Naturalist, businessman

(1991– )

When I was in middle school I was seen as a bit of a troublemaker, doing things against the rules, like finding ways to go outside to look for snakes, and talking when I shouldn’t have been. Maybe teachers picked on me a little because of that. My father worked for the Parks Department and there was one teacher who he helped out when a tree fell on her house in a storm. From that point on, things in school changed for me, for the better. I could see that someone was looking out for me. Someone was there smiling, saying, “Hey…” There was a changed attitude. That teacher would tell others, “Oh, that’s Erik. He’s okay. You can leave him alone.” My father’s job not only helped me out in school, it also sparked my early interests.

From the time I was three or four years old, I was interested in snakes and animals and nature in general, so I read books and watched as many movies on those subjects as I could. I was very passionate about them. I didn’t have friends that shared my interests but I had friends I’d kind of bring along when I looked for things like giant snakes or snapping turtles or lizards. When I was nine years old, I started going to Pelham Bay Park, which is a surprisingly good place to look for things in the wild. My father would take me there because his coworkers told him about snakes in the area. It’s not easy finding them. Where are the nooks and crannies where snakes would hide? It’s never a dull moment and always gets your brain going. When there are woods and fields, they’re usually teeming with animals if you know how to look for them. My biggest awakening was seeing that a very urban community still had these possibilities.

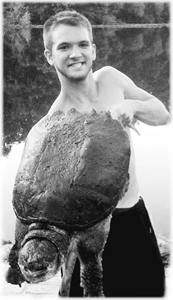

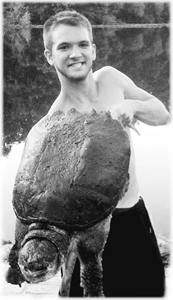

A few times, my father had mentioned that there were snapping turtles in the Bronx River. I had heard a lot of stories, like, Oh, we saw a six-foot snake down the street and this and that, so I was skeptical but I had to go look for myself. In Bronx Park, in the river, I’d go in the water, sometimes wading up to my chest or going under entirely. But I actually did find these snapping turtles. I’m talking about fifty pounds. Three feet from head to tail. Turtles you might find in Africa and South America. What also amazed me about the Bronx River was that it was crystal clear. Unless it had just recently rained, which would muddy it up, it was crystal clear. So beautiful. It was like a secret I had discovered. The whole experience there was like opening presents when you’re not sure what the present will be, whether it’s going to be something you really want or nothing. Seeing and finding these giant turtles in the river is a present I’ll never forget.

When I was at Bronx Science, I did a research project about the turtles, so during that time I actually caught about three hundred and twenty-five individual snapping turtles. I was able to trap each turtle where it lived and give every turtle a number on its shell. I measured them and weighed them and I discovered that there were about seven hundred snapping turtles living in the Bronx. Some discoveries I made were very surprising. The turtles in the Bronx grow larger than the ones upstate. Usually when a pond gets too crowded, turtles leave and go find another pond. Here, in the river, they can’t do that. After decades of being in that situation, only the biggest survive. I’d commonly find turtles that were just a few inches shy of the world record. I found some of the densest populations of snapping turtles that were ever recorded anywhere in the world—in the Bronx. I also found that there was a disease that they were getting, that hadn’t been recorded anywhere else. Part of their faces were being eaten away by bacteria or very serious diseases. Some of the snapping turtles were able to live to between thirty and fifty years old, which shows how tough these animals are.

After high school, I went to the University of Kansas because that’s the place to study reptiles. I only went there for one year, but while I was in Kansas, the Bronx accent stood out tremendously, of course. It was really funny, because I kind of got celebrity status there. Like, people would call their friends. We got a kid from the Bronx over here. People wouldn’t believe it. I had some call me and put their little brother on the line. I just want to hear your accent.

In the final few weeks of being there, I was doing a research project with a professor, who oddly enough also came from the Bronx. During that time, I was bitten in an artery by a rattlesnake, and it turned out that I had developed an allergy to them. There was no antivenom in the local hospital, so they flew me by helicopter to the next biggest hospital, in Kansas City. My heart stopped. I had no pulse. No blood pressure. I had stopped breathing. My professor was there with me, and when I was partially gone I thought I heard his voice saying, Listen, kids from the Bronx don’t die in Kansas. That brought me back to life. By the time I got to Kansas City, I was in rough shape, but got through it.

In the hospital, I was a celebrity too. Not because I had a rattlesnake bite, but again because I was from the Bronx. Their image was of Fort Apache. Their reactions were mixed. Fifty percent trembled and with the other fifty percent there was the wow factor. When I got through that experience, it all came together for me. When I was younger, I had thoughts like: “Could I work and live in Australia? Or in Africa?” Everything happens for a reason. I thought of all the natural, unspoiled areas of the Bronx, and I knew that was the most important place for me to be. So I came back.