![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

While the exhausted pilots slept, or tried to, an equally tired Spruance thought hard in the early hours of 5 June about how to avoid a possible night counterattack by the enemy and yet position his battered and bruised carrier air groups where they could do some good after daybreak. He withdrew Task Force 16 eastward until 0200, then reversed course westward to approach the Japanese once again. From submarine alerts, he learned of an enemy force bearing down on Midway, and at 0420 came around to the southwest to move into direct support range of the island. The ships glided into a band of bad weather; fog and rain greatly reduced visibility and threatened air operations if those conditions persisted after sunrise. As on the previous day, Spruance relied on Midway-based planes to conduct searches and pinpoint enemy ships. Too few SBDs remained to conduct both searches and follow-up air strikes. Carefully he husbanded what dive bombers he had (his torpedo squadrons had virtually been destroyed), to unleash them should Japanese carriers turn up. The American carrier planes had sunk or maimed four enemy flattops, Spruance knew, but it was within the realm of possibility the Japanese might have a tough old bird like the Yorktown out there and back in action. Perhaps a fifth enemy carrier also lurked nearby, something that earlier CinCPac intelligence estimates had warned about.

Dawn found Task Force 16 socked in, so Spruance depended more than ever on Midway’s faithful patrol squadrons. At 0630, a PBY radioed a position report for two Japanese “battleships” bearing 264 degrees, distance 125 miles from Midway. They lay within range of his SBDs, but Spruance had to know where enemy flattops were before he committed his strike planes. Ninety minutes later, another flying boat located one burning carrier, two battleships, three cruisers, and several destroyers, bearing 324 degrees, distance 240 miles from Midway. Twenty minutes later, another report reached the Enterprise—this one placing an enemy carrier bearing 335 degrees, distance 250 miles from Midway, out in the same area as the burning flattop. Conditions still did not permit immediate flight operations by the American flattops, and Spruance decided to wait a bit longer to see what the far-reaching search planes might turn up.

First scheduled flight operations on board the Enterprise that morning involved fighters for the combat air patrol, and “The Big E” readied a dozen F4Fs to go. Among them were six from Fighting Three:

F-13 Lieut. (jg) Leonard |

|

F-15 Mach. Barnes |

F-12 Ens. Adams |

F-10 Lieut. (jg) Brassfield F-21 Lieut. (jg) Mattson |

|

Thach’s contingent was warned by the air department to “pack their toothbrushes” and be prepared to land on board the Hornet. The evening before, Spruance’s staff had assessed the situation and found an excess of F4Fs on board the Enterprise and a lack of them on board the Hornet. Consequently they decided to shift Thach and most of his Yorktown refugees over to the Hornet, where he would take command of the composite fighting squadron. Left on board the Enterprise were Scott McCuskey and Dick Wright with two VF-3 F4Fs (F-3 and the wrecked F-17).

The twelve CAP fighters started taking off at 0825 from the Enterprise, while the Hornet remained quiet. For a change, 5 June proved a very quiet day for the fighters. They encountered no enemy aircraft (there were not many left to encounter!), and what snoopers were out (cruiser floatplanes) did not locate Task Force 16. About the most exciting contact came early, at 0900, when the CAP spotted an object floating on the sea. That turned out to be a disabled PBY flying boat from Midway. The fighters alerted Spruance, who sent the destroyer Monaghan to the Catalina’s assistance.

Later that morning, when Thach’s patrol was over, he took the six VF-3 Wildcats over to the Hornet and landed on board, where they increased the Hornet’s complement of fighters to twenty-nine (fifteen from Fighting Eight and fourteen from Fighting Three). The Yorktowners were made to feel most welcome. Thach assumed command of something designated “VF-3/42/8.” Since December he had personally operated from all five of the Pacific Fleet’s big carriers: the Saratoga, Lexington, Yorktown, and Enterprise, and now the Hornet. Quite likely he was the only pilot to do so. Eddie O’Neill, VF-8’s own executive officer, went on the sick list. Replacing him as temporary XO was Bruce Harwood, while Warren Ford became flight officer. In the ready room, Thach conferred with his pilots to get acquainted and work out a squadron flight organization. He took the opportunity finally to abolish even an administrative organization in six-plane divisions, as that had ruined his escort plans on the fourth. The composite squadron would have four-plane divisions, composed of pairs whose pilots had flown with each other. Thach did not try to integrate the sections, but kept the different squadron pilots and F4Fs with one another.

VF-3/42/8 on board the Hornet about 10 June 1942; standing l to r: Bright, D. C. Barnes, Smith, Freeman, Fairbanks, Dibb, Ford, Harwood, Thach, Carey, Sutherland, W. W. Barnes, Brassfield, Markham, Bain, Crommelin, Leonard, Haas; kneeling: Dietrich, Mattson, Adams, Cook, Merritt, French, Formanek, Starkes, Sheedy, Stover, Hughes, Bass. (RADM W. W. FORD, USN.)

Task Organization, VF-3,42,8, on board the USS Hornet, 10 June 1942

F-1 |

Thach |

F-2 |

Dibb |

F-3 |

D. C. Barnes |

F-4 |

Bright |

F-9 |

Crommelin |

F-10 |

Bain |

F-11 |

Freeman |

F-12 |

Dietrich |

F-17 |

Haas |

F-18 |

Markham |

F-19 |

Starkes |

F-20 |

Smith |

F-25 |

Ford |

F-26 |

Cook |

F-27 |

Formanek |

F-28 |

Hughes |

F-5 |

Leonard |

F-6 |

Adams |

F-7 |

W. W. Barnes |

F-8 |

Bass |

F-13 |

Brassfield |

F-14 |

Mattson |

F-15 |

Stover |

F-16 |

Merritt |

F-21 |

Harwood |

F-22 |

Fairbanks |

F-23 |

Sutherland |

F-24 |

Carey |

Spare: |

|

Source: RADM W. N. Leonard papers.

By 1100, Spruance had determined to his own satisfaction that the Japanese no longer posed a direct threat to Midway. He changed course to the northwest and bent on 25 knots to pursue the carrier or carriers located that morning by the PBYs. Task Force 16 would not be within range to launch SBDs until well into the afternoon. Meanwhile, Browning, the chief of staff, worked up plans that were to see the SBDs, armed with 1,000-lb. bombs, launched at a range of 275 miles. The orders shocked Wade McClusky and his squadron commanders out of their socks. In the presence of the admiral, they protested most vocally to Browning. Spruance overruled the chief of staff, delayed the launch for an hour, and told the air officers to arm the Dauntlesses with 500-lb. bombs. There was no thought of sending the fighters, given the long flight to the target. For the F4F-4 Wildcats, it was simply out of reach.

The Hornet was the first to launch, once Spruance gave the go-ahead. At 1512 she sent aloft a deckload of twelve SBDs from Bombing Eight led personally by Ring, the group commander. Ring set off immediately for the target, said to bear 324 degrees, distance 240 miles. The Hornet’s second deckload, fourteen SBDs under VS-8’s skipper, Walter Rodee, left at 1543. En route, Ring spotted what he believed was a light cruiser, but pressed on to the target, thought to contain one carrier, two battleships, two cruisers, and five destroyers—the remnants of Kidō Butai. Ring took his aircraft out 315 miles, but saw no other enemy vessels. On the flight back he again encountered the “light cruiser,” and this time he attacked. His quarry was actually the destroyer Tanikaze, detached by Nagumo to ensure that the carrier Hiryū had really sunk. The Tanikaze skillfully evaded all the bombs. Rodee had worse luck. He flew out to the end of the navigational leg without sighting any Japanese at all. His SBDs, some burdened by 1,000-lb. bombs (despite Spruance’s orders), had nagging fuel worries as they droned eastward into the gathering darkness.

Meanwhile the Enterprise strike force departed at 1530 after the carrier rotated her CAP. Led by Shumway of Bombing Three, the attack group comprised thirty SBDs from the four squadrons (VB-6, VS-6, VB-3, and VS-5) then operating from the Enterprise. On the flight out, Shumway deployed planes from VS-6 and VS-5 into a scouting line abreast to widen the area of search. By 1727, the group had flown 265 miles without turning up any enemy. Recalling the scouting line, Shumway headed for the contact reported by Ring. There she was, the tough little Tanikaze, but her wily skipper again avoided any hits and extracted a heavy price from the Americans. Antiaircraft fire shot down the VS-5 SBD flown by Sam Adams, the man responsible for pinpointing the Hiryū the previous day.

By the time the first SBDs made it back to Task Force 16, darkness had fallen. The carriers had recovered their CAP fighters and anxiously awaited the return of the dive bombers. Spruance unhesitatingly ordered the carrier landing lights turned on, despite the real danger from Japanese submarines. The SBDs aloft comprised almost the whole of his remaining strike force, none of which he could afford to lose. Some of the pilots faced their first landing at night, but they performed admirably. There were no deck crashes, but VS-8’s Lieut. Ray Davis had to ditch for lack of fuel. The Enterprise brought on board more aircraft than she had sent off: twenty-eight of her own SBDs and five from the Hornet. On her part, the Hornet landed twenty of her brood and one from Bombing Six. Altogether it was a magnificent feat for the pilots, the LSOs, and Spruance himself. When the flattops shut down for the night, more than one pilot gratefully quaffed “medicinal” brandy, duly prescribed to help them relax.

The morning of 6 June, Task Force 16 held a westward course for what would be the final act of the Battle of Midway. By 0500, Spruance was more than 350 miles northwest of Midway, too distant to rely solely on searches sent from there. The Enterprise at 0500 launched a search mission of eighteen SBDs to cover the 180- to 360-degree semicircle to a distance of 200 miles. Also roused early for CAP were six F4Fs from each carrier. The first important contact flashed in at 0645, when a VB-8 SBD (which had taken off from the Enterprise) relayed the position of one battleship, one cruiser, and three destroyers, course 270 degrees, speed 10 knots. Garbled in transmission, the message was received by Spruance as “one carrier and five destroyers.”1 When plotted on the charts, their position was 128 miles southwest of Task Force 16. At 0730, another VB-8 aircraft appeared overhead and dropped a message on the Enterprise’s flight deck. This informed Spruance that the pilot had spotted two cruisers and two destroyers. When added to his chart, they were situated 52 miles southeast of the “carrier” contact or even closer to Task Force 16 than the first group reported.

Two separate groups of Japanese ships, including one carrier, appeared to confront Spruance and his staff. Actually, the only Japanese ships in the area sailed together; they were the heavy cruisers Mikuma and Mogami, badly damaged in a collision with one another early on 5 June, and the destroyers Arashio and Asashio. They had been part of an abortive attempt to bombard Midway; now they limped westward. Midway-based aircraft had harried them the previous day. Now Task Force 16 swooped down upon them.

Not involved in the search, the Hornet was cocked and ready to go. At 0757, she began launching a strike of thirty-four planes:

CHAG |

Cdr. Ring |

1 SBD-3 |

Bombing Eight |

Lt. Cdr. Johnson |

11 SBD-3s |

Scouting Eight |

Lt. Cdr. Rodee |

14 SBD-3s |

Fighting Eight |

Lieut. Ford |

8 F4F-4s |

Mitscher specifically provided the fighter escort in the event “previously undetected air opposition was encountered.”2 Thach and the VF-3 refugees remained behind to fly CAP and give their VF-8 compadres their chance at the enemy. Ford’s escort force comprised the following:

1st Division Lieut. Warren W. Ford, USN Ens. M. I. Cook, A-V(N) Ens. George Formanek, A-V(N) Ens. Richard Z. Hughes, A-V(N) |

2nd Division Lieut. (jg) J. F. Sutherland, A-V(N) Ens. Henry A. Carey, A-V(N) Ens. David B. Freeman, A-V(N) Ens. A. E. Dietrich, A-V(N) |

With Ring in the lead, the Hornet attackers started a slow climb toward 15,000 feet. Meanwhile, at 0815 the Enterprise and the Hornet began recovering SBDs from the search. The pilot who had made the first contact landed on board the Hornet and corrected the erroneous message. Spruance learned no carrier was out there, and at 0850 he advised Ring to that effect.

Ring located the little Japanese task force at 0930 and maneuvered his dive bombers into a good attack position. The Mikuma steamed in the lead, and the Americans thought her a battleship. Compared with her maimed sister the Mogami, missing most of her bow, the Mikuma looked appreciably longer. The Hornet SBDs mostly concentrated on the two capital ships, although a few did take after the destroyers. Ring’s pilots did well. They claimed three hits on the “battleship,” and the Mikuma actually did take two or three bombs in her vitals. The crippled Mogami sustained two hits, and the destroyer Asashio took a 500-pounder on her stern.

Spiraling in with the SBDs, Ford led his eight F4Fs in a strafing run to support the dive bombers. In line abreast, his division of four ganged up on one destroyer, while Jock Sutherland’s four machine-gunned the cruiser (presumably the Mogami). Sutherland retained a vivid recollection of angry Japanese sailors crowded on her stern shaking their fists in hatred as the Grummans roared past at low altitude. Antiaircraft fire was active, accounting for 2 SBDs (1 VB-8, 1 VS-6). The Hornet strike began landing on board their carrier at 1035 after the short hop back from the target. The Hornet air department rearmed the dive bombers for a second attack.

The Enterprise launched her strike planes at 1045. Taking off first was a relief CAP of eight VF-6 fighters, followed by thirty-one SBDs (from all four VSB squadrons) and twelve escort fighters from Fighting Six. Leading the strike was VS-5’s skipper, Wally Short. Short’s orders before departure were to attack the same group of ships plastered by the Hornet, but once aloft, the Enterprise radioed new instructions to seek out and destroy the battleship reported 40 miles ahead of the other target. Almost as an afterthought, “The Big E” despatched the three operational TBDs from Torpedo Six under Lieut. (jg) Laub. He departed with strict orders not to engage if any opposition appeared at all. Spruance would not lose any more torpedo planes if he could help it. On the slow climb to 22,500 feet, Short led the group into gentle S-turns to cut down the rate of advance and allow VT-6’s TBDs to catch up. Unfortunately Laub never did establish contact with the dive bombers. Jim Gray, leading the escort fighters, briefly spotted the TBDs at 1211. He tried radioing the strike leader, but failed to raise him.

Twelve minutes after Gray saw the TBDs, he observed the small Japanese task force. The SBDs pressed ahead to search another 30 miles for the mythical battleship, but Gray led his fighters away to take a closer look at the enemy ships below and offer support in case Torpedo Six attacked. Looking over the Mikuma and the Mogami, Gray likewise thought one of them was a battlewagon. At 1225, he radioed, “There is BB over there!” Three minutes later he added impatiently, “Lets go! The BB is in the rear of the formation.”3 On board the flagship, Spruance was anxious to get on with the attack. At 1235, the Enterprise radioed Short: “Expedite attack and return.”4 He could find no ships ahead of the force already sighted, so he came back over the Mikuma and the Mogami. At 1245, he made ready to attack.

As briefed, Gray waited until the SBDs began to dive, then charged in with his F4Fs to strafe the destroyers. From 10,000 feet, Gray led his division of six F4Fs into a rapid 45-degree dive and barreled in from out of the sun. Responding to the threat, the Japanese tincan heeled over into a tight turn. In close succession, Gray and his pilots opened up with their .50-calibers as they descended below 2,000 feet and held their runs down to masthead level before pulling out. Chunks of metal flew off the destroyer as machine-gun tracers straddled the target and bullets struck home. They ignited a fire and set off a small explosion, visible as the last of the F4Fs rocketed by.

Tackling the other destroyer were six F4Fs led by Buster Hoyle. They approached from off her bow, as the destroyer tried desperately to maneuver out of the way. These VF-6 pilots likewise pressed their runs to within 100 feet of the waves, shot the destroyer full of holes, then in column swung sharply left to avoid the battered Mogami. Hoyle climbed to 5,000 feet, then brought his division around for a second try. Their heavy slugs punched more holes into the thin-skinned destroyer, igniting three fires and a satisfying explosion aft. None of the F4Fs sustained any significant damage, but the destroyers Arashio and Asashio bore souvenirs of the visit. Meanwhile, the SBDs left the Mogami and especially the Mikuma in a bad way, burning and shattered from more 1,000-lb. bomb hits.

While the Enterprise strike planes headed back to their carrier, Ring led a second Hornet wave with twenty-four Dauntlesses. Fighters were unnecessary for this attack; so they remained behind on combat air patrol. The task force had closed within 90 miles of the burning enemy vessels, and with the good visibility, Ring’s crews at altitude simultaneously beheld the target smoking up ahead and their own ships well astern. At 1415, the Enterprise recovered her strike group (except for three SBDs which ended up on board the Hornet) and eight CAP fighters. Meanwhile the Hornet VSB pilots again gave a good account of themsleves. They slammed as many as six 1,000-lb. bombs into the doomed Mikuma, besides securing another hit on the Mogami and a damaging near miss off the Asashio’s stern. In return the Hornet flyers took no losses. Spruance still did not know how many enemy ships were out there and what they were. At 1553, the Enterprise launched two SBDs for photo-reconnaissance, and they secured superb shots of the bruised and burning Mikuma settling into the water. Spruance’s analysts saw her for what she was, a Mogami-class heavy cruiser. So much for the battleship. They expected her to sink shortly, and she did. The battered Mogami and the two destroyers limped off to the west.

The Enterprise handled the dusk CAP; at 1629 she launched twelve F4Fs from Fighting Six, two of which had to abort because of mechanical difficulties. The wear and tear of three long days of battle began to tell on airplanes and aviators alike. After sundown, “The Big E” landed her ten fighters and the two recon SBDs. Now the Battle of Midway was over, as Spruance canceled any further pursuit. The task force had approached within 700 miles of Wake Island, making a Japanese air strike by land-based bombers highly likely the next day if Spruance continued to close on Wake. His destroyers were extremely low on fuel, and the aviators were exhausted. It was time to call it quits. Spruance at 1907 changed course northeast to head for a rendezvous with the fleet oilers Cimarron and Guadalupe. On board the carriers, the pilots finally realized the desperate battle had climaxed in a fantastic victory for the Allies. The night of 6 June was a time for relaxation and celebration. Liquor appeared from hidden recesses in surprising quantity, and on board the Enterprise, at least, the parties were quite lively.

During the night of 4–5 June, the Yorktown’s survival remained in jeopardy. His Task Force 17 jammed with Yorktown survivors, Fletcher had made contact with Task Force 16 and withdrew eastward. Listing steeply as she drifted across the dark seas, the Yorktown had only one companion, the Hughes, whose skipper had orders to sink the stricken flattop should the enemy appear. Still bouncing in the waves not far away was the partially flooded liferaft of VF-3 pilot Harry Gibbs, shot down by a Zero fighter the previous afternoon.1 That terrible night Gibbs tried desperately to stay afloat. At dawn he perceived the flattop, also still afloat, and her faithful escort, and it gave him new hope.

To the east, Task Force 17 that morning was busy transferring Yorktown survivors, including seven VF-3 pilots (Brainard Macomber, Bill Woollen, Tom Cheek, Harold Eppler, Van Morris, Milt Tootle, and Robert Evans), from the destroyers that had plucked them from the sea to the heavy cruiser Portland. On board Fletcher’s temporary flagship Astoria, Buckmaster collected specialists to make up a salvage team to reclaim the Yorktown. When he got them together—a lengthy process—he took the 170 men over to the destroyer Hammann. With the survivors crowded on board the Portland, Fletcher took the opportunity to fuel his thirsty destroyers from that vessel. Fueling took most of the day; at 1800, Fletcher sent the Hammann, Balch, and Benham to rejoin the Yorktown. The rest of Task Force 17 headed south to rendezvous with the oiler Platte and also with the big submarine tender Fulton coming up from Pearl Harbor to take on the Yorktown’s crew.

After dawn that morning, Gibbs had paddled furiously in the direction of the drifting carrier. He tried to raise some response from the tincan’s lookouts, but without success. Floating close by was an empty raft that, although oil-soaked, was larger and more seaworthy than his own; so Gibbs switched over. Exhausted, he fell asleep. Later that morning, someone on board the Hughes noticed the raft, and she came over to investigate. Her crew recognized Gibbs and at 0938 brought him on deck. In all, he had rowed about six miles. Crewmen asked him how he was. He replied that he was all right—then promptly fainted! Gentle hands took him below deck for food, something to drink, a shower to wash off the salt water, and a comfortable bunk. Gibbs slept until midafternoon, then strolled up on deck for a look around.

Around the drifting carrier there was renewed activity. The fleet tug Vireo had joined the little group, and at 1308, she began towing the carrier toward Pearl Harbor. The small tug and her tow could only make three knots or so, but it was a beginning. Gibbs remained on board the Hughes and thus became the only Yorktown fighter pilot to witness the carrier’s curtain scene from start to finish. At 1606 the destroyers Gwin and Monaghan (with Bill Warden on board) moved round the tug and her charge. Unfortunately the Japanese knew that the Yorktown still survived and roughly where she was. A Chikuma floatplane happened upon the carrier during the morning and disclosed her position. The Japanese high command gave the submarine I-168 the mission of finishing her off.

Fletcher on 6 June arranged to divest his warships of the burden of the 2,000-odd Yorktown survivors and also to complete fueling of all of the ships. At 0440, the overcrowded Portland and two destroyers peeled off to the southeast to meet the Fulton. The actual transfer of survivors took almost all day, delayed by a sub scare. Along with the other 2,000 or so Yorktowners, six pilots and 106 enlisted men from Fighting Three went over in coal bags to the friendly sub tender. At the end of the day, the Fulton turned south for Pearl at 17 knots with her fill of Yorktown people. Meanwhile, Fletcher with the Astoria and two tincans met the oiler Platte and fueled. That evening he moved to reassemble his scattered task force, but by that time it was too late for the Yorktown.

Buckmaster in the predawn hours of 6 June arrived on the scene and started salvage work on board the Yorktown. His ad hoc crew initiated counterflooding to reduce the sharp list, attempted measures to restore power, pushed over the side anything reasonably portable (including the two faithful F4F-4s F-6 and F-23 lashed on the flight deck), and even cut away and jettisoned the port-side five-inch guns to decrease topside weight. By early afternoon, things looked much better for the brave flattop. The Hammann lay alongside her starboard side, while the Vireo chugged away, moving her huge tow slowly but steadily.

Still a guest on board the Hughes in the screen, Gibbs around 1330 walked around the destroyer’s bridge. Suddenly an alert sounded, and tremendous explosions erupted next to the carrier. With skill and daring, I-168 had infiltrated the antisubmarine screen and fired a spread of torpedoes. One fish slammed into the gallant Hammann and sank her almost instantly. Two others ripped into the Yorktown’s starboard side, wreaking fatal damage. The destroyers tried fruitlessly to hunt down the I-boat, while the salvage crew fought to overcome their shock and tried to stem the flooding. It was no use. The men abandoned ship for good at 1550. The Yorktown stayed afloat until shortly after dawn on 7 June, when she finally capsized to port. At 0501 with battle flag flying, the magnificent warship slipped beneath the waves. There was nary a dry eye among those who could bear to watch her go, including Ens. Harry B. Gibbs of Fighting Forty-two (temporary duty, Fighting Three).

The crucial spring of 1942 while the Pacific Fleet fought in the Coral Sea and braced for an onslaught directed against Midway, the Saratoga underwent repairs for torpedo damage and also general modernization at Puget Sound Navy Yard. Her air group split between Oahu and San Diego. Knowing he would soon have need of her, Nimitz on 12 May requested that the Saratoga’s repairs be expedited so she could sail around 25 May from Bremerton. Her new commanding officer, Captain Dewitt C. (“Duke”) Ramsey, was to take her on a trial run to San Diego, there to pick up a cargo of airplanes. By 5 June he was to clear San Diego bound for Pearl Harbor. CinCPac the next day directed that Rear Admiral Fitch upon his return to the West Coast from the South Pacific shift his flag to the Saratoga as commander of Task Force 11.

If the Saratoga was the forgotten flattop that spring of 1942, the Fighting Two Detachment became the forgotten fighters, detailed as they were to act as her fighter force when she did leave the yards. In mid-February the VF-2 pilots had settled in at NAS San Diego, standing dawn alerts and trying to keep out of the way of the fledgling carrier pilots of the advanced carrier training group operating out of North Island as well. In March, they received orders to ferry aircraft from the East to the West Coast, traveling by commercial airliners from San Diego to New York and there picking up naval planes for the flights back to San Diego. Each VF-2 pilot made a couple of trips. In late March during the midst of the ferrying, Jimmy Flatley left for parts west to take command of Fighting Forty-two on board the Yorktown. Taking his place in command of the VF-2 Detachment was Lieut. Louis H. Bauer, formerly Paul Ramsey’s flight officer. A 1935 Naval Academy graduate, Lou Bauer had earned his wings in early 1939, reported to Fighting Two, and sharpened his skills as a fighter pilot under such greats as Truman J. Hedding, H. S. Duckworth, Paul Ramsey, and Jimmy Flatley. Likewise in March, the veteran VF-2 NAPs had received welcome promotions. Originally scheduled for warrant rank, Gordon Firebaugh, Theodore S. Gay, and Hal Rutherford obtained commissions as lieutenants (junior grade), while George Brooks became an ensign. Charles Brewer, Patrick Nagle, and Don Runyon fleeted up to warrant rank.

Bauer gradually exchanged his F4F-3As for new F4F-4s and also took over one Wildcat, which seemed a strange bird indeed. On 24 April, the detachment received the first F4F-7 assigned to a West Coast fighting squadron. The F4F-7 was designed as an unarmed, long-range, photo-reconnaissance version of the Wildcat. Fixed-winged, the F4F-7 featured a total of 685 gallons of fuel stored in unprotected tanks, giving it a potential range of 3,700 miles! The prototype had flown nonstop from New York to California, unprecedented for a carrier aircraft. Bauer’s new acquisition (BuNo. 5264) was the second of twenty-one to be produced for the Navy. It certainly was not a fighter—gross weight was 10,328 lbs.(!)—and Bauer likely did not know what to do with it.

The Sara’s repairs and facelift proceeded more smoothly than expected. Bauer received orders to fly north to be ready to rejoin the ship, and on 12 May the VF-2 Detachment headed for Seattle via NAS Alameda. Meanwhile, Don Lovelace had secured orders to reunite the squadron at Pearl Harbor and took ship for Oahu, unaware that the VF-2 Detachment was at NAS Seattle. On 22 May, the Saratoga departed Puget Sound for warmer waters to the south, and Bauer’s troops landed on board to serve as air defense if needed. Duke Ramsey made a swift run along the West Coast and reached San Diego early on the 25th. Bauer’s pilots flew to NAS San Diego, while the Saratoga entered port. She was scheduled for several short cruises off San Diego, both for her trials and to permit carrier qualification landings for the ACTG pilots.

The afternoon the Saratoga arrived in port, several VF-2 pilots flew a glide-bomb practice mission to the exercise area about 15 miles south of San Diego. Fred Simpson rolled into his bomb run from about 10,000 feet and dived in at 70 degrees. He released his practice bombs and started to pull out, but his dive had been too fast. Observers estimated his Grumman straining at 350 knots as Simpson tried to recover at 1,000 feet. Pulling 8 to 10 G’s, the F4F-4 broke up. First the left wing tore off, then the right. Simpson died on impact.1 One of the old-guard aviation cadets, Simpson had earned his wings in November 1937 and flew over three years with Bombing Two. In March 1941 he had received a regular commission and his posting to Fighting Two. Fighting Two Detachment went to sea on board the Saratoga from 29 to 31 May, then returned to NAS San Diego.

Worried by the impending Japanese offensive against Midway, CinCPac on 30 May told Ramsey to sail as soon as possible for Pearl, even though Fitch, the task force commander, had not yet reached San Diego. Nimitz expected the Saratoga to clear Pearl on 6 June and get out to Midway about two days later, there to join Frank Jack Fletcher’s Task Force 17 with the Yorktown. Ramsey got under way early the morning of 1 June and nosed his newly designated Task Group 11.1 past Point Loma and into the Pacific. Already hoisted on board the Saratoga was a cargo of four F4F-4s, forty-three SBD-3s, and fourteen Grumman TBF-1 Avengers. At 1310, the Sara began landing her air group:

Often attributed to the Enterprise, these Wildcats appear to be former VF-2 Detachment F4F-3AS used by ACTG Pacific during carrier qualifications on board the Saratoga cruising off San Diego, late May 1942. (NA 80-G-14784.)

Commander, Saratoga Air Group, |

||

|

Cdr. Harry D. Felt |

1 SBD-3 |

Fighting Two Detachment |

Lieut. Louis H. Bauer |

14 F4F-4, -7 |

Scouting Three |

Lt. Cdr. Louis J. Kirn |

22 SBD-3 |

Bauer’s outfit had swelled in May to fourteen with the inclusion of six NAPs who had recently graduated from ACTG, Pacific. The VF-2 Detachment on 1 June comprised:

Old VF-2 hands: Lieut. Louis H. Bauer, USN Lieut. (jg) Gordon E. Firebaugh, NAP, USN Lieut. (jg) Theodore S. Gay, NAP, USN Lieut. (jg) Harold E. Rutherford, NAP, USN Ens. George W. Brooks, NAP, USN Gunner Charles E. Brewer, NAP, USN Mach. Patrick L. Nagle, NAP, USN Mach. Donald E. Runyon, NAP, USN |

Newly assigned: Lee P. Mankin, AP1c, NAP, USN Robert H. Nesbitt, AP1c, NAP, USN Harold M. O’Leary, AP1c, NAP, USN William J. Stephenson, AP1c, NAP, USN Clark A. Wallace, AP1c, NAP, USN Stanley W. Tumosa, AP2c, NAP, USN |

Other pilots, mostly fresh from advanced training, rode the Saratoga out to Pearl to join other squadrons. Ramsey set a westerly course at a steady 20 knots.

Missing his new command by a day and a half, Aubrey Fitch on board the Chester arrived at San Diego the afternoon of 2 June. The transports Barnett and George F. Elliott docked at the destroyer base inside San Diego harbor and disgorged the multitude of Lexington survivors. The fighter pilots split according to their orders. Paul Ramsey and the original VF-2 hands waited for new assignments, while Scoop Vorse took charge of the VF-3 refugees, trying to get them back out to Pearl to rejoin the squadron. Noel Gayler headed east to become a test pilot. Jimmy Flatley happily reported to NAS San Diego and his nascent Fighting Ten, ready to implement the ideas he had so carefully thought out on the voyage back. Fitch waited until the Chester could be refueled and reprovisioned, so he could ride her out to Pearl.

The Saratoga’s return to the war zone was uneventful except for some activity on 3 June. At 1026, a radar contact bearing 007 degrees, distance 26 miles afforded an opportunity to practice a CAP scramble. Six VF-2 F4F-4s roared off the flight deck and checked out the bogey, which proved to be an Army B-17 Flying Fortress on a ferry flight to Oahu. At 1215, another contact activated the radar scope, and five fighters took off. A few minutes later, one of the five, NAP Tumosa, lost power at 5,000 feet and tried to get back to home plate for a deferred forced landing. The Saratoga was not prepared to recover him, and after circling three times, Tumosa had to put his Grumman into the water. The destroyer Smith quickly rescued him unharmed, offering practice of another sort, but at the price of F4F-4 BuNo. 5182.2

While the Saratoga ate up the miles toward Pearl Harbor, the Pacific Fleet slugged it out with the Japanese at Midway and triumphed in decisive victory. At 0545 on 6 June, the Saratoga despatched her air group for fields on Oahu and headed in. She anchored at berth F-2 off Ford Island after an absence of nearly four months. The situation was not nearly as grave as it appeared two days before! With the victory, details of which were very sketchy, the CinCPac staff first thought to send the Saratoga out to join Task Force 16 for raids on the newly acquired enemy holdings in the Aleutians. With the second and fatal torpedoing of the Yorktown that afternoon, Nimitz decided not to risk an inexperienced carrier and ad hoc air group in combat. He assigned Duke Ramsey a new mission: ferry replacement aircraft to Spruance’s carriers, then return to Pearl.

The Saratoga’s cruise would provide carrier squadrons long based ashore the chance to stretch their sea legs. Alerted for duty on board the carrier were the outfits that had arrived at Pearl on 29 May: Roy Simpler’s Fighting Five, Fighting Seventy-two under Mike Sanchez, and the Torpedo Eight Detachment with Grumman TBF-1 torpedo planes led by “Swede” Larsen. Given the news blackout on Oahu, Simpler’s troops, who considered themselves the legitimate Yorktown fighting squadron, wondered what was happening to the old lady and were surprised at orders to embark on board the Saratoga. Also eager to go were those elements of the Yorktown Air Group left on the beach, the “real” Scouting Five and Torpedo Five. With all of the fighters now available, VF-42’s Chas Fenton and Vince McCormack, unhappily waiting at Ewa, had to bide their time. They took custody of the sixteen rookie VF pilots who had come out on board the Saratoga and maintained a collection of battleworn F4F-3s, survivors of Coral Sea, while they awaited delivery of some F4F-4s. Lou Bauer discovered on reporting in that his own superior, Don Lovelace, had gone out on board the Yorktown. Owing to radio silence, he did not know that Lovelace had died on 30 May. Bauer exchanged several of his F4F-4s and gratefully turned over to NAS Pearl Harbor the hybrid F4F-7 for the time being. He and eight pilots were to reembark on board the Saratoga, relegating most of his rookies to Fenton at Ewa.

The USS Saratoga (CV-3) in Pearl Harbor, 6 June 1942, after her voyage from San Diego. (NA 80-G-10121.)

On 7 June, Ramsey’s redesignated Task Group 11.2 set sail from Pearl with the Saratoga, five destroyers, and the oiler Kaskaskia. Jake Fitch missed the boat again. His temporary flagship Chester had departed San Diego on 4 June and was still en route to Pearl. Around 1100, the Saratoga began landing part of her improvised air group. All of those aircraft plus those previously hoisted on board the Saratoga totaled 107 (47 fighters, 45 dive bombers, and 15 torpedo planes) organized as shown in the table. His aircraft safely tucked on board, Ramsey set course to the northwest.

Commander, Saratoga Air Group, |

||

|

Cdr. Harry D. Felt |

1 SBD-3 |

Fighting Five |

Lt. Cdr. Leroy C. Simpler |

18 F4F-4s |

Fighting Seventy-two |

Lt. Cdr. Henry G. Sanchez |

20 F4F-4s |

Fighting Two Detachment |

Lieut. Louis H. Bauer |

9 F4F-4s |

Scouting Three |

Lt. Cdr. Louis J. Kirn |

25 SBD-3s |

Scouting Five |

Lt. Cdr. William O. Burch, Jr. |

10 SBD-3s |

Ferry Detachment |

Lieut. Keith E. Taylor |

9 SBD-3s |

Torpedo Five |

Lieut. Edwin B. Parker |

5 TBD-1s |

Torpedo Eight Detachment |

Lieut. Harold H. Larsen |

10 TBF-1s |

“HOW GOOD LAND WILL LOOK THIS TIME”

The seventh of June, the day the valiant Yorktown gave up the ghost, Task Force 16 with the Enterprise and the Hornet retired eastward for a vital fueling rendezvous. Other than for normal flight operations (search and inner air patrol), the aviators spent a quiet day trying to pick up the pieces. Spruance’s two carriers had on hand a total of 131 aircraft (just over one hundred short of the 4 June figure, including the Yorktown) of which 118 (54 fighters, 61 dive bombers, and 3 torpedo planes) apparently were operational. To the southeast, Fletcher spent the day completing his fueling, then headed out to meet Task Group 11.2 coming up from Pearl. That evening, CinCPac issued specific orders for the second phase of the Midway operation. He set a 10 June rendezvous between Fletcher’s Task Force 17 (which by that time would include the Saratoga) and Spruance’s Task Force 16 in order to transfer aircraft from the Saratoga to the other flattops. This completed, Fletcher was to turn south for Pearl Harbor.

For Ray Spruance’s Task Force 16, Nimitz had other ideas. Concurrent with their assault on Midway, the Japanese had rampaged in the Aleutians and evidently intended to occupy a number of positions in the island chain. The enemy had used strong forces, including carriers, and Nimitz thought the enemy might be up to further mischief in northern waters. Thus Spruance with his two carriers, five cruisers, one light cruiser, eight destroyers, and a fleet oiler was to proceed north to “Point Blow” (Lat. 48° North, Long. 172° West), there on 12 June to rendezvous with elements of Rear Admiral Robert A. Theobald’s Task Force 8. Spruance was to come under Theobald’s overall command in order to “seek out and destroy enemy forces in the Aleutians.”1 For the aviators, there boded uncomfortable, even perilous flying conditions over cold Alaskan waters renowned for fog, icing, and other noxious forms of bad weather.

The weather on 8 June round Task Force 16 seemed a foretaste of what the pilots could expect in the Aleutians. The Hornet lost two SBDs in the poor visibility, one of which found sanctuary on Midway. Good thing the weather was not that way on 4 June when the Japanese first attacked! At 0430, Spruance’s ships had begun fueling, destroyers first, from the oiler Cimarron. It was their first drink from an oiler in nine days. Later the oiler Guadalupe and four destroyers joined up to hasten the fueling. The tincans took the opportunity to transfer aviators they had fished out of the water the past several days. Bill Warden returned to Fighting Six on board the Enterprise, while VF-8’s Jim Smith made it to the Cimarron. That day came definite word of the Yorktown’s demise, which saddened everyone and robbed the victory of some of its sweetness.

Fletcher’s truncated Task Force 17 (the Astoria, the Portland, and three destroyers) at 1112 made contact with Ramsey’s Task Group 11.2, and early that afternoon, he transferred his flag to the flattop. That accomplished, the reconstituted Task Force 17 steamed northwestward to contact Task Force 16. The Saratoga conducted the usual search and inner air patrols, but Ramsey kept his fighters under wraps.

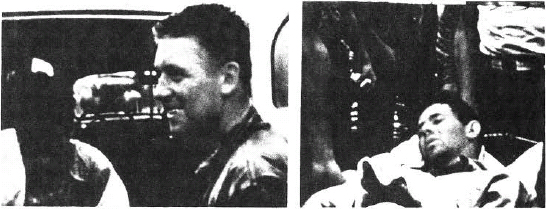

The eighth of June also proved a red letter day for the VF-8 pilots lost on the ill-fated 4 June escort mission.2 That day PBYs operating north–northeast of Midway finally happened upon some of the rafts and rescued their occupants. One Catalina bellied into the sea to recover the irrepressible John McInerny and section leader John Magda. The two had hoped for an early rescue on 5 June when they happened to see Task Force 16 pass by in the distance (as Spruance headed toward Midway that morning), but no one spotted them. Now flown to Midway, Magda and McInerny looked in good shape and high spirits as they clowned with John Ford’s motion picture photographer at the seaplane base. McInerny, however, was deeply worried about the consequences of his turning the fighters back on 4 June, but nothing was ever said to him about it.

A second PBY that day found Frank Jennings and Hump Tallman not too far from where the other picked up Magda and McInerny. As Tallman stepped out of his orange raft, a PBY crewman noticed its interior scribbled with a lengthy message. After ditching, Tallman had set down in detail his recollections of the mission, anxious that it be preserved. Both he and the crewman tried in vain to retrieve the raft, but it floated away and had to be left behind. Also rescued that afternoon was Johnny Talbot, weak from his lonely ordeal. Lieut. (jg) Francis M. Fisler’s PBY from VP-51 spotted his raft and whisked him back to Midway for treatment. Still missing were five VF-8 pilots, but Talbot helped point out where they might be.

(Left photo) Ens. John McInerny (right) and Ens. John Magda of VF-8 at Midway after their rescue on 8 June by a PBY. (Right photo) Ens. Johnny Talbot of VF-8 arriving 8 June at Midway after being picked up by Lieut. (jg) Frank Fisler’s PBY. (These photos are stills from Cdr. John Ford’s The Battle of Midway.)

The morning of 9 June, one of Fisler’s sharp-eyed crew spotted the two rafts containing Pat Mitchell, Stan Ruehlow, and Dick Gray. The three were emaciated, tired, sore, sunburned, hungry—and gloriously glad to be alive. The PBY picked them up at a point bearing 047 degrees, distance 131 miles from Midway, and one of the grateful castaways (evidently Ruehlow) presented the crew with a “short snorter,” a ten-dollar bill upon which the details of the rescue were written.3

For six days the three VF-8 pilots had drifted slowly to the northwest, carried by the current. On 5 June they had several times sighted search planes and tried signaling them with a hand mirror. After dark that day came a really big scare. In the blackness a shark repeatedly nudged both rafts. Finally the bump was violent enough to spill both Ruehlow and Mitchell into the water. Ruehlow actually brushed the shark and gashed his right hand on its rasping skin. He lost no time in making it to Gray’s raft, while Mitchell clambered into the now vacant but damaged second raft. The skipper had to lie in the nearly swamped boat with his legs dangling in the water, but very fortunately the shark did not persist in its attacks. On 6 June the three dipped into the survival rations so fortuitously saved by Gray. Even though severely rationed, the food and water did not go far. After another blistering day and cold night in the water-soaked rafts, they secured their first replenishment of fresh water from a rain squall, allowing them to refill their canteen. Rescue came none too soon, as far as they were concerned. The VF-8 pilots spent a few days at Midway, then they were flown back to the naval hospital at Pearl Harbor.

While the VF-8 pilots were recovered, other survivors of the Midway battle made it back to Pearl. At 1530 on 8 June, the submarine tender Fulton docked at the submarine base inside Pearl Harbor. There to greet the Yorktowners were Nimitz and the rest of the fleet brass, shaking hands and showing much good cheer. Headed ashore were Macomber and Woollen from VF-42, and from VF-3 came Cheek, Tootle, Eppler, Morris, and Evans. The seven traveled out to Ewa to join Fenton’s contingent. Harry Gibbs came in the next day with the salvage survivors on board the Gwin and the Benham.

The VF-8 “short snorter” $10 bill. Obverse legend:

This was with Lt. Comdr. Mitchell, Lt. Stanley Ruehlow, Lt. j.g. Richard Grey (sic) when they went down at sea June 4th, 1030, 1942, in three F4F-4 Grumann (sic) fighters from the U.S.S. Hornet. In a PBY-5B we picked them up at 0930, June 9th, 1942. We were operating out of Midway on a course of 047° T. 134 mi. distant from Lat. 28° 23′ Longitude 177° 21′

They spent the six days in two rubber boats with one set of rations. All are well Wind 32 kts. from 190° T.

Crew #7 of VP-51

Lt. j.g. F.M. Fisler

Ens. Jerry Crawford

Ens. R.L. Cousinslak

NAP Ward AP2c

S.R. Topolski Amm2/c

C.S. Lewis Amm2/c

C.B. Brown Arm2/c

“Short snorter” reverse:

On June 8th, 1942 at 1536 we had picked up Ensign Talbot near the spot we found the other three the next day.

It has been our deep regret that we couldn’t find Ens. Kelly and Hill who have been lost near these three other men

R.I.P.

(Source of VF-8 short snorter: Bowen P. Weisheit, Ens. C. Markland Kelly, Jr. Memorial Foundation.)

For the carriers, 9 June was a quiet day. The Enterprise had the duty, but the fighters did not fly. Jim Smith got back to the Hornet while she refueled from the oiler Cimarron. Task Forces 16 and 17 made contact the morning of 10 June, for all the good it did them. It was “foggy, foul weather—a day in bed for all hands,”4 recorded the VF-6 diary. Fletcher and Spruance marked time on a southerly course, waiting for the skies to clear. The Enterprise did not get a glimmer of the “floating drydock” (as her pilots unkindly dubbed the Saratoga) until late afternoon. The aircraft transfer finally took place the morning of 11 June. To the Enterprise, the Saratoga flew ten SBDs from Scouting Five (the “real” Scouting Five) and five TBDs from Torpedo Five. The Hornet received the nine replacement SBDs of the ferry detachment and the ten Grumman TBF-1s of Larsen’s Torpedo Eight Detachment. The TBFs excited special interest, as this was the first time Task Force 16 had seen the big Grumman torpedo planes operate on a carrier. The reinforcements gave Spruance’s two carriers a total of 163 aircraft on board (57 fighters, 87 dive bombers, and 19 torpedo planes, not all flyable).

Its mission completed, Task Force 17 by 1100 had turned south for Pearl, while Spruance shaped course north for the next day’s rendezvous with Task Force 8 and further combat in Aleutian waters. A few hours later came a welcome reprieve. Nimitz relented and ordered Task Force 16 home. With the Japanese on the run in the Central Pacific, he had no need to risk the carriers in raids on the enemy toehold in the Aleutians. Also on 11 June, the carrier Wasp traversed the Panama Canal and reported for duty with the Pacific Fleet. With the loss of the Lexington and the Yorktown, however, that still left CinCPac with only four fleet carriers—but the Japanese did not have even that many big carriers after Midway!

Steaming southeastward into warmer waters, the two task forces gratefully enjoyed better weather on 12 June. The Saratoga that afternoon launched all of her operational fighters. Simpler’s Fighting Five and Bauer’s VF-2 Detachment (twenty-six F4F-4s all told) flew a welcome gunnery training flight, while Sanchez led nineteen VF-72 fighters in squadron tactical drills. One pilot did not find the exercise much to his liking. At 1447, Lieut. (jg) Robert W. Rynd of VF-72 had engine trouble and ditched. The destroyer Russell recovered him unharmed. On board the Enterprise, VF-6 pilots handled the last two inner air patrols, but no one minded. They were on their way home!

The morning of 13 June saw a massive fly-in of carrier planes to fields on Oahu. Somewhat ahead of the rest, the squadrons of the Saratoga Air Group took off beginning at 0650 and made for NAS Pearl Harbor. Later that morning Task Force 17 entered port. Task Force 16’s turn came a little later. The Enterprise Air Group flew to NAS Kaneohe Bay, pleased to find there, “a band to meet us and free beer right on the field.”5 The Hornet launched her squadrons for MCAS Ewa. Thach’s VF-3/42/8 pilots all took care to get into their own squadron’s airplanes for the scheduled flight in. When they touched down, Thach and the VF-3 pilots taxied to one part of the field, Harwood’s VF-8 troops to another, while Leonard led the VF-42 personnel to a homecoming at the hangar where Fenton, McCormack, and company had set up shop. There was no formal goodby between Thach and the VF-42 pilots who had served him well. There just was not time for that. He flew over to Kaneohe to reunite Fighting Three. Leonard personally did not see him again for two years. That was the way it went. The first phase of the Pacific War was over, but most of the work remained to be done.