TV and film writer; Paris Match and Life magazine photographer

(1937– )

People don’t realize that the Bronx is so hilly, especially where we lived in the Macombs Road area. There was a huge flight of steps going up from the street below to Davidson Avenue, where the entrance to our building was. Our apartment was on the first floor facing the back so because of the hill we were at eye level with the Jerome Avenue el. I was watching the trains go by when I was about five years old. What I saw were subway cars filled with men in uniform. When I asked my mother who they were, she said, “They’re soldiers going off to war.” I couldn’t fully understand this at the time, but she said it with a lot of sadness in her voice. When the war ended in August of 1945, we were away on my bubbe and zayde’s farm in Winsted, Connecticut. My mother told me and my cousins to go up and down the country road so that we could bang on pots and pans with a spoon to announce that the war was over. I was eight years old at the time.

In the Bronx your neighborhood was also like a small town. You didn’t leave it. If you went downtown, you were going into the city—Manhattan. Or summers you might be lucky enough to go to “the country,” usually meaning someplace in the Catskill Mountains, or in our case my grandparents’ rural cottages, where you were surrounded by the same people. Since my neighborhood was like this small town, I was provincial in my outlook. I was this naive kid. Maybe it was just in our family, but for instance we didn’t listen to music in the house even though I took accordion lessons. We didn’t even listen to music on the radio. We listened to comedy shows.

There was no library in our house. We had a set of classics but they were never opened. When I finally started writing, I went from illiteracy to writer overnight. And as for my being a photographer, I didn’t want words. Words were the enemy. I was uncultured in an uncultured world as far as my eye could see. Even my friends didn’t talk about books and reading. I had to read for school but I never liked it. Thankfully in high school there were lots of different kids from all over the city. I found out that the whole world wasn’t brought up the way I was. I went to the High School of Industrial Arts. I could draw. I think I got in because my older brother went to that same school. He was a very good artist. They’d always ask me, “Are you related to Mel Rapoport?”

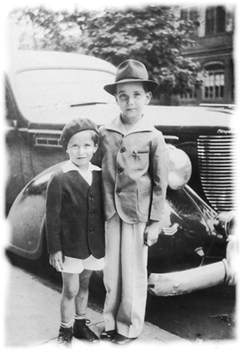

I had this love/hate thing for my brother. And I definitely wanted his approval so often I’d play dumb so as not to compete with him. I was the good kid and he was the boss over me. My parents would leave us alone without a babysitter. They said that if there was ever a problem to just call the super. My brother and I were jumping from bed to bed and one of the beds collapsed. So we called the super and he jerry-rigged it. When my parents came home, my father figured it all out—and my brother got blamed. My father hit him with a belt. My brother was about nine years old at the time. I was six. He was humiliated and scared and hurt and he hated me for it. My reaction was don’t get into trouble. I steered away from pushing those buttons, but my brother wasn’t so lucky. Maybe he had ADD, which wasn’t diagnosed in those days.

When I went away to college in Ohio I was still kind of naive. If you grew up Jewish anywhere in New York, you were still a New Yorker. Jews from Cleveland were different. They had their own midwestern shtick. It was culture shock going away to college. The students drank. In my house while growing up there was no drinking. There was no such thing as social drinking. We had cream sodas or milkshakes. I thank my parents for that.

Although I was naive and didn’t know about the world, I did have some street smarts. When I was still in the neighborhood, some of the kids got together to form a gang. We had taken an oath where we swore to protect each other. The threat was mostly from the Irish kids in the neighborhood, especially at Easter. That was the brown-shoe, black-shoe period. The Irish Catholics wore black shoes, and when you saw that you knew right away that you were in trouble. They weren’t killers or anything like that. It was mainly humiliation. You ran when you saw them, but sometimes you were cornered. You were made to sing or dance. You couldn’t escape it. Sing the National Anthem, or Say the Pledge of Allegiance. You were stuck there and they’d laugh. We figured out that we had to travel in groups, calling out so other kids in your gang would come running. Sometimes there were fistfights, and eventually adults would break them up. Both sides would split if cop cars came.

Those street smarts got me through a lot of different situations. I basically felt I could manage and survive in the real world.

When I was working for Paris Match I was sent to photograph Marilyn Monroe, who was going to leave Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. There were three of us from the same magazine. I was standing with them and thirty or forty other photographers so I decided to go to the apartment building across the street for a unique angle. I went to the third floor and rang the doorbell. A little old Jewish lady went to the inside of her door. “Who’s there?” I explained who I was and that someone was coming out of the hospital any minute and that I had to photograph her.

“Who’s coming out of the hospital?”

“Marilyn Monroe.” Ching, ching. The door locks opened. I was let in. I went to the opened window and put my arms on the windowsill. I had the Bronx chutzpah to ask, “Do you have a pillow I can lean on?”

I took a series of pictures that really told the story of what Marilyn Monroe was like, with all of these people surrounding her. She had been followed out by at least a dozen and a half people. She stood on the street near the curb, talking to the radio and TV guys—she never stopped posing—and I got a series of pictures different than anyone else. The problem was, they didn’t use any of my pictures. You have my permission to use this one.