Chapter 25

It was snowing again, just like Granny had predicted. Tilly ran silently across the garden, picking her way across the grass and through the damp undergrowth.

Tilly let out a huge sigh of relief. Helen was waiting for her, huddled in their den. She was wrapped up warmly in her old-fashioned green woolen coat with the velvet collar and two rows of brown leather buttons, a long black skirt, lace-up boots.

Helen patted the ground next to her. She put her finger to her lips: “Sshh!”

Tilly wriggled inside the den and sat down.

Helen pulled the blanket over both their laps.

Tilly could see the trail of her own footprints, leading the way from the gate across the garden and another set of tracks, small and neat and closer together. “The fox?” she whispered.

Helen nodded. “Watch,” she whispered.

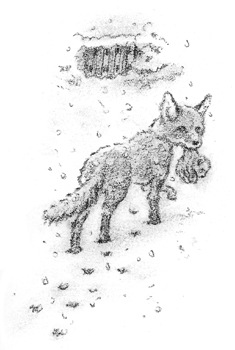

Tilly shivered. She heard something scrambling, and then a flurry of snow blurred her vision, but suddenly right in front of her was the fox, carrying a tiny cub by the scruff of its neck, in her mouth. She plodded through the snow to the gate and disappeared.

“What’s she doing? Where’s she taking it?”

“She’s moving the cubs somewhere else. Something must have frightened her. The garden isn’t safe anymore.”

It was painful, watching the vixen make her slow journeys with her babies in her mouth. Tilly wished she could help. Where was the male fox? It looked like such hard work, carrying the cubs like that, through the snow, in the dead of night, all by herself.

She made three journeys. They waited for her to come back a fourth time. But nothing happened; there was no sign of her. Just the cold creeping in, and the snow settling deeper. Even huddled under the blanket, close up to Helen, Tilly was freezing.

“Maybe there were only three,” Helen said. “That was the last one.”

“So tiny!” Tilly said. “Weren’t they? Will they survive?”

“I hope so,” Helen said. “I expect they are tougher than they look. Like human babies.”

“What if she’s forgotten one? Or something’s happened? Supposing she’s left one behind in the old den?”

“She might leave one if it was sick or too weak, the runt of the litter.” Helen said very matter-of-fact. “She has to do what’s best. There’s no point if it’s not going to survive.”

“Survival of the fittest? It’s horrible. I’m going to look. Just to make sure.”

Helen pulled her back. “Don’t be silly. If the vixen does come back and sees you, she’ll abandon the cub anyway, because you’re there. And if the cub’s too tiny and weak, what can you do?”

“I can try and save it.”

“How? You can’t give it what it needs. You can’t keep a fox as a pet. That’s cruel.”

Tilly remembered a story Mom had read her once, about a girl and a baby piglet who was going to be killed because it was the runt of the litter. The girl, Fern, saved the piglet and looked after it. She fed it milk from a baby’s bottle. But that was a piglet, not a wild fox cub.

“I’ve got to go back now,” Helen said. “And this is the last time I can come and see you. I just came to say good-bye, really.”

Tilly’s eyes filled with tears. “Why?” she said.

“You’ll be all right now,” Helen said. “You don’t need me any longer.”

“What do you mean?”

But Helen didn’t answer. She hugged Tilly tight for a second. “I’m glad we saw the cubs, even though it was for such a short time. Perhaps you’ll see them when they’re bigger. They’ll come back to the garden to play and hunt, I expect.”

Tilly crawled out of the den. “I still don’t understand. Why do you have to go? Please explain…Where are you going?”

Helen was already running, fast and light, toward the trees.

Tilly watched her, dazed. She didn’t even try to follow. The snow seemed to glow, bright as daytime. She looked up at the sky. The snow was coming down thicker and faster now. Huge, soft feathers, swirling and dancing and spinning down to earth.

When she looked for her again, the girl had vanished. Not a trace remained: her footsteps had already been completely covered up by snow. It was as if she had never even been there in the first place.