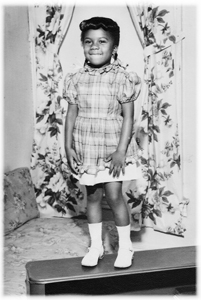

Writer/children’s book author specializing in African American themes

(1942– )

All of the action in our world took place on the stoop. It was our town square. We played dolls and jacks there and jumped double Dutch in front of the stoop. The stoop was also the place for news and gossip, which was mostly done by the adults and older girls. Those of us who were younger had no news or gossip. Only lies or stories we told, just to have something to say too. There was one neighbor who, when I think about it now, must’ve known everything about us. I can see her sitting in her third-floor window, with her arms folded, leaning on the pillow she kept on the windowsill. She sat at that window morning, noon, and night, in all seasons. She was the neighborhood watch before that term was ever used.

I don’t know anything about the West Bronx, Jerome Avenue, over there. We rarely traveled to that section of the Bronx. That was like another country. We lived farther east and north in the Morrisania area. I think in the early fifties, when I realized what was going on in the world, when I was about ten, that’s when drugs started coming in. We never felt threatened, though. It’s very interesting. Back in those days, you didn’t hear about women being attacked on the street or old people being held up. You didn’t have that. We lived in a tenement, 919 Eagle Avenue. There were also some private houses down the street, little private houses. One family—I remember them so clearly because they were doing so well—they had a house and they had a store.

Our neighborhood was primarily African American. There were a few, but very few, whites. Most of the whites had moved but there were two little girlfriends that I had, Patsy and Barbara. I guess they were the last two white children left in the neighborhood, and they just blended. They played with us all the time.

But though you had African American families of different economic levels, we were all in the same place. There was a musician who I’d see with his horn in a bag, going to work. There were a couple of nurses. There were some older kids who were going on to college. Then we had some very poor families. In our building there was a great mix. I guess to outsiders, all of us were poor, but although my family didn’t have a lot of material things, my mother and my father created a safe environment for us right in that apartment.

My mother read to me before my two younger brothers were born, which was before I could read on my own. Reading on my own was a big wish of mine. I’d beg her for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which she read to me over and over. She’d do that no matter how many times I asked, but in later years she confessed that she didn’t like that story at all and couldn’t understand my fascination with it.

My father had his own business. A photo studio in Harlem. When we were young, we had no idea of the years he’d spent, even before we were born, documenting cultural and historical events there. He had taken pictures of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and many other big bands, along with other famous people such as Mary McLeod Bethune, Eleanor Roosevelt, Mayor La Guardia, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and so many others. He also took pictures of confirmations, baptisms, weddings, and many street scenes with ordinary folks, and always took pictures of us so that he didn’t waste any unused film. He documented our lives too.

My mother worked off and on, but she mostly worked in factories. And like I said, she tried to create a good environment for us. So we didn’t know how poor we were, materially.

As far as I knew, all the men in our neighborhood had jobs then, and there was a man, a father, in every household. You hear so much about these African American families, especially now, with the stigma that there’s no man in the household. There are only single women. It wasn’t like that when we were growing up. The men could get jobs and the families were together. They may not have been the best jobs or the highest-paying jobs, but they all worked. And if you were on home relief, as they called it then, that was a shame. You didn’t even talk about it.

Our next-door neighbor, who was also the super of the building, was the first person in our tenement to own a television. My brother Victor and I, along with the super’s grandsons, spent as much time as we could watching, but we were only allowed to stay for one program, the Howdy Doody show. My mother kept a check on us and warned us about wearing out our welcome. It was a happy day for us kids when my father finally bought a TV set. I watched the Mickey Mouse Club, my favorite, every day. Though back in those days there were no black kids in the club I related to Annette Funicello, who stood out from the others.

Like everything else, the TV set wore out, but you didn’t get a new television just because the old one was broken. Things got fixed or patched up or you improvised. My brothers and I improvised. We took turns standing behind the TV, holding the antenna to keep the picture going. We’d tell the person holding the antenna what was happening, but when it was time to switch, whoever’s turn it was, that person invariably whined about the length of time spent behind the TV instead of in front of it.

Our parents weren’t involved in this craziness. Neither had time to watch television. This is just what we had to do if we wanted to watch. One of my grandmothers lived with us. We came home for lunch when we were in elementary school, and if my mother wasn’t home my grandmother would be there, looking at the television. She loved Liberace. Oh how she loved Liberace! But she would be there for us.

I had a happy childhood, yet when the drugs started seeping in, I remember someone was hurt in the hallway. She was a junkie and she was shot. That’s when my father made the decision. “Okay. It’s time. We gotta get out of here.” I was fourteen. That’s when we moved to a house he bought on Belmont Avenue.

We left the old neighborhood, and then the world changed for me. When I entered Theodore Roosevelt High School, it was at the beginning of an influx of African American and Latino children from various parts of the Bronx. The lunchroom was segregated with all of the black students sitting together at two or three tables. Some of the teachers didn’t seem to like us much either. I can remember a few teachers who were superb and who didn’t seem to care who we were, as long as we learned. Not all of them were like the teacher who counseled college-bound kids. When I went to his office, I was told that college was for smart kids. I can’t even remember how I responded. I think that I probably believed him for a moment, but I still had my books, and by that time a dream. I wanted to be a writer. High school, where I discovered Langston Hughes and even wrote horrible poems imitating him, was the beginning of my journey. I ignored the school counselor and took college courses at night while working as a secretary during the day.

My mother’s love of books and writing and my father’s love of history and telling stories through his photographs influenced me, but dreams have to be supported. I continued taking night courses and worked during the day until I received a bachelor’s degree in English literature. What does a person who wants to be a writer do with a degree in English literature? You become an English teacher. But as the saying goes, “Man proposes and God disposes.” I discovered that teaching reading and language arts to middle-school and special education high school youngsters was what, in the end, I was supposed to be doing. I wrote and published seven books while I was still teaching, but I thought of myself as a teacher first and foremost. My last teaching assignment before retirement was in a middle school in Morrisania in the same neighborhood I grew up in. I had come full circle.