleven Wildcats for the flight, while four others patrolled over the carrier until she was safely in the ship channel. For those pilots flying into Pearl, thoughts of the debacle on the night of 7 December were uppermost: “The long way in past all the batteries still gives everyone a thrill.”4 The pilots had a free afternoon to poke around Ford Island and look at Japanese aircraft shot down during the raid. What they saw did not impress them. Rejoining the squadron was Dave Flynn, survivor of the tragic 7 December incident.

On 17 December, Fighting Six squared away new pilots who had ridden the Saratoga across from San Diego: Ensigns David W. Criswell, Howard L. Grimmell, and William M. Holt. They and the newly acquired Rad. Elec. Bayers practiced field carrier landings in Grumman F4F Wildcats. Even that training had to be curtailed the next morning for lack of fighters. McClusky had to turn over to Fighting Three, pending their return from Wake, no fewer than three F4Fs, but in turn received two others, one of which was Hermann’s old F4F, repaired after being shot up on 7 December. From the AirBatFor pool, Fighting Six also scrounged a stray Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo left ashore by Fighting Two. It was one of two McClusky was supposed to get. This time he ended up with fourteen F4F Wildcats and one F2A Buffalo. The squadron was to embark the next day. Lieut. (jg) Mehle’s VF-6 engineers spent the night in a Ford Island hangar getting the newly acquired aircraft ready for duty.

The “Chiefs” of VF-2, l to r: T. S. Gay, Paul Baker, Gordon Firebaugh, Hal Rutherford on board the Lexington, 19 Dec. 1941. (Capt. G. E. Firebaugh, USN.)

VF-2, 19 Dec. 1941. (Cdr. T. F. Cheek, USN.)

Fighting Six at daybreak on 19 December turned out on alert. The Enterprise sailed as part of Halsey’s Task Force 8. His orders were to operate south of Midway and westward of Johnston in order to support the two carrier task forces about to engage the enemy. Pye wanted Halsey to act as a backstop should the Japanese pursue either Brown or Fletcher. McClusky that morning led twelve fighters out to the carrier, including the one F2A Buffalo with VF-2 veteran Ed Bayers flying her. After two and a half hours of tiresome circling, all aircraft landed safely. With the three fighters already on board the Enterprise, Fighting Six for this cruise counted eleven F4F-3As, three F4F-3s, and one F2A-3. Again, a fighting squadron had to sortie without attaining full aircraft strength. The VF-6 pilots had no dope as to the objective, only that they were west-bound.

The nineteenth of December was a day of anticipation for Fletcher’s Task Force 14 plodding along at the Neches’s best speed. Ahead the skies grew ominously overcast. Squall lines formed, and the seas turned rougher. The noon position report placed the task force 1,020 miles east of Wake and five days from the objective. Unfortunately, it began to appear that Japanese carriers might be even closer.

The morning of 21 December (Wake time), the Japanese added a definite new twist to the problem of reinforcing Wake. Just before dawn, forty-nine strike planes from the carriers Sōryū and Hiryū roared down on Wake to bomb and strafe suspected strong points with impunity. There was no warning, nor was there air opposition from VMF-211. Lacking radar, the island command had no idea the raiders were coming. The eighteen Zero fighters, twenty-nine dive bombers, and two torpedo planes suffered no losses, and their presence over Wake sent reverberations all the way back to Washington.

The Japanese carriers were there because of Fourth Fleet’s cry for help following the abortive 11 December invasion. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, commander of Combined Fleet, on 15 December detached from Nagumo’s Pearl Harbor Attack Force a powerful striking force of two carriers, two heavy cruisers, and two destroyers. They formed the Wake Island Attack Force under Rear Admiral Abe Hiroaki, and his air task leader was Rear Admiral Yamaguchi Tamon, commander of the 2nd Carrier Division (the Sōryū and the Hiryū). Yamaguchi’s air groups comprised thirty-two Zero fighters, thirty-two dive bombers, and thirty-six torpedo planes, all manned by crack aviators. From the west, Abe’s ships had descended on Wake and on 21 December launched their strikes from about 200 miles away. After recovering aircraft, Abe steamed southeast toward the ships of the 2nd Wake Invasion Force, which that day had sortied from Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshalls. Operating southeast of Wake was Rear Admiral Gotō Aritomo’s Marshall Area Operations Support Force with four heavy cruisers and two light cruisers. Gotō’s task was to protect the invasion convoy’s right flank and also to watch (presumably with his cruiser floatplanes) for the possible appearance of an American task force trying to reinforce Wake.

Aware that at least one enemy carrier lurked off Wake, Pye in his uncomfortable role as caretaker CinCPac had good reason to reevaluate the basic plan. Significantly, the enemy appeared to be increasing his air strength, land- and carrier-based, in the critical Marshalls–Gilberts region. This boded ill for Task Force 11’s diversionary raid on Jaluit, as the enemy might well detect Brown on his way in. Best to cancel the Jaluit raid altogether. Pye preferred bringing Task Force 11 north to support Fletcher’s Task Force 14 near Wake. According to CinCPac estimates, beginning D + 2 (26 December, Wake time), Brown should be able to put planes over Wake. Halsey with Task Force 8 (the Enterprise) was bound for Midway. He would act as the reserve. The afternoon of 20 December (21 December, Wake time) Pye ordered Brown to cancel the raid on Jaluit and head for Wake. He was most concerned that Brown and Fletcher fuel before going into action, as he especially feared a running battle with Japanese carriers in which fuel shortage or damaged vessels could mean disaster for the Pacific Fleet.

Ironically, the same day Pye decided to call off the Jaluit raid, Brown on his own had concluded that Jaluit would be too tough. Instead he opted to attack Makin and Tarawa in the Gilberts, the air strikes to take place the morning of 22 December (East Longitude Date). At 1600 on 20 December, he announced his new plans to the task force. Interestingly, the attack plan called for the SBD dive bombers to be relaunched as supplementary combat air patrol after returning from the strike. Six to eight SBDs were to deploy in each quadrant around the Lexington, circling at 1,000 to 3,000 feet and one mile out from the screening vessels. This was the first manifestation of an idea that was a favorite of Sherman.1 He felt that SBDs could cope with enemy torpedo planes, a concept that he would pursue in the future. Almost simultaneously with Brown’s issuing of his Makin–Tarawa plans, his flagship Indianapolis copied the CinCPac despatch canceling the Jaluit strike. At 1738 Brown changed course to the northwest and headed off at 16 knots. He was still many days from the crucial area, as it was necessary for him to skirt the Marshalls to avoid enemy air searches before heading directly toward Wake.

The morning of 20 December, Fletcher’s Task Force 14 with the Saratoga crossed the International Date Line, propelling time ahead to 0845, 21 December. Fletcher was now on the same side of the line as Wake and around 700 miles east of there. The weather was forbidding, with a gray overcast. That day the Saratoga’s SBDs flew intermediate and inner air patrol, but there still was no flying for Fighting Three. That afternoon, Fletcher received a despatch from Pye that ordered Task Force 14, except for the Tangier and her escorts, to stay more than 700 miles from the Japanese air bases at Rongelap in the Marshalls. Pye did not want the Saratoga to get too close to Wake, which was a focus for Japanese bombers flying from the Marshalls. If Fletcher kept more than 700 miles from Rongelap, enemy land-based air could neither sight nor attack him. At 2000, Task Force 14 was 635 miles northeast of Wake. Fletcher held to a northwesterly course to take the task force well north of Wake in order to approach the island from that direction.

The pilots of Fighting Three awoke before dawn on 22 December to prepare for flight duties, the first since landing on board near Oahu. The weather, they discovered, was worse than before. The Sara pitched and rolled in turbulent seas that even washed over her massive bow. Lovelace drew the early morning patrol, taking six Grumman F4Fs aloft at 0634. His mission was to cover the task force while Fletcher fueled his destroyers from the oiler Neches. Cross swells combined with 16- to 24-knot winds parted several oil hoses and greatly impeded the process. Fletcher had to swing north, then northeast to try to ease sea conditions. Task Force 14 at 0800 was 518 miles northeast of Wake. They were getting nowhere or even losing a little distance during fueling, but Fletcher still held to schedule to arrive at Wake on D-Day, 24 December. Fueling delays, however, cut deeply into what time reserve he had. Still, he had no choice but to continue fueling so that his destroyers would have the fuel to steam and fight, if need be, for several days.

By midmorning, Lovelace’s fighters started to have fuel problems of their own. The Saratoga readied Thach’s 1st Division to relieve them. His six F4Fs took off at 1021, and plane handlers respotted aircraft forward on the flight deck in order to land Lovelace’s CAP. Unexpectedly, Thach returned to the carrier at high speed, flew along the flight deck, and gave the emergency deferred forced landing signal (wheels up, tail hook down). His wingman was in trouble. Lieut. (jg) Victor M. Gadrow’s Grumman (3-F-12) acted up, and he tried to reach the carrier for a quick landing. Suddenly the aircraft appeared to lose power and fall away. It struck the water with a great splash about 1,400 yards off the port quarter. The F4F sank immediately in the rough seas. Racing to the scene, the destroyer Selfridge, acting as plane guard, found nothing. Fighting Three had suffered its first casualty of the war. Vic Gadrow was a 1935 graduate of the Naval Academy and had but recently transferred to aviation after almost five years on board the battleship Colorado. Earning his wings in the spring of 1941, Gadrow had reported to Fighting Three, where he was learning fast. Thach had earmarked him as a section leader. The loss of pilot and aircraft left Fighting Three with twelve Wildcats.

That same morning, 22 December, aircraft from the Sōryū and the Hiryū again attacked Wake, but this time a surprise awaited them. Two VMF-211 pilots, Capt. Herbert C. Freuler and 1st Lieut. Carl R. Davidson, were aloft and in position to intercept. The enemy strike group consisted of thirty-three Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 carrier attack (torpedo) planes [KATE] from both carrier air groups. Escorting them were six Zero fighters. The carrier attack planes formed up by divisions (chūtai) at 12,000 feet to execute horizontal bombing runs over Wake, the six fighters covering them from 18,000 feet. Freuler charged after six Japanese planes in close formation at 12,000 feet. He thought they were Zero fighters, but actually they were a chūtai from the Sōryū Carrier Attack Unit. Diving in, Freuler shot down two bombers, the last in a furious head-on run.2 Exploding just in front of the F4F, debris from the second Japanese plane so damaged Freuler’s Wildcat that he had to run for base. Before he could get clean away, a real Zero jumped his tail and riddled the F4F with gunfire, wounding Freuler. He crash-landed on Wake and walked away, although his airplane was done for. Davidson immediately tangled with some of the Zeros, and was seen no more. The bombers plastered suspected battery positions, then departed southwest toward their carriers. Wake no longer had any fighter support.

Fletcher spent the afternoon of 22 December fretting about fueling delays in the face of worsening weather. At noon, he had resumed his slow advance to the northwest, but conditions permitted only four of his destroyers to take their drink of oil. He hoped to fuel the rest early the next morning before commencing the second phase of the operation—sending the Tangier and her escorts to Wake. At 2000, Task Force 14 was 543 miles northeast of Wake. During the night Fletcher made good some of the miles lost because of the refueling and prepared to resume fueling at first light the next day. Late that evening, Fletcher received another message from CinCPac revealing Pye’s misgivings about the Wake operation. Fletcher was not to take the Saratoga any closer than 200 miles to Wake. He could still fly the marine fighters off to Wake during the approach, but now they would have to protect the island and also the Tangier’s run to the objective. There was no prospect that VF-3’s fighters, now numbering only a dozen, could cooperate with VMF-221 after they reached Wake. Thach’s fighters would have to remain behind to defend Task Force 14.

Even so, the Japanese were not about to give the Pacific Fleet the opportunity to reinforce Wake. In the early hours of 23 December, the 2nd Wake Island Invasion Force drew up near the atoll and disembarked special naval landing troops. They stormed ashore around 0230, and by dawn, despite a gallant defense, the Wake garrison was sorely beset. At 0700, the first of twenty fighters, twelve dive bombers, and twenty-seven carrier attack planes from the Sōryū and the Hiryū appeared over Wake and pounded any signs of resistance that popped up ahead of advancing Japanese troops. Except for tiny Wilkes Island where the marines had virtually annihilated the invaders, the Japanese by 0800 had subdued all opposition. The battle for Wake was over.

Radio reports from Wake had alerted CinCPac of the presence of invasion forces. At Pearl Harbor, Pye convened his staff before dawn. They generally agreed that with the forces at hand, Wake probably could not be saved. The enemy was bound to be much stronger for the second attempt to capture the atoll. Intelligence estimated that as many as two carriers, some cruisers, and probably a pair of fast battleships lurked near Wake, although some officers thought there might be only one “small” carrier, the Sōryū.

Given the expected loss of Wake, the question became one of allowing Fletcher to attack the invasion ships clustered around the island. He could attack alone, or later in concert with Brown coming up from the southeast. Captain Charles H. McMorris of War Plans urged that Fletcher make a counterattack, citing a number of pertinent points to support his aggressive advice. Task Force 14 had already fueled (or should have, according to plan) and was ready to fight. The Saratoga this trip wielded two fighting squadrons (VF-3 and VMF-221), and McMorris felt this put the odds “strongly in her favor.”3 A swift carrier raid, he believed, would catch the Japanese unaware, as they did not know of the presence of Task Force 14 in the area. McMorris stressed that at little real risk to the Saratoga, there was a major opportunity to deal the enemy a telling blow and win for the Pacific Fleet a desperately needed victory.

Pye, for one, viewed the situation less sanguinely than did McMorris. Unlike some members of his staff, he thought there were at least two Japanese carrier prowling off Wake and knew that they, in combination with the fast battleship also likely to be out there, would be too much for Task Force 14 to handle Especially so early in the game he did not want to risk the loss of even one of his own carriers. During the deliberations, a despatch from Admiral Stark offered tacit approval of the conservative approach, stating that “Wake is now and will continue to be a liability.”4 Pye later described his feelings:

My conclusion was that if action developed against any but unimportant naval forces at Wake it would be on enemy’s terms in range of shore-based bombers with our forces 2000 miles from nearest base with inadequate fuel for more than 2 days high speed, with probable loss of any damaged ships, and might involve two task forces.5

Thus in Pye’s view anything that Fletcher alone or later with Brown might encounter at Wake either would be too weak to count as much of a diversion, or, far more likely, would be too strong to defeat. Consequently Pye radioed a recall order to Brown and Fletcher, bringing them back to Pearl. Covering their withdrawal would be Halsey with Task Force 8 near Midway.

About 450 miles northeast of Wake, Fletcher’s Task Force 14 before dawn on 23 December monitored some of the island’s invasion reports. The Saratoga readied flight operations for six F4Fs on CAP and an outer air patrol (100-mile search) by twelve SBDs. Thach led his 1st Division aloft at 0628. After sunrise, the Neches resumed fueling the last four destroyers. Fortunately the seas were calmer, and refueling proceeded more swiftly than the previous day. Unaware of CinCPac deliberations, Fletcher continued to prepare for the Tangier’s dash to Wake, to begin on schedule later that morning. The Neches and a destroyer would stand off to the east in safety, while Task Force 14 went in. Fletcher would accompany the Tangier to within 200 miles of Wake and cover her final approach with the Saratoga’s air group. Presumably the marine fighters would take off at dawn on 24 December. On board the Saratoga, there was great anticipation, as the pilots were certain they would pitch into the enemy besiegers of Wake, including “one small carrier”6 skulking off the island.

The first inkling of a major change for Task Force 14 occurred at 0753, when the Astoria copied Cdr. Cunningham’s famous message referring to the enemy on the island: the issue is in doubt. Just two minutes later came CinCPac’s recall order the product of five hours of deliberation at Pearl. Pye had sent it before he received final word of Wake’s fate. According to one source, Fletcher was so exasperated at receiving the recall, that he threw his gold-braided hat to the deck.7 Faced with a direct order, he had no choice but to comply. At 0800, he was still 430 miles northeast of Wake. To facilitate fueling, he turned north, taking advantage of better sea conditions to complete the necessary transfer of oil to his destroyers.

While Fletcher and Fitch stewed over the situation, the Saratoga went on with business as usual. There were relief flights to send off and planes low on fuel to recover. At 0956, Lovelace’s 2nd Division from Fighting Three took off as CAP. Behind the six F4Fs came twelve SBDs from Scouting Three as the forenoon outer air patrol. The dive bomber flown by Lieut. (jg) Harold D. Shrider rolled down the flight deck, but failed to attain flying speed. Circling near the carrier, Lovelace clearly saw what happened. The Dauntless shot out over the bow, but instead of climbing away, it plummeted into the water just ahead of the ship. There was a huge splash, as the SBD disappeared into the ocean. Its tail bounced back up almost instantly, and as the aircraft balanced on its nose, the Saratoga brushed an outstretched wing. Shrider’s SBD sank without a trace. A destroyer hurried to the scene to pick up survivors, but there were none.

Thach landed a few minutes after the mishap and learned of the recall. Reaction was understandably bitter. Everyone felt frustrated at not being able to help the Wake marines and bluejackets. They thought they were wasting a grand opportunity to deal the Japanese a stinging defeat. Talk among the officers had it that the enemy had only “one small carrier” in the area—easy pickings for the Saratoga. With more insight than most, Lovelace wrote in his diary, “The set up seemed perfect for those of us who did not have the complete picture of the strategical situation.”8 He, for one, was willing to give CinCPac the benefit of the doubt.

Lovelace’s attitude was rare among the officers of Task Force 14. Captain Douglas of the Saratoga, for example, urged Fitch to contact Fletcher on board the Astoria and request permission for a raid on Wake the next morning to blast enemy invasion shipping there. Fitch sympathized with those who wanted aggressive action, but he left the bridge because of the “mutinous” nature of the conversation. The orders gave Fletcher no discretion, although he stayed in the area on a slow northerly heading to complete fueling. Fighting Three flew CAP for the rest of the day. At 1730, just before sunset, Fletcher with great reluctance set a southeasterly heading back toward Pearl, a little less than 1,600 miles away. At 2056, CinCPac sent amplifying orders telling Fletcher to retire toward Midway and on Christmas Day to despatch the fighters of VMF-221 to that base. The Tangier, as well, was to proceed to Midway.

Still east of the date line, Brown’s Task Force 11 with the Lexington was about 750 miles southeast of Wake, when at 0745 [22 December] the carrier logged in the recall order. Brown changed course to rejoin the Neosho and fuel on the way back to Pearl. Halsey’s Task Force 8 with the Enterprise was located nearly 1,100 miles east of Wake. He and his minions likewise were disgusted at the turn of events—the spectacle of the United States Pacific Fleet retreating without even contesting the fall of Wake. They thought that before recall the Saratoga had already closed to within striking distance (200 miles off Wake). Fighting Six’s unofficial war diary lamented, “Everyone seems to feel that it’s the war between the two yellow races.”9

What were the obtainable realities of the Wake relief mission? CinCPac set D-Day as 24 December. The authorities at Pearl possessed all of the information available to Fletcher and a great deal more. Fletcher had no authority whatsoever to alter the basic plan without approval. In his “semi-official” history, Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison took Fletcher to task for not scrapping the operational plan when he first learned that Japanese carrier planes had hit Wake (21 December, Wake time). According to Morison’s hindsight, Fletcher should have left the Tangier and the Neches behind and rushed in at 20 knots, so he could surprise the Wake invasion forces at dawn on 23 December.10 Morison ignores the fact that CinCPac specifically expected Task Force 14 to refuel before entering combat. Fletcher fueled in the face of poor sea conditions. Even so, he “expected to carry out the mission and have the Tangier and planes arrive Wake on D-Day.”11

The attack by Japanese carrier planes on Wake and the actual second invasion decisively altered the equation in favor of the enemy. Pye had no way of knowing whether the enemy carriers would loiter around Wake in hopes of trapping an American relief force. Task Force 14 required control of the skies. Critics have failed to realize that the Saratoga alone just was not a match for the Sōryū and the Hiryū. McMorris cited the fact in defense of an aggressive approach, that the Saratoga carried two fighting squadrons. Evidently he was not aware that Fighting Three was sadly understrength (only thirteen F4Fs when it left Pearl), while the marines of VMF-221 were not much better off with fourteen F2A-3 Buffaloes. Complicating matters was the fact that the leathernecks were inexperienced in carrier operations and doctrine; certainly in a desperate battle they could not be counted upon as effective in a carrier situation as an equivalent naval fighting squadron. Once the decision was made by Pye to withdraw, Fletcher had no choice but to obey. Morison unkindly cited in his history a somewhat gratuitous comment by an unidentified cruiser captain who said, “Frank Jack should have placed the telescope to his blind eye like Nelson.”12 These were easy words for someone without the responsibility of command in that particular situation. Pye simply could not risk losing an American carrier at that time. For the Pacific Fleet in December 1941, Wake despite the valor of its defenders was indeed a liability.