PUBLIC HEALTH IS a relative concept. Compared to the 1850s, and using life expectancy as a measure, the increase from around 47 years then, to around 79 years now, represents a remarkable improvement. Indeed, many of the previously endemic conditions such as cholera, typhoid and tuberculosis have been successfully reduced to levels that would have been unimaginable to our forbearers. All of this progress required the building of social housing, water and sewerage systems, the creation of the NHS and welfare state, the introduction of health and safety legislation, clean air acts and more. The health of a population is largely determined by the conditions of society: the economy, workplaces, housing, social security systems, culture and the environments in which we live.

Despite all of this progress, when the Scottish Parliament was reconvened in 1999, public health was a policy area that was rightly still the subject of substantial attention. Compared to other Western and Central European nations, Scottish life expectancy was (and remains) lower, and has improved more slowly (McCartney et al., 2012). Since the early 1980s, mortality rates for young adult men and women hardly improved at all, largely due to increases in suicide, alcohol and drug related deaths. Furthermore, inequalities in health, defined as the systematic differences seen across the population ranked by socio-economic position, are wider that much of Europe and are, on many measures, increasing (Eikemo and Mackenbach, 2012; Scottish Government, 2017).

In the early days of the Parliament, work by the Scottish Council Foundation and the Public Health Institute for Scotland (PHIS) identified that the higher mortality rates in Scotland compared to the rest of Britain were not only due to greater poverty and deprivation. Some 5,000 additional deaths a year were initially ‘unexplained’ as ‘excess mortality’ and (unhelpfully) as the ‘Scottish/ Glasgow Effect’. This led to a lot of silly reporting of the problem, perhaps best illustrated by an article in The Economist which suggested that it was ‘as if a toxic vapour was arising from the Clyde’.

Subsequent research has since clarified that this excess mortality is best explained by a toxic combination of policies over the second half of the 20th century. The deliberate enticement of industry out of Glasgow (in particular), and the movement and break-up of whole communities through selective migration into new towns and peripheral housing schemes, left our populations much more vulnerable than in comparable cities elsewhere. When the shift to ‘neo-liberal’ policies was introduced in the 1980s this led to negative health trends across the UK, but more pronounced in Scotland because of these vulnerabilities (Walsh et al., 2017). All of this, in combination with the well-recognised impact of socio-economic inequalities and poverty, was working through intermediate mechanisms including food, alcohol, drugs and tobacco. It has left Scotland with its comparably poor health statistics and wide health inequalities (Beeston et al., 2013).

Of course, any description of a population’s health should take a broad view to include mental health and well-being, as well as the ability of people to function within society. Scotland has led the world on the better measurement of population well-being, but the goal of improving and narrowing the inequalities in wellbeing remains challenging (Scottish Government, 2017).

The Scottish Parliament has proven itself to be a leader in many aspects of public health. It was one of the first countries to introduce a ban on smoking in enclosed public spaces, something which has been extensively evidenced to show substantial positive impacts on outcomes as diverse as heart attacks and asthma (Pell, 2008; Mackay, 2010). The recent introduction of a minimum unit price (MUP) for alcohol is a global first and, to the credit of the Parliament, has been introduced with the caveat that it is evaluated thoroughly. The approach of the Scottish Government to use a National Performance Framework (NPF) to identify the outcomes on which policy is intended to impact, and to link together the policies across areas which should make mutual contributions, is also a very welcome and innovative approach for government. This has legitimised and supported the public health workforce to engage with policy-makers across government in recognition that the health of populations is more a function of the society in which we live, than just the health services that we have access to.

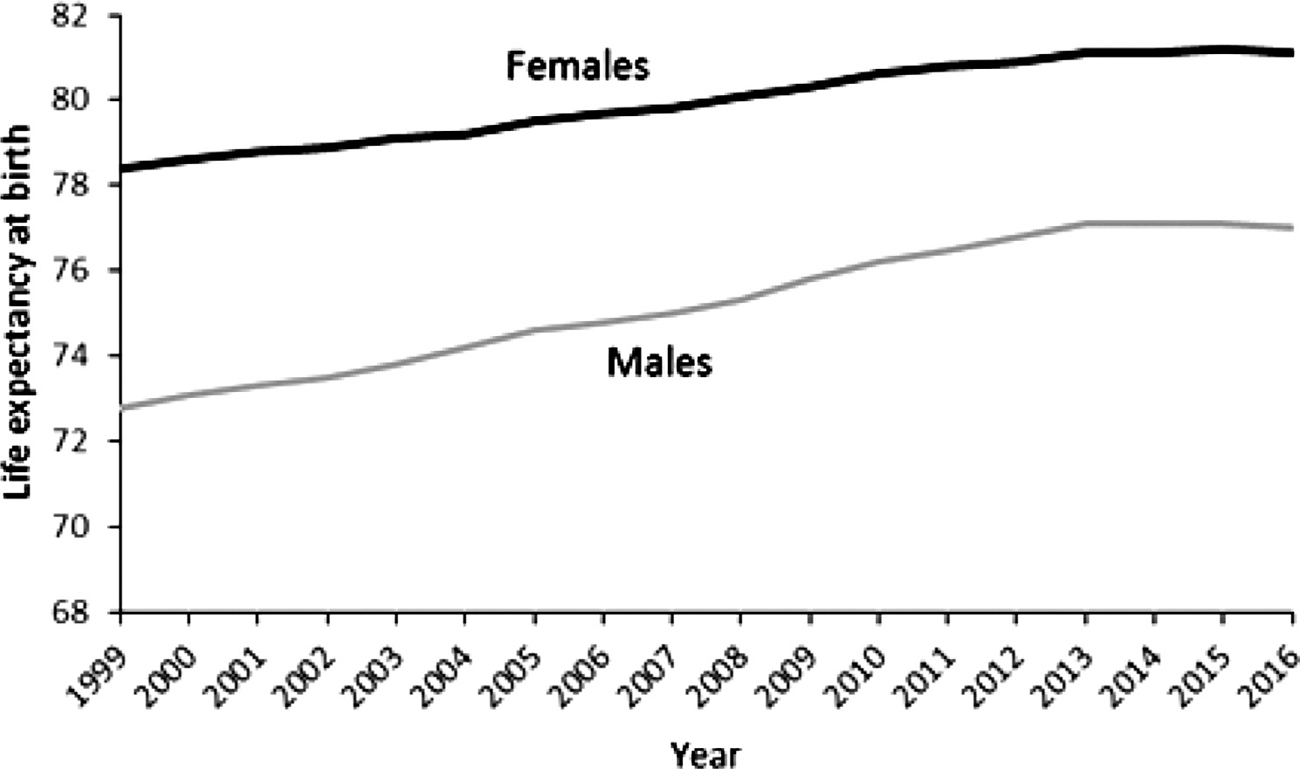

Despite these positive developments, many population health trends are much less positive. These include mental health, obesity, drug related deaths and, more recently, overall mortality. Life expectancy in Scotland, in common with the rest of the UK, the USA and some other parts of continental Europe (Ho, 2018), started to decrease around 2012 for the first time since 1945 (Figure 1). Various suggested causes have been proposed, including austerity and the associated cuts to local government spending; recurrent waves of influenza; reduced value and increased conditionality in the social security system; and the rise in obesity.

Figure 1 – Life Expectancy in Scotland, 2000–02 to 2015–17 (note shortened y-axis)

Source: National Records of Scotland.

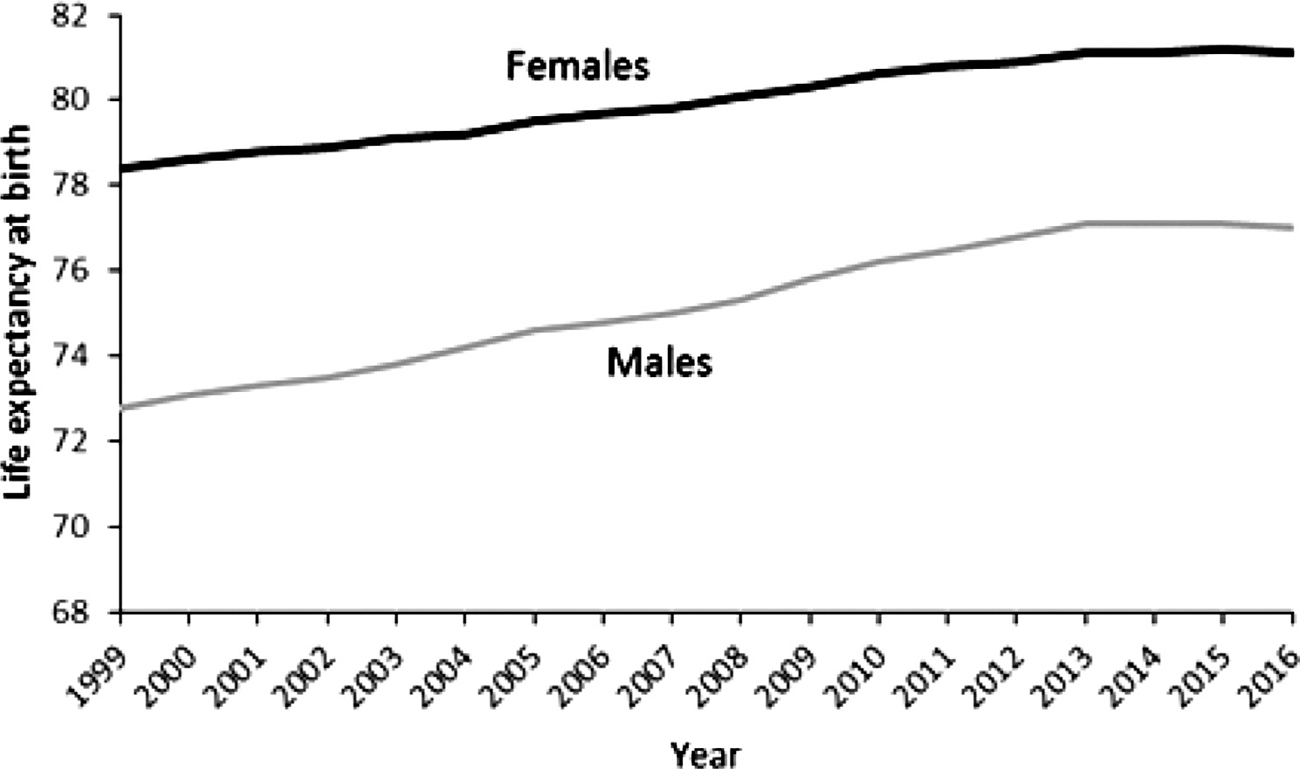

Inequalities in health, the systematic differences in health outcomes across the population ranked by socio-economic position, are very large in Scotland. Compared to rest of Europe, inequalities in mortality for women are the worst of all countries, and for men they are only better than countries in Eastern Europe. The premature mortality rate amongst those living in the most deprived 10 per cent of areas in Scotland is 825 per 100,000 per year, almost four times higher than the rate for those living in the least deprived 10 per cent of areas (Figure 2). The inequality does not only impact on the poorest communities, as there is a gradient across the entire population. Inequalities in health closely track trends in the fundamental causes of income, wealth and power inequality. As such, the inequalities that were high in the 1920s and 1930s, fell rapidly after the Second World War, during the period of welfare state building, to a low during the 1970s, before increasing rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s to the stark inequalities we see today (Beeston, 2013).

The most effective ways of reducing health inequalities is to reduce the inequalities in income, power and wealth in society. In general, policies that use regulation, taxation and legislation to make healthier products and activities easier or more affordable and unhealthier products and activities more difficult or expensive, are effective at reducing health inequalities. Good examples of such policies include legislation and pricing controls for alcohol and tobacco and subsidies for healthier foods and leisure activities (McCartney, 2013, Beeston, 2013).

Within Scotland, and in addition to the introduction of the ban on smoking in public places and the introduction of minimum unit pricing for alcohol, other policies have made a positive contribution. For example, the limited available powers to slightly reduce income inequality through the Scottish Income Tax powers. The Community Empowerment Act has also recognised the role that inequalities in power play in society and make a contribution to addressing some aspects of it. Perhaps the most important initiative to convene a ministerial group on health inequalities which recognized the importance of all policy domains in causing health inequalities and in reducing them. However, most policy which determines income, wealth and power distribution, such as most income tax and social security policy, is reserved to Westminster. This has created a tension where the Scottish Parliament is responsible for public health outcomes but many of the relevant powers are reserved. Indeed, the health consequences of changes to the social security system are now well recognised (Taulbut, 2018).

Figure 2 – Age-Standardised Mortality Rate (<75 years, Scotland 2016)

Source: Scottish Government.

The NHS, and more broadly the health and social care system in Scotland, is the single largest spending area for the Scottish Parliament. Parliamentary scrutiny and interest in the NHS are very high as the system evolves to cope with rising demands and technological innovation. The Christie Commission recommendations and the move towards partnership arrangements for primary healthcare and social care have marked a different direction for policy from much of the rest of the UK where privatization has been rapidly implemented. The full impact of the changes in Scotland have yet to be seen, but the intention is to reduce the potential for ‘cost-shifting’ between the NHS and local government and to promote genuinely more collaborative approaches which provide higher quality services with less institutional barriers. The extent to which funding has kept up with rising needs, the ability of the system to retain clear accountability and for resources to consistently be channelled into the most effective services has, however, meant that many health boards have struggled to consistently meet all of their financial and performance targets.

Scotland compares well internationally on most outcomes. However, for most markers of health, and in particular for health inequalities, it compares very poorly. The Scottish Parliament has played a very important role in facilitating innovative and effective policies to change this, but many challenges lie ahead. As Scotland strives to become an environmentally sustainable nation, and to change its economy accordingly, it will require to make a transition that supports health and equality. There are many health challenges arising from the nature of society today which remain to be adequately tackled including obesity, health inequalities and drug related deaths. The potential solutions to these health challenges may be similar to those broader societal ones: a more sustainable and healthier food system; planning for active travel to become the norm; a social security system that provides sufficient income for the whole population; and ways of sharing income and reducing consumption such as some forms of carbon rationing (McCartney 2008a, 2008b). The extent to which Scotland can act on these is variable, but the rest of the world now look to us as a source of innovation and inspiration and it may be that our influence can go beyond our own shores.

Beeston C., McCartney G., Ford J., et al. (2013), ‘Health Inequalities Policy Review for the Scottish Ministerial Task Force on Health Inequalities’, Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland.

Eikemo T.A. and Mackenbach J.P. (2012), ‘EURO GBD SE: The Potential for Reduction of Health Inequalities in Europe. Final Report’, Rotterdam: Erasmus University Medical Center.

Ho J.Y. and Hendi A.S. (2018), ‘Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries: retrospective observational study’, British Medical Journal, Vol. 362 No. k2562.

McCartney, G. and Hanlon, P. (2008a), ‘Climate change and rising energy costs: a threat but also an opportunity for a healthier future?’, Public Health, Vol. 122 No. 7 pp. 653–658.

McCartney G., Hanlon P. and Romanes F. (2008b), ‘Climate change and rising energy costs will change everything: a new mindset and action plan for 21st century public health’, Public Health, Vol. 122 No. 7 pp. 658-63.

McCartney G., Walsh D., Whyte B. and Collins C. (2012), ‘Has Scotland always been the ‘sick man’ of Europe? An observational study from 1855 to 2006’, European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 22 No. 6 pp. 756–60.

McCartney G., Collins C. and Mackenzie M. (2013), ‘What (or who) causes health inequalities: theories, evidence and implications?’ Health Policy, Vol. 13 No. 3 pp. 221-27.

Mackay D., Haw S., Ayres J.G., et al. (2010), ‘Smoke-free Legislation and Hospitalisations for Childhood Asthma’, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 363 pp. 1139–1145.

Pell J.P., Haw S., Cobbe S., et al. (2008), ‘Smoke-free legislation and hospitalisations for acute coronary syndrome’, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 359 pp. 482–91.

Scottish Government (2017), ‘Long-term Monitoring of Health Inequalities’, Edinburgh, available online at: https://www.gov.scot/Publications/2017/12/4517.

Taulbut M., Agbato D. and McCartney G. (2018), ‘Working and Hurting? Monitoring the Health and Health Inequalities Impacts of the Economic Downturn and Changes to the Social Security System’, Glasgow: NHS Health Scotland.

Walsh D., McCartney G., Collins C., et al. (2017), ‘History, politics and vulnerability: explaining excess mortality in Scotland and Glasgow’, Public Health, Vol. 151 pp. 1-12.