![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The fall of Wake brought a lull in active operations to the extent that the Pacific Fleet contemplated no offensive operations for the time being. Pye, ad hoc CinCPac, awaited the arrival of Chester Nimitz. In Washington, Admiral Ernest J. King was assuming the post of Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet (CominCh). A naval aviator (wings in 1927 as a captain), King was a former skipper of the Lexington and in 1938–39, Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force (ComAirBatFor). He had definite ideas about employment of carriers and no qualms about implementing them.

As December came to a close, all three carrier task forces operated west of the Hawaiian Islands. Retiring from the abortive Wake relief were Task Forces 11 and 14. Rough seas dogged both Brown and Fletcher. Halsey’s Task Force 8 received a new mission: protect Midway pending the arrival of the seaplane tender Wright. Pye held to the basic policy of shuttling the carriers through Pearl one at a time. When one carrier task force was in port, the other two would be at sea. Any other course of action would have to wait until the new CinCPac had settled in.

To help bring order out of chaos at Pearl, Halsey on 18 December had sent ashore several members of the AirBatFor staff to handle administrative duties. Important for the carrier squadrons was Cdr. John B. Lyon, structures (aircraft) officer in charge of the materiel office. He handled aircraft allocation and regulations. One of his first concerns involved aircraft markings and how they could be altered to reduce the deplorable number of mistaken-identity shootings. Naval aircraft at that time were painted dark blue on the upper surfaces and light gray underneath. Basic markings comprised small white fuselage stars (in blue circles with central red dots), one on each side behind the cockpit, and similar but larger stars on the wings (upper surface left wing, lower surface right wing). Squadron type and plane markings (in black or white numerals and letters, depending on the squadron [see appendix]) were placed on the fuselage, cowling, and wings. The nomenclature of the fuselage markings, next to the roundels, identified squadron number, type (“F” for fighting), and individual plane number within the squadron. Thus 2-F-1, for example, was the number one aircraft in Fighting Two.

On 21 December, representatives from the Army’s Hawaiian Department and the Pearl Harbor–based Navy’s Patrol Wing Two met to discuss what could be done to assure proper recognition.1 They decided to put stars on all four upper and lower wing surfaces and increased the diameter of those roundels to the full width of the chord. Likewise they proposed increasing fuselage roundels to the maximum size possible. To complete the new color scheme, they also recommended that the aircraft rudders be painted with thirteen equally sized stripes, alternating red and white. With the approval of CinCPac, Lyon two days later issued specific regulations for the carrier squadrons to follow in line with the 21 December conference.2 The planes would look very colorful, if nothing else! Fighting Six’s 1941 Christmas card noted: “pepermint [sic] candy sticks may be viewed on the tails of planes.”3 Squadrons repainted their aircraft according to the ComAirBatFor scheme, but in early 1942 there was a bewildering number of minor changes, which with much shifting of aircraft from one squadron to another led to a somewhat motley look among the carrier squadrons.

Changing insignia, probably VF-6 late Dec. 1941 or early Jan. 1942. (NA 80-G-14451.)

More important than how the fighters looked was the vital need for sufficient numbers of them. Lyon and his counterpart at NAS San Diego, Cdr. Henry R. Oster, advised their superiors to transfer Grumman F4F-3s and F4F-3As from marine fighting squadrons on the West Coast out to Pearl. The marines could more easily obtain more airplanes from Atlantic squadrons currently exchanging F4F-3s for the new folding wing F4F-4s. Thus on 26 December, Oster instructed VMF-111 and VMF-121 to turn in thirty-seven Grummans for shipment to Pearl. They arrived in January–February 1942 and were urgently required in bringing the fighting squadrons up to some semblance of authorized strength.

Brown’s Task Force 11 with the Lexington was the first to return after the futile Central Pacific operations. Heavy seas prevented his ships from refueling and restricted flights. What missions Fighting Two did fly were mostly inner air patrol hunting enemy submarines. During one such, on 26 December and one day from Pearl, VF-2 pilot Harold E. (Hal) Rutherford, ACMM, discovered gasoline leaking into the cockpit of his F2A-3 Buffalo. He headed back to the Lexington and at 1113 requested permission to land. The Lex’s flight deck was not clear, but Rutherford could not wait. The Brewster’s engine sputtered, then cut out altogether. The veteran chief deadsticked 2-F-3 into choppy seas about a mile off the carrier’s port bow. The destroyer Monaghan fished him out suffering only minor injuries. The next day Paul Ramsey led seventeen operational F2As to NAS Pearl Harbor, and Task Force 11 docked there that afternoon.

Fighting Two discovered six new pilots awaiting its return. Lieut. (jg) Richard S. Bull, Jr., a former VF-42 pilot, had just come from Britain, where he had been an aviation observer. The five others were NAPs: Thomas W. Rhodes, RM1c, William H. Warden, AMM1c, Beverly W. Reid, AMM2c, Homer W. Carter, AOM2c, and Wayne E. Davenport, AMM2c. The squadron turned over three F2As to the AirBatFor pool for repairs and reassignment, leaving seventeen on tap. On 29 December the Lexington with the rest of Task Force 11 departed for a short cruise southwest of the Hawaiian Islands. Ramsey took his seventeen F2As out to the ship, but only sixteen made it. Fred Borries in 2-F-5 dropped too fast after taking the landing signal officer’s cut and struck the ramp. His Brewster caromed off the stern and splashed 200 yards off the port beam. The F2A sank swiftly, but the faithful Monaghan recovered Borries, who sustained a cut forehead and bruised left shoulder. This cruise the Lexington Air Group numbered sixteen fighters, thirty-three dive bombers, and fifteen torpedo planes.

The thirtieth of December, the day Admiral Nimitz formally became CinCPac, Fighting Two ran into more trouble: another F2A cracked up on landing. The Brewster airplanes simply lacked the strength for prolonged service at sea. On New Year’s eve, Task Force 11 headed in for what it hoped was action at last, as radio intelligence pointed to enemy warships supposed lurking off Johnston Island. Brown closed in for the kill, but soon learned it was another false alarm. Once again Ramsey’s squadron endured a landing mishap. At this rate the F2As would not last long enough to fight! (An outcome that would have been better for everyone.) The first two days of 1942 Brown steamed back toward Oahu. On 3 January, the whole group took up residence at MCAS Ewa, where Fighting Two reported to the Army’s 7th Pursuit Command for temporary duty on air defense. The Lexington herself would be in the navy yard for several days, while concerned specialists tried to remedy an electrical ground in one of her four main rotors. If they could not effect repairs, she would have to limp to Bremerton.

Task Force 14’s turn in port came next. On the trip back from Wake Fletcher had also encountered turbulent seas. Because of the date line, the ships enjoyed two Christmas Days, and during the second, the Saratoga was able to send VMF-221’s fourteen F2A Buffaloes to Midway. Spared combat at Wake, VMF-221’s leathernecks would bear the brunt of the June 1942 Japanese air assault on Midway. The afternoon of 27 December afforded Thach the long-awaited opportunity for gunnery exercises, and he took all twelve F4Fs aloft for runs on towed sleeves. Two days later, the Saratoga Air Group flew to NAS Kaneohe Bay, and the ships docked at Pearl.

During their brief time ashore, Fighting Three caught up with the mail and finally had a chance to relax. The squadron sold off four F4F-3As (including three VF-6 airplanes that VF-3 did not have a chance to fly) and drew one F4F-3 in return. Also available were two F2A Buffaloes on loan from Fighting Two. In light of VF-3’s previous experience with F2A-2s, these Brewsters were no problem to fly. However, on 30 December, Thach still only counted fourteen fighters (twelve F4Fs and two F2As). Little yet could be done to alleviate the near-crippling shortage of fighters with the fleet.

On 30 December, Task Force 14 changed admirals. Fletcher left his flagship Astoria for a new carrier task force assembling at San Diego. Taking his place was another nonaviator, Rear Admiral Herbert Fairfax Leary, Commander, Cruisers, Battle Force. He broke his two-star flag on board the Saratoga. Rear Admiral Fitch reluctantly went ashore as Halsey’s administrative representative for Aircraft, Battle Force. Among the urgent items he handled were organization, supply, and materiel for all of the carrier squadrons shore-based on Oahu. He also saw to the organization of special carrier air service units at the various naval air stations in the Hawaiian Islands. Fitch worked diligently and successfully to bring the carrier air groups to full operating strength, but he would be sorely missed at sea.

Leary’s Task Force 14 with the Saratoga (fourteen fighters, thirty-seven dive bombers, and thirteen torpedo planes), two heavy cruisers, and six destroyers sailed on 31 December to patrol in the Midway area. The first few days were routine, and Fighting Three worked in some excellent training on 2 January. The next day an AlNav (All-Navy) despatch from the Bureau of Navigation brought news that nearly everyone had been promoted one rank. Thach and Lovelace became lieutenant commanders, most jaygees stepped up to senior grade, and ensigns with long service added a half-stripe as lieutenants (junior grade). Quite a scramble ensued for the proper insignia and an opportunity to be sworn in by the captain. The promotions were Navy-wide and provided a more realistic rank, given responsibilities of the new war. They certainly were welcome in all of the fighting squadrons. For Thach, celebrations were dampened by illness. On 4 January he went on the sick list, and Lovelace led Fighting Three for the rest of the cruise.

Taking his turn in the Oahu revolving door was Bill Halsey, returning on 31 December after being a distant spectator to the drama at Wake. His mission of covering Midway proceeded without a hitch. Just before reaching Oahu, the Enteprise sent her air group to Ewa. Wade McClusky took eight F4Fs there, leaving four under Roger Mehle to patrol over the carrier on her approach to Pearl. Ens. John C. Kelley, piloting one of the VF-6 F4Fs, made a normal takeoff run up deck until he lifted off. Then the Wildcat suddenly skittered left, dropped its left wing radically, and stalled. Kelley narrow missed the deck edge, while he spiraled into the sea. Despite smashing his head on the gunsight mount, Jack Kelley scrambled free of his sinking plane to be picked up by the plane guard destroyer. Fighting Six stayed briefly at Ewa and commiserated with the marines over bottles of beer about the fate of Wake. The same afternoon, they flew on to Ford Island, where there was no New Year’s liberty for them. The uninterrupted sleep they enjoyed was almost worth missing the parties. For the next few days the squadron rested ashore. On 2 January they took delivery of four F4F-3As courtesy of Thach (three were originally VF-6 planes) and turned in the orphan F2A Buffalo. Fighting Six now boasted seventeen F4F Wildcats (fourteen F4F-3As and three F4F-3s).

The morning of 3 January, Task Force 8 departed on a make-work cruise north of Oahu for some gunnery training, to cover an important convoy coming in from the States, and to have only one carrier task force in port at a time. McClusky took fifteen F4Fs out to the Enterprise and left two ashore for the five new pilots, Presley, Hodson, Grimmell, Criswell, and Holt, to use in field carrier landing practice. The next day, Halsey’s ships carried out practice of their own, antiaircraft gunnery exercises. Flying inner air patrol (and carefully keeping well clear), the VF-6 pilots were not impressed: “If those guns ever do go into action they will probably bring down as many friends as foes.”4 Rough seas curtailed training the following two days. On 7 January, the Enterprise flew off her aircraft before coming into port. Fighting Six first flew to NAS Kaneohe, then hopped over to base at Ewa with their marine buddies. They landed in the rain, which was okay until the marines decided to respot the fighters. The VF-6 pilots had to brave the weather and taxi their Wildcats to new parking areas.

Again because one carrier was coming into Pearl, another had to leave. Her turboelectric drive now functioning properly, the Lexington sailed on 7 January, now as flagship of Task Force 11 because Brown had moved over from the heavy cruiser Indianapolis. CinCPac had planned originally to use Task Force 11 against enemy bases at Wotje and Maloelap atolls in the Marshalls in connection with other operations being planned, but then changed his mind; Brown’s orders were to conduct the usual patrol toward Johnston. Leary’s Task Force 14 operated northwest of that area. Ramsey had seventeen F2As with him on board the Lexington, but only fifteen were flyable. Brown set a southwest course toward Johnston Island.

The enemy was closer at hand than many realized. On 6 January while Task Force 14 started back to the southeast from Midway, a Saratoga dive bomber on search spotted an enemy submarine traveling eastward on the surface. The SBD attacked, but dropped an unarmed 500-pounder on the I-boat as it crash-dived. The next day the submarine still lurked nearby. Another Saratoga SBD pilot saw her bucking heavy seas 47 miles southeast of the task force and attacked, but again the bomb was not armed! Both days Fighting Three conducted tests and deck handling practice with the folding wing XF4F-4. On 8 and 9 January, the seas grew so tumultuous that flying was canceled. Waves washed over the Sara’s bows, and seawater ran into the forward elevator well. Central Pacific seas in winter did not make for pleasurable sailing! Leary continued southeasterly at a slow pace, bound for a rendezvous with Halsey’s Task Force 8 set up by CinCPac to allow the Saratoga to exchange aircraft with the Enterprise. As part of this, Thach was to hand over his F4F-3s to McClusky in return for VF-6’s less desirable F4F-3As.

Task Force 11 with the Lexington, heading southwest from Pearl toward Johnston Island, next became involved with the I-boats. Around 0630 on 9 January, lookouts on I-18 spotted Brown’s ships about 300 miles northeast of Johnston. The skipper, Cdr. Otani Kiyonori, radioed to Sixth Fleet headquarters the position, course, and speed of the Lexington-class carrier and cruiser he had found. That alerted the submarine command to the presence of an American carrier force operating around Johnston, and it pulled several I-boats from patrols off the Hawaiian Islands in order to pursue Otani’s contact.5

On 10 January, unaware she had been sighted the previous day, the Lexington launched a routine search of twelve SBDs to proceed 300 miles ahead of the task force, while four VF-2 F2As covered the remainder of the circle with 50-mile precautionary patrols astern. At 1020, Fighting Two got its first look at the enemy.6 Lieut. (jg) Fred Simpson and Doyle C. Barnes, AMM1c, caught sight of a Japanese submarine running surfaced about 60 miles south of the task force. The I-boat’s lookouts were on the ball, and the skipper crash-dived before the two F2As could get close. Simpson hightailed it back to the Lexington, at 1057 dropping a beanbag message container onto the flight deck. The note inside detailed the submarine’s course and speed (270 degrees, 18 knots) and position, which when plotted worked out to roughly 100 miles west of Johnston.

The Lexington recovered the morning search, and at 1230 sent a similar mission with SBDs and F2As. As an added bonus, Sherman also despatched two pairs of TBD Devastators from Torpedo Two. Each carried two 325-lb. depth charges. They did not have long to wait. Flying their 50-mile search, Lieut. (jg) Clark Rinehart and Charles E. Brewer, RM1c, from Fighting Two eyeballed the same I-boat, brazenly cruising on the surface now 80 miles south of Task Force 11. So as not to spook the enemy into submerging, Rinehart cleverly pulled back up sun, and at 1325 reported his position to the ship. The Lexington vectored to the scene two TBDs, flown by Ens. Norman A. Sterrie and Harley E. Talkington, AOM2c.

Meanwhile, Rinehart held back until he saw the two Devastators in position; then he led Brewer in a strafing run. Sterrie and Talkington approached at 2,000 feet, and at 1341 dived in. The Japanese finally saw them coming, and the I-boat began to plow under the waves. Sterrie salvoed his two depth charges just astern of the sub, but his wingman’s ash cans failed to release. Attacking from the other side of the sub, the two VF-2 pilots opened fire with their Brownings at 3,000 feet, holding down the triggers as they charged in. Rinehart later described the action:

We could see our tracers bouncing off his deck as he went down, so I know bullets were going into him. And don’t let anyone tell you those .50-calibers won’t tear a hole in anything they hit.7

The two kept shooting until they had to pull out. Brewer had an exceptionally fine view of the proceedings, as he recovered at 100 feet. The two F2As had expended 650 rounds in the run. Talkington meanwhile had swung around, and this time he put his two depth charges 50 to 75 yards ahead of the I-boat as she finally slithered under the water. From his low-level vantage point, Brewer was certain these near misses “jerked sub abruptly to the right”8 and inflicted some damage. Afterward a small oil slick stained the water.

Joined by the other two TBDs, the four attackers carefully searched the area for another hour, but spotted no further trace of the submarine. Returning to the ship, Rinehart jotted down a short summary of the attack and put it inside a message container. His manner of delivery caused quite a stir on board the Lexington:

As he swooped across the flight deck, at bridge level, he had to turn his plane on its side to avoid nicking the stack with a wing tip. Just hanging on his prop, he slid past the bridge, where everyone was taking cover, thinking he was going to crash, and neatly deposited his bean bag at the feet of Admiral Brown.9

For the past month, the Lexington’s pilots had taken some verbal abuse for the accuracy of their message drops, and Rinehart showed how he thought it should be done.

Brown detached the destroyers Phelps and Monaghan with prospects of finishing off a crippled submarine, but they found no trace of the enemy. The I-boat was marked down only as “damaged.” That evening in the wardroom, Ramsey, with a smile he could not hide, “reprimanded” Rinehart for his show-off message drop, then warmly commended him for his presence of mind in not attacking immediately. It was far better that he waited and summoned those who could strike the enemy a more telling blow. Japanese records do not mention the incident, but it appears from examining their official history that the submarine I-19 (carrying Captain Imaizumi Kijirō, commander of 2nd Submarine Division) is by far the likeliest candidate for the attack. She arrived on 15 January at Kwajalein from a patrol off the West Coast.10

By 10 January, Task Force 14 had been out for a dozen days, mainly a boring cruise marking time northwest of Oahu. Leary often zigzagged slowly at 7 to 12 knots to conserve fuel. Usually seas were high and skies overcast, permitting the fighters little opportunity to fly. The afternoon of 10 January, as Task Force 14 continued on a southeasterly course toward the rendezvous with Halsey, there was a remarkable deck crash. While one VT-3 TBD made its landing approach, high waves sent the Saratoga pitching steeply. Her stern rose abruptly, and the LSO tried to wave off the TBD, but it kept coming. Then, with a horrible rending noise, the Devastator struck the edge of the ramp and tore in half. Its engine and portions of the cockpit with the pilot, Ens. Earle C. Gillen, still strapped in his seat, clattered onto the flight deck. The rest of the shattered aircraft fell into the sea astern, killing both passengers. Dazed, Gillen unstrapped his seat belt and unsteadily tried to rise. He could not stand—the impact had broken his leg.

The next day, 11 January, seas were a little less turbulent, but the giant Saratoga still bounced playfully amid the “long, big swells.”11 Ready to take off on morning CAP, Lovelace waited for the signal to go, but Captain Douglas canceled all flights. Three long blasts from the stack whistle announced his decision. Pilots on deck cut engines. Again the Sara shipped water over her massive bow. Fighting Three spent another quiet day on routine squadron duties. At 1915, while the pilots enjoyed dinner in the wardroom, a “terrific explosion”12 shattered the calm. The Sara first heeled violently to starboard, then fell back to port. A submarine torpedo had slammed into port side amidships, torn into three firerooms, and killed six firemen. At the sound of general quarters, the VF-3 pilots ran for their ready room. The Saratoga took on a list to port, but damage control soon had the situation under control. When she was hit, the Saratoga was 420 miles southwest of Pearl and holding a southeasterly course. Her assailant was I-6, one of the boats that had chased the Enterprise in December. Cdr. Inaba, her skipper, radioed exultantly that he had sunk a Lexington-class ship in position bearing 060 degrees, 270 miles from Johnston. Although far from gone, the Saratoga was in a bad way. Leary canceled the rendezvous with Halsey and set course for Pearl.

The morning of the twelfth Fighting Three joined the crowd assembled on deck to survey the damage. Fuel oil from torpedo-shattered oil bunkers had spattered aircraft parked aft on the flight deck. Metal fragments lay all over the deck courtesy of the large gash riven into the carrier’s tender flank. The Sara could still make 16 knots, and that morning she launched SBDs on search. One of them attacked an I-boat on the surface and drove it down with a 500-lb. bomb (this time armed). To follow up the contact, she despatched seven more SBDs on a search and destroy mission. They ended up harassing an oil slick and flew on to Pearl. The Sara herself experienced some scary moments after 1230, when water in contaminated oil tanks caused a loss of fuel suction. The carrier drifted without power for a short time before the engineers could correct the problem. The Saratoga would be laid up for a long time; the question was whether she could be repaired at Pearl.

The Lexington also experienced a far from tranquil 11 January. Task Force 11 steaming northwest of Johnston weathered heavy swells from the northwest but encountered little wind. This made for difficult flying conditions. The morning search went all right, but poor conditions slowed the takeoffs for the afternoon mission. At 1250, a bad rain squall interrupted the launch after only four fighters and six dive bombers had gotten away. An hour later two “freak” waves broke over the Lexington’s bow, washed down the flight deck, and ran into the forward elevator well. A short circuit rendered both flight deck elevators inoperable. Sherman canceled further flight operations, and not until 1630 was the Lex able to recover the abortive afternoon search.

At 0600 on 13 January, Lovelace led most of the Saratoga Air Group to NAS Pearl Harbor, as the wounded carrier made ready to enter port. Thach checked into the naval hospital for treatment, while Fighting Three began shifting over to Ewa. Word had it that they would be there for a long time. In the navy yard, ship’s company and workmen labored furiously to unload the Sara prior to drydocking her. The next day, VF-3 baggage headed out to Ewa. Lovelace sold back to Fighting Two the pair of F2As borrowed two weeks earlier. A new pilot fresh from operational training, Ens. Newton H. Mason, reported for duty. Lovelace himself finally made it out to Ewa on 15 January. There workmen were rebuilding the marine air station after massive damage incurred on 7 December. Conditions were still spartan, “but the food is OK and the sleeping is good,”13 commented Lovelace

Task Force 11 with the Lexington returned on 16 January to Pearl. Nimitz brought Brown back in order to regroup and offer support for the reinforcement of Samoa and subsequent raids on the Marshalls that were planned. Ramsey’s VF-2 along with the rest of the Lexington group ended up at Kaneohe. There, two NAPs, Harry Carmody, AMM1c, and George White, AMM2c, left for other assignments. On 17 January, CinCPac decided to send the Saratoga back to the West Coast for repairs. One fighting squadron would soon be short a flight deck!

Mid-January at least saw the first arrival of replacement fighters for the fleet. Around 14 January a transport brought in seven disassembled F4F-3s and F4F-3As from the West Coast. Due in a few days were ten more F4F-3As from VMF-111 and 121 based at NAS San Diego. These airplanes would allow Fighting Three to operate at full strength of eighteen fighters and also permit Fighting Two to exchange its Brewster F2As for Grummans. The fighter strength in the Pacific Fleet as of 15 January 1942 is shown in the table.14

THE SAMOAN OPERATION—THE YORKTOWN TO THE PACIFIC

When Nimitz took over as CinCPac, he found his Pacific Fleet already committed to one major undertaking for January 1942, the reinforcement of the American garrison at Samoa. As early as 14 December, Admiral Stark had arranged for a special convoy to assemble at San Diego. It would transport the 2nd Marine Brigade to Samoa. Departure was to be in early January.

For direct escort of the Samoa convoy, Stark earmarked the aircraft carrier Yorktown (CV-5), then at the main Atlantic Fleet base at Norfolk, Virginia. Commissioned in 1937 as the Navy’s first truly modern flattop, the Yorktown in 1941 had only been on loan to Admiral King’s Atlantic Fleet. She had previously served in the Pacific as Bill Halsey’s flagship when he first commanded Aircraft, Battle Force and concurrently Carrier Division Two. He along with the rest of the fleet had been sad to see her hasty departure in April 1941 for the Atlantic. The Yorktown with three battleships and numerous other vessels from the Pacific Fleet acted to beef up the naval forces that President Roosevelt was arraying to confront more effectively Adolf Hitler’s Kriegsmarine in the North Atlantic. Her first task upon arriving on the East Coast was to dock at the Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, there to prepare for extended operations in the Atlantic. Leaving the Yorktown Air Group for temporary duty ashore was her fighting squadron, Lt. Cdr. Wallace W. Beakley’s Fighting Five (VF-5). Beakley’s troops still operated Grumman F3F-3 biplanes and were scheduled to convert to Grumman F4F-3A Wildcats. Taking VF-5’s place for what was supposed to be a limited time was Fighting Squadron Forty-two (VF-42), extracted from the Ranger Air Group. As it happened, Fighting Five never did return to the Yorktown, as Fighting Forty-two took her to war and her final battles.

Formed in July 1928 as Scouting Squadron One (VS-1B),1 the air unit that later became Fighting Forty-two was another of the old Langley squadrons. In 1929, VS-1B was supposed to reequip eventually with Keystone amphibian floatplanes, complete with landing gear and tail hooks. Consequently the pilots adopted as their insignia a duck sporting pontoons as footgear, but the amphibians never arrived. With the commissioning of the carrier Ranger (CV-4), Scouting One transferred from the Langley and took up residence on board. During the 1 July 1937 reorganization, the squadron’s designation changed from VS-1B to VS-41 (Scouting Squadron Forty-one), identifying it as one of the Ranger’s two scouting squadrons (she did not have a bombing squadron). In early 1941, the Navy decided to form two fighting squadrons for the Ranger Air Group as well as two for the new carrier Wasp (CV-7). At the time, the Navy was de-emphasizing torpedo units, so that the air groups aboard those two carriers would comprise two fighting and two scouting squadrons. In peacetime at any rate, one fighting squadron at a time would serve on board, while the other stayed ashore to train pilots or was available to go out on board another carrier if need be. The Ranger’s regular fighting squadron, Fighting Four (VF-4, the “Red Rippers”), became Fighting Forty-one (VF-41). On 15 March, Scouting Forty-one changed its designation and type to Fighting Squadron Forty-two (VF-42). The pilots were delighted to trade their old, slow, and lumbering Vought SBU-1 biplane scout bombers for sleek, new Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats fresh from the Grumman factory on Long Island. The squadron spent the spring of 1941 getting acquainted with their new role and aircraft.

In June 1941, VF-42’s executive officer, Lt. Cdr. Oscar Pederson, fleeted up to squadron command when the old skipper, Lt. Cdr. Thomas B. Williamson, finished his tour of duty. Tall, easygoing, and genial, “Pete” Pederson had graduated in 1926 from the Naval Academy. Earning his wings in 1930, he saw service in flying boats, then carrier duty (1935–36) in Scouting Four (VS-4B) on board the Langley. In June 1940, he reported to Scouting Forty-one, working his way up to commanding officer the next year. He had no previous operational service in fighters, but he was an experienced naval aviator and ready to assimilate fighter doctrine. His new executive officer, Lieut. Charles R. Fenton, was considerably more seasoned in fighters, and proved invaluable during the squadron’s transition.

The Yorktown, with VF-42 now part of her air group, set sail on 28 June 1941 from Norfolk on what would be the first of four “Neutrality Patrols” in the North Atlantic. The initial pair of cruises were uneventful, but the third, in September, took the Yorktown into the fog-bound, rainy waters off Newfoundland, and in October and November the carrier helped escort convoys as close as 700 miles from German-occupied Brest, France. She returned on 2 December to Norfolk via Halifax and Portland, Maine. The air group at this juncture was promised extended duty ashore, while the ship herself was to undergo vital refit and upkeep after her strenuous sea duty. The fighter pilots in particular welcomed the chance for shore duty because their flying (tactics and gunnery in particular) had been curtailed while the Yorktown was on active operations. The need for strict radio silence, for example, prevented much training on fighter direction. The pilots were all keen to learn as much as they could about modern fighter operations. That fall they were briefed by Lt. Cdr. William E. G. Taylor, USNR, a highly experienced naval aviator who had served for a time in a Royal Navy carrier fighter squadron and as commander of the RAF’s famed “Eagle Squadron.”

On the fateful day of 7 December 1941, the Yorktown was berthed at Norfolk, while Fighting Forty-two with sixteen pilots present (another was ill) and eighteen Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats in commission operated out of NAS Norfolk’s East Field.

The following pilots were with the squadron:

Lt. Cdr. Oscar Pederson |

USN |

USNA 1926 |

Lieut. Charles R. Fenton |

USN |

USNA 1929 |

Lieut. (jg) Vincent F. McCormack |

USN |

USNA 1937 |

Lieut. (jg) William N. Leonard |

USN |

USNA 1938 |

Lieut. (jg) Richard G. Crommelin |

USN |

USNA 1938 |

Ens. Roy M. Plott |

USN |

|

Ens. Arthur J. Brassfield |

USN |

|

Ens. Brainard T. Macomber |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. Elbert Scott McCuskey |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. William S. Woollen |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. Leslie L. B. Knox |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. William W. Barnes, Jr. |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. Walter A. Haas |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. Edgar R. Bassett |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. Richard L. Wright |

A-V(N) |

|

Ens. John P. Adams |

A-V(N) |

|

With the startling news of the Japanese attack, squadron personnel began packing to board the Yorktown. Although the carrier remained far from battleworthy because of the need for a refit, there were furious preparations to get under way. Naval authorities feared an attack by the Germans against the Yorktown and some British carriers undergoing repairs at Norfolk. Early the next morning, VF-42 laboriously taxied its aircraft down to the dock where they were hoisted on board. Three new pilots, Ens. Edward Duran Mattson, USN (a 1939 Annapolis graduate), Ens. John D. Baker, A-V(N), and Ens. Harry B. Gibbs, A-V(N) reported for duty. Mercifully the powers that be canceled the Yorktown’s immediate sortie, and the carrier repaired to drydock for much-needed attention to the underwater portions of her hull.

Fighting Forty-two returned to East Field for a week of hard work to ready their fighters for combat. Squadron mechanics installed self-sealing fuel tanks and fitted pilot armor in each Grumman, both time-consuming processes. Pederson agitated hard for permission to remove the bomb racks from his Grummans, and Captain Elliott C. Buckmaster of the Yorktown acquiesced. Any savings of weight and drag were profitable in terms of performance. Unfortunately, the squadron could not obtain any of the innovative reflector gunsights, nor could the clumsy old sighting-tube telescopic gunsights be used with the bulletproof windshields intended for the F4Fs. This was a serious matter because Fighting Five still was not ready to resume its place on board the Yorktown. Pederson’s troops remained with the ship. In light of VF-42’s conspicuous opportunities for early combat and the fine record her people amassed, their colleagues in Fighting Five never quite forgave them for taking VF-5’s own ship to war.

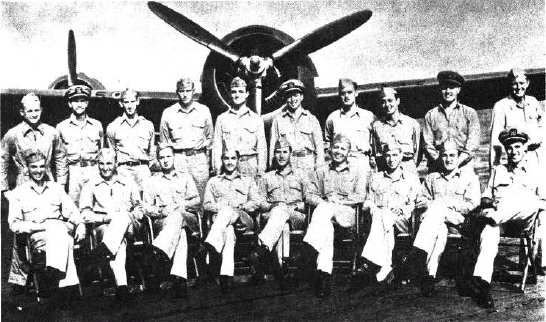

VF-42, 6 Feb. 1942, l to r top row: Mattson, Wright, Gibbs, Barnes, Baker, McCuskey, Crommelin, Adams, Bassett, Haas; seated: Macomber, Brassfield, Plott, Leonard, Fenton, Pederson, McCormack, Woollen, Knox. (RADM William N. Leonard, USN.)

Art Brassfield, VF-42’s able engineer officer, 13 Nov. 1941. Note old telescopic gunsight on F4F-3. (NA 80-G-64709.)

While the Yorktowners labored so industriously to prepare for war, the high command worked out the details of her first mission. There was no doubt she was going back to the Pacific. As related above, the Yorktown was tapped to escort the Samoa reinforcement convoy departing the West Coast in January. Buckmaster received orders to proceed to San Diego via the Panama Canal. The Yorktown and her escorts sailed on 16 December from Norfolk, well-loaded with aircraft and other vital gear for the Pacific. On 21 December, Fighting Forty-two flew thirteen Grummans to France Field, Canal Zone, to provide combat air patrol for the flattop’s passage through the canal. Lieut. (jg) William N. Leonard’s F4F had the misfortune to blow a tire. He was most anxious not to be left behind, and the flight officer, Lieut. (jg) Vincent F. McCormack, managed to get new tires installed just before the carrier cleared Gatun Lock. The next day the Yorktown steamed northwestward into the Pacific. The VF-42 contingent at France Field took off, buzzed the canal, then hurried after their carrier now drawing away from Panama.

On 30 December, the little Yorktown task force approached the California coast. Fighting Forty-two along with the rest of Lt. Cdr. Curtis S. Smiley’s Yorktown Air Group flew to North Island to land at NAS San Diego. Later that day the Yorktown herself anchored safely in San Diego harbor. Assembled there were the various vessels assigned to convoy troops to Samoa: three ocean liners doubling as transports, an ammunition ship, an ex-collier, and a fleet oiler. On New Year’s Day, Rear Admiral Fletcher and his staff boarded the Yorktown. They had flown in from Pearl to form a new Task Force 17 with the Yorktown as flagship. It was to be an exciting and memorable association. Fighting Forty-two’s New Year’s morning was not so cheerful. The Army had turned the lot of them out at 0600 for alert because of a possible, enemy air attack. None materialized.

Pederson’s squadron spent a hectic week at NAS San Diego making final arrangements before departing for combat. Bill Leonard and assistant, Ens. Walter A. Haas, with “intense bird dogging” ran down the necessary supplies and gear, which included: “spares for consumables, the latest kits for airframe and engine modifications, gunsights and electrical wiring and controls.”2 Leonard especially sought N2AN illuminated reflector gunsights and turned some up at San Diego. Squadron armorers had to rearrange instrument panels to fit them in and jury-rig mounts to hold the sights. These would prove hazardous to foreheads in the event of ditching, but at least VF-42 had something they could use to shoot at the enemy. Meanwhile the Yorktown began loading thirty-two additional aircraft as cargo to be transported out to Pearl Harbor. These included twenty F4F-3s and F4F-3As taken from VMF-111 and VMF-121, urgently needed by the fleet. The Yorktown’s own air group had the following organization:3

With a utility group of three planes and twenty-nine planes (twenty F4Fs and nine SBDs) as cargo, the Yorktown would have 101 aircraft for the next cruise.

The afternoon of 6 January, Task Force 17 stood out from San Diego. Fletcher’s force comprised the Yorktown, the heavy cruiser Louisville, the light cruiser St. Louis, four destroyers, a fleet oiler, and the convoy itself of five vessels. The air group was snuggly embarked, having been earlier hoisted on board the carrier. Task Force 17 was South Pacific–bound. As the Yorktown passed Point Loma, the carrier went to general quarters and:

. . . launched just about the whole VF squadron. We were told this is the way it would be—Japs just over the horizon. We got off smartly and Fletcher was pleased at our sparkiness and willingness to play any games ordained.4

Pederson started the voyage with eighteen Wildcats on strength, but soon he would not have nearly so many. The troubles began on 7 January. That morning VF-42 flew two morning CAPs and checked out a number of contacts. Landing from one of the patrols, Ens. Edgar R. Bassett touched down all right, but found himself enmeshed in the barrier. The arresting wire had snapped, injuring three men on deck. The next morning there was an amusing incident. Well before dawn, meteorologists on board the Yorktown released a weather balloon, which lookouts on board one of the cruisers misidentified as a signal for an emergency turn. The ship, and perforce the rest of the task force, turned left 45 degrees. Fletcher acted swiftly to put his ships back on course.

For VF-42 the morning CAP went smoothly, but a mishap occurred the afternoon of 8 January. At 1415, six fighters began taking off for combat air patrol. One of them, 42-F-1, flown by Ens. William S. Woollen, started down the deck as the Yorktown, beset by deep swells, began rolling to starboard. Almost immediately, Woollen’s right wing dropped, throwing the Grumman into a violent twist to port. He added throttle, but could not regain control. After only 200 feet of run, the Grumman shot out over the portsidc of the flight deck and settled into the water, hitting 300 yards off the port bow. The Yorktown maneuvered to avoid the sinking aircraft, and soon the destroyer Russell had Woollen on board. A VF-42 trouble board later blamed the incident on the carrier’s roll combined with torque from the Wildcat’s engine.5 Fighting Forty-two pilots carefully thought over the question of launch and asked for permission to experiment with takeoffs when the carrier placed the wind 10 degrees off the starboard bow. After such a launch, the fighter pilot would turn left to clear his slipstream from the flight deck rather than to the right as was standard practice. The Yorktowners later declared this method to be much superior to the old of heading directly into the wind and swinging to the right after takeoff. The new procedure permitted shorter intervals between fighters during launch.

The next few days, VF-42 flew routine combat/inner air patrols. The morning of 12 January and again that afternoon, the pilots on CAP simulated coordinated strafing runs on the destroyers. One pilot, however, did not complete the afternoon flight or even get well into it. Walt Haas in 42-F-3 ran through a normal takeoff until, under the new procedure, he turned left to clear his slipstream from the deck. Haas happened to look over his right shoulder, but forgot to watch his speed and climbed slightly. His unforgiving Grumman stalled, then nosed down in an uncontrollable spiral toward the water. Just as the left wing slapped the sea, Haas threw his upper body to the right side of the cockpit in an effort to keep his head away from the wicked gunsight mount. He scrambled out of the sinking plane and was soon on board the destroyer Walke. Fortunately Haas was not hurt badly, but he along with the rest of the squadron began to experience a great hankering for shoulder straps to restrain head and body motions from pitching them into the gunsight mount during a crash.6

Two days later, the Walke took on board another uninvited guest. Task Force 17 and its charges sailed right down on the equator, and it was hot. At 0730 on 14 January, the Yorktown began launching six fighters for routine CAP and more mock strafing runs on destroyers. In the midpoint of his takeoff run, Ens. Richard L. Wright in 42-F-14 noticed he just was not getting enough airspeed. It was too late to stop—his Grumman went out over the bow and immediately dropped toward the water. Wright carefully turned left to clear the carrier, then ditched 200 yards ahead. Although the Walke rescued him in less than ten minutes, VF-42 was now down to fifteen operational planes. For Wright’s mishap there was no ready explanation; perhaps the electrical propellor pitch control was at fault.7 That day, the task force crossed the equator, but dispensed with the high jinx common in other vessels. The VF-42 pilots were concerned with the mounting operational losses, and certainly they did not pine for the frivolities because most were not yet Shellbacks and were vulnerable to initiation.

Steaming southward from Pearl Harbor to join Fletcher off Samoa was Halsey’s Task Force 8 with the Enterprise. On New Year’s Day, CinCPac had decided to combine the two task forces to execute some sort of offensive action against enemy island bases. Prodding him the next day was an order from King, the new CominCh, calling for “some aggressive action for effect on general morale.”8 Given the circumstances, only Bill Halsey would be available. On 7 January he had returned to port. The next day Nimitz ordered him to proceed to Samoa, combine Task Force 17 with his own Task Force 8, and orchestrate simultaneous raids on the Marshalls and Gilberts, the attacks to take place the first week of February. Fighting Six along with the rest of the Enterprise Air Group spent a few days ashore on “unavailable status,” allowing for a rest of sorts. The stay was noteworthy mainly for 10 January, when the squadron finally managed to accumulate eighteen F4F Wildcats—the first time VF-6 had operated at full strength since peacetime.

The Enterprise with an escort of three heavy cruisers and seven destroyers set sail the morning of 11 January. After lunch, Wade McClusky gathered eighteen pilots from Fighting Six and led them out to the ship. Rookie pilots Dave Criswell and Wayne Presley made their first carrier landings this flight, a reward for hours of field carrier landing practice. Task Force 8 at first headed due west—the destination as yet a secret to the pilots. The AirBatFor staff alerted Fighting Six to prepare for the eleven-plane “swap” with Fighting Three on board the Saratoga. McClusky’s troops were to exchange most of their F4F-3As for F4F-3s, some of them already fitted with pilot armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, as yet unavailable to Fighting Six. The next day, McClusky learned the trade was off. The Saratoga had taken a fish and now limped back to Pearl. The pilots were a little dismayed at not getting the better planes, since it now appeared they would soon see some action. Halsey had changed course to the southwest and informed his people that they would head for Samoa to escort a convoy, then, in the words of VF-6, “raise a little hell up in the Gilberts or Marshalls.”9

By 14 January, Halsey’s ships were deep in the lower latitudes and uncomfortably hot weather. Fighting Six was in hot water with the air department as well. Norm Hodson on an inner air patrol had flown to the wrong sector, while Ed Bayers and Wayne Presley got lost in a rain squall. The Enterprise had to break radio silence to guide them back to the ship. Intelligence placed a number of enemy flattops lurking in the Marshalls, so the missing self-sealing tanks and armor looked dearer than ever. The next day as the task force neared the equator, the weather was even more torrid: “Fighter pilots flying the noon CAP with open cockpits and 150 knots of wind to cool them returned parched and dehydrated, for the wind itself was like a volcano’s breath.”10 The feud with the air department persisted, as VF-6 grumbled, “They changed their minds five different times about what we’d do in what planes this date.”11 The task force crossed the equator without any particular ceremony, probably a good idea considering the mood most were in.

The sixteenth, another scorcher, was an even worse day for the task force. An SBD crashed on landing and killed the chief petty officer manning the arresting gear, while a TBD from Torpedo Six ditched, its crew missing. (They sailed an eventual 750 miles in a rubber raft and fetched up on the beach of Puka Puka.) On board ships in the task force, two sailors also died of accidental causes. The next day another SBD ditched from lack of fuel. There was no flying for Fighting Six while the Enterprise refueled from a fleet oiler.

The actual Samoa reinforcement went without a hitch. Both task forces converged on the lush island group. Fletcher on the night of 19 January released his fast transports for the run to Tutuila Island, the slower vessels following the next day. While the convoy disembarked troops and supplies, the carriers maneuvered off Samoa, occasionally catching tantalizing glimpses of the green tropical isles during breaks in the usually squally weather they encountered. Far to the west four Japanese carriers savagely pounded Australian defenses at Rabaul on New Britain, presaging a new Japanese thrust into the Southwest Pacific. Meanwhile, Task Forces 8 and 17 marked time accomplishing their mission of covering Samoa. Then there would be time to pay the Japanese a visit.

While southern waters beckoned Halsey and Fletcher, Wilson Brown’s Task Force 11 suffered through a short but frustrating cruise in the Central Pacific. The morning of 19 January after three days in port, the Lexington along with the rest of Task Force 11 (three heavy cruisers and nine destroyers) sailed from Pearl Harbor to conduct a patrol in the waters northeast of Christmas Island. Nimitz desired that Brown support the other two carrier task forces when, after the Samoan operation, they made the first counterstrikes on Japanese island bases. Late that afternoon, the Lexington Air Group flew out to the ship. Lt. Cdr. Ramsey had sixteen F2A Buffaloes on strength with Fighting Two. While on shore he had turned in two unserviceable Brewsters and from Fighting Three received the two he had lent them. Task Force 11 took up a southerly heading. For the next few days, flight schedules called for gunnery training flights interspersed with short searches and intermediate air patrols.

In Washington, CominCh monitored intelligence reports placing the enemy carrier striking force deep in the Southwest Pacific. The time looked ripe to launch a diversionary carrier strike in the Central Pacific. On 20 January, King suggested a carrier raid on Wake. The next day Nimitz chose Brown’s Task Force 11 to deliver the surprise strike on Wake and obtain some revenge for the capture of the island. Fuel, however, would be a problem as it was during the abortive relief expedition the previous month. Brown had no oiler with him, so Nimitz arranged to send his one available fleet oiler, the venerable Neches, to rendezvous before the strike.

Brown received his orders the afternoon of 21 January. He was to refuel on 27 January from the Neches, then raid Wake with aircraft and follow with a ship bombardment if the situation permitted. To escort the old girl to the rendezvous, Brown detached the destroyer Jarvis and followed himself at a more economical pace. Everyone on board the ships looked forward to the opportunity of smashing the Japanese at Wake. Unfortunately, during the predawn hours of 23 January the Imperial submarine I-72 found and sank the as yet unescorted Neches 135 miles southwest of Oahu. Brown learned of the loss of his oiler later that morning. Without her fuel, there was no way the task force could steam to Wake, fight, and return. Nimitz recalled Task Force 11 to Pearl. Disgusted, Brown at 1900 changed course northeastward for Oahu. Someone else would have to make the first Pacific Fleet counterattack against the Japanese.