INTERVIEW NO. 6

OLETHA BARNETT

OLETHA BARNETT

What’s your full name and where you were born?

My full name is Oletha J. Barnett, and I was born in Morris, Oklahoma. I grew up in Okmulgee. Oklahoma. Part of the time in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, and part of that time on our farm in Morris, Oklahoma. Morris is 12 miles south of Okmulgee.

Can you describe your childhood home and neighborhood?

We had a 160-acre farm, and there were no neighbors per se, other than farms that were distanced from us. On the farm, we had cows, horses.… Mama had chickens and various things. And in the little town where I went to school, the neighborhood was segregated. It was a quiet neighborhood, and there was the Black part of town and the white part of town. It was completely segregated. I grew up in a segregated elementary school and high school, and they did not integrate until the year after I graduated from high school. And it was a neighborhood where everybody knew everyone. It was a small town. I think the population at that time was around 13,000.

On the farm, it was just our little world and we were happy. We could roam the land. And we had ponds where you could go fishing. My mom and some of the siblings would go fishing; I didn’t particularly care for fishing. My older sisters and brothers worked the land, but the younger ones didn’t, because by then my dad was hiring people to work the land. I do remember one summer, once the older ones were gone and married—see, we were much younger—he decided that we should work it like the older kids did. But we didn’t do so well!

I grew up with six sisters and three brothers, but I have 22 siblings. My dad was 20 years older than my mom, and there are two sets of us. And so that’s why I say “the older group” did the farming. By the time we came along, some of the older ones were in the same age group as my mom. So, 22 total, I grew up with nine of them. Out of the first set, there were 12 of them, and there are only three of them left. And, by God’s grace, my oldest sister is still living. She’s 103 years old. Longevity is in our family, and I hope I’m one of those.

Where do you fall in the order of the siblings?

I am the fourth from the end. Both my parents had been married before, and I’m the first of the last set. There are three younger than me.

Did you have chores on the farm?

Not really … I’m trying to think of what chores we did. Because like I said, he hired people. We just went to school. By the time the younger set came along, Mom and Dad were older. And so, they weren’t doing the same kind of farming that we had done at one time. Now, my mom did do canning, and most of the older siblings would help with that. I’m sure I did some chores. I cleaned up the house.

What all were y’all growing on the farm?

We grew peanuts and we grew cotton. It was 160 acres of land: 80 in one spot, and 80 in another spot. They weren’t together.

How were your parents able to purchase this land?

My dad was quite phenomenal. But he was much older. And he purchased that land before they were married. That was during his first marriage. And he farmed, sold cattle, and various other things, and was able to pay for the land in a time when you didn’t have a lot of Black landowners.

He came from Montgomery, Alabama, when Oklahoma was not even a state. He was born in 1896. There was a race incident. I can remember my dad telling me about it. There was a racial incident in Montgomery, Alabama. One of his uncles was a mail carrier. And something happened.… He had gone into a store to warm himself in the wintertime. And there was a white man who slapped him. And so, as my dad put it, he defended himself. And they left early the next morning on a train, and ended up in Oklahoma Territory. It was not a state.

There’s a quite interesting story that goes with that, because you got to realize that at that time, it was early 1900s, around 1907. At that time, obviously, you’re going to lose track of your family in Alabama if you’re in Oklahoma. I can remember there was a traveler who had come to our little town of Okmulgee, and I believe my dad may have been in his late sixties or early seventies. And there was a lady in Montgomery, Alabama, who was wondering what happened to her family all those many years ago. And if there were any Barnetts in that little town. And someone had directed her to our home in Okmulgee. So, my dad wrote the lady and named all of his people. One of those people that he named was Aunt Honey. And amazingly, she actually turned out to be his Aunt Honey, which of course was not her first name, but that was the name he remembered. After that, one of my sisters flew down there with Dad, and that’s how we got reconnected with the people in Alabama. That was my dad’s very first time being back in Alabama since then, and he told me, his church was not there, but the tree outside the church that he used to play under was still there.

When we reconnected with the Alabama family, people would say, “Well, actually, you all are Smiths, not Barnetts.” My great-great-grandfather’s name was Dick Lewis Barnett, but he was a slave owned by Sol Smith. He was what they called a house n-i-g-g-e-r.

Well, he ended up joining the Union Army. He had gone to war along with his master, who fought for the Confederacy. Like a lot of others, when he had the chance, my great-great-grandfather escaped and went to join the Union Army. Years later, he was attempting to apply for the government pension as a Union Army veteran. As a part of the process, they wanted to take a deposition from him to find out how a slave ended up in the Union Army.

That happened a lot—a lot of enslaved people went to join the Union. But not a lot from the Deep South. Is that what raised their antenna?

Oletha’s great-great-grandfather, Dick Barnett, and his wife; photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

They took the deposition because of an issue with his name. He had always gone by Lewis Smith. Then one day, he learned that white people took the last name of their fathers. See, he’d never known that. As a slave, the people he knew had the last name of the slaveholder. Well, his mother told him that his father’s last name was Barnett, so he took the last name of Barnett after the war. When he applied for the pension, he applied as a Barnett, but when he served, he was under the Smith name. So that’s why they took that deposition, they wanted to see if it was really him. His deposition can be found in the National Archives.

Another thing about this is the way we found out about the deposition. My nephew was in therapy, and his therapist was a young white man. After learning more about our family, the therapist told my nephew, “We might be related.” Turns out that we were, and it was actually the young white man who told us that there was a deposition from my great-great-grandfather. This was some years ago before we had ancestry services and all these tools. So the Blacks and the whites are connected in a lot of ways, right? Slavery forced us to be connected.

I also remember that my dad hated the military. He always hated the military, and it’s because of how my great-great-grandfather was treated, and how he had to fight for his pension.

So when your family fled Montgomery, who all left?

It was my grandfather, my dad’s dad. And then there was my dad’s first cousin, Thomas. I don’t know who all left, but those were the two people that I knew. They ended up in Oklahoma. There may have been some who left, and later ended up in California. Because my dad’s brother, Uncle Alexander, lived in California.

Why did they have to leave so suddenly?

Well, you gotta remember it’s late 1800s. And we’re talking about Montgomery, Alabama. And so, we know why they had to leave. For fear of their lives. I know they had to get out of town. Yeah.

What was school like for you growing up?

I grew up in a segregated school. And I just thought school was wonderful. All of my teachers were Black. All of the students were Black. The teachers knew our families. And so we just went and learned. I later learned from children who had gone to the integrated schools that it was totally different for them. Because our teachers always pushed us, and encouraged us to go to college, and told us we could be anything that we set our minds to. However, as I understand it, at the other schools, they didn’t have much expectation for the Black kids. They didn’t talk to them in the same light. In fact, one person I know was told as a student that, because of the curse of Ham—which we know is a lie—that Blacks are inferior, and so he just needed to accept the state that God has made him in, to be subservient to the whites.

I loved math, because my dad loved math. He also built houses. Because I liked math, I majored in math in college. Math was my favorite subject, and my dad and I did math problems; I think he did that just because of his building and all.

I had two favorite teachers. My fifth grade teacher was Mrs. Jones, and she was my favorite. And my absolute favorite was Mrs. Rodemore, my sixth grade teacher. And I just loved her. When I graduated from high school, it had been many years since I had seen her. And lo and behold, to my amazement, there she was. And she brought me a gift after all those years!

They kept up with us. The teachers. They took a genuine interest in us.

What did you do for fun when you were a kid?

I read. I loved to read. I’d just curl up with a book and read. Of course, fun was built in. Because we had a house full of other kids. And so we played jokes on each other and looked at TV, and read, you know, things like that.

We did not have a lot of social events at school. The only thing I’m kind of remembering was a Halloween party. Mom had let us go to it, and Daddy found out when he got home. He came and got us and he said Halloween was foolishness. So they probably did that every year, but we didn’t get to go.

Osage Avenue Christian Church in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, is where I grew up. And my grandmother was one of the founders of that church in that little town. And I can remember the older people there would always say I reminded them so much of my grandmother, my father’s mother.

The grandmother to which I’m referring was dead when I was born. I did know my dad’s dad, and my mother’s mother, my granny. I was very close with those grandparents.

My grandmother was at our house every day. She lived on one street and we lived on the other. She’d come down that alley to our house. Then, there was a time when she lived across the street, so you know, it was seamless.

Even my great-grandmother, when I say down the alley, it was my great-grandmother’s house. My granny was down there a lot with her mom. And my great-grandmother went to bed at 8 p.m. every night. And she had a telephone, but the neighbors didn’t. So, lights out at 8 p.m. I knew the lights were supposed to be out, but I tipped in there when Granny was asleep. And so, I turned the light on so I could read. Then, there was a knock at the door and a neighbor wanted to use the phone. She figured Granny was up because the light was on. Right then, I knew I was in trouble!

In reference to my great-grandmother, I didn’t realize this until I was an adult for many years … she would love for me to read to her. And I would read, and I would look up every now and then, and she had this smile of joy on her face like no other. I would read, and I would love to look up and see that look on her face. And you know, I was probably 40 years old or more before I realized what that look was. She couldn’t read.

She could not read. Based on her time of life, when Blacks didn’t go to school—and in fact, at that time, it was illegal for us to read and write. So she just loved the fact that her great-granddaughter could read. Yes, she loved it.

And my grandmother also could not read. She would write an X for her name. My granny was born in the 1800s, and she would make an X for her name since she couldn’t read. And I find it interesting that there was a mindset that Blacks were illiterate. But that was set in motion by society making it illegal. Right.

Did your great-grandmother or others talk about slavery?

You know, I was reflecting on that question pondering that, but I don’t remember them talking about it. And I don’t know why. Maybe they wanted a better time for us, and not to remember what had happened. My great-grandmother had been a slave. And she was referred to as a Choctaw Freedman. Grandma Harris.

And she never spoke of it. She would cook for us and do things with us, but she never spoke of it. Nor did my grandmother. I don’t know if there was shame associated; I don’t know why. It’s even like the Tulsa riot that happened about 20 years before I was born. We are 35 miles south of Tulsa. My sister Ruth said that she heard Mom and Dad whispering about it once. And, even after all that time, they would whisper. It was almost like the Black people that I knew who were living in Tulsa around that riot time had decided not to discuss it. But you can just imagine that, here you are in this thriving community where money was turning around 18 times, and the majority culture is looking with hatefulness and jealousy. Greenwood—they called it Black Wall Street. It was a thriving metropolis. Businesses everywhere. And they bombed them.

And not only did they drop bombs on the community to make sure it didn’t go anywhere, but they also came in and built a freeway over it and cut it off. You couldn’t even drive all the way through it like you used to. They closed off whole streets and everything. And so there was a lot of hopelessness, helplessness. But I do not recall any story that my grandmother or my great-grandmother told like that. And they probably would not have told us as kids.

You could be lynched or anything else for even raising the issues. And so, there was a chilling effect put on it. And that’s why there was a quietness. There was an acceptance of the plight and the condition, I believe. You know the letter, Willie Lynch? The making of a slave, how you break down a person. Their emotions and their psyche, and everything else. And so … and that’s why you saw a lot of Black elders with their heads bowed down, and you had this rule in the South where you couldn’t look a white person in the eyes, and so their heads would be down. And that was passed down in order to protect us. I don’t even think it was that they were trying to forget it. They were trying to protect us.

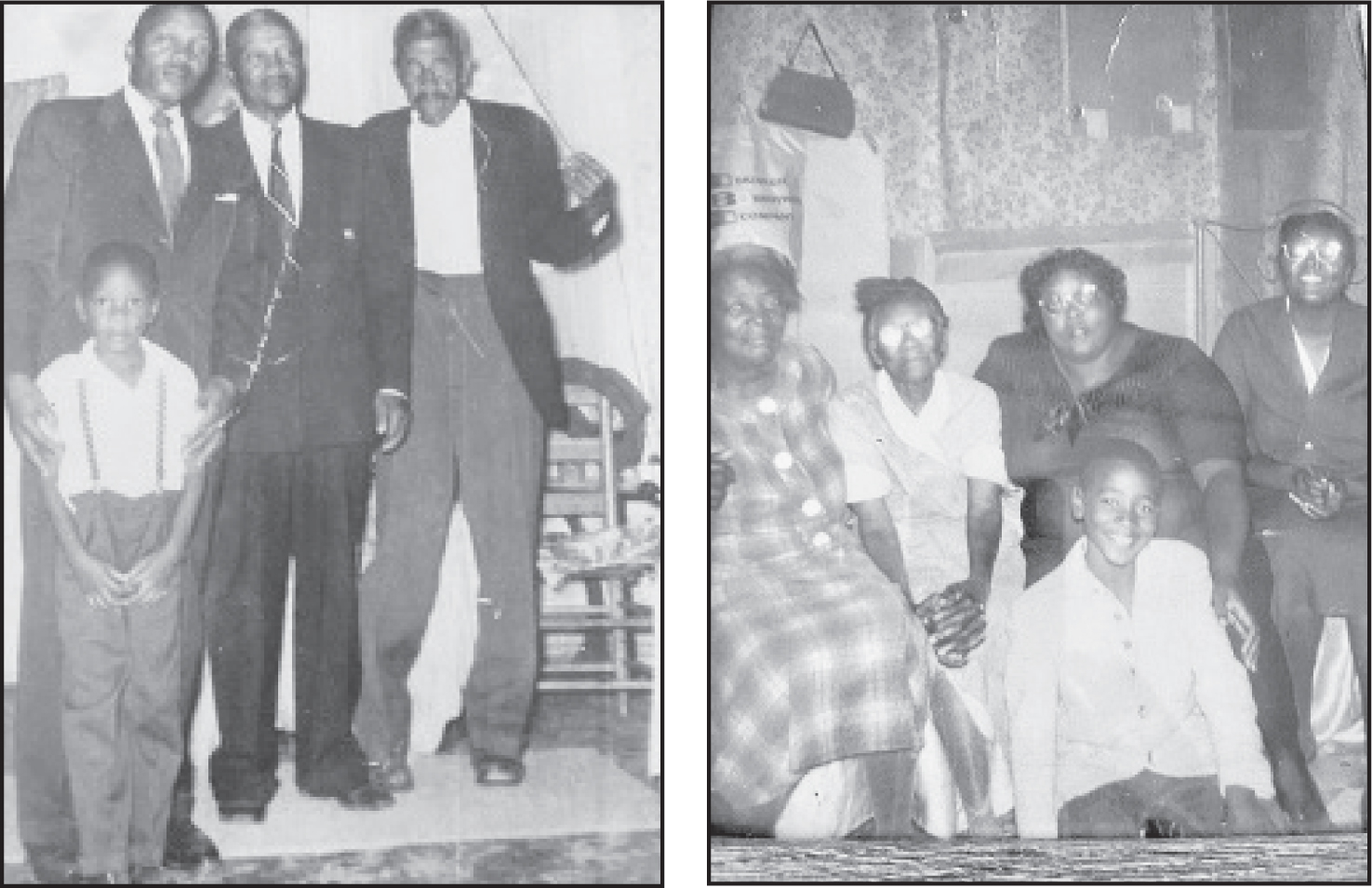

On the left, Oletha’s father’s side of the family, including her brother Carl, her father, and her grandfather Frank (son of Dick Lewis Barnett). On the right, Oletha’s mother’s side of the family; from left: Oletha’s grandmother, great-grandmother, her mother, her sister, and her nephew.

Here’s the thing to remember about Jim Crow. There was a period of time when Jim Crow was legal. But never forget that the baggage of slavery was passed down. Jim Crow is still with us, just in different ways. When you change the law, you don’t change the hearts. Jim Crow is still with us in a different form. I’ll give you one example. After the Civil War, and after Reconstruction, they brought in the Jim Crow laws and the Black Codes, and voting was a huge issue. They did everything under the sun to keep us from voting. The 14th Amendment gave us the right to vote, but no, we still got to have special legislation. That’s still the baggage of Jim Crow. And then, even before 1965, you had [to have] all those other interim laws trying to give us the right to vote. Getting rid of poll taxes and literacy tests, and all of that. Even today, you still see the suppression of the vote.

So, it’s still with us. We still have that as an issue. That’s part of the baggage of Jim Crow; it’s still with us, make no mistake. Passed down in the psyche of the whites, passed down in the psyche of the Blacks.

When you were growing up, were you aware of any unwritten rules that govern race relations?

There are so many, you can’t even envision it. There was an incident that happened with me. That was an unwritten rule, but it came about as a result of Jim Crow and segregation and the hatred of Blacks. Here’s a little story: a number of years ago, I was in Maryland driving to a friend’s house. This was before GPS. I realized I was on the right street, but going in the wrong direction. So I make my little U-turn in the street to go in the other direction. And my friend who was riding with me said, “What is wrong with you? Why did you make that U-turn in the street, instead of just coming up in somebody’s driveway and backing out?”

See, it had floated up from my subconscious. You don’t know what’s in your psyche until something triggers it. I was always told as a child that you don’t turn around in the driveway of a white person’s home, or they will shoot you. And so that floated up from my subconscious. I believe that it’s untold, and we can’t even scratch the surface of the impact of it. That unwritten rule, see, my mom had told me that to protect me. But I wasn’t even aware that I was operating from my subconscious until somebody raised the issue. Had that issue not been raised, I would have gone along without ever thinking about it. Thinking about getting shot at the time, I was just acting on what I knew.

Once, we were driving near Henrietta, Oklahoma. And my mom said, Henrietta used to have a huge sign on Main Street that said “N-I-G-G-E-R, don’t let the sun go down on you in Henrietta.” It was a sundown town. A sundown town is a town where Blacks have to be out by before sundown, or you would be hanged; in fact, a white woman told me that her mother would drive through a town called Poletown to take her to school every day. And she once asked her mother why it was called Poletown. Well, her mother told her in a matter-of-fact tone that it was called Poletown because if Blacks weren’t out of town before sundown, they would be lynched from a pole.

So, people talk about the South, but when Blacks escaped to the North, there were a lot of those Northern places that had sundown towns, also. The North may have been different from the South, but the North had its own racial issues with sundown towns, and so much more. It’s just steeped throughout the country, and it’s an ugly legacy of the United States of America.

My college, Langston University in Oklahoma, was predominantly Black. One of my professors said, “If you got to drive through the South, you’d better get through the South before it’s dark.” And the college president’s wife told us that they were driving through the South. The president had a new car, and they got pulled over. Today, we would call it “pulled over for driving while Black.” They pulled him over, and were questioning him because he was in that new car. She said he kept saying, “Yes, sir. No, sir. Yes, sir.” You know, answering meekly because you don’t know what’s going to happen in those situations. And so, that was a rule. Get through the South before dark. That’s what our professors were telling us.

Now, here’s something that happened just last year. My sister had a man drive into the back of her car. He hit her. He was an older white gentleman. He hit her and drove off. So she’s following him and honking her horn, and he’s just going, ignoring her. She called me while it was happening. So, they finally got to a place where he had turned and pulled over. He was an older man, and he said he didn’t know what had happened. He said he couldn’t see well and had lost his wife, and I don’t think the man even had a license. And so, she called the police to have a report made. Well, about three or four police cars pulled up.

I’m still on the phone. The police pulled up and began yelling at her, and it was as hateful as could be. They were telling her that they didn’t believe he had backed into her car, that she already had that dent, and everything else. This man had admitted that he had backed into her. But they see the white man, they see this Black woman, and they hadn’t even gone to talk to the man. The man didn’t have insurance with him or anything else. So, is Jim Crow still with us? Laws change. Hearts don’t.

Were there colored and white signs in your town growing up?

There were. Everything was fully segregated. At the Black school, we would sing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the Negro National Anthem. We did it at one of the graduations, and the school board forbade us from singing it. So, we had to stop singing it in school. We fully had Jim Crow, and even after Jim Crow, we had Jim Crow. Still had poll taxes and a lot of other madness that went on.

Did your parents vote?

Oh, yeah. My sister and I were laughing about it not long ago. Because Daddy was a Republican and my mother was a Democrat.

Well, the Republicans used to be the Lincoln party!

Yeah, that’s exactly right. And you know, when Lincoln was assassinated, he was Union and his vice president was from the Confederacy. That’s why the South didn’t progress well, because they were slaves in every way except by name.

Yeah, I often wonder how things would be different if Lincoln hadn’t been assassinated before he was able to fully roll out his presidential plan.

I wonder the same thing. And, The Birth of a Nation? Was it Woodrow Wilson, you had the president of the United States praising the Ku Klux Klan. Woodrow Wilson was a Democrat, friend of the KKK, and racist. They had a private screening of The Birth of a Nation at the White House. He praised the Klu Klux Klan. And that was the president.

The same white woman who told me about Poletown told me there were people in the Klan that she loved. Obviously, she wouldn’t identify them. But you didn’t know who was in the Klan. There were policemen, public officials, elected officials, politicians … many of them were in the Klan.

Did you ever know of anybody who was lynched?

Not personally. And when I was a kid, if I heard something unpleasant like that, I would just kind of bury it as though it didn’t exist. So, I don’t know what’s down there subconsciously. But in my hometown, there were a group of sanitation workers. Most of them were white, and there was this one Black man who was a sanitation worker. He was killed. They claimed it was an accident, and that they didn’t realize he was back there, and he got chewed up with the trash and killed back there. And my sister said she was talking to this white woman, and the white woman said, “It’s shameful what they did to that man.” And then the white woman quickly shut up. And so my sister said that they killed him. On purpose. The story I heard on it was that they killed him. The white people in the town would have known what happened.

Were you ever afraid for your safety as a young person?

In my segregated world, I was not afraid. There were generally no whites in our neighborhood unless it was like the milkman or someone. But the only time I felt fear in my neighborhood was one time I was walking from the store, and this white stranger was driving on that street. He said something really, really nasty to me. And it scared the life out of me, and I ran like crazy. Ran home. And my sister said, “You should have got his car tag.” And Mom said, “No, baby, you should have done just what you did.” Because he could have tried anything.

When I was in college, a group of us went to Houston, Texas, and we ended up in a restaurant. There were some white people who kept shaking our table and doing things like that. This was the early ’70s. Now, that was one time I was terrified. But some of the guys, the students I was with, they weren’t taking it. Some of them were from the Northeast, and they weren’t going to take it. They would have shot. If anything had happened, they would have done something. And I was terrified. I was thinking, my mama and daddy didn’t send me to college to go off to Houston and get shot.

But they insisted on staying. And so we ate, but I didn’t enjoy my meal because I was afraid. But the others I was with, they weren’t afraid. They were used to confronting directly like that. And the white people were saying derogatory things, but when the guys in our group showed that they weren’t taking it, they eventually shut up.

I remember my ex-husband and I going to a little fast food place to get some food, and I was sitting in the car while he got the food. And there were some white men in a car next to me, and they looked at me and started saying all kinds of racial, ugly things. And when my husband came out, I didn’t say a word because I didn’t want to have any stuff up in there. I recognized that I wasn’t the issue, they were the issue, they had bitterness and hate in them. And I wasn’t going to put myself at risk because of somebody’s bitterness within.

I still think it’s amazing that your family owned so much land as Black people at that time.

Yeah, it was by God’s grace, and was by my dad’s hard work. But you know, what I do remember is that my dad was always concerned about someone misplacing the deed. He was older then, and he was just really disturbed in his spirit about misplacing the deed, and that the white folk might try to take his land. Yeah.

There were other Black landowners in my dad’s age group. I was just thinking about the Hills. They had land not very far from us. Anita Hill’s family. My younger sisters and brothers were in school with her. And at that time, Oklahoma was only about 6 percent Black. Was it racist like other places? Yes.

How did you end up going into the law?

Oh, a friend wanted to attend law school, and I thought it was a neat little idea. So, I went. That’s pretty much the long and short of it!

My initial plan was to be a math teacher, and after I graduated from college, I ended up working at a bank. I supervised tellers and new account representatives in a small town in Oklahoma.

Then, right out of law school, I worked for the federal government in Washington, DC. After that, I worked for the federal government in Fort Worth, Texas, because my parents were getting older and I wanted to get back near the Texas-Oklahoma area. I worked in the state government in Texas after I left the federal government, and then I’ve done some private practice. I’ve kind of run the gamut of all of it. Yeah. Then, I retired for the ministry. I went to seminary in Dallas. And now, I teach conflict resolution and racial reconciliation at two Bible colleges here in Texas, and I also run a business.

When I worked for the state of Texas, we had one Black supervisor. My nephew would cut his yard; he had a beautiful home. His wife was a doctor, and his home almost looked like a mansion. And I asked him, “Why do you drive this old truck to work? You got all those fine cars and your big home.” He said, “Oletha, if I drove this car to work, white people would try to take me down. They’re not gonna let you get ahead or try to do better than them. And that’s why I drive this truck.”

Now, there was another lady who worked a menial job. And they had no reason to fire her. But she was able to go out and buy a new car, after working. Well, they fired her. She bought the car and they fired her, and they said to her, “We don’t know how you going to pay for that new car you got.” Yep. “We don’t know how you going to pay for that new car you got.”

You know, there’s hate in the world. But if you get hatred in your heart, then evil wins. You’ve got to put it in perspective and recognize that they don’t know who they are. And they don’t know who you are. My father would always ask me, “What makes one man think he’s better than another man?” And I’d say, “Well, he’s not, Daddy. He’s not.” And that answer always satisfied him. And so, instead of telling me stories about what happened to them, they were instilling in me that nobody is better than me. They wanted a better life for us than what they had, and they made sure we knew that there was nobody better than us.

Were you involved in the Civil Rights Movement?

No. Of course, we did have … you know in 1968 we had the marches and all the things. And I saw on TV, the water hoses being turned on people, the dogs being turned on people, John Lewis, Bloody Sunday, the Freedom Riders, all of that. But I was a little country girl from Okmulgee, Oklahoma. However, God didn’t call everybody for civil activism in the same way. One of the things I do now is teach peace and reconciliation. So am I doing it? Yeah. Not just for Blacks but also for whites, because they don’t know what they don’t know.

I can remember I was in school one day, and a guy who was kind of a class clown came in and told my teacher, “Ms. Hayes, Dr. King was assassinated.” And she said, “Don’t say things like that!” She thought he was playing around. But it turned out to be true. And I remember everybody was glued to the TV. I was a senior in high school. Obviously, there was much talk about it, much solemnity about it. At church, everybody was grieved about it.

Did y’all get any of the Black newspapers?

Yeah, The Oklahoma Eagle. It was out of Tulsa. The Oklahoma Eagle, and every Black household got it. We had the Black church that kept the community connected. We had our Black newspapers that kept us connected. And even during slave time, it was the Black churches that kept even the slaves connected. And then they would talk about some of the old songs like “Steal Away to Jesus.” The slaves would be singing, and that was a sign for them to say, “We’re going to have our church meeting in the swamps tonight.” And there was “Couldn’t Hear Nobody Praying” to let them know that it was successful and the master didn’t even know they were out. It’s creative genius.

But God did not make any lesser people, period. I’m a strong Christian, and my intent in sharing this is to say that there is great evil that has been perpetrated against Black people. But you also had white abolitionists, and Quakers. So it’s not all evil. My point is not to attack anyone, but just point to the truth. And a lot of the stuff that they’re saying, and have said throughout history, is not true. I mean, you have Michelle Obama being drawn as—compared to—a monkey by some white people. That’s been passed down. All that is still with us, it’s been passed down.

This is my belief on it. The Bible says that Abel’s blood cried to God from the ground. You think that the blood of all of those slaves who were thrown over the ship, or were hung, or the Martin Luther Kings and the Medgar Evers, you name it. Their blood cries to God. George Floyd’s blood cries to God from the ground. But there is a change. Because never before would you have ever seen everybody marching with Blacks during that shutdown based on George Floyd’s killing. So God is doing a shifting.

There’s a huge evil connected with race in this country. And so, we’re imploding from within. That’s my position. We’re imploding from within because of sin.

What was it like when things became integrated?

Well, I’m Black, and I had a great childhood, and I love being Black. And so, I’m going to show you where integration was not necessarily a great part of my life. My elementary school was Black, my high school was Black. My college, Langston University, was predominantly Black. The first time I went to a predominantly white school, I was in my fifties, when I went to seminary school here in Dallas, Texas. Dallas Theological Seminary.

So here I am, coming out of a Black college, ended up working at a bank in Oklahoma and there were racists there. But I had to move on and bury it because I wasn’t much in a position to say or do anything, and we didn’t really have the civil rights laws to the extent that they were actionable at that time. I didn’t even really know what my rights were for the most part. So trying to work in that environment was tough.

When I was in high school, we had to go compete with some other schools on some things. And so, they put our little school up against some really big schools. And our teachers said that they did that to keep us from winning, because we would have taken it away. Our teachers had really prepared us! But we were being put up against schools with hundreds of kids, and we were small. And our teachers wrote and told them that they put their students with the wrong group. And they wrote back and said, “We reserve the right to put you where we want to put you.” That’s the school system saying that. The educational system in Oklahoma. They told us they would put us where they wanted to put us.

Near my hometown, there was a white Christian church, and one summer, they decided that they were going to let some of the little Black kids go to their camp. That was my first real experience with race. I was about 12 years old. And they were not kind. The white kids were not kind to us at all. And if I had left there, and hadn’t met one little white girl who was nice, I would have thought all white people were like that. She lived in the same town as we did, and she was nice. And she wanted my address. In our little town, we probably lived 10 minutes walking distance from each other, but we wrote letters. You know, Black part of town, white part of town, never the two should meet. So even though we lived close to each other, we wrote letters.

Sixty years later, I get this ping on Facebook Messenger, and it’s her. She’d been looking for me for years, and we reconnected. Then later on, I was kind of disappointed after I saw something that she had said about the protests connected with George Floyd. It was just kind of sad to me that she didn’t grow up to be who she appeared to be when she was a child.

When I was in seminary school, and Obama was elected, one of my professors said, “Well, at least maybe Obama can get the boys to pull up their pants.” I heard it mentioned that there was another professor who said to some young Black students, “Settle down and quit acting like some little monkeys that just got off the boat from Africa.” And then there was another professor in seminary who, after the police had stopped his child, said, “My son has blond hair and blue eyes. Why would the police stop somebody like that!” It did give me pause, but I just moved on, because I’m used to it.

I don’t want to give the impression that I don’t stand up for my rights, because I pretty much always have. Because I do … I’ve had to confront racism. And I have done that. But I admire the younger generation. You all are tough. If something is racially insensitive or culturally insensitive, you will call it out. And that’s a good thing.

It’s because we are privileged to live in a time where we can be more bold, because of previous generations working to make things better for us. Do you think Dr. King’s dream is possible in this country?

(Very long pause.)

I think that it is possible to a degree. And I think the younger generation will do much better with it than we will. There are some in our generation, Black and white, who I think have the right heart and mindset. But I think the younger generation will do better.

I see things getting better down the line, but in order for them to get better, we had to be where we are now. For this thing to have surfaced to the degree it has surfaced, it was there. It’s kind of like the iceberg: you’re seeing the tip, but that thing was deeper. The iceberg of racism is underneath, and if you don’t know it’s there, you won’t be able to fix it.

Regarding integration, it had to be done to some degree. You couldn’t sit there and not do it. You couldn’t sit there and not do your Selma march and not fight for your rights. Dr. King did it for his season in his time and for his generation. The Freedom Riders, the counter sit-ins, the Bloody Sundays, it had to be done. We’ve paid a cost for freedom. And we continue to.

Those who have a heart of racial division and strife and separation and racism, that’s evil. We have two countries. It still goes back to the love of the Confederacy, and then those of the Union. That’s why they say, “Away in Dixie,” and why we ended up with all those huge monuments to the Confederate soldiers. In the United States, the heart for what we believe didn’t change. Those who believe in racism still do. Those who believe in equality still do.

This is not just history, because the baggage of it is still with us. A white woman once asked me, “Do you always feel Black?” Well, that’s all I know! I’m Black. That’s all I know. But when I had that situation with the U-turn in Maryland, and I realized what I had done, I thought that if you can “feel Black” in a particular context, that moment would have been it.

Learn about history, but don’t become bitter about it. Take the creative genius that God gave you, and make the world a better place. Don’t become bitter. Become better.