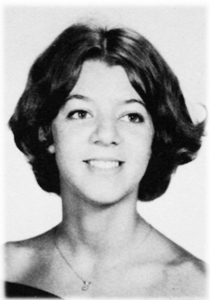

Artist/illustrator, author

(1949– )

When I was fourteen or fifteen and someone asked where I was from, I would say I was a Bronx Bagel. I liked the alliteration, I guess, but I was a complete Riverdale snob. I think that’s because we were so close to Manhattan and to Lord & Taylor and the Bird Cage, the store’s restaurant. We also had a certain pride in being in this little enclave. For me, it was really like an enchanted land. Riverdale was Oz in a funny way. Well, we did also go to other places in the Bronx. Loehmann’s was Mecca. Literally Mecca. We also went to Stella D’Oro. That was my first experience with nonkosher food. I had a shrimp cocktail and I heard the angels singing.

My father’s whole family was killed in the Holocaust. There I was living in Riverdale and the lullaby is, “Never again,” coming from him in a most poignant and powerful way. He constantly told us stories about his family perishing. And that he went to Israel in 1939, joined the underground, and fought the British. My mother went there in 1932.

The people who built Israel had a tremendous sense of “We did something quite extraordinary, both by leaving our old lands and by coming to this new country.” So part of the pride that I had was clearly instilled in me by my father and my mother too. Another story that’s in my soul—one where my sister really thinks I’m insane—but to this day, to help me meet a deadline, I say, “What if the Nazis came, in, say, two hours, could I finish the work? If they were coming in, like, eighteen minutes, could I finish the work?” So somehow I use the danger of them coming into my safe place on Twelfth Street to help me with an illustration assignment. I do that all the time.

My parents were not the happiest couple. There was a lot of silence and distance. My father was a diamond dealer and would be gone half the year. He’d go to Belgium for diamonds. He’d go to Israel. He’d do whatever he was doing on his own, having a good time and wanting to be a player in a larger field. He was not interested in being at home. My mother never complained about him. There was just a tacit silence. He was gone, and we were doing our thing. And we had a lovely time. When I think about it, I think that his being gone was a relief from the tension. I don’t mean to imply that it was some kind of horrific household. Everything from the outside seemed quite reasonable.

Because of my father’s business as a diamond dealer, all these interesting characters from around the world would visit us. It was a small club in a way. They seemed very eccentric, but they were people who traveled the world, who dealt in these luxuries, in diamonds and jewels. They traveled well, they dressed well, they lived well. They also divorced frequently. It’s so odd. My parents didn’t have a good relationship, but they were very social and entertained a lot. They had a big circle of friends. There was a big crowd of other Israelis who were either stationed in New York for something or here on business. And there were relatives.

My mother opened up the world of culture to me. I had piano lessons with Mrs. Danziger and ballet lessons from Miss Nubert. My mother took me to the public library, and we read the books from A to Z. And every Sunday night we had Chinese food at Bo Sun. We became part of this cultural community in Riverdale. That’s one of the reasons I went to the High School of Music and Art, because I was a pianist. My mother never was forceful in saying, “You have to be something or you had to be ambitious.” It was just, “Here it is and do whatever you want with it.”

It was wonderful that my mother allowed me to daydream—and the daydreaming allowed me to become partially the person that I am. There was no sense of needing to analyze anything or understand anything. I just kind of lived.

I spent a lot of time reading in the park that has a huge statue of Henry Hudson in it. I had the time to develop, on my own, a sense of language and love of language and love of the word. Coming to America from Israel and learning a new language at the age of four was wonderful. And the fifties were an optimistic time. When I got older and I started writing more seriously, I thought, Ugh, this writing is terrible. All that imagery! I thought that there’s a way to express what I’m thinking in another way and I have to express myself. That was a given. There was no question like, “Well, what else would I do?” Saul Steinberg had a huge show at the time. And since I read a lot, I had looked at a lot of children’s books. I looked at images and I looked at writing and said, “Wait a minute. There’s something going on here.” Combining images and writing looked like it could be fun. The word “fun” was really important to me. I had felt like this tortured writer with angst—this adolescent with angst. I just wanted to have fun.

I’ve had occasion to go back to my old lobby in Riverdale to photograph the plants that are there now and to see the views, both interior and exterior. And to go back to Mother’s Bakery, where we used to buy our mocha cream cakes. When I did those things, I connected to moments of joy, pleasure, and self-confidence. A sense of well-being.