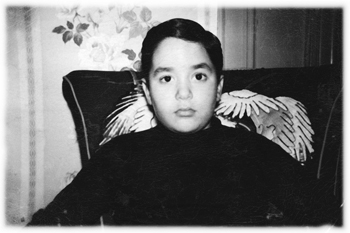

Artist/illustrator, writer

(1943– )

There was this full-city-block empty lot across the street from our building. It was filled with gravel, broken bits of glass, sharp pebbles, crabgrass, stunted trees, and mounds of garbage. And we played there day and night. We played in that lot because we were told it was safer than playing in the street. “Because of the cars,” my father said. And you’d look up and down the block and there’d be maybe six cars parked on the entire block because this was the forties and nobody had cars. And I said to him, “What was it like when you were a kid? You told me you played in the street all the time.” And he said, “Well, yeah, we didn’t have to watch out for cars because there were no cars when I was a boy growing up on the Lower East Side, but you had to watch out for horse shit because the streets were filled with it.” And I said, “Well, that must’ve been awful.” He said, “I don’t know. It made sliding into second base pretty easy.”

On the corner in our old neighborhood there was a bank. Manufacturers Trust bank. And right next to it was a New York public library. We played stickball for hours against the wall of that library. You could hit a rubber ball easily three times the distance you could hit a softball. And the speed of it! I once hit a line drive and it went into a city bus. Through a window of a moving city bus! I held my head in my hands. It wasn’t that I worried I might have fractured somebody’s skull with a hard-hit ball. I was worried that I lost the ball because it went into the bus. It all happened in a split second, but the bus kept moving, and then I saw there was the ball on the other side, bouncing in the street. It had gone through the opposite open window of that bus. What are the odds of that happening? The driver didn’t even slow down. It may have happened so fast that nobody in the bus even noticed that this ball flew through the windows.

These are the things that make childhood so remarkable. Something like that stays with you all these years. Let’s see, Jefferson had on his gravestone that he was the author of the Declaration of Independence, that he was the writer of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom and the father of the University of Virginia. Will mine say that I hit a ball through a Number 3 bus and it came out the other side?

There was a particular look to the Bronx. The look of the architecture and the streets. The feel of being under the el and the light coming through. I didn’t know Berenice Abbott had already made the photograph that was in my own memory. The light coming through under the el used to mesmerize me. I would walk with my mother and she’d go into a store and I’d stand in the street and I’d look at the light filtering through. Beautiful sunlight. Through the tracks.

If your childhood was a happy one, that becomes a place that has magic to it. And that was our Bronx in those days. We felt no threat. The war was over. And we were alive and there was a sense of real possibility. Possibility. There was a world opening before me. I didn’t know what I was going to do with myself, but I didn’t dwell on that too much. I knew I was going to draw and read and go to college.

There was another thing. There was a smell. It’s hard to describe. The smell of a thunderstorm. The change in the barometer as the sky would turn a kind of a deep gray-green and the summer thunderstorm would come over and the dust would lift from the street. It was like the rain or the falling barometer actually drew this stuff out of the ground into the air. You’d breathe it in. You could smell the storm. The aftermath of it was clean. The Bronx was an extraordinary and fertile land to grow up in.

My father once explained to me the difference between a Bronx accent and a Brooklyn accent, ’cause I had said, “I don’t get it, what’s the difference?” And he said, “In Brooklyn, they would say ‘I’m gonna moider da bum.’ In the Bronx, they would say, ‘I’m gonna muhdah da bum.’ There’s a lot of ‘duh’ in it.” My father would then say, “Either way, the guy’s dead.”

Before television, men and women went outside at night from spring to fall to sit on beach chairs, or whatever chair they brought out, in front of the building. The women talked, the kids played, and the men smoked cigars and belched. It was after dinner and everybody came out, and that was the sound track of my early days. If a fight or a baseball game was on the radio inside someone’s apartment, that person would open the windows so everybody outside could stand around and listen. Things changed when television came around and families went inside to watch TV. They didn’t go outside anymore. And you had air-conditioning, so you didn’t have to go outside to cool off. Suddenly you didn’t know your neighbors. The world began to evaporate for us. The reason it seems so magical in my memory is that it’s a world that’s gone.

In his acceptance speech at the 1968 Republican Convention, Richard Nixon recalled that when he was a child, he would lay in bed in Yorba Linda, California, hearing the frequent rumble of freight trains as they passed through town during the night. He wondered where those trains were going, and if he got on one, where it would take him in his life.

Nixon and I had similar experiences. Drowsing in my bed half a block from the Westchester Avenue el, I would fall asleep while listening to the passing trains every night. But unlike Nixon, I didn’t wonder about the final destination of those trains. Where they were going was no mystery. On a Saturday afternoon that train would take me two stops east to Parkchester, where the admission to the Circle Theater was 25 cents. And I could buy an insane amount of candy, and watch two movies and ten cartoons.